-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

Osamu Abe (阿部脩) Profession: Wrestler, Referee Real name: Osamu Abe Professional names: not applicable Life: 5/6/1925-early 1980s Born: Asahikawa, Hokkaido, Japan Career: 1954-1958, 1966-1977 (as referee) Height/Weight: 172cm/100kg (5’8”/220lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Long after an unremarkable stint with the JWA, Osamu Abe returned to the business to become the IWE's head referee for most of its existence. Hokkaido native Osamu Abe played baseball in junior high, then entered sumo for an unspecified stable from 1940 to 1946. Under the shikona Onaruyama, he peaked in 1944 when he reached the makushita division but had been knocked back down to sandanme by the last tournament of the Pacific War in June 1945. Eight years after his retirement, Abe joined the Japan Wrestling Association, debuting on their August 1954 tour. In late 1955, Abe reached the finals of a qualifying tournament for the Japanese Junior Heavyweight title, where he lost to Surugaumi. Abe left in 1958, during the lowest point of the Rikidozan era, to become a contracted actor with Daiei. His resume ranged from childrens’ television to Gamera films. At some point, Abe made headlines for his marriage to a Takarazuka Revue actress. In 1961, Abe came out of retirement to join Surugaumi and Takao Kaneko for a pair of shows in Seoul. Five years later, Abe was recruited for Tokyo Pro Wrestling as a referee and remained with the company through its merger with the International Wrestling Enterprise. Abe became Kokusai’s head referee and maintained the position for most of its lifetime. In keeping with the company's product, this saw him take plenty of bumps for the foreign heels of the month. He also promoted the company’s shows in Hokkaido, and in a final flourish in the summer of 1977, promoted twelve shows across the island with a mobile tent he had purchased himself. After an unsuccessful run for a seat on the House of Councilors that year, Abe did not return to the IWE. According to Mighty Inoue in a 2016 interview with the fanzine Showa Puroresu, Abe opened a restaurant named after Rikidozan in Fukuoka in the early 1980s. Inoue further disclosed that Abe died of a stroke around that time, which Osamu himself had predicted due to a family history.

-

- jwa

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

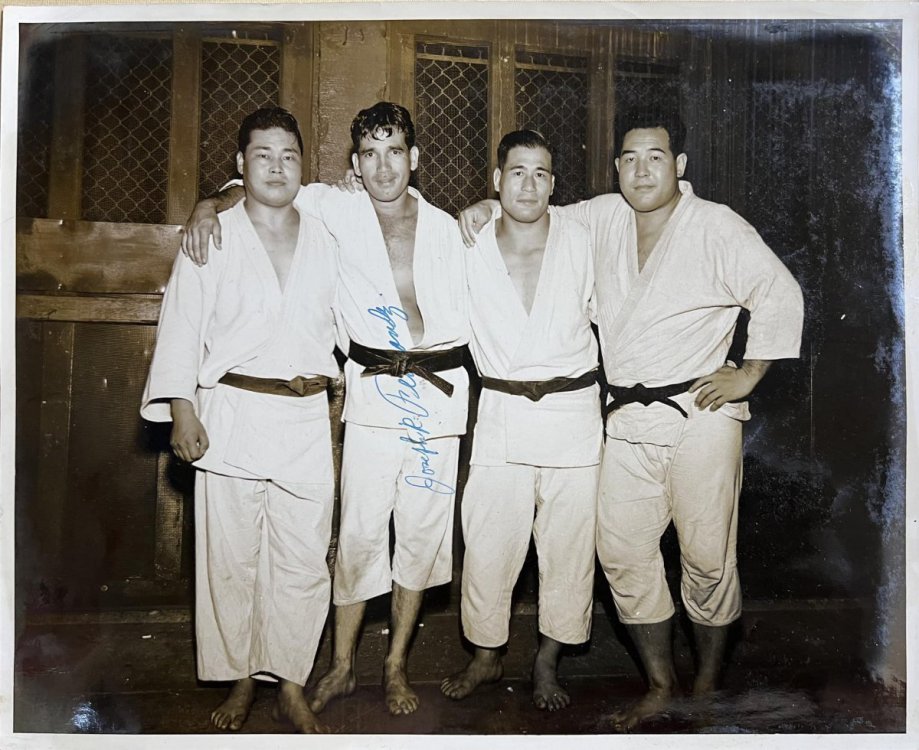

Takao Kaneko (金子武雄) Profession: Wrestler, Referee Real name: Takao Kaneko Professional names: not applicable Life: 1/15/1930-unknown Born: Kanagawa, Japan Career: 1954-1961, 1968 (as referee) Height/Weight: 172cm/100kg (5’8”/220lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Puroresu’s first “macho wrestler”, Takao Kaneko worked for the JWA throughout the 1950s before opening his own gym. The first generation of puroresu was made up of various sportsmen who transferred their skills into pro wrestling. Takao Kaneko was unique among these in that he did not compete in a combat sport; no, the 24-year-old from Kanagawa was a weightlifter. The light heavyweight champion debuted for the JWA in August 1954, as puroresu’s first “macho wrestler”. However good his body may have looked, though, he could only go so far with his frame. Kaneko participated in the 1956 Japan Light Heavyweight tournament, held to delegitimize and scout the JWA’s competition. In the second match, Kanji Higuchi allegedly injured Kaneko with a shoot arm lock to win. However, Kaneko continued to work for the company through February 1961. That April, Kaneko held a pair of shows in Seoul with Surugaumi, Osamu Abe, and some American soldiers. This was shortly before Jang Yeong-chol and Chun Kyu-deok began to run shows there themselves. Kaneko would then open the Sky Bodybuilding Gym in Yokohama. As a good friend of Isao Yoshiwara, Kaneko would not only refer his clients (Tenshin Yonemura, Masahiko Takasugi) to join the IWE, but also worked as a referee for around a year circa 1968. Other wrestlers associated with the Sky gym include Yoshiaki Fujiwara and Minoru Suzuki.

