-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

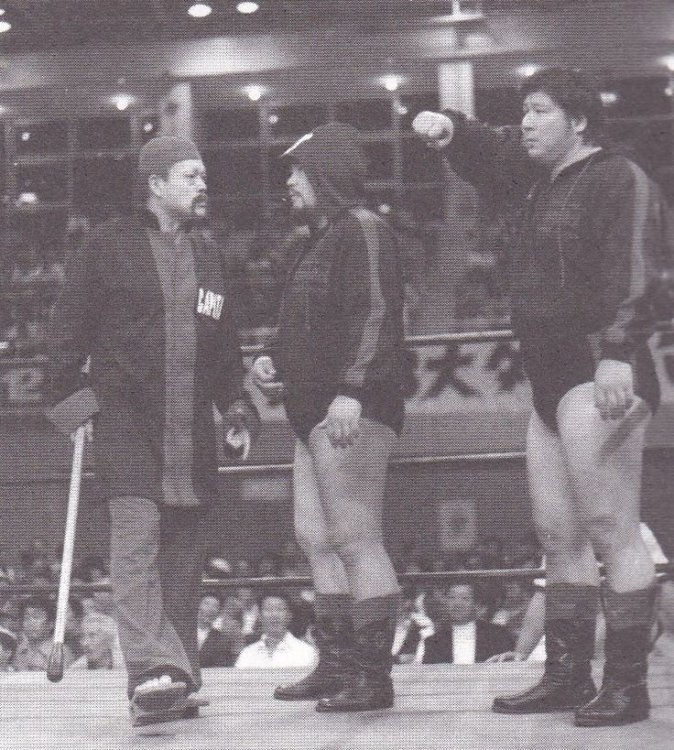

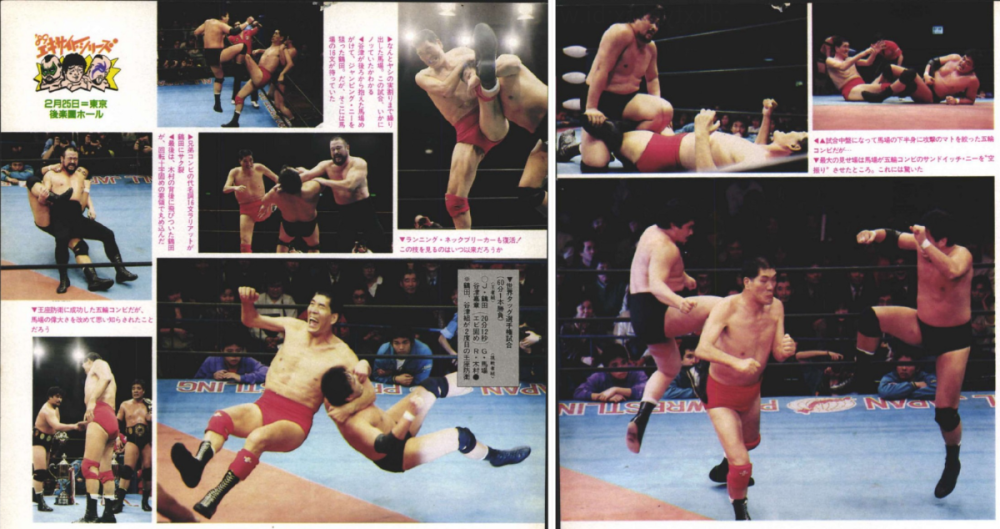

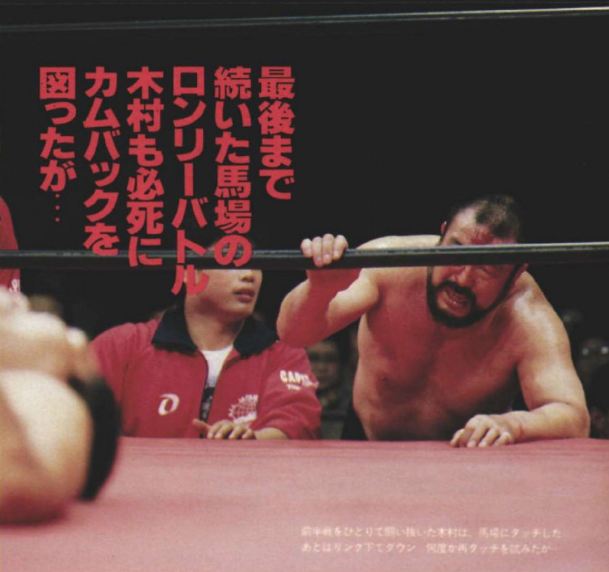

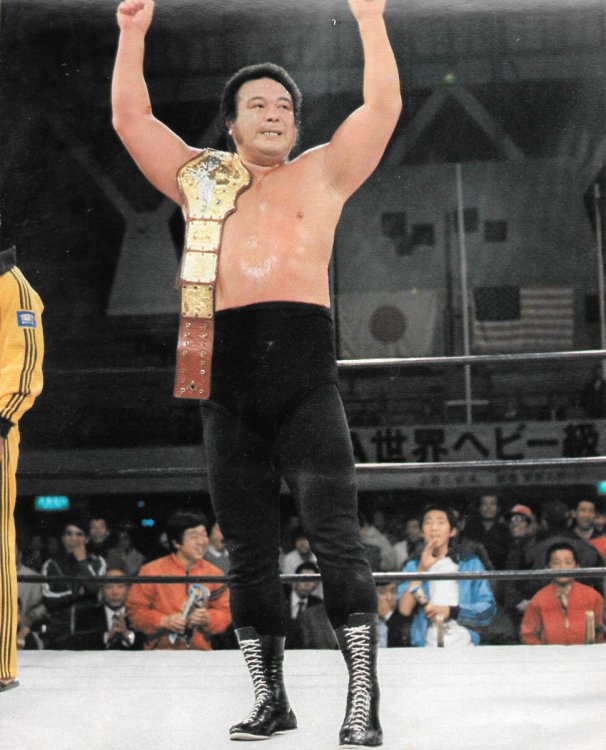

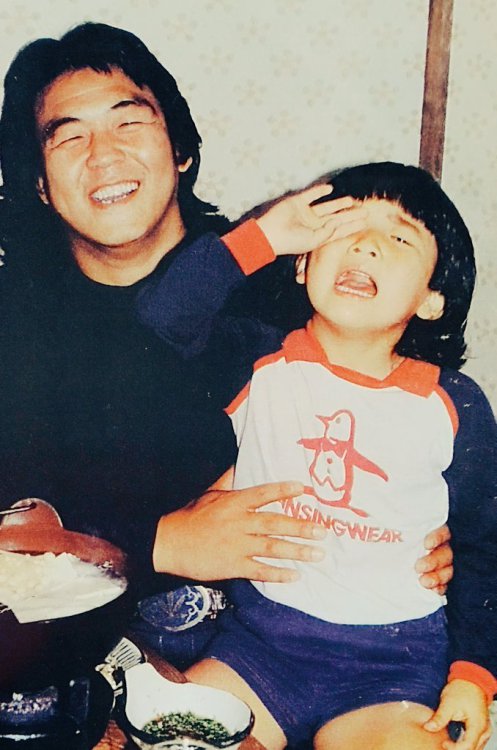

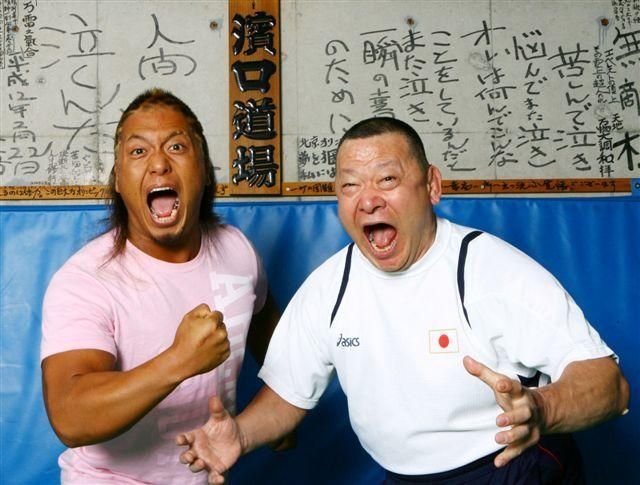

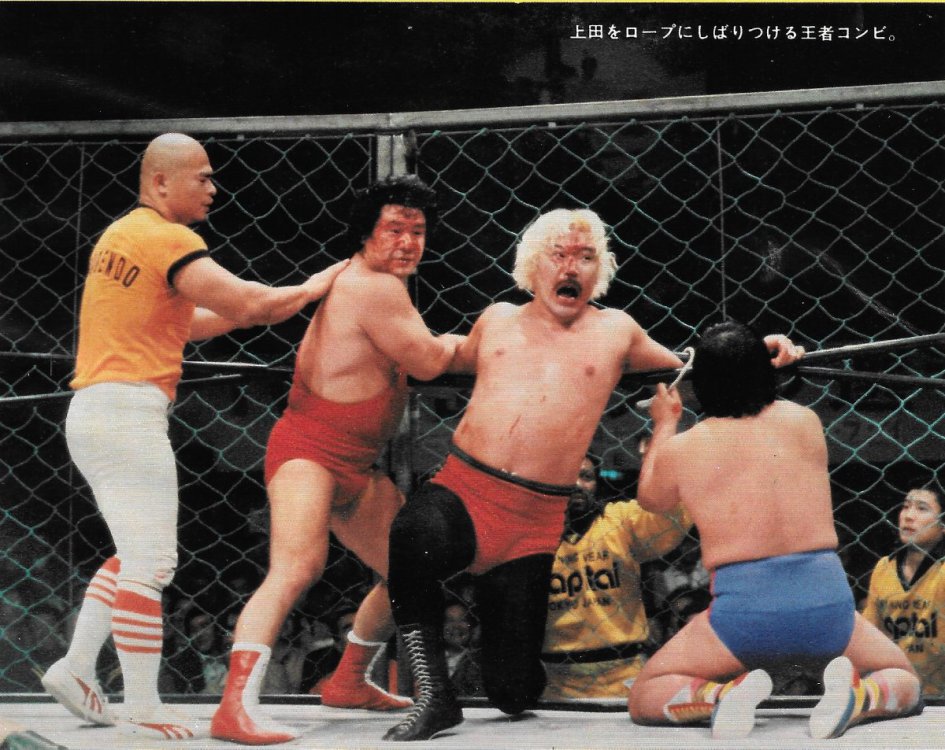

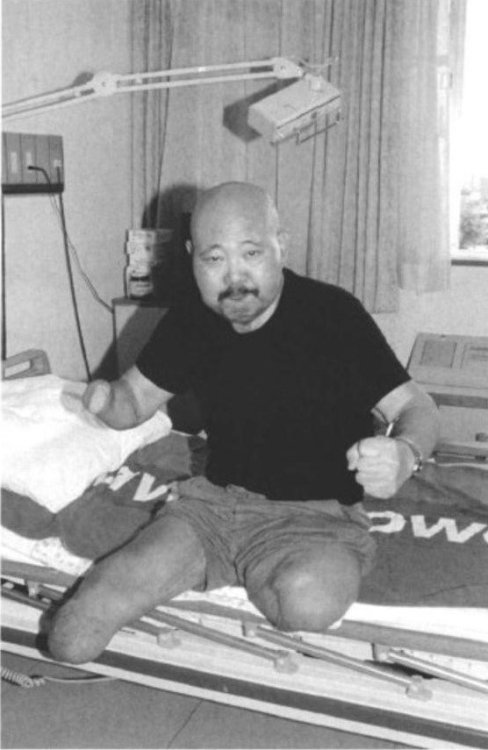

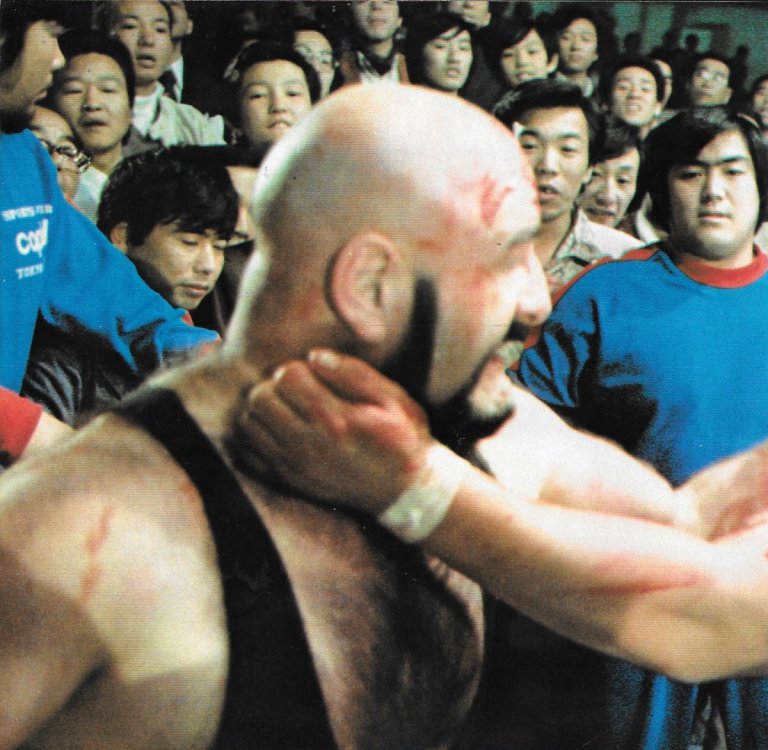

PART FOUR: ENDURE AND BURN (1989-2010) Rusher Kimura’s final title shot came in February 1989. By this point, Giant Baba had begun to hold secret creative meetings with Weekly Pro Wrestling editor-in-chief Tarzan Yamamoto and All Japan reporter Hidetoshi Ichinose. Central to Yamamoto’s strategy to revitalize AJPW was a focus on its shows in Korakuen Hall, and several matches were booked early in the year to stimulate the “myth” that he believed the company needed to develop. One of these matches, which occurred on an untelevised show on February 25, was Baba & Kimura’s shot at the Olympians’ AJPW World Tag Team titles. The “Brother Combi” survived for twenty minutes until Kimura took a Tsuruta pinfall. Rusher in the Brother Combi's famous 1989 RWTL match against Genichiro Tenryu & Stan Hansen. Kimura only had half a dozen televised matches that year, all of which took place in its second half. Two of these were six-man tags with glimpses of the comedic tradition that was soon to develop in AJPW’s midcard. For instance, see the match on the July 16 Bruiser Brody memorial show, in which Baba & Kimura teamed up with John Tenta against Tsuruta, Masanobu Fuchi & the Great Kabuki. In the match’s most memorable spot, Tenta teased a tope against Kabuki before Rusher blocked him from going through (and possibly breaking the ring in the process). His most famous televised match of the year came during the 1989 Real World Tag League, when he & Baba faced Genichiro Tenryu & Stan Hansen in a doomed Sapporo standoff on November 29. It is one of my favorite matches of all time, and a career highlight for Kimura. As Hidetoshi Ichinose covered in his 2019 book, this match helped All Japan build a strong foothold in the northern city, as it was their last show at the Nakajima Sports Center for six years to draw under five thousand. That was the last RWTL that the Brother Combi would enter together. While Baba continued to participate in the tournament through 1996, Kimura only worked the next two iterations alongside Mighty Inoue. In spring 1990, Rusher began a feud with Tenryu—even using poison mist for the first time in his career in a tag match—that was aborted by Tenryu’s departure for SWS. (Kimura struck at Megane Super in a promo as retaliation, urging the audience to never buy glasses from them.) Two years later, when Akira Taue was injured in the Champion Carnival tour, Kimura was slotted in his place for the most ambitious match of early-90s All Japan: the first “survival tag” at the 1992 Fan Appreciation Day show. A tag-team analogue to NJPW's 5vs5 gauntlet matches, it was conceived by booker Masanobu Fuchi as an attempt to top the already-legendary 1991 Fan Appreciation Day six-man. But these were outliers in Kimura’s work from this point forward. Baba and Kimura formed the core of the Family Gundan faction, whose six-man matches against their “villainous” counterpart Akuyaku Shokai, which were nicknamed the Fami-Aku Kessen (“family-bad showdown”), became a staple of the All Japan product. This formula allowed Baba and Kimura to continue to work in a comedic and low-impact style in provincial markets where they were still primary draws. The early departure of the Great Kabuki (and an unsuccessful attempt to bring Goro Tsurumi on board, before he went for SWS like Kabuki) left the role of their third partner to often fall on Mitsuo Momota, who had long been known as AJPW’s “6:30 Man” for his ubiquity as a barrier for young wrestlers on opening matches. Much of the motion in Fami-Aku matches was between Momota and Haruka Eigen, Akuyaku Shokai’s most consistent member. Their dynamic was likely influenced by Eigen’s undercard matches against Don Arakawa in early-80s NJPW. But it was Rusher who would often facilitate one of Eigen’s staple spots, in which Kimura would bend Eigen back while he stood on the apron and chop him in the chest, causing Eigen to spit hard into the crowd. (While I have not researched enough to confirm this myself, Kimura may have inherited this spot from Akuyaku member Motoshi Okuma. He is seen performing the spot in a September 1989 singles match against Eigen, which was broadcast in 2022.) Kimura may have been one of the least mobile performers in these matches, but his character was a crucial component, and his postmatch promo was a highlight of the AJPW house show. Kimura gets a laugh from the comedy duo Utchan Nanchan, appearing as guest commentators. Kimura’s promos were not popular with their targets, but Baba, Okuma, Eigen, and Fuchi all had to grin and bear them because of their popularity with audiences. Fuchi was the target of one of Kimura's greatest bits. Night after night, Rusher roasted All Japan's eternal bachelor. He offered Fuchi's hand to an elderly spectator. He said he would offer the hand of a family member, before quickly