Until the 1970s, even as the territory system grew, all of professional wrestling seemed to share in successes and failures. When wrestling had its booms and busts during the Great Depression, or its mainstream boom in the 1950s, or its decline in the 1960s, it was up or down everywhere. The 1970s was the introduction of an uneven landscape that remains today. There were now winners and losers.

In 1974, Dusty Rhodes turned babyface, which led to an amazing and extended period of success for the Florida territory. Georgia and the Carolinas remained pretty consistent and strong for most of the 1970s as well. The Japanese scene was continuing to grow. Baba and Inoki were not stars on the level of Rikidozan, just as the next wave of stars weren’t at the level of Baba and Inoki, but wrestling was still healthy. The WWWF remained very strong, powered by the stardom of Bruno Sammartino, the championship reign of Pedro Morales, TV in the New York market and a lock on Madison Square Garden, the most prestigious arena in America. By 1974, they also had Andre the Giant as a top featured attraction and were able to book him on tours around the world.

In other cases, the decade started off strong and faded as the years progressed. That was true for the AWA, California and Detroit. Stampede, which almost closed its doors for good, needed a full scale reinvention when the old way of doing business stopped working, and found purpose rebuilding around smaller and more athletic wrestlers.

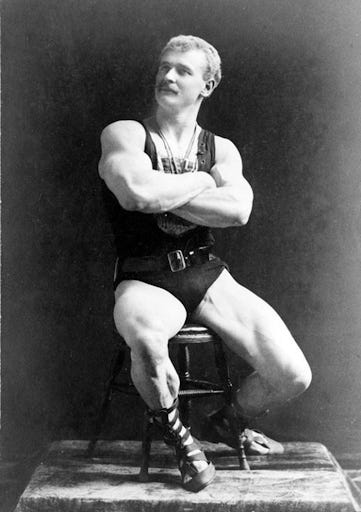

If the change in the in-ring style in Stampede predicted the long-term future of pro wrestling, the shifts happening elsewhere predicted the immediate decade ahead. Jack Brisco, an NWA World Champion and major star in the mid-1970s, was heavily influenced by great “pure” wrestlers like Lou Thesz and Danny Hodge, but would eventually seem passe when colorful, muscular characters like Superstar Graham, who copied the interview style of Muhammad Ali, became a major star. The change was less a flip of a switch and more of a gradual move. Bob Backlund, a square personality but talented pro wrestler very much in the mold of Jack Brisco, became the WWWF World Champion in 1978 and was accepted by fans at the beginning, but soundly rejected by the end of his run on top.

In 1972, an Atlanta businessman named Ted Turner started a UHF station called WTCG where he featured professional wrestling in a 6:00 time slot on Saturday nights, which was the first show to really do notable ratings. (When he expanded the show to two hours, the ratings increased even more.) Within four years, Turner put the station on satellite, which made it the first SuperStation and led to Georgia Championship Wrestling being available in many markets nationwide. Likewise, in 1973, a premium television network called HBO (short for Home Box Office) started broadcasting a show called World Championship Boxing, which hinted at a future for pro wrestling on pay-per-view. Wrestling was showing early signs of change. While most territories were insulated from the impact of cable TV at first, this meant that some fans would be able to not just read about what was happening in magazines, but possibly even see wrestling in other places.

Let’s say that a booker lays out an angle in the Mid-Atlantic area, then becomes a booker in Florida and lays out a similar angle in Miami a year later. It might even feature at least one of the same players. Are fans who saw both versions of the angle to think they only witnessed coincidence? In addition, fans who grew up in parts of the country with subpar performers who headlined shows in bad matches were now exposed to great wrestling happening elsewhere. These types of revelations couldn’t help but erode the mystique of the home promotion, and in some ways professional wrestling as a whole. Slowly but surely, wrestling fans who could at least play along with the idea that they were fans of real sport found it more challenging to suspend their disbelief. Sensing that wrestling was changing, Dory and Terry Funk decided to close the Amarillo territory in 1975, believing that the rise of cable television would render their business model obsolete.

By the end of the decade, a new form of technology called a Video Cassette Recorder, or VCR, started to become a household institution. This device allowed users to record shows from television to watch again later. The most devoted wrestling fans in the world seized on this new technology and started taping wrestling, not just for themselves, but to trade with other fans in part of the country. In previous times, hardcore fans who wanted to stay up to date on happenings around the country could only subscribe to wrestling magazines or fan-made newsletters. With the advent of the VCR, those newsletters were often accompanied by a videotape of local wrestling.

In some ways, these fans were more forward-thinking than the promoters who aired the wrestling were, as most promoters simply taped over old episodes to save money. To this day, so much wrestling footage only exists because a wrestling fan somewhere preserved it. We start seeing hints of this trend in the late 70s, and by the early 80s, it was common practice — not just nationally, but internationally. Soon, wrestling fans, including those who had aspirations of becoming professional wrestlers, would have a way they could view wrestling from around the world, which would prove itself a game changer, as we’ll see in the 1980s.