-

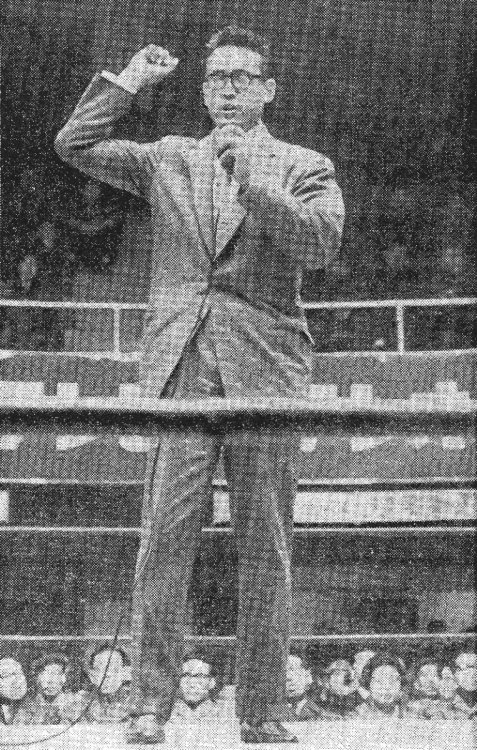

Tamio Takeshita (竹下民夫) Profession: Wrestler, Referee, Announcer Real name: Tamio Takeshita Professional names: Iwao Takeshita, Tamio Takeshita Life: 12/29/1938-unknown Born: Fusamoto (now Otaki), Chiba, Japan Career: 1960-1961, 1966-1977 Height/Weight: 175cm/85kg (5’9”/187lbs.) Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, International Wrestling Enterprise Puroresu’s first pro-baseball transplant, Tamio Takeshita had a far humbler career than the man he encouraged to do the same. Born in the Chiba village of Fusamoto—which became part of modern-day Otaki when he was fifteen—Tamio Takeshita played baseball in upper elementary and junior high. He intended to play at Otaki High, and passed the school’s entrance exam, but was scouted for sumo by a local horse trader. This bakuro introduced Tamio to the Nishonoseki stable. Takeshita wrestled for two years and earned the shikona Fusanoumi. In late 1957, though, he ran away with a senior who had just gotten a tryout with the Daiei Unions. Hattori-san (who wrestled as Takasakiyama) failed that tryout but made it onto the minor-league “second squad” of the Yomiuri Giants, where he played for two years. Takeshita passed a tryout for the JNR Swallows (now Yakult). The left-handed pitcher played on the second squad, but there was no hope of promotion: not when the A-team featured the greatest pitcher in NPB history, Masaichi Kaneda. Tamio himself later admitted that he was a better batter, but even the Swallows’ B-team was saturated with quality players. He was cut in spring 1959, and no other teams were interested. That fall, Takeshita visited former sumo senior Junzo Yoshinosato at the JWA’s offices in Tokyo. When Rikidozan learned of Tamio’s baseball stint, he gave him “a simple test”, and brought him into pro wrestling. Takeshita debuted in February 1960, on the undercard of a TV taping at the Naniwacho Gymnasium. He lost to Kiyotaka Otsubo in just over five minutes. One day in March, former Yomiuri Giants pitcher Shohei Baba visited the Japan Pro Wrestling Center in Nihonbashi, hoping to meet Rikidozan (who was overseas in Brazil at the time). It was Takeshita who suggested that Baba follow his example and pivot into pro wrestling, and Shohei would meet with Rikidozan the following month with intent on doing just that. Takeshita left the company around eighteen months later. He had suffered a head injury in a Tottori match against Mammoth Suzuki and had been on the bench for a month when his mother “collapsed”. He spent two years caring for her. Tamio rejoined the JWA in early 1964. However, the company had decided not to accept new wrestlers after Rikidozan's death, so Takeshita worked as a driver. His requests to return to the ring were brushed aside, and when Toyonobori left to form Tokyo Pro Wrestling in 1966, Tamio followed him. Tokyo Pro held its kickoff show at the Kuramae Kokugikan that October. With the new ring name Iwao Takeshita, Tamio won his first match in five years against the debuting Isamu Teranishi. When the company merged with the International Wrestling Enterprise, Takeshita reverted to his real name, and wrestled for Kokusai through late 1968, while pulling double duty as a referee. He became the company's announcer in 1970, but also worked in the sales department. (During one tour in autumn 1974, Takeshita was so busy with sales that, on some dates, the sales representative in charge of the show had to fill in as announcer.) Tamio got married in the spring of 1972, and as of 1979, he and Kyoko had two children. He retired in 1977, and was replaced by fellow salesman Toshio Suzuki, and then general employee Kazutoshi Iibachi.

- 1 reply

-

- jwa

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

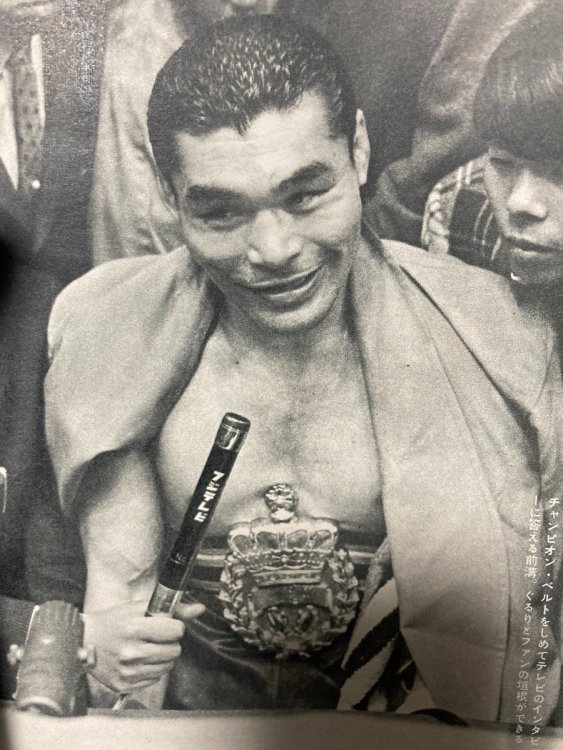

Takao Maemizo (前溝隆男) Profession: Referee Real name: Takao Maemizo Professional names: not applicable Life: 8/??/1937- Born: Tonga Career: 197?-1979 Height/Weight: unknown Signature moves: unknown Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none After an athletic career across multiple sports, Takao Maemizo worked as a referee for the IWE. Maemizo during his second middleweight title reign, circa spring 1964. Takao Maemizo was the illegitimate child of a Japanese businessman, born to a Tongan mother while his father was posted there for his trading company. He returned to Japan with his father and was raised as part of his family at home, but after graduating junior high, Maemizo moved to Tokyo and entered sumo in 1952. As a member of the Mihogaseki stable, Takao wrestled as Masunishiki in a five-year career. Allegedly bullied by patrons for his curly hair, Maemizo quit sumo after the first tournament of 1957, and attempted a pivot into professional baseball. He actually passed a tryout with the Daiei Unions, the 1957 merger of the Takahashi Unions and Daiei Stars, but the team closed after one season and Maemizo received no more offers. In autumn 1958, Maemizo debuted as a professional boxer. Besides a handful of fights in Seoul, Brisbane, and Manila, his career was mostly spent at home, where he enjoyed two reigns with the Japan Boxing Commission’s middleweight title in 1962 and 1963. After a final victory in January 1966 against late-career rival Morio Kaneda, Maemizo switched sports yet again to professional bowling. Finally, he joined the International Wrestling Enterprise as a referee. While Maemizo was the promotion’s head referee for a time, after Osamu Abe left in 1977 to unsuccessfully run for public office, he was displaced by noted bodybuilder Mitsuo Endo, and left in 1979 to join Umeyuki Kiyomigawa’s ill-fated joshi promotion New World Women’s Pro Wrestling. That, as far as I know, was the end of Maemizo’s career in sport.

-

Daigoro Ogiyama (扇山大五郎) Profession: Wrestler Real name: Tamio Takahashi (高橋民雄) Professional names: Daigoro Ogiyama Life: 3/27/1938- Born: Kurihara, Miyagi, Japan Career: 1969-1970 Height/Weight: 178cm/105kg (5’10”/231lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Former rikishi Daigoro Ogiyama wrestled a short stint for the IWE. Tamio Takahashi was a teenage baker scouted for sumo. From his debut in 1955, he wrestled for the Tokitsukaze stable for thirteen years. Takahashi, who would take on the shikona of Ogiyama (with various first names) in 1957, was a smaller rikishi who compensated for his frame with agility and technical skill and was particularly noted for his left-hand upper throws and komata-sukui (leg-scooping throws). A narrow defeat in the January 1958 tournament’s sandanme division earned him a promotion to makushita. Three years later, Ogiyama won that division in the last tournament of 1961, and was promoted to juryo. Most of the rest of his career was spent in this division, although he clawed his way up to the top makuuchi division for nearly a year starting in autumn 1962. He would reach that rank two more times in his career. However, as Ogiyama reached his thirties, he fell back down to makushita, and would retire in the fall of 1968. Ogiyama was managing a Chinese restaurant when he was scouted by Toyonobori in early 1969. While Ogiyama was hardly the first man with a sumo history to join the International Wrestling Enterprise, no new recruit had had nearly as much experience as him. Perhaps that mileage on his body was his downfall, as Ogiyama would barely spend a year with the company. His recruitment did garner some attention, and his name was considered for a European excursion, but Ogiyama retired in early 1970. The timing suggests that it may have been connected to Toyonobori’s own retirement. As Mighty Inoue recalled in a 2016 interview with the Showa Puroresu fanzine, Ogiyama was a gentle and kind man, albeit with a weak temperament and a love of gambling, and not a very good wrestler.

-

Asataro Sano (佐野浅太郎) Profession: Wrestler Real name: Minoru Sano (佐野実) Professional names: Minoru Sano, Asataro Sano, Tohachi Sano, Senpu Sano Life: 3/30/1948- Born: Kurita, Shiga, Japan Career: 1968-1971 Height/Weight: 186cm/90kg (6’1”/198lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Asataro Sano was an early sumo transfer in the IWE. Asataro Sano joined the Asahiyama sumo stable after graduating from Seta Technical High School and debuted in May 1965. He would not truly enter until the last tournament of the year that November, and despite adopting the shikona of Hiyoshiyama in spring 1966, Sano was simply unable to gain enough weight to effectively compete, and he only made mediocre showings before he retired in early 1967. In February 1968, Sano joined the International Wrestling Enterprise, during their brief rebrand as TBS Pro Wrestling. Assigned as a valet to Toyonobori (and later, to Thunder Sugiyama), Sano trained and debuted in May with a loss to Takeshi Oiso. Sano was a good jumper with a great dropkick, and several people saw potential in him. IWE booker Umeyuki Kiyomigawa considered him a candidate at one point for a French excursion, and foreign ace Billy Robinson regarded him as a potential star. Sadly, a serious injury forced Sano into retirement in the early 1970s. On June 27, 1970, a kick from Isamu Teranishi not only broke one of his ribs but caused it to rupture a lung. He made two attempts to return in 1971. In January, a match against Devil Murasaki aggravated his lung and he was put on the shelf. His final dates for the company came that July, when a match against Gerard Etifier (Jiro Inazuma/Gerry Morrow) in Miyagi went to a doctor stoppage. Despite an alleged offer from Giant Baba to join AJPW, Sano would never wrestle again.