retracting that out of the dreadful proposition of becoming Fuchi's brother-in-law. On one occasion, he recited haiku for each of his opponents, ending with the punchline "Fuchi, get a wife soon" (“Fuchi senshu/omae wa hayaku/yome morae”). Fuchi's mother once called Kimura's house, telling Hiroshi to tell his father "not to say bad things about her son". He did not stop. Kimura in an advertisement for Teppan noodles. AJPW trainees Satoru Asako and Masao Inoue blow into the furnace. Kimura's promos revitalized him as a presence in popular culture. Rusher appeared on talent show Yuji Miyake's Isu Band Heaven as a celebrity judge in 1989. On Ken Shimura's sketch comedy show Shimura Ken no Daijōbu Da, ensemble member Nobuyoshi Kuwano performed a Kimura impression that would interrupt sketches to cut promos. While he cut his promos off the cuff, and Mitsuharu Misawa’s later suggestions of topical material were ignored, Kimura took his house show promos seriously. It has been corroborated by Jun Akiyama and Kyohei Wada that Rusher researched local landmarks, famous persons, staff at the venue, and more. In a 2020 column for Tokyo Sports, Wada recalled that, after his face turn, Rusher began to ask him about local specialties before each match: “In Akita, it would be kiritanpo, in Hakata, mentaiko (cod roe). In Nagoya, he would say, ‘Fuchi, today we will have a bowl of chicken wings and finish with miso nikomi udon.’ In Sapporo, ‘Fuchi, you were unusually spirited today, but you ate Jingisukan ["Genghis Khan"; grilled mutton] before the match, you son of a bitch.’” Even the low-impact Fami-Aki matches took a toll on the broken man. Kimura received a special ankle cast from Baba, which he was forced to wear under a ring shoe. (Hiroshi remembers being concerned about its tightness.) The walk to the ring was the worst part of his job, and Rusher hated stage sets with steps. Despite this, Kimura would join NOAH in 2000 as its eldest charter talent. On June 24, 2001, he wrestled a 60th birthday match with Momota against Eigen & Tsuyoshi Kikuchi. Even with the death of Baba and the absence of AJPW remnant Fuchi, NOAH featured spiritual successors to the Fami-Aki matches of the previous decade. A new bit from this period came in the ring, where Kimura would attempt to finish a match with an exploder suplex but was always cut off. His final match came on March 1, 2003, a tag with Momota against Eigen & Kishin Kawabata. Kimura was sidelined after this for poor health. He went to Keio University Hospital for rehabilitation, but by this point, his back and legs were so damaged that even sitting down was too much. The surgery during his All Japan years had not gone well, and Rusher’s spinal stenosis had only worsened since. That July, Kimura suffered a stroke while at a sauna. However, Rusher did not disclose this to NOAH. Hiroshi states that his father wanted to die in the ring, and that Rusher had told Misawa and NOAH director Kenichi Oyagi that “he could walk if his back stopped hurting”. According to Hiroshi, Kimura did not know that it would be impossible for him to wrestle again after the stroke, and Misawa had taken him at his word. NOAH threw money towards a rehabilitation that never would have been successful, as Misawa searched for doctors to help Kimura recover. NOAH rented an apartment in Tottori for Kimura to work with a sports therapist. In a revealing anecdote, Hiroshi recalls a major argument with a NOAH employee who, unaware of the severity of Rusher’s condition, had prepared a bed for able-bodied people that his father never could have slept in. To Hiroshi, it is clear that they wanted Kimura to return for Departure, their first Tokyo Dome show in 2004. Oyagi went so far as to say that he didn’t care if he had to come in a wheelchair. But Kimura did not want to. He ultimately recorded a promo for a video package to be played during the show, but even this had been something he felt “made to do”. As hard as it was for him, though, Hiroshi remembers something Oyagi had said when Kimura stopped wrestling: “Mr. Kimura, you’re a lucky man. If this had happened in All Japan, you would have been fired.” Misawa appointed Kimura as an honorary chairman as a way to give him a pension. This lasted for the rest of Kimura’s life, although his pay was cut in half around 2007 due to NOAH’s financial difficulties. He continued to watch NOAH, and Hiroshi recalls that he had much to criticize, but praised little save for Kenta Kobashi. Still, Kimura never lost his love for wrestling. His last public appearance was at Misawa’s private funeral, which Hiroshi had insisted he come to. None of NOAH’s talent had been able to visit Rusher due to Oyagi keeping his location private, but all of them, as well as other attendees, were glad to see Kimura again. He would admit afterwards that it had been a good thing that he had come. Eleven months later, on May 24, 2010, Masao Kimura died of pneumonia and diabetic complications. Notes The title of this last part is a quote from Kimura’s postmatch promo to Baba on June 1, 1991, which saw Baba’s return to the ring after the 1990 RWTL injury. For the rest of his career, this quote was featured in Rusher's profile in the annual directory issues of Weekly Pro Wrestling.

- 3 replies

-

- jwa

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

- (and 6 more)

-

UPDATES, AUGUST 2022 I began my first Deluxe Profile for Rusher Kimura. I have released three of the four parts I plan to write for him. Part Four will be worked on in September, although I intend to shift my focus back to transcribing resources for personal research rather than writing these profiles, at least for the time being. New Profiles Rusher Kimura (Wrestler, JWA/Tokyo Pro/IWE/NJPW/AJPW/NOAH)

-

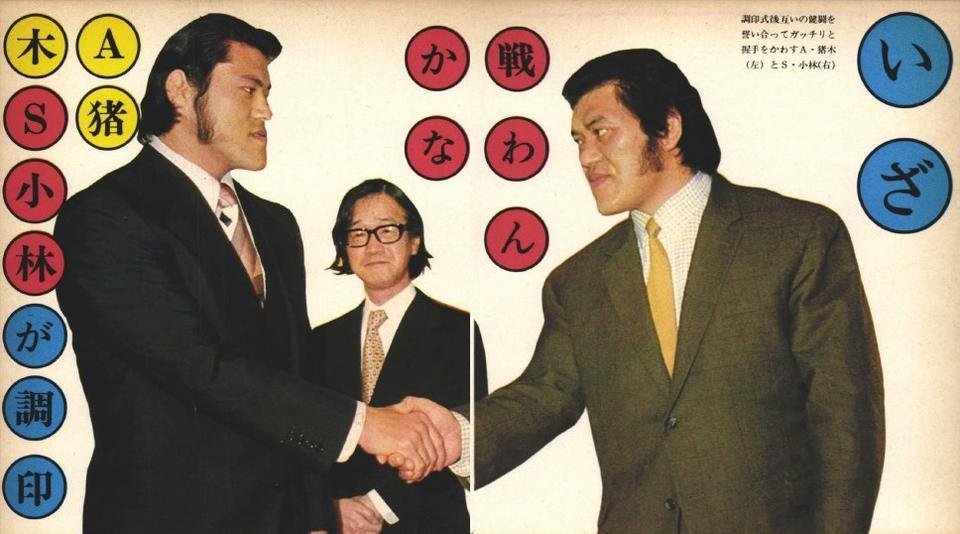

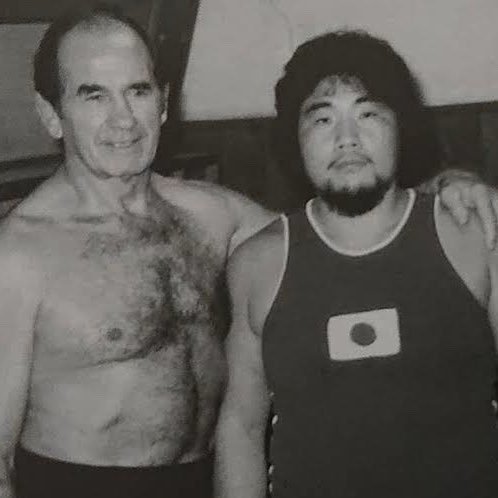

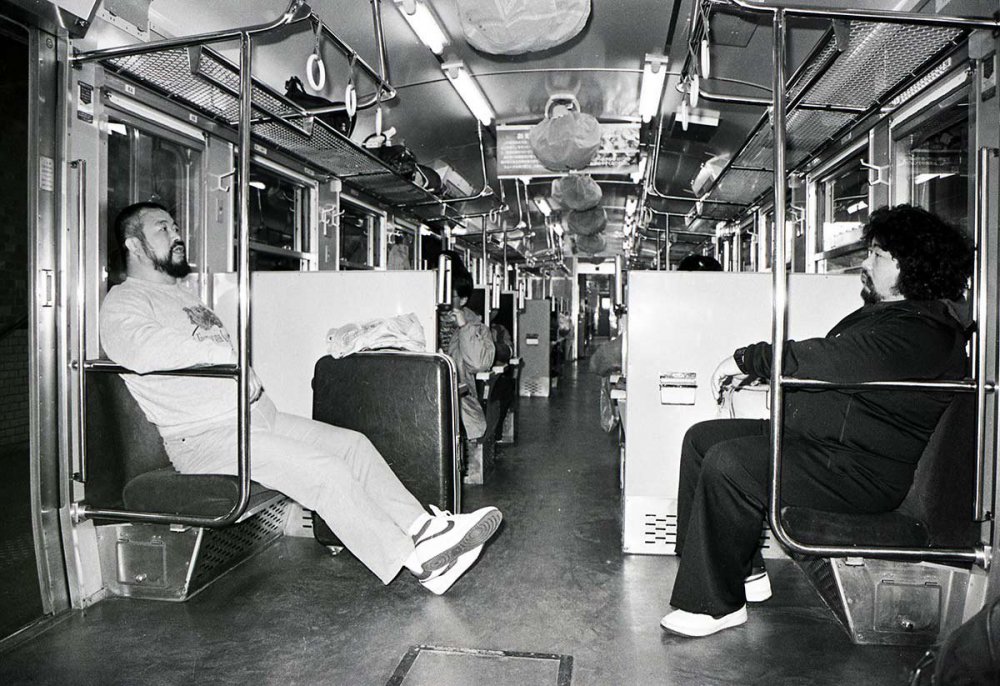

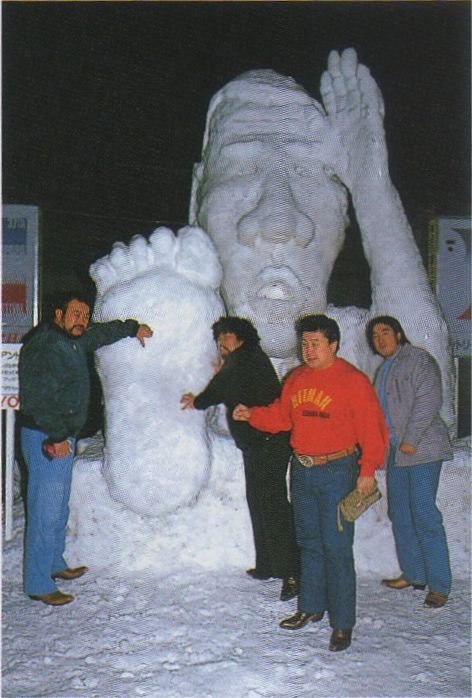

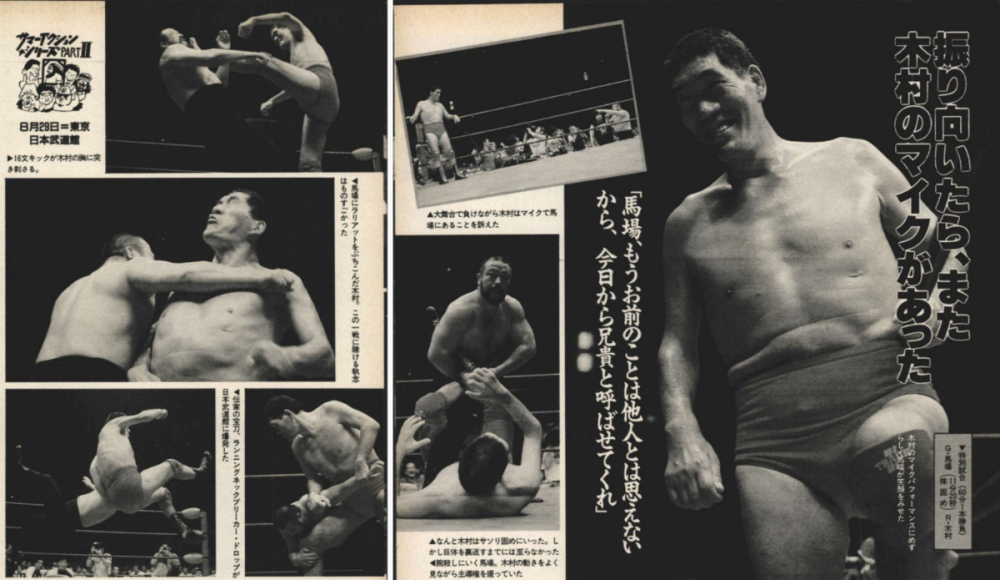

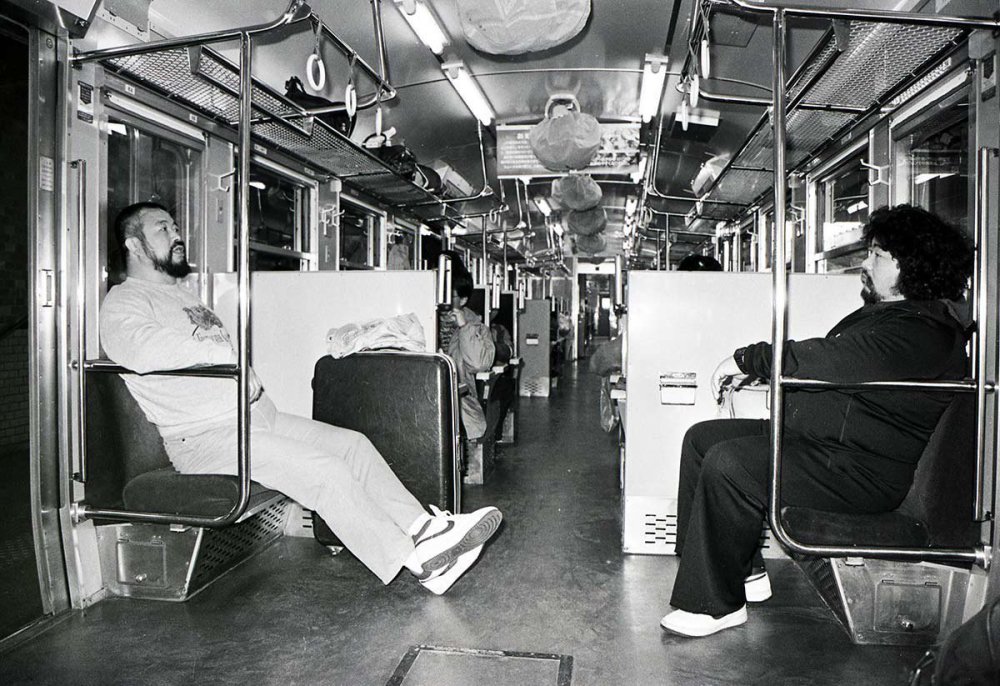

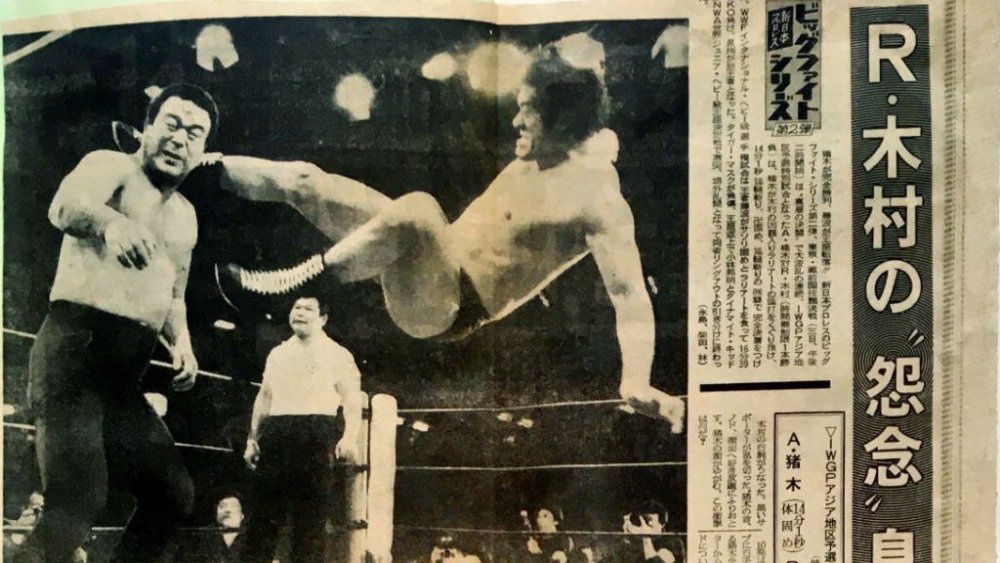

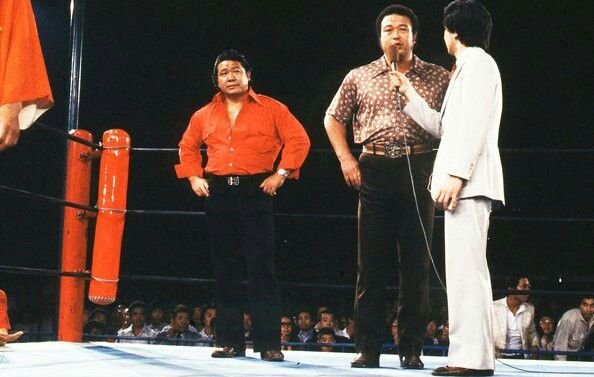

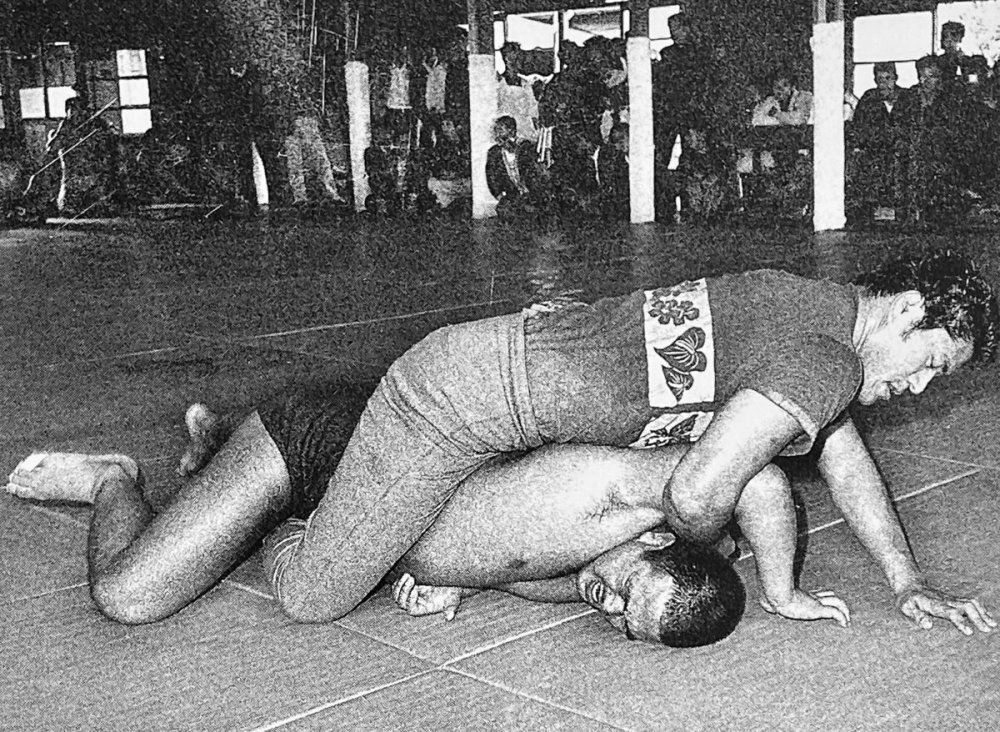

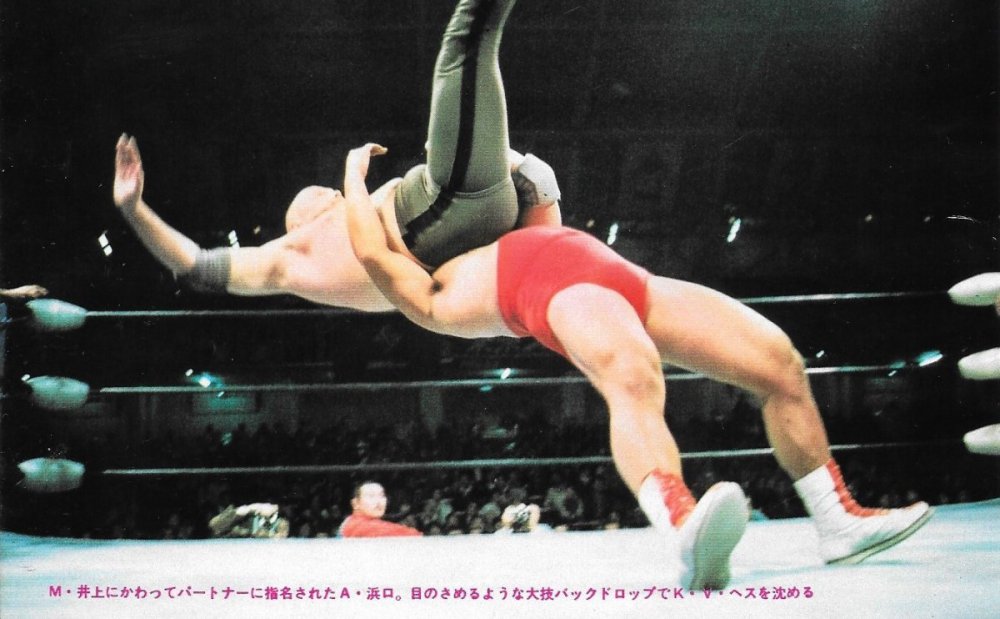

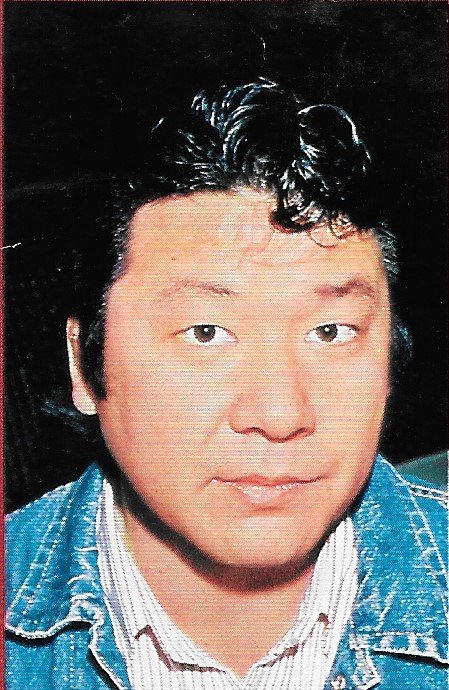

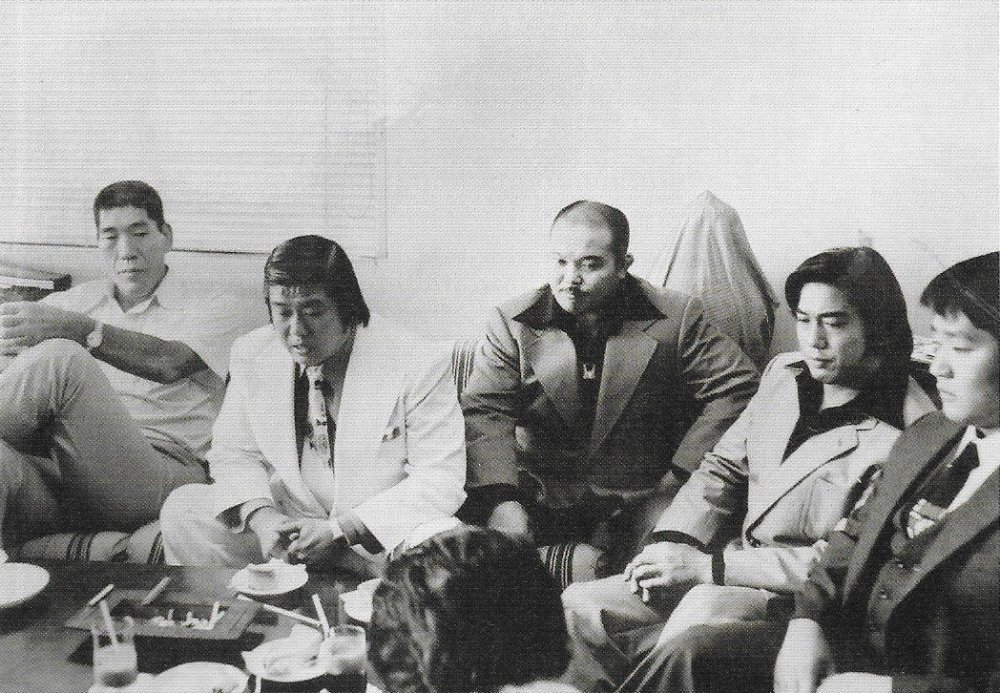

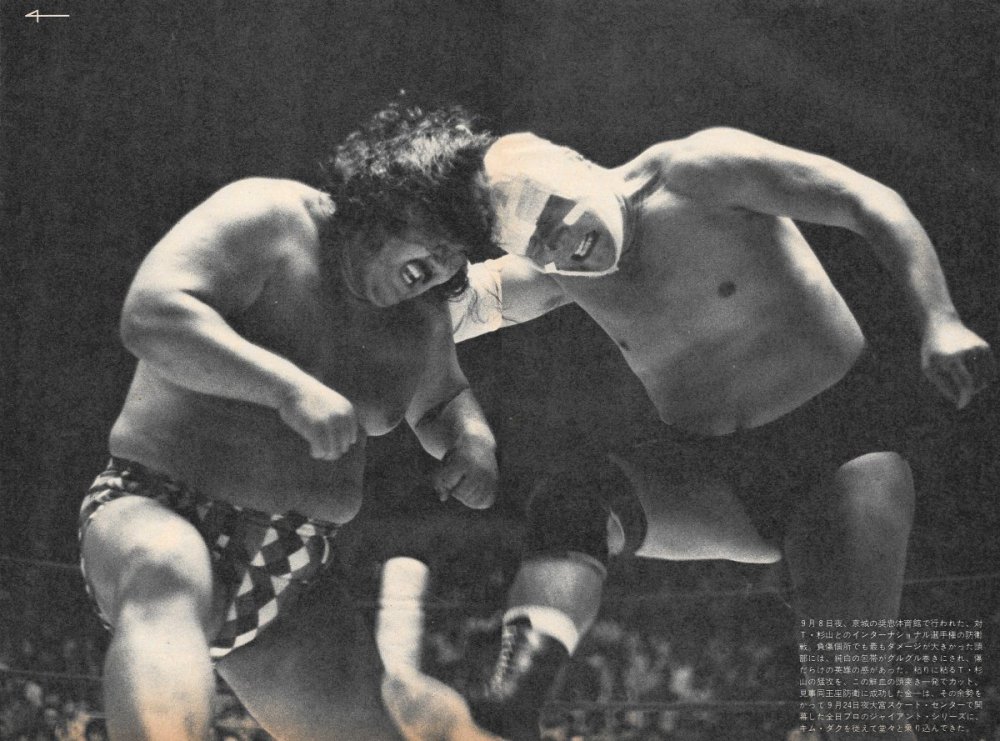

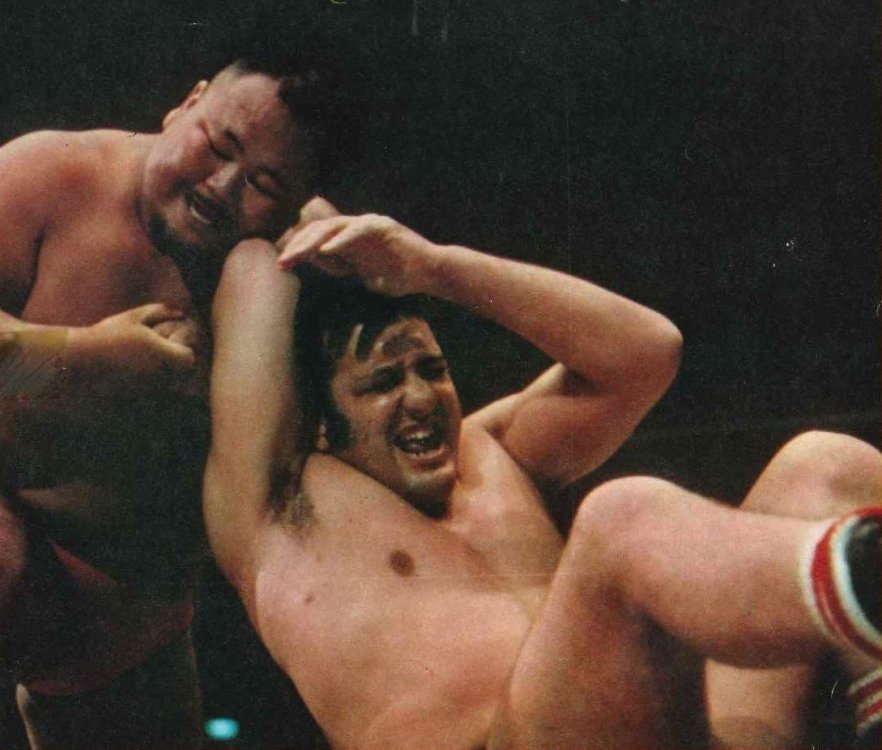

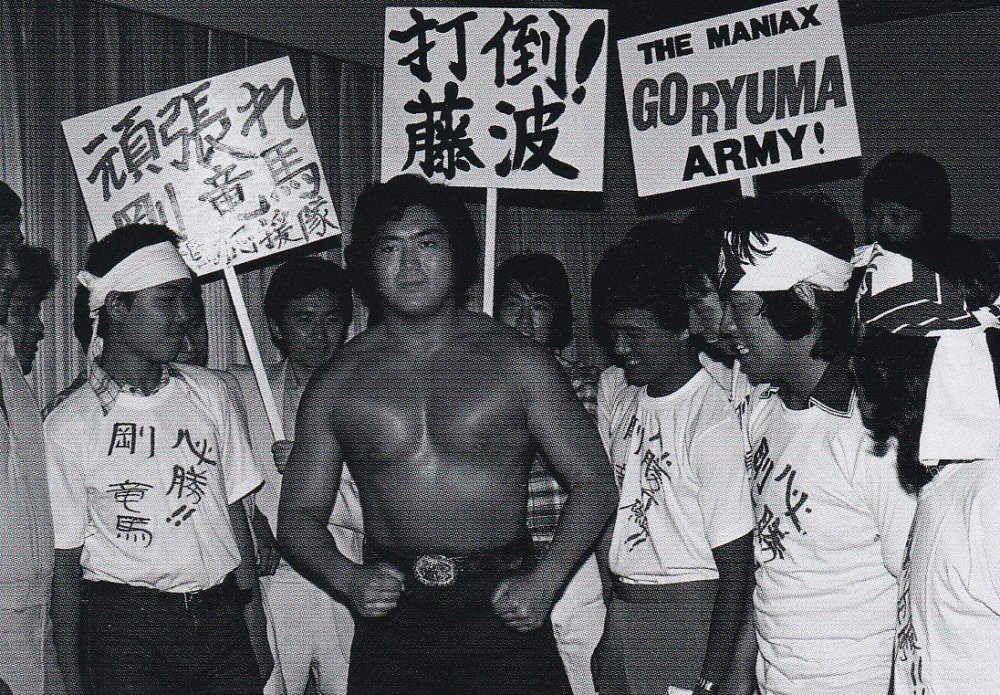

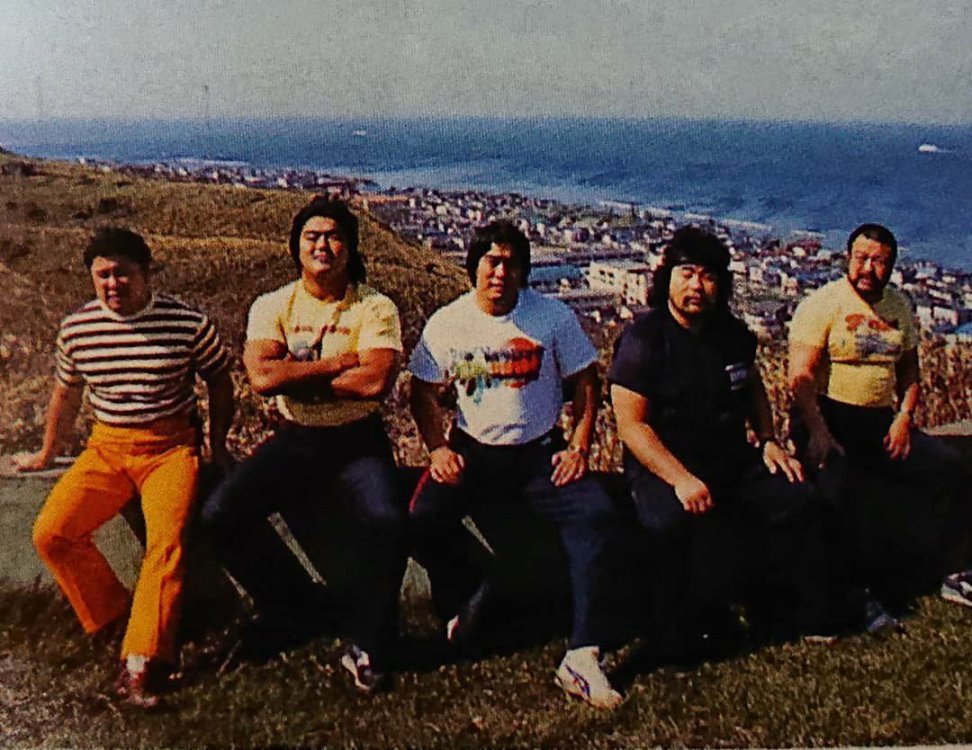

PART THREE: THE BIRTH OF THE BARKING WARRIOR (1981-1988) On September 23, 1981, New Japan Pro-Wrestling ran the Denen Coliseum in Tokyo. Overflowing with an announced attendance of 13,500, the show is most famous in the West for the semi-main event, a clash of the titans between Andre the Giant & Stan Hansen. It was after that match, though, that the next chapter of Rusher Kimura’s story began. Before Antonio Inoki’s match against Kim Duk, Kimura and Animal Hamaguchi came to the ring. A match between Inoki and Kimura was set for October 8 in Kuramae, six years after Kimura had challenged Inoki. When announcer Masaki Hosaka asked Kimura for a comment, Rusher’s first word was a polite “good evening” (konbanwa). Animal Hamaguchi would salvage the segment, cutting a terse, aggressive promo that saw him provoke IWE traitor Ryuma Go at ringside. But the taciturn ace’s gaffe drew laughter from the crowd, and even became something of a meme in its day, turning into a Beat Takeshi joke. Hamaguchi would later say that it was the first time that Rusher had spoken to the fans from his heart. Kimura would not lean into cutting promos for several more years, but this would be the point on which his whole career pivoted. (This promo is featured in the intro for Inoki and Kimura's first match on NJPW World.) Kokusai Gundan trains. After Kimura, Hamaguchi, and Teranishi stormed the NJPW dojo on October 2 to stoke the hype, Rusher got his match. He was not only accompanied by the aforementioned two, but by Strong Kobayashi. Kimura claimed that he had developed a “liver-breaking buffalo strike” as a counter for the enzuigiri, but he never got the chance to use it. The match ended in a DQ victory for the invader, as Inoki refused to recognize a rope break on his armbar. This gave the Kokusai alumni a 2-1 victory over New Japan on the show, as despite Teranishi’s loss to Tatsumi Fujinami, Hamaguchi defeated Go in his match. The corresponding episode of NJPW program World Pro-Wrestling drew a 20.5% rating. On November 5, Kimura wrestled Inoki again, this time in a heated lumberjack match. Inoki got the arm again, and Hamaguchi threw in the towel. After this, the Kokusai Gundan faction began regular work in New Japan. Kimura’s salary, which was “a different order of magnitude” from his Kokusai days, was no longer dependent on how many