-

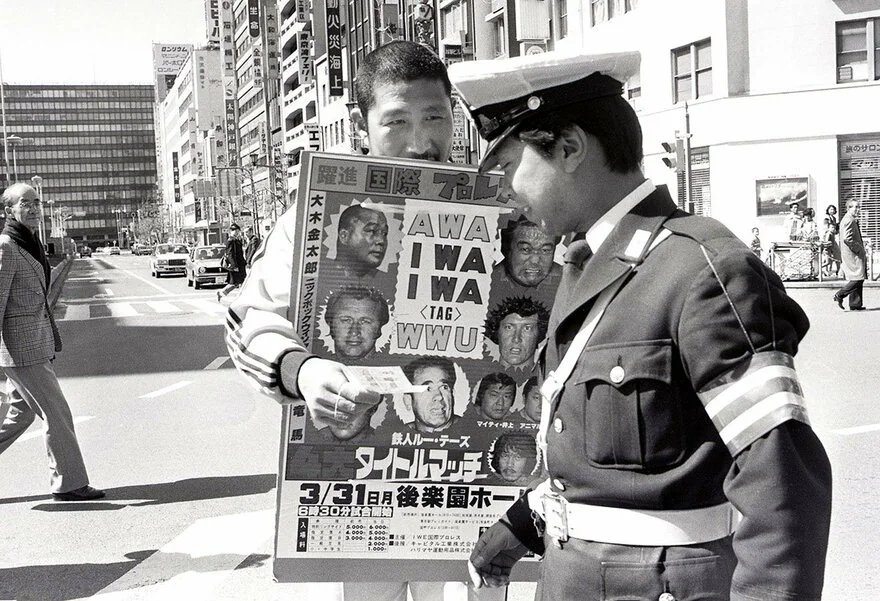

Shogun KY Wakamatsu (将軍KYワカマツ) Profession: Wrestler, Manager, Promoter Real name: Ichimasa Wakamatsu (若松市政) Professional names: Ichimasa Wakamatsu, KY Wakamatsu, Shogun KY Wakamatsu Life: 1942/01/01- Born: Hakodate, Hokkaido, Japan Career: 1973- Height/Weight: 181cm/105kg (5’11”/231 lbs.) Signature moves: KY Special (abdominal stretch) Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise, New Japan Pro-Wrestling, SWS, Pro Wrestling Crusaders, Dosanko Pro Wrestling Dojo Geki (as promoter) Titles: none A thirty-year-old roadie who trained to wrestle for the IWE, Shogun KY Wakamatsu found his greatest success as a heel manager in the 1980s. Wakamatsu tries to sell an IWE ticket to a Tokyo traffic cop on March 23, 1980. After graduating junior high, Ichimasa Wakamatsu had spent fifteen years working as an electrician and stevedore before he joined the International Wrestling Enterprise. His primary job was and would remain as a member of the ring crew, but he trained to wrestle part-time, filling up the company’s undercards as a second-string wrestler. He debuted on September 29, 1973, in a singles match against Katsuzo Oiyama. Judging by Cagematch records, he worked roughly 20 to 35 dates per year for the rest of the decade, as he left his family in Hokkaido to live alone in the IWE’s Omiya dojo. On September 13, 1976, Wakamatsu made national news when he drove the IWE truck by a family whose house was caught in a landslide. He stopped and helped them gather their belongings as, unbeknownst to him, an NHK news crew broadcast his efforts live. On August 26, 1979, he entered the Pro Wrestling Dream All-Star Match show’s opening battle royal, in which his future client Junji Hirata also competed. By that time, he was sharing his truck rides with Hiromichi Fuyuki, a ring crew employee who pivoted into his own wrestling career. Wakamatsu was scheduled to go overseas in the summer of 1980, after a last match against Nobuyoshi Sugawara. This instead ended up being his last match for several years, as Wakamatsu refused to leave the company in its most vulnerable state. He pivoted into sales work to help keep Kokusai afloat. After their last tour with full network backing, Wakamatsu was hospitalized for pancreatitis, but he was soon putting up posters for the next tour. IWE television producer Motokazu Tanaka has stated that Wakamatsu is “one-third” of the reason that the company survived as long as it did during its death rattle. His Japanese Wikipedia page claims that he could not return to Hokkaido after the company went under because he had received a parting gift from the supporters’ association in Ashibetsu. Whatever that means, he returned to electrical work, punching the clock for TEPCO until he had enough money to travel to Calgary. Wakamatsu began work for Stampede Wrestling in 1982. Stu Hart gave him the ring name KY Wakamatsu, in reference to an unspecified Canadian general. (I would appreciate it if any Canadians could explain the reference, as I could not find a name with those initials.) While he would wrestle for Stampede, his most notable work was managerial, as Wakamatsu offered his services to Bad News Allen. KY played a part in Allen’s 1983 feud with the Dynamite Kid, and was part of the mix late that year, when a Bruce Hart angle in which Allen broke the neck of the Stomper’s kayfabe son derailed Stampede. Wakamatsu returns to Japan in August 1984. Junji Hirata, who had worked in Stampede as Sonny Two Rivers, was called back to New Japan in the summer of 1984. As he was told, the plan was to license a Kinnikuman gimmick, in an attempt to replicate the success of Tiger Mask after the Cobra had not caught fire. Wakamatsu was invited to join NJPW by his old boss, Isao Yoshiwara, who had taken a consulting position with the company. Due to the Kinnikuman anime being broadcast on AJPW’s Nippon TV, negotiations proved difficult, and were still underway when Hirata and Wakamatsu made their first appearance on World Pro Wrestling. Hirata wore shoulder pads under a white t-shirt, and a blue balaclava over his Kinnikuman mask, while Wakamatsu wore a bowler hat, surgical gown, and Geordi La Forge-esque visor, while also donning a whip. One week after this first appearance, amidst Naoki Otsuka’s announcement that he would pull wrestlers out of NJPW, the two appeared again at a Minami-Ashigara show. This time, Hirata had selected a new mask inspired by the manga Laughing Mask. As Wakamatsu claimed in a 2016 G Spirits interview, he improvised his client’s new ring name on the spot: Strong Machine. A singles match with Inoki was set for September 7, and on that day, the gimmick kicked into second gear. Wakamatsu recalled in G Spirits that he had been inspired by the Assassins, the Jody Hamilton tag team, to create “an army” of wrestlers with the same masks and costumes. For his official debut, “Strong Machine #1” was seconded by Wakamatsu and thirded by Strong Machine #2 (Korean wrestler Yang Seung-hee). Phil Lafon played a third Strong Machine for a single November appearance, but skipped out on wrestling due to a cold, which led a maskless Hiro Saito to take his place. In January 1985, the Machine Army reached its full form, as NJPW’s connections to Polynesian Pacific Wrestling saw them book the original IWE trainee turned overseas journeyman Yasu Fujii, and Ratou Atisano’e, the younger brother of Samoan rikishi Konishiki Yasokichi, as #3 and #4 respectively. (Atisano’e had no wrestling experience, but hardly wrestled anyway.) By then, Wakamatsu had developed his costume. He had switched out the visor for sunglasses, and the surgical attire for black and red outfits, which read KAERE (“Get out!”) on the back. As the gimmick was that these wrestlers were under Wakamatsu’s direct control (which led play-by-play man Ichiro Furutachi to throw out nicknames like “the Dr. Ochanomizu of Hell” and “Evil Shotaro-kun”), he used a red megaphone to shout orders to them while also talking to the audience. This predated Jimmy Hart, and as has been alleged, may have inspired him. Wakamatsu with Bill Eadle and Andre the Giant in August 1985. The Machine Corps angle kept New Japan afloat after the devastating pullout of Riki Choshu and Ishin Gundan, as World Pro Wrestling ratings did decline, but remained over 15%. However, NJPW saw the gimmick as a time-filler, and when Bruiser Brody was swiped from All Japan the following spring, the Machine Army suffered. In an April singles match against Tatsumi Fujinami, Strong Machine #1 was accidentally blinded by Wakamatsu’s powder attack and lost to a Dragon Suplex. This led Hirata to split from the Army and become Super Strong Machine, and disagreements with an office that wanted him to unmask and return to the company’s main unit—which infamously manifested in a Fujinami promo where he broke kayfabe and called Hirata by his real name—eventually led Hirata to leave New Japan. While the Strong Machines soldiered on without SSM for a few months, and Wakamatsu released a novelty single in the meantime, Hirata’s August departure led to their disbandment. In a desperate, last-minute measure, Andre the Giant was given a Machine mask to wrestle as Wakamatsu’s new client, Giant Machine. Even if his bare face had not already been advertised on tour posters, the Giant Machine’s identity would have been obvious. But it meant more work for Wakamatsu, as Bill Eadle also donned a Machine mask. When the WWF ran their own version of the Machines gimmick, Andre even offered to get Wakamatsu work overseas. However, he was under contract with TV Asahi, and refused out of loyalty to the late Yoshiwara and TV Asahi executive Takahei Nagasato. On May 1, 1986, during Andre’s final NJPW tour (where they didn’t bother with the Machine gimmick), Wakamatsu wrestled his first match since Stampede, teaming with the Giant against Antonio Inoki and Umanosuke Ueda in a Ryogoku Kokugikan main event; he took the pinfall in eight minutes after receiving an Inoki enzuigiri. The heel manager remained in rotation through 1986, with clientele ranging from Kendo Nagasaki and Mr. Pogo, to Madd Maxx and Super Maxx, to Konga the Barbarian and “Super Mario Man” (Ray Candy in a white mask). In the late 1980s, Wakamatsu became acquainted with Megane Super eyewear magnate Hachiro Tanaka, and the two watched Newborn UWF shows together. As the decade came to a close, Tanaka prepared to enter the wrestling business himself, and Wakamatsu was one of his closest allies. In the summer of 1989, Wakamatsu traveled to Calgary to work a handful of dates for the dying Stampede, and to attempt to secure the support of Mr. Hito. After this, he made stops across the United States, where he worked with the USWA in Texas, and helped Kazuo Sakurada attempt (nearly successfully) to court Keiji Mutoh towards signing with Tanaka’s new company when he finished his WCW excursion as the Great Muta. After a stop in Germany, he returned home in November. Wakamatsu continued to recruit talent as SWS took shape. He was responsible for signing the biggest ex-NJPW star that the company would feature, George Takano. (According to an uncited passage on Japanese Wikipedia, Wakamatsu had intended to sign his brother Shunji instead, and had asked George for his contact details, but George lied and claimed that he did not speak much with Shunji in order to get himself a better position in the company.) Wakamatsu officially joined SWS in May 1990. In the promotion’s sumo-inspired room system, he was made the leader of the Dojo Geki stable. He wrestled on the company’s second-ever show, beating Fumihiro Niikura in the third match. Although the following year saw Wakamatsu work a handful of tag matches, he left the company after the death of his wife, with Yoshiaki Yatsu taking his place as Dojo Geki head. Wakamatsu and Super Strong Machine reunite for the latter's 2019 retirement ceremony. Wakamatsu returned to wrestling in 1993, working with Shunji Takano’s Pro Wrestling Crusaders promotion as the leader of the Space Power Corps. In keeping with PWC’s wackier tendencies, he used supernatural abilities such as telekinesis in the ring, and once even made an opponent faint through his “great cosmic power”. In 1994, Wakamatsu formed a small promotion in his native Hokkaido, Dosanko Pro Wrestling Dojo Geki. In 1999, he transitioned into local politics when he was elected to the Ashibetsu City council. Outside of a couple appearances in FMW and DDT at the start of the new millennium, Wakamatsu apparently stepped back from significant wrestling work until a tag team battle royal at a 2007 independent show in Tokyo, which he won alongside Great Kojika. In the 2010s and beyond, he has made appearances for shows promoted by the Hokkaido indies Hokuto Pro Wrestling and Asian Pro Wrestling, as well as a couple of Shonan Pro Wrestling shows promoted by former IWE coworker Masahiko Takasugi, and Keiji Mutoh’s 2019 Pro-Wrestling Masters show. At the time of his matches in September 2023, Wakamatsu was the eldest active wrestler in Japan.