dates he worked. Make no mistake, though, he earned his pay. Over the next year, Kokusai Gundan became the most hated heels in Japan, through angles such as assaulting commentator Ichiro Furutachi and abducting and beating Inoki in the waiting room. (Hiroshi recalled that there were a lot of review meetings, and that since his father never picked up the phone, he himself would talk with Hisashi Shinma or Seiji Sakaguchi about how the latest Kimura-Inoki match went and what to do next.) This had consequences in his personal life. Kimura’s house was egged and repeatedly subject to games of ding, dong, ditch, while Hiroshi remembers that, when they took their dog on walks, passerby would feed him “strange things”. Kimura would later say that the property damage itself had not bothered him as much as its effect on their dog, for whom the stress induced severe alopecia. Kimura takes an Inoki enzuigiri, c. 1983 Kimura and Hamaguchi entered the year-end MSG Tag League together, placing sixth with eighteen points. In spring 1982, Kimura went on a short American excursion for his first dates outside Asia since the 1972 European excursion. In Los Angeles, he and Go enjoyed a brief reign with the NWA Americas Tag Team titles. Upon his return, the second phase of the Inoki-Kimura feud saw a hair vs hair match on September 21. During an outside brawl segment, Hamaguchi cut Inoki’s hair when Kobayashi handed him a pair of scissors. While Inoki won, Teranishi ran into the ring and got Kimura out of the arena before he could receive his punishment. Despite Hisashi Shinma ordering Don Arakawa to cut his hair instead to try to make it up to the fans (which Kotetsu Yamamoto interrupted), Kero Tanaka’s announcement that Kokusai Gundan had disappeared from the locker room led some fans to storm into the room and throw chairs against the door, shattering the glass before being convinced of their absence (and calmed by a speech from Seiji Sakaguchi). The ensuing one million yen’s worth of property damage led the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium to ask New Japan to ban Kimura. The next main event in the venue saw Inoki & Fujinami wrestle Kimura & Hamaguchi the following month, and riot police were deployed. After the New Japan team won, Teranishi came in with scissors in hand, but Inoki snatched them and cut Teranishi’s own hair to the fans’ delight. This led to what would be a pair of three-on-one handicap matches, both of which Inoki lost. However, initial announcements that Kimura would team up with the now-renamed Strong Kongo in the 1982 MSG Tag League would not come to pass due to Kobayashi’s hurt back. Hiroshi recalls that his father never spoke ill of Baba no matter how drunk he got, but that one could not say the same about Inoki. When Inoki and Shinma’s efforts to fundraise for Anton Hi-Cel deducted from the wrestlers’ salaries, Kimura exclaimed, “here we go again”. Nevertheless, Kimura’s stepson considers his New Japan tenure the peak of his career. Kokusai Gundan collapsed in 1983. Hamaguchi left the group due to a trivial error during a six-man tag in April; he held Inoki in place for a Rusher lariat, but Inoki dodged and Hamaguchi took the move, after which he “lunged” at his partner. Hamaguchi would eventually join Riki Choshu’s Ishingun. Teranishi, meanwhile, would align himself with Kuniaki Kobayashi that summer in an attempt to dethrone Tiger Mask. This left Kimura to wrestle alongside foreign heels such as Abdullah the Butcher and Bad News Allen, as well as do the job to Inoki in a pair of singles matches on the Bloody Fight Series, the first NJPW tour after the infamous coup had begun. Kimura's second excursion of the 80s followed thereafter, as he worked a few dates in Stampede Wrestling. An illustration of Kimura singing a jinku, drawn for an article in Deluxe Pro Wrestling magazine (January 1980). Kimura worked the first New Japan tour of 1984 but was the first native talent to disappear to join the UWF. The interview with Hiroshi Kimura which I have used as a source, which was printed in a 2018 issue of G Spirits, mentions a rumor that Rusher’s transfer to the UWF was by Inoki’s choice. Hiroshi admits he doesn’t know, but that “there were signs he was going to move to the UWF no matter what,” between the ending of the Inoki program and NJPW’s talent surplus. Alongside fellow IWE alumnus Ryuma Go, Kimura worked the UWF’s first shows in April. After this, they went to work for Stampede that spring. During a match against Bad News Allen, Kimura’s throat was crushed by a lariat. Hiroshi’s recollection that his father had had a singing voice “like Frank Nagai” might seem inflated by sentiment, but Rusher’s skill at karaoke had been contemporaneously reported on. It had even been tradition in the IWE for Kimura to start the first show of each year by singing a jinku (traditional sumo folk song). As Haruka Eigen and Joe Higuchi confirmed to Hiroshi after the autopsy, his larynx never fully healed. But the croak of a voice that resulted would be a crucial component of the entertainer that Rusher Kimura became. Kimura and Go continued to work for the UWF through early September, with Rusher going undefeated. They both would leave in the autumn. Go had used his connections to book foreign talent, but the men he brought were incompatible with the martial-arts direction that the promotion shifted towards after Satoru Sayama's signing. He would quit, and Kimura would follow him. Isao Yoshiwara, who was hired as an advisor to New Japan in the middle of the year, attempted to court his old employee for a return. But then, Giant Baba himself invited Kimura to dinner. It was the fifth transfer of Rusher's career. It was the first that he made of his own volition. Kimura was announced as Giant Baba's "mystery partner" in the 1984 Real World Tag League. With just two points, they were already sure to be Baba's worst-performing team in the annual tournament when they faced Jumbo Tsuruta and Genichiro Tenryu on December 8. But during that match, Kimura turned on Baba when Go came up to the apron. Striking his partner with a lariat, Kimura’s team broke up then and there, with Go and Goro Tsurumi at ringside. Kokusai Ketsumeigun poses with a sculpture of Giant Baba at the Sapporo Snow Festival, and makes their feelings known. The true plan for Kimura took shape. Kokusai Ketsumeigun featured most of All Japan's ex-IWE talent, from Tsurumi (who would wave a Japanese flag in their entrances, a sight reminiscent of Fabulous Freebird Michael Hayes' contemporaneous use of the Confederate flag) to Apollo Sugawara and Masahiko Takasugi. When Ashura Hara returned to the company as a heel that year, he would work alongside the faction without ever fully joining it. Even Tiger Jeet Singh worked with them as something of an honorary member. Rusher’s highest-profile match from this period was on June 21, 1985, when he challenged for Baba’s PWF Heavyweight title in the main event of the Special Wars in Budokan show. This match, which