-

Mr. Hayashi (ミスター林) Profession: Wrestler, Referee Real name: Koichi Hayashi (林幸一) Professional names: Koichi Hayashi, Ushinosuke Hayashi, Tor Hayashi, Taru Hayashi, Mr. Hayashi Life: 5/17/1942-11/4/1999 Born: Koto, Tokyo, Japan Career: 1959-1991(?) Height/Weight: 176cm/98kg (5’9”/216lbs.) Signature moves: Karate chop, neckbreaker Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, All Japan Pro Wrestling, Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling (as referee) Titles: none After a lengthy but unremarkable career as an undercard wrestler, Mr. Hayashi made a noted transition into refereeing. An only child raised by a single mother in eastern Tokyo, Koichi Hayashi entered sumo in 1958. First joining the Oitekaze stable, he left to join the spinoff Magaki stable upon its formation the following February but then retired to join the Japan Wrestling Association in November 1959. The following year, Hayashi invited his former stablemate Hiroshi Ueda to join him. Hayashi’s earliest-known match is a June 9, 1960 loss against Kiyotaka Otsubo; an inauspicious start for a frankly inconspicuous career as a wrestler. Hayashi entered a tournament just three months after his debut to determine the JWA’s light heavyweight champion, after Junzo Yoshinosato had received Michiaki Yoshimura’s junior title, but in the first round on September 30—the same day Shohei Baba and Kanji Inoki made their debuts—Hayashi lost to tournament winner Isao Yoshiwara. Anecdotes on Hayashi from this period remark on a penchant for oversleeping and disdain for training, but interestingly, they also suggest that he saw Rikidozan as a father figure. By 1963, Hayashi had adopted the ring name that would follow him for the rest of his JWA tenure: Ushinosuke Hayashi. Anybody familiar with puroresu of the time will know that such a ring name would have only been bestowed upon him by Toyonobori. In fact, Hayashi became part of Toyonobori’s posse, the Hayabusa Corps, in the post-Rikidozan era. At some point, he also became Yoshinosato’s chauffeur. Hayashi would wrestle for the JWA through the end of 1972, when he was part of the last crop of talent sent overseas by the dying promotion. Six months before his AJPW debut, Hayashi meets with Jumbo Tsuruta, Mitsuo Hata, and Yoshihiro Momota in Florida. For the next three years, Hayashi wrestled overseas. First, in EMLL, he wrestled alongside Kantaro Hoshino (as Yamamoto), and his excursion even began with a program against the NWA Light Heavyweight champion, Ray Mendoza. While Hoshino returned to Japan to join NJPW that autumn, Hayashi just went north. From 1974 through mid-1976, he wrestled across the southeastern United States, mostly for CWF, GCW, and Mid-Atlantic. He appears to have returned to Japan in late 1975, as a gap in Cagematch records is backed up with a contemporaneous Gong interview with Isao Yoshiwara. I do not know whether Hayashi had sought a job with Yoshiwara’s IWE, as he may have just been in the fold due to his association with Yoshinosato (who was then working for the company as a color commentator), but by the following year, he was back Stateside. In February, he was photographed in Florida with Jumbo Tsuruta. Just a few months after that photo saw print in Monthly Pro Wrestling, Hayashi debuted for All Japan Pro Wrestling on the Black Power Series in August 1976. Hayashi counts a pinfall for a young Mayumi Ozaki. After Mitsu Hirai’s retirement in 1978, Hayashi became the seniormost wrestler in the company; by the end of his career, he was the seniormost active wrestler in Japan. No footage of his work survives, but it reportedly had some comedic elements. Hayashi even wrestled in pink trunks, predating Haruka Eigen by a decade. He participated in the opening battle royal of the 1979 Pro Wrestling All-Star Dream Match show. Shortly before the end of the 1982 Excite Series tour, on a house show in Akita, Hayashi injured his left knee and ankle during a match against Mitsuo Momota. He would never wrestle again. Two days later in Nagaoka, he debuted as a referee, and had officially begun in that capacity fulltime by the start of the following tour. In most of the time since Jerry Murdock’s 1976 firing, Joe Higuchi and Kyohei Wada had been AJPW’s only referees. Hayashi would overtake Wada in the hierarchy, making regular appearances on television. (Unbeknownst to Baba, Hayashi would supplement his income with part-time janitorial work at a theme park.) On the final show of 1983, under the last two matches in that year’s Real World Tag League, Hayashi officiated Ric Flair’s NWA World Heavyweight title defense against the Great Kabuki. In the early years of Weekly Pro Wrestling, Hayashi also wrote a column in which he reminisced on his JWA days. According to an April 1988 article in that magazine, Hayashi may have borne some responsibility for Baba’s decision to send Tarzan Goto on excursion in 1985. Goto had complained about Hayashi eating his food in the dojo refrigerator, and had vowed that, if he became head of the dojo, he would get Hayashi fired. Hayashi then turned to Baba and claimed that Goto, in fact, had been eating the food, framing his junior to save his job. When that fiscal year ended the following spring, though, Hayashi himself would be laid off, alongside wrestlers Ryuma Go, Apollo Sugawara, and Masahiko Takasugi. Much as the acquisition of the Calgary Hurricanes made those three redundant, Hayashi’s place as second referee had been taken by Tiger Hattori. Unlike the Kokusai Ketsumeigun trio, he at least received a respectful sendoff through a retirement ceremony at AJPW’s April 1 show. Hayashi found continued work as a referee with Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling when it opened that summer, but I do not know if he stayed with the company through its dissolution, only that he did not work for either of its splinter promotions. (Cagematch claims that Hayashi worked until 1998, but it erroneously states that he worked for AJW, not JWP, so I do not trust it.) He died of a heart attack in 1999.

-

MAJOR UPDATE: I have corrected some glaring errors and significantly expanded this profile with info on Sugiyama's early life and IWA world title victory.

-

I have begun the successor to these threads: my own Tsuruta biography. JUMBO! [01]: Mountains of Kai – From Milo To Misawa (wordpress.com)

-

I never got around to mentioning this in the piece itself, so I am doing so in a follow-up comment. There could have been another All-Star show in 1982, to build upon the truce that the companies called after the previous year's "pullout war". NJPW was surging ahead of its competition by this point, but they needed cash; Anton Hi-Cel was not cheap. Inoki asked Motoyama for a deposit, and sure enough, he immediately cashed the 300-million-yen check that Tokyo Sports wrote out. However, Baba did not cash his check, as he was reluctant to trust Inoki again. The guy that ToSpo put in charge of managing this show ultimately called Ryozo Yonezawa, saying that he had already given Baba the money and imploring him to reach out as soon as possible. This broke Baba's condition for absolute secrecy, and he returned the check.

- 1 reply

-

- ajpw history

- njpw history

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Oh right, I forgot about Rolling Dreamer! That was produced in 1979, but they didn't start using the instrumental version as his theme until 1980.

-

La Bestia Magnifica ("The Magnificent Beast") 1953 Películas Nacionales Directed by Chano Urueta, a pioneer of both Mexican horror and lucha cinema, La Bestia magnifica started the wrestling feature film in Mexico. Starring actor-luchadores Crox Alvarado and Wolf Ruvinskis (the future Neutrón) alongside actress Miroslava Stern, the movie contained three full matches. These involved lucha legends such as Enrique Llanes and Rito Romero. A print of the film found its way to South Korea as early as 1957. Half a decade later, its wrestling scenes were studied by Korean wrestling pioneers Jang Yeong-chol and Chun Kyu-deok. A 1957 issue of Korean magazine Screen advertises the film.

-

Here's Bob talking about wrestling on Minneapolis public access TV in 1999.

-

What makes a lot of early puroresu entrance music so novel is that it was often material that 70s television networks were licensing to use anyway, not just for wrestling. Specific commissions were rare; off the top of my head, Inoki, Sakaguchi, Fujinami, the Funks, and Ashura Hara were the only ones in the 70s. (And I'm not 100% sure about the Funks! That could be a Sunrise situation, where the song already existed.) "Sky High" had a string arrangement by Richard Hewson. Billy Robinson's "Blue Eyed Soul" was a Hewson arrangement. Dick Murdoch's AJPW theme, "Love Bite", was directly credited to The Richard Hewson Orchestra. Later on, you have smooth jazz fusion saxophonist Tom Scott providing music for the British Bulldogs as well as Akio Sato & Takashi Ishikawa's tag team. Meanwhile, you had NJPW's love of disco-era Maynard Ferguson. Hogan came out to his "Battlestar Galactica", Masked Superstar had "The Fly" from Conquistador, and Ryuma Go used his cover of EW&F's "Fantasy" on at least one occasion. (Not wrestling, but Nippon TV used Ferguson's Star Trek theme cover for one of their most famous game shows, Trans America Ultra Quiz. See what I mean about production music?) Unrelated, but I want to buy a drink for whoever on TV Asahi's production staff decided to license the Waterboys for Billy Jack Haynes in 1985.

-

It's "Zero To Sixty In Five" by Pablo Cruise. At least that's what they actually came out to, couldn't tell you what they dubbed over on the DVD releases.

-

Pompeii Deathmatch over whether Roger gets to post on Pink Floyd's social media accounts, which everyone knows he will use to promote the 40th anniversary remix of The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking. You've got thematic props for the big albums, but I would book the Amphitheatre for sheer atmosphere. Ring in the center, with a replica of the band’s Pompeii stage set in front. 15-foot Wall in one corner, for someone to dive off of at one point. The brawl spills into catering, and Dave bumps onto Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast. He does not, however, bump onto Rick’s organ despite repeated teases, out of respect. It turns out to Dave's horror that, with quiet reflection and great dedication, Roger has mastered the art of karate! But Polly interferes and hits a low blow, which Roger oversells with the first Careful With That Axe, Eugene scream since Oakland ‘77.

-

Thank you! I'm guessing Ohhara and Mach Hayato knew each other, then.

-

Puroresu History on Indefinite Hold [NEW UPDATE]

KinchStalker replied to KinchStalker's topic in Puroresu History

This is the final update. I received my new laptop on Monday. It's in the midrange of what I wanted, but it will serve my needs much better than the 2009 HP. However, I am taking a small vacation from serious puroresu research. This is where I feel I need to pull back the curtain for you guys. For the past two years, my transcription and research have not just been a hobby, but my life. I can afford to invest so much time into it—in other words, I can afford to transcribe entire books with an app that only transcribes four characters at a time—because I am unemployed and live in a residential care situation. It has been rewarding to accidentally become an expert on Showa period puroresu, don't get me wrong; there is still a great thrill to uncover so much information that was simply never going to get through to the West, filtered as that range of knowledge has been through Meltzer (and Fumi Saito). It is not a life I can live forever, though. The tedium of transcription, which you could definitely feel seeping into my Four Pillars book recaps, has been very taxing on my mental health (the best analogy I can make is to imagine if you were forced to sit down and solve hundreds of captchas every day). There are simply no English-language resources that are of any use to me when it comes to detailed historical coverage of puroresu. This has been such a major part of my life that I have literally not read a book in years. When I went to AEW's Portland show in January, I knew nobody, and felt the loneliest I had in a long time. I have made friends through wrestling, to be sure, but they're all screen friends. I want to build a healthier, more sustainable relationship with this hobby in 2023. I am planning to find some part-time work this year that will not impact my benefits. This will cut into the time I have to transcribe Japanese materials, but I hope that I can use extra funds to commission proper translations of Japanese articles. I want to spend time to make some in-person social connections. I certainly want to continue my weight loss! (I was 310 last February and have gone down to 265. I want to at least be under 230 by the end of the year.) So, please do not expect much from me here for a little while. Right now, the only puroresu work I am doing is a longhand draft of the first chapter of a Jumbo biography, which I am writing out to assess what details I may need to seek an interview with Tsuruta's brother to gather. (Hopefully I can give the guy some money to answer my questions.) Meanwhile, I am reading my first book in years. It's one that I only got halfway through in 2016; getting dumped by my high school sweetheart left me in no condition to finish it. But it has stuck in my mind ever since, and I started my second attempt a few days ago. I used to be a hardcore literature guy, if you can believe it (my handle, which I have used since high school, is partially a Ulysses reference). Really want to get back in touch with that part of myself. I apologize to those who were anticipating a rush of productivity when I got my new laptop. But if I am the only person who does what I do (at least for the old stuff), then I have a responsibility to make this work more sustainable on my end. I cannot kill myself trying to tell their stories: not if I want to get through telling them. -

Rashomon Tsunagoro (羅生門綱五郎) Profession: Wrestler Real name: Zhuo Yiyue Professional names: Zhuo Yiyue, Niitakayama, Rashomon Tsunegoro Life: 3/5/1920-unknown Born: Taiwan Career: 1954-1957 Height/Weight: 203cm/125kg (6’8”/276lbs) Signature moves: single-leg crab Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association Titles: none The tallest man in puroresu for its first several years, Rashomon Tsunagoro is more noted now for his subsequent acting work. Standing at 6’8”, the Taiwanese Zhuo Yiyue entered sumo through the Hanago stable in 1940. First given the name Niitakayama, after the name given to Taiwan’s tallest mountain when it was a subject of Imperial Japan, Zhuo changed his name to Izuminishiki. He retired in 1946 after having stalled out at the makushita division. Eight years later, Zhuo entered pro wrestling through the JWA, and would go by various names through a four-year stint. The tallest man in puroresu until Giant Baba, for whom he has been mistaken by modern viewers, the man best remembered as Rashomon Tsunegoro was noted for his tag team with a former stablemate, the 5’6” Fujitayama. As the JWA entered its first decline, Rashomon left wrestling in late 1957. He would make a successful pivot into acting, as his frame found him steady work as a bit player in late 50s and early 60s productions. The most notable of these, certainly to Western audiences, was as a henchman in Akira Kurosawa’s classic Yojimbo. Rashomon stands out in Yojimbo.