happened eleven days after Yoshiwara’s death from cancer, was the last successful defense of Baba’s last championship reign, as he dropped the belt to Stan Hansen the following month. Kimura entered the 1985 RWTL with Hara, where the team scored five points in a three-way tie for last place. Overall, though, the second incarnation of Kimura's ex-IWE heel stable was far less impactful than the first. You may know that December 8, 1984 was also the date that the trigger was pulled on Japan Pro Wrestling's working arrangement with All Japan, as Riki Choshu, former Kokusai Gundan member Animal Hamaguchi, and a baker's dozen more stormed the ring at the end of the show. Kokusai Ketsumeigun could not compete with the allure of proper AJPW vs. (ex-)NJPW matchups. In fact, Japan Pro would severely damage the faction. In late 1985, the Calgary Hurricanes unsuccessfully attempted to leave NJPW and join Japan Pro. Choshu had not wanted them. He had envisioned Japan Pro as an independent organization that would work with other promotions on a tour-to-tour basis, so he saw potential for future cooperation with his former employer and did not want to further damage their relationship. Then, Baba & Inoki signed an agreement at Rikidozan's grave that winter to not swipe talent from each other. Nevertheless, the trio of Super Strong Machine, Hiro Saito, and Shunji Takano joined Japan Pro at the end of the fiscal year. This was a mortal wound, as Go, Sugawara, and Takasugi, alongside referee Mr. Hayashi, all fell victim to budget cuts. Hiroshi remembers that his father was devastated. Even with the reliable support of Tsurumi, Kimura struggled to make television afterward, while Hara started working more with the Hurricanes. Another singles match against Baba in the Budokan happened in June 1986, but tellingly, it was not the main event. Kimura and Tsurumi ride the train to their next match, due to the overcapacity of the foreign tour bus. (c. March 1988) Gradually, Kimura found his voice in All Japan, and I mean that literally. Kimura’s television appearances began to make time for his postmatch turns on the microphone. The earliest example I could find of the Rusher “microphone performance” in the proper sense (that is, which drew laughter from the audience) was from a February 1987 show in Korakuen Hall. I was able to match a couple of captioned early Rusher promos from a compilation in a 1991 television segment to transcripts on his Japanese Wikipedia page. In one (at 0:51), Kimura blamed his loss to Baba on his failure to eat fifteen pieces of yakiniku, before vowing to eat twenty and “beat the son of a bitch”. Hiroshi admits that the Rusher Kimura of old was gone by this time, but the character that emerged during this time was much closer to who his father actually was, at least when he’d had a little to drink. His son expresses pride that he was not just a “salaryman wrestler”. On August 29, 1988, Kimura and Baba wrestled one last singles match. After his loss, he took the microphone and asked that Baba let him call him his older brother. In his promos, Kimura would call Baba aniki from that day forward. Referee Kyohei Wada recalled that “the Budokan went boom”, totally embracing Rusher’s face turn. That year, Kimura and Baba joined forces for the Real World Tag League. Far from the poor performance and late-term breakup of their previous showing, the team notched a decent 13 points. Weekly Pro Wrestling coverage of Kimura and Baba’s final singles match. [Issue #276; 9/14/1988]

- 3 replies

-

- jwa

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

- (and 6 more)

-

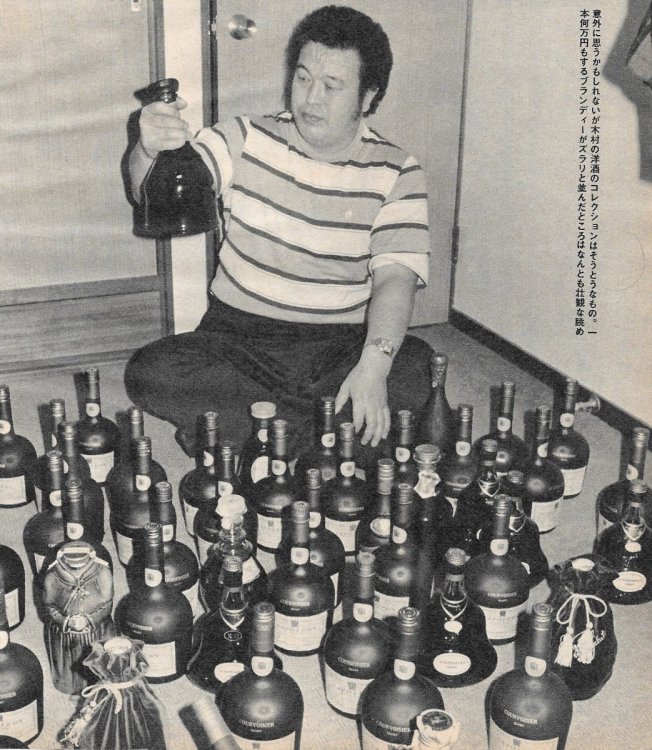

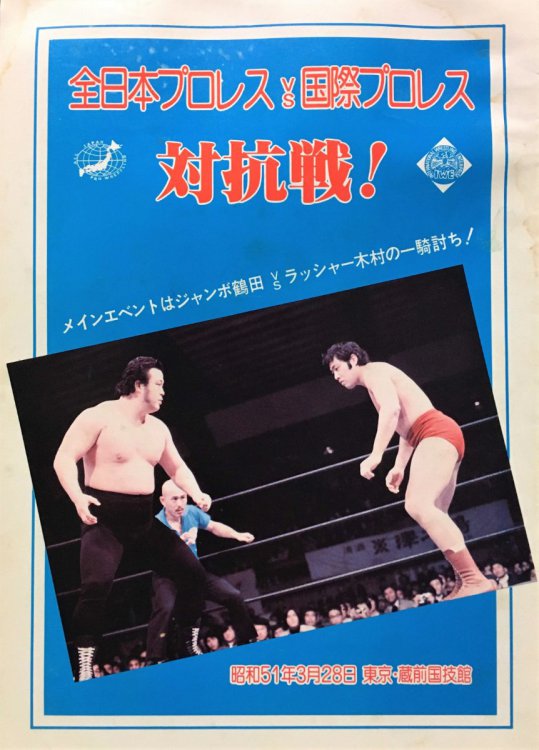

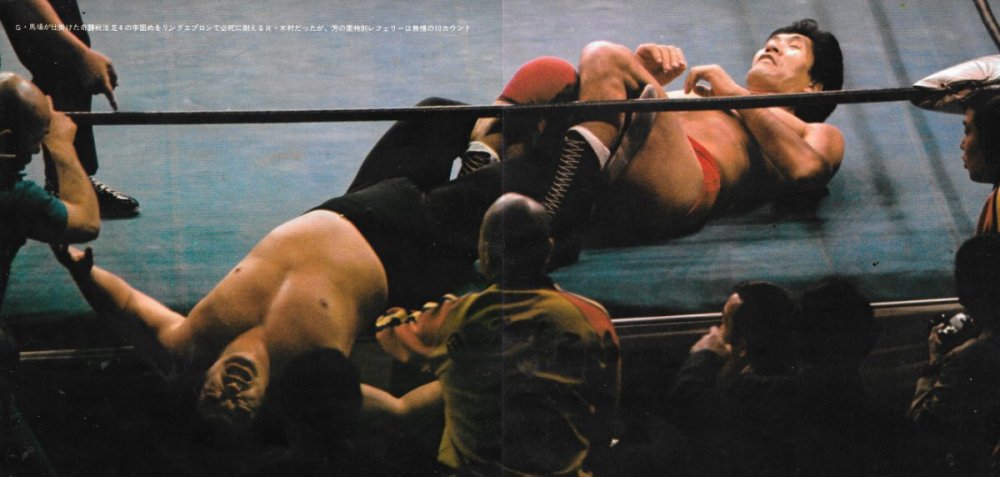

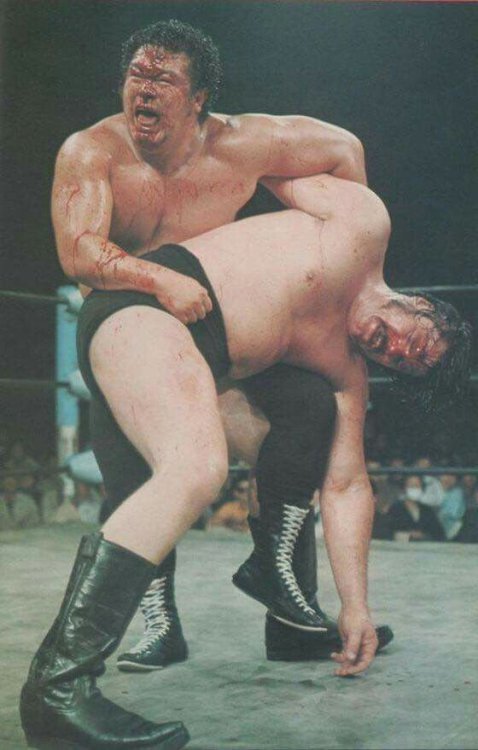

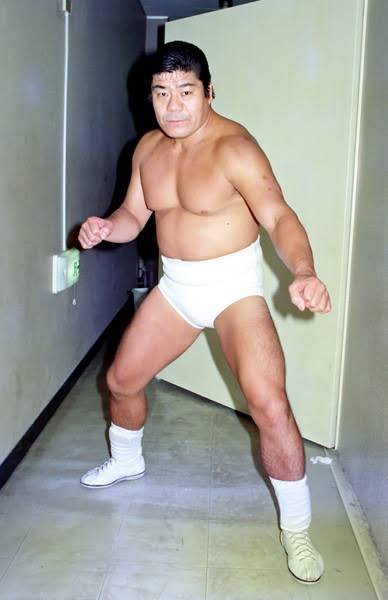

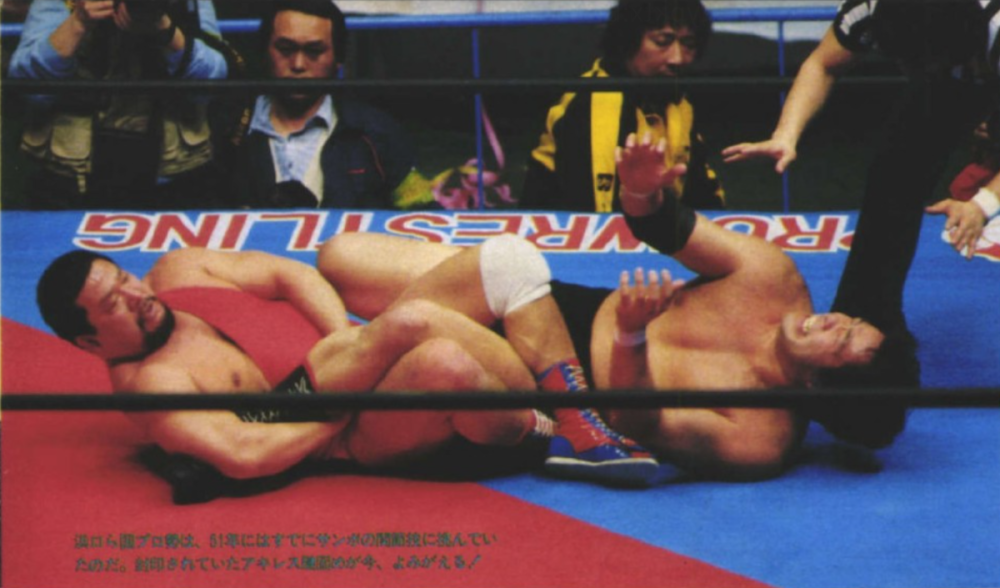

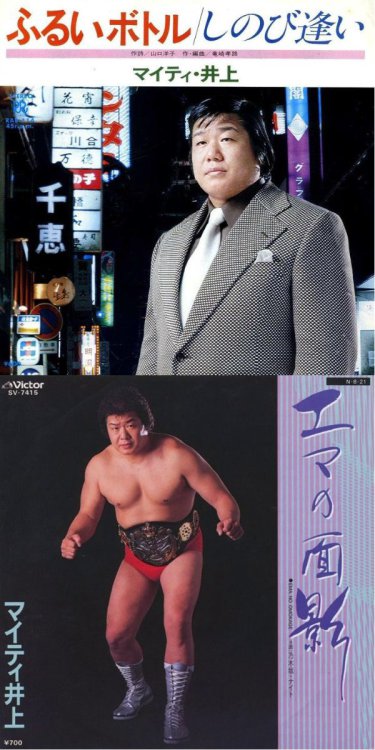

PART TWO: THE TRAGIC ACE (1974-1981) The first tour of 1974 wasn’t especially notable for Rusher. The one piece of interest was a mask vs hair match which he won against masked heel the Jackknife; this turned out to be Oliva Asselin, one of the wrestlers who worked the 1951 Japan tour that had helped establish pro wrestling in the country. Of course, this tour was of great significance to the promotion. On the last day, Strong Kobayashi turned in his notice and relinquished his titles. He had had enough of internal factors within the company which hinged on Kusatsu, who by this point had become Kokusai’s booker. As an analysis in Showa Puroresu notes, Kusatsu had booked himself, Kobayashi, and Kimura in a roughly equal amount of main and semi-main events; due to the company’s incentive structure, this had made all three receive essentially the same amount of bonus pay in the latter half of 1973. This was on top of Kusatsu’s penchant for “sports club style” bullying, which testimonials from the likes of Goro Tsurumi have claimed extended to Kobayashi. Although I have not confirmed whether this would have happened regardless of the ace’s departure, it was also around this time that TBS canceled their deal. After Kobayashi's departure, Kimura was appointed a "wrestler management director". Kokusai then held their first tour in seven years without network support. According to Showa Puroresu, Kokusai had planned to groom Tetsunosuke Daigo as Rusher’s successor in the wire mesh deathmatch. This plan was thrown out the window when, just before he was scheduled to return from Canada, Daigo lost his right leg in an auto accident. This tour would hinge on the kanami stipulation, with ten out of its sixteen main events being held in the cage. It also received support from All Japan Pro Wrestling, as Giant Baba led a crop of talent (Jumbo Tsuruta was overseas at the time) to support the IWE. This saw Kimura team with his future tag partner for the first time. TBS executive Tadao Mori gave Kokusai a lifeline by connecting them to the Tokyo 12 Channel network. The head of its sports department, Tsuyoshi Shiraishi, was hesitant to pick up the IWE, and would only do so on the condition that they started a women's division for continuity with T12C’s own experience in joshi broadcasts. The pressure was on Rusher in a pair of one-off television broadcasts, where they had to draw ratings better than the 3% range their last TBS episodes had done to receive the go-ahead from T12C. On May 26, Kimura and Kusatsu squared off in a #1 contendership match for the IWA World Heavyweight title, which would be decided in a June 3 match against Billy Robinson. Isao Yoshiwara had suggested in an interview with Monthly Pro Wrestling that this could be “even more exciting” than the previous year’s Kobayashi-Kimura match. As Showa Puroresu remarks, though, if such a match had been held in the 1950s, it would have started a riot. Official records stated that three thousand attended the Toyota city show, but 8mm footage of the match survives and indicates that this was greatly exaggerated. As the tour’s foreigners watched at ringside, the tag champions wrestled tit-for-tat until Kusatsu hit a vertical suplex. As he went for the cover, Sailor White—who had emerged as a deathmatch adversary against Rusher the previous tour, impressing Baba enough to get booked for the second Champion Carnival, and would wrestle Kimura on June 5 in puroresu’s first chain match—interfered and kicked him in the back. He got away with two more bits of interference against Kusatsu until Robinson had enough and tossed White out of the ring. After that, Rusher got Kusatsu in a Boston crab, to which his partner “easily gave up”. Kimura had been Robinson’s first opponent in Japan. One year later, he had received his first world title shot against the great Brit. Earlier in this tour, a double countout had been the best result Rusher had ever earned against Robinson. Now, he would challenge him in Korakuen Hall on live television. The match was refereed by Hawaii promoter Ed Lewis and was the customary two-out-of-three-falls. Rusher won the first fall with his crab, but the second fall saw him struggle to finish Robinson off, and Billy hit his signature one-handed backbreaker and a butterfly suplex to even the score. “Lunging at Kimura in the corner” as soon as the bell rang, Robinson attacked his lower back until he finished him off with another butterfly. Kimura had lost what would be his final singles match against Robinson; in a year-end interview with Monthly Gong, Yoshiwara expressed disappointment in who he thought would be Kokusai’s “ace in the hole”, remarking that Rusher’s “passive personality had come out in the match”. However, the 6.4 drawn by the match saved the company, even if broadcast footage has not survived. T12C continued to test the waters with one-off broadcasts until Kokusai began regular programming that autumn. By the time that they had, Rusher was no longer pegged as the company ace. The network had thrown their support behind the flashier Mighty Inoue, and both Yoshiwara and Shiraishi had ultimately agreed to push him. When the IWA world title came back around the waist of Superstar Billy Graham, it took Inoue all three of his title shots to bring the belt home, but he pulled it off. The final IWE tour of 1974 would turn out to be a grand finale for their four-year partnership with the AWA, as the company would opt in early 1975 to save money and use Tetsunosuke Daigo to book talent for them instead. While Inoue wrestled a double world title match against Verne Gagne, Kimura & Kusatsu got two shots at AWA tag champions Nick Bockwinkel & Ray Stevens, one of which was a double title match. In both cases, they went to DQ finishes. The Inoue experiment ended on the following tour with his title loss to Mad Dog Vachon. This set up a switcheroo, where Kimura became the ace while Inoue became tag champion alongside Kusatsu. Throughout the tour, Vachon and Kimura squared off in three wire-mesh deathmatches at Vachon’s request. In between the second and third, Vachon won the IWA world title from Inoue by luring him out into a double countout after having won the first fall. He accepted the proposal to make his last match against Rusher a title defense. The match that would cement Kimura as the third and last of Kokusai’s major aces happened in a packed house. Sapporo’s Nakajima Sports Center drew an announced crowd of 7,500. The Mad Dog bloodied the challenger with a bottle opener, but