-

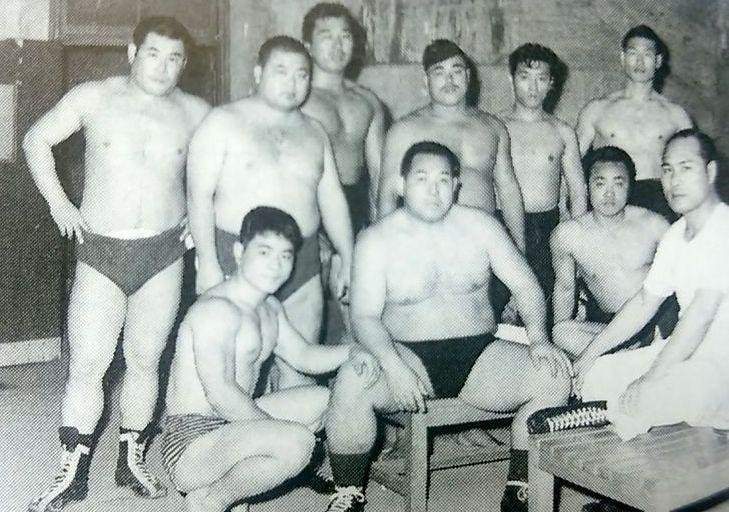

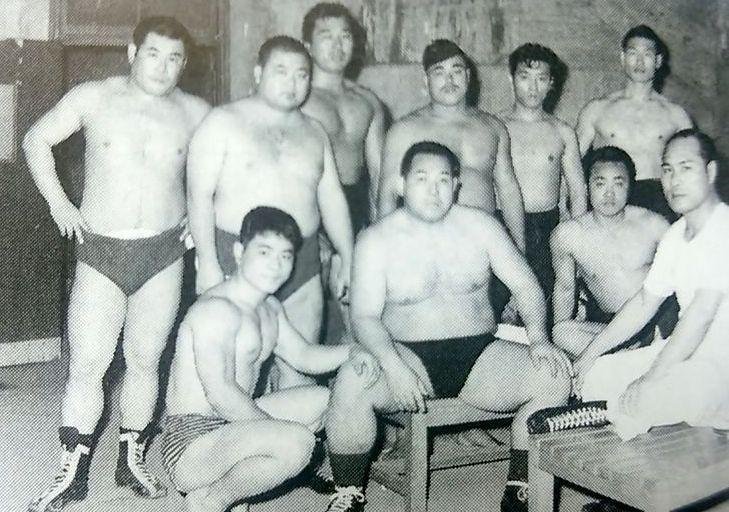

Hideyuki Nagasawa (長沢秀幸) Profession: Wrestler, Referee, Executive/Miscellaneous Real name: Hideyuki Nagasawa Professional names: Kaichi Nagasawa (長沢日一), Toranosuke Nagasawa (長沢虎之助), Hideyuki Nagasawa, Tiger Chung Lee Life: 1/2/1924-1/10/1999 Born: Osaka, Osaka, Japan Career: 1954 Height/Weight: 176cm/85kg (5’9”/187lbs) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association, Japan Wrestling Association, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none The last active Japanese wrestler to have been born in the Taisho period, Hideyuki Nagasawa never had what it took to be a top star but had a quarter-century career in and out of the ring. Nagasawa stands at far left in an AJPWA roster photo. A Dewanoumi wrestler who left sumo for the military, Hideyuki Nagasawa did not return to Tokyo when he was demobilized. Instead, he became a salaryman in Osaka who competed for a corporate sumo team, but returned to professional sport when he joined Toshio Yamaguchi and Umeyuki Kiyomigawa’s All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. He worked on the AJPWA’s shows as well as on various JWA dates through 1954. As the AJPWA collapsed in 1956, Nagasawa moved with Yamaguchi to wrestle shows out of Toshio's native Mishima. In October 1956, Nagasawa entered the Japan Weight Class tournament, a series of three interpromotional tournaments intended to delegitimize the JWA’s competitors and scout talent worth swiping. As the heavyweight bracket began at the International Stadium on October 23, Nagasawa was eliminated in the first round by eventual winner and former yokozuna Azumafuji. As the story goes, he was watching the show from the back of the venue when Rikidozan arrived and asked how he was doing. Nagasawa admitted that he was contemplating retirement for various reasons, but that if Rikidozan wanted him, he would join the JWA. Nagasawa got a call from Toyonobori, and he was working on JWA shows the following month. He would be one of five regional wrestlers hired by the JWA, alongside Michiaki Yoshimura, Kanji Higuchi, Yuichi Deguchi, and Kiyotaka Otsubo. Anecdotal evidence paints Nagasawa as a man who could handle himself. During a show in Taiwan, Yoshinosato is said to have suggested to Rikidozan that Nagasawa, instead of himself, fight a local kenpo practitioner who had challenged the JWA. Antonio Inoki and Motoyuki Kitazawa both attested to his strength. Regardless of whether Nagasawa really was as tough as some have claimed, it is clear that he did not have what it took to be a top star, even if that may have been more a function of temperament than talent. That is not to say that Nagasawa did not make valuable contributions. In fact, he was the JWA’s first head coach. The first several years of puroresu were entirely populated by wrestlers had prior experience in sumo, judo, or amateur wrestling, but not long after Nagasawa joined the JWA, those that I call the Second Generation of puroresu began to enter the company. Kitazawa praised Nagasawa as a kind man who could deal with everyone, “from new apprentices to old-timers, without dividing them”. He was also responsible for looking after foreign wrestlers, although it is unspecified as to whether Nagasawa spoke English. In March 1960, after Mammoth Suzuki infamously chickened out, Nagasawa was brought with Rikidozan on his second and last trip to Brazil. The two wrestled there for four weeks; they also met Kanji Inoki. Speaking of him, it was once reported that Inoki’s first match billed as Antonio was against Kintaro Oki on November 7, 1962. However, a recent revised edition of Team Full Swing’s book of complete Inoki match results corrected this: it was against Nagasawa two days later. By the mid-sixties, when Otsubo had taken over as head coach, Nagasawa rarely wrestled and was often seen dismantling the ring at the end of shows. Kitazawa recalls that this bothered him, and that he had tried to help his senior, but that Nagasawa said it was okay, and that it was his job. In 1966, in the corporate restructuring after Toyonobori’s acrimonious departure, Nagasawa was named a director of the JWA alongside Giant Baba. He would stay with the JWA until the end, working as a referee. After that, he got a job with the IWE’s materials department. Like others originally hired for the IWE’s ring crew, namely Ichimasa Wakamatsu and Hiromichi Fuyuki, Nagasawa would find himself back in the ring. By this point, Nagasawa was the last active Japanese wrestler born in the Taisho period. At first, he wrestled under a mask as Tiger Chung Lee, but he would wrestle as himself for most of this stint back in the ring, which lasted until a match against Tsutomu Yonemura in October 1976. After this, Nagasawa remained with the company until shortly before its demise. He died in 1999.

-

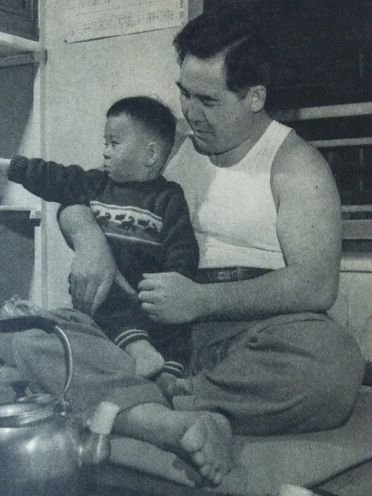

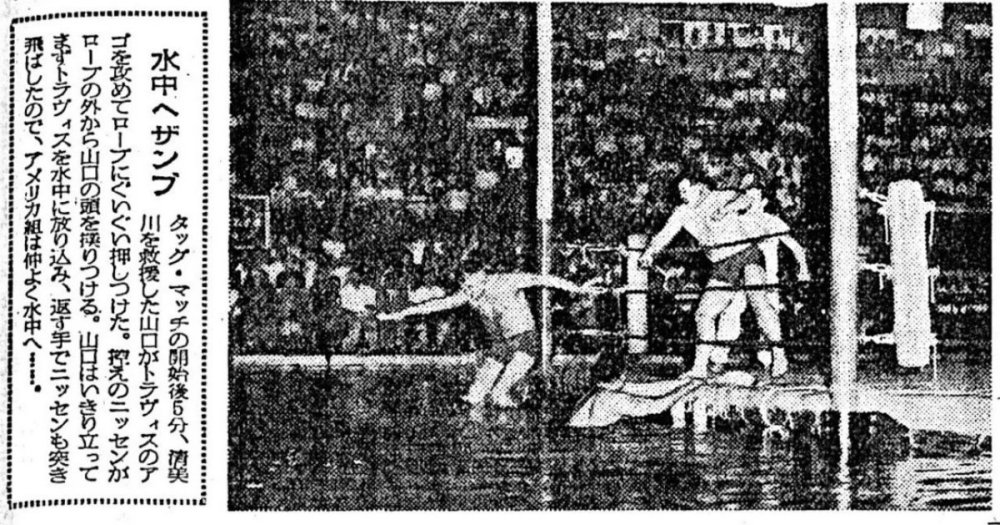

Toshio Yamaguchi (山口利夫) Profession: Wrestler, Promoter Real name: Toshio Yamaguchi Professional names: unknown Life: 7/28/1914-4/1/1986 Born: Mishima, Shizuoka, Japan Career: 1951-1958 Height/Weight: 180cm/115kg (5’11”/254lbs.) Signature moves: tackle Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association/Yamaguchi Dojo Titles: none Now too often forgotten, Toshio Yamaguchi was a puroresu pioneer whose All Japan Pro Wrestling Association was a significant regional promotion. Yamaguchi (right) in Hawaii in 1951. Masahiko Kimura is right next to him. (Image credit: Facebook user Ryosuke Ratel Nasa) Before the war, Toshio Yamaguchi made his name as a skilled judoka, first as a member of Waseda University’s club, and then as an employee of the South Manchuria Railway, where he was nicknamed the Manchurian Tiger. He entered the original incarnation of the All-Japan Judo Championships four times between 1935 and 1941, notching third and second-place in his division in 1936 and 1937. In 1939, he made a brief switch into sumo and entered the Dewanoumi stable. Due to Yamaguchi’s pedigree, he was initially allowed to compete in the makushita division as a makushita tsukedashi, but a poor showing in his debut tournament led him to be demoted. After a second tournament, in which he competed as Daigoro Yamaguchi, he was drafted and forced to retire. I don’t have anything on Yamaguchi for the rest of the forties, but in 1950, he was a founding member of the International Judo Association. I plan to someday cover the IJA, often called Pro Judo for short, in detail for a PWO thread or blog post. But to summarize, it was a brief yet significant antecedent to puroresu. As Kodokan shifted its strategy to promote judo as an amateur sport—a desperate measure to survive under American occupation, and to get judo back into the phys-ed curriculum—Tatsukuma Ushijima sought to pave another road on which impoverished martial artists could make a living as sports-entertainers. IJA events, which began in April 1950, offered judo matches with loose rules. Draws and decision wins were out: joint techniques and bodyslams, in. Entertainers like Keiko Tsushima, who you may know from Seven Samurai, and Koji Tsuruta also sang and danced in segments of these shows. Behind the legendary Masahiko Kimura, Yamaguchi was the IJA’s second strongest judoka. That June, the two signed a contract to work in Honolulu in October, but a lawsuit from the IJA kept them in Japan until the following year. By that point, though, the Association’s support from construction company Takagi Corporation had been withdrawn, and it hadn’t held a show in two months. Kimura went in January to hold a seminar at Hawaii University. When Yamaguchi arrived the following month, the two appeared on shows promoted by the Matsuo brothers while being trained in pro wrestling by their manager, Rubberman Higami. After they were finished with the Matsuo contract, Kimura and Yamaguchi began work for promoter Al Karasick, who would spearhead American pro wrestling’s export into Japan through the Torii Oasis Shriners Club tour of the late year. Over the next year, Yamaguchi and Kimura wrestled in North America and Mexico, as well as compete in their original sport on a famous trip to Brazil. In April 1952, Yamaguchi even teamed up with Rikidozan on a California show. Back in Japan, both Yamaguchi and Kimura participated in Osaka juken shows, which pitted judoka against boxers of foreign descent. These had a decades-long history, and had most notably been held to promote boxing in the 1920s, but the juken revival was the responsibility of future joshi promoter Morie Nakamura. In July 1953, news of the formation of the Japan Wrestling Association triggered further development. On July 18, less than three weeks after the JWA had been established, a juken show at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium, which was a charity event for Kitakyushu flood victims, was headlined by a judo vs sumo match in which Yamaguchi fought the retired rikishi Umeyuki Kiyomigawa. According to a column called “The Birth of Kansai Pro Wrestling”, written by former Mainichi Shimbun sports head Katsuhisa Tanaguchi for Hiroshi Tazuhama’s 1975 book 20 Years of Japanese Pro Wrestling, the origins of the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association laid in a translation of the Mainichi article on the show. It piqued the interest of a GI stationed in Osaka at the time, who approached Yamaguchi and claimed that he was the manager of a wrestler named Bulldog Butcher who wanted to wrestle him. (In reality, Butcher was his commanding officer.) Yamaguchi was initially uninterested, but the proposal caught the ear of Shotaru Matsuyama, the head of a local yakuza gang called the Sarae-gumi. Matsuyama went to Mainichi to make a formal request to hold this show, and this led to the formation of the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. (Yamaguchi had first suggested a regional name, like Kansai or West Japan.) The AJPWA's first show was at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium on December 8, 1953. Two months later, they beat the JWA to the punch with puroresu's first television broadcast. On February 6 and 7, 1954, they booked the OPG for two well-drawing shows sponsored by Mainichi as well as the Manaslu mountain-climbing team. (Hey, whoever wants to help you promote your show.) These shows were broadcast live in the Kansai and Tokai regions as an experiment by NHK. Twelve days later, Yamaguchi began work on the JWA’s first tour alongside others in his organization. The AJPWA resumed work in April, although records of its shows are inadequate. When Kimura challenged Rikidozan in the paper that autumn, Yamaguchi threw his hat into the ring by stating his challenge to whichever man won. On December 22 at the Kuramae Kokukigan, on a show where AJPWA wrestler Noburo Ichikawa was brutally beaten by Junzo Yoshinosato, Rikidozan shot on Kimura in the main event. On January 26, a JWA-AJPWA joint show saw Yamaguchi challenge for the Japanese Heavyweight title. Unlike with Kimura, Yamaguchi's title shot was all business, and he even lost two falls to the champion, albeit by countout. This was the last heavyweight title match between two natives for 18 years, until Rusher Kimura challenged Strong Kobayashi for the IWA World Heavyweight title in July 1973. The first of the AJPWA's famous pool shows. While it was completely dependent on American servicemen for opponents—the only foreign professional wrestler who worked with them was PY Chang, the future Tojo Yamamoto—the Association distinguished itself with gimmicks. The AJPWA was puroresu's first, and for decades, only intergender promotion, and also featured midget wrestling. The Association also held shows at Osaka's Ogimachi Pool, starting with a televised one on September 25, 1954. While they did not invent the wrestling show-in-water, which had roots in the 1930s, the AJPWA's Ogimachi shows were the first such events in puroresu, and they predated FMW's revival of the gimmick by over thirty years. Trouble came in 1956. The same year that Rikidozan’s patron Shinsaku Nitta died, the first omen of a three-year decline that nearly killed puroresu, Matsuyama fell ill and withdrew his AJPWA support. Yamaguchi and his faithful, which did not include Kiyomigawa, left Osaka that summer for Toshio's hometown of Mishima, where they ran shows in poverty under the Yamaguchi Dojo banner. (The Osaka market would be filled by the short-lived Toa Pro Wrestling, formed by Korean-born Daidozan.) That autumn, Yamaguchi had his last significant matches in the Japan Weight Class tournament. Held by the JWA to delegitimize its regional competitors and scout talent that were worth poaching, the tournament saw Yamaguchi advance to the finals of the heavyweight division, which was meant to set up a Rikidozan title defense that was never booked. After their first match went to a draw, Yamaguchi lost the final by countout to former yokozuna Azumafuji. After this, four of his wrestlers were raided by the JWA: Michiaki Yoshimura, Kanji Higuchi, Yuichi Deguchi, and Hideyuki Nagasawa. According to Showa Puroresu, Yamaguchi Dojo was dissolved in September 1957. Yamaguchi retired the following year, holding two last Osaka pool shows on May 31 and June 1 with guests ranging from Yoshimura to Kimura. He died in his hometown of heart failure in 1986. Yamaguchi sits with the AJPWA roster.

-

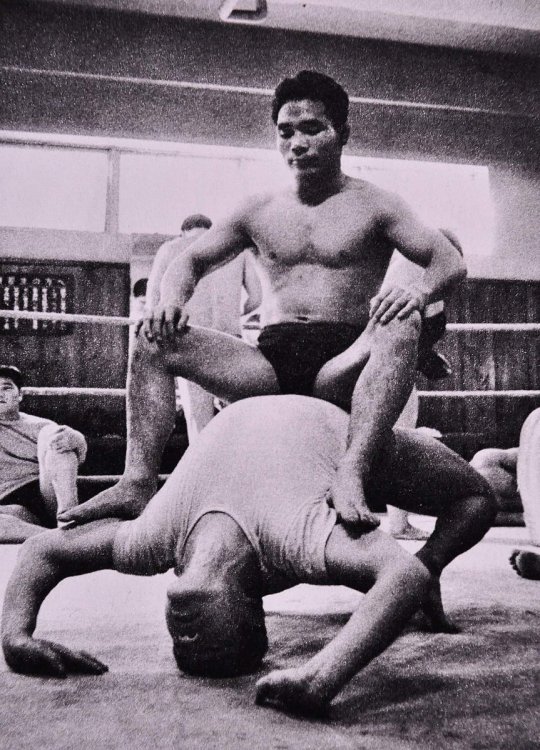

Kiyotaka Otsubo (大坪清隆) Profession: Wrestler, Trainer Real name: Kiyotaka Otsubo Professional names: Kiyotaka Otsubo, Hishakaku Ootsubo Life: 7/10/1927-7/29/1982 Born: Tottori or Tokyo, Japan (sources vary) Career: mid 1950s-1971 Height/Weight: 170cm/93kg (5’7”/205lbs.) Signature moves: Boston crab Promotions: International Pro Wrestling (Kimura), Japan Wrestling Association Titles: none Kiyotaka Otsubo was most important as an early puroresu trainer. Otsubo sits on Antonio Inoki as he performs a neck bridge. [THIS PROFILE IS BEING REWRITTEN.]

-

Toshio Komatsu (小松敏男) Profession: Referee, Announcer, Executive (Sales) Real name: Toshio Komatsu Professional names: not applicable Life: 3/3/1925-unknown Born: Kochi, Shikoku, Japan Career: 1954-1966 Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling (as executive) One of the JWA’s first referees, Toshio Komatsu transitioned into announcing in the early sixties before retiring to become a promoter. The fourth of eight children born to a Kochi realtor, Toshio Sento took the family name Komatsu when he entered school. Like just about all of his family, Toshio was a sumo fan, and competed in local tournaments alongside his eldest brother behind their mother’s back. Upon graduating junior high, he moved to Tokyo against his mother’s will to join a stable. In March 1941, he joined the Nishonoseki stable despite being far under the required weight at the time: a traditional measurement equivalent to about 73kg (160lbs). Komatsu claimed that he failed the first measurement, but that Oyama Oyakata had told him to try again, and that Oyama then recorded what the scale had measured at the moment he had jumped onto it. Sumo only had two tournaments a year at this time, so Komatsu had little experience before he was drafted. In September 1942, he was sent to the Malay peninsula as a private in the 44th Industry Regiment, and served as a light machine gunner. He did not see any battles himself, but he may have narrowly avoided death. An order to report for a cadet examination had separated him from his platoon just before they set out to attack a group of “communist bandits” in Johor Bahru, who had prepared to fire at them from the opposite bank. After the war, Komatsu remained in Malay as a laborer until he was demobilized in December 1947. He had given up hope of entering sumo shape again; as a matter of fact, a rumor had spread amongst his former stablemates that he had been killed on his way home, in a Korean riot. Toshio first found a job in Kochi, where he had first set foot back home, but after six months, he moved to Kyushu, where he worked in a coal mine for two years. Upon his return to Kochi, an acquaintance from Yokohama reintroduced Komatsu to his former stablemate Rikidozan. By this time, Rikidozan had retired from sumo to work for the construction company of patron Shinsaku Nitta, for which Komatsu would also work. Komatsu was in attendance when Rikidozan wrestled his first match against Bobby Bruns: “Riki-san was wearing a yukata with a large lobster pattern dyed on it as a gown, and within five minutes his belly started to ripple, which kept me on the edge of my seat.” When Rikidozan left for Hawaii in 1952, Komatsu was the one who babysat Yoshihiro and Mitsuo Momota. Komatsu continued to work for Nitta Kensetsu for the rest of the fifties, as he spent six years building pavilions for fireworks shows in the Ryogoku river festival. He even hired trainees at the Riki Gym, led by a young Hisashi Shinma, to serve as nightwatchmen and prevent theft. However, Rikidozan “forcibly recruited” Toshio in the spring of 1955. He was initially promised a job as a clerk, but second referee Yoshio Kyushuzan was weary of officiating all but the last two matches of each show. Komatsu became the JWA’s undercard referee. Five years later, he was forced to take the job that would make him famous. In the JWA’s early years, they had hired a freelance announcer, one Mr. Sakae, to call most matches. This ended on May 11, 1960, when Sakae received a telegram to come home. Rikidozan made Komatsu take his place on the spot. Komatsu modeled his calls after Naoyoshi Akutsu, a boxing announcer that the JWA had borrowed for big matches. It was rough at first. When the JWA began broadcasting weekly at the Riki Sports Palace, Toshio thought he looked “as if his face was on fire” and began practicing with a mirror. He also made various mistakes, such as calling Mr. Atomic “Mr. X” and announcing Kiyotaka Otsubo as “Tsubo-yan”. He claimed that he once made the latter error three times in a row, and if the translation is correct, Otsubo mooned him in response. Komatsu's voice was not pretty, but it had power, and the “Komatsu bushi” became the most iconic puroresu call for decades. He appeared in commercials for Mitsubishi appliances where he called product models “in the red and blue corners”. Komatsu was the only announcer to appear in commercials until Kero Tanaka in the 1980s. Nowadays, his greatest legacy is calling the last surviving Rikidozan match: against the Destroyer, on December 2, 1963. Komatsu continued as an announcer until a shift to the sales department in 1965, upon which he was replaced by Nagaaki Shinohara. When the Tokyo Metropolitan Police cracked down on the JWA, they did not just pressure the top shareholders with criminal ties to resign. They also forced the company to purge all but seven of the local promoters that they had sold shows to. The JWA could no longer run many of the buildings that they had built their circuit on, and the department scrambled to find new connections. Komatsu flew back to Shikoku Island, where a close friend of his brother was the head of the Kochi Shimbun newspaper’s sports department. Through that connection, he won the support of the island’s newspapers. Despite this success, Komatsu left the JWA that summer. He was unable to keep up with the sales quotas that the top executives had enacted “only out of immediate greed”. (I suspect this was a dig at Kokichi Endo.) After that, Toshio spent the next decade as an independent promoter, although he briefly returned to announcing for Tokyo Pro Wrestling. Komatsu spent the first two years in Tokyo, where he organized jazz and group sounds concerts. He claimed that he had promoted concerts by nearly every major band in the latter genre, “except the Spiders”, but his calls on other promoters to help him build a tour circuit were abandoned by his would-be partners. After cleaning up that mess, Komatsu eventually returned to the wrestling business and settled in Kochi: “[…] I knew I could not betray [wrestling], and it eventually helped me to stabilize myself mentally and financially.” The 1979 Monthly Pro feature reports that Komatsu refused to gouge ticket prices on his shows; the best seats were always six thousand yen, and every seat below sat at a fixed rate. In 1972, he was one of the first promoters to give New Japan Pro-Wrestling any proper support. Eventually, his reliability got him a job with the Matsunaga brothers, who entrusted him with setting up AJW’s western tours. On January 11, 1980, Komatsu picked up the house mic one last time for Jumbo Tsuruta’s NWA United National title defense against Billy Robinson. Komatsu attends AJW's February 1979 Budokan show.

-

UPDATES, FEBRUARY 2023 Generally, I have only made minor adjustments and additions to profiles in the six months since I posted my last proper update. The exception was a major expansion of Mammoth Suzuki's profile. But it was only in February that I added any new profiles. Also, this month saw the debut of joshi profiles, courtesy of the Sensational, Intelligent @Noah's_Savior! New Profiles Donald Takeshi (Wrestler, JWA/NJPW) Haruka Eigen (Wrestler/Executive, Tokyo Pro/JWA/NJPW/JPW/AJPW/NOAH) Haruko Ogawa (Wrestler, AJW) Hitoshi Yoshida (Executive, AJW) Junzo Yoshinosato (Wrestler/Broadcaster/Executive, JWA/IWE) Katsuhisa Shibata (Wrestler/Referee, Tokyo Pro/JWA/NJPW) Kyoko Okada (Wrestler, AJW) Maki Ueda (Wrestler, AJW) Motoyuki Kitazawa (Wrestler/Referee, JWA/Tokyo Pro/NJPW/UWF) Oscar Ichijou (Wrestler, AJW) Peggy Kuroda (Wrestler, AJW) Yusuf Turk (Wrestler/Referee/Executive, AJPWA/JWA/NJPW)

.jpg.382349e312a159e3836c58fc608a8424.jpg)

.jpg.fe8b83a1cbd5cb20dbe0a4ec8045d776.jpg)

.png.769a03406ccb75fcb5b7b70b505ad13d.png)

.jpg.5cadc969292b16a6cede69c37ee7a666.jpg)

.jpg.e1f1e325baeae17b56435f9356da832a.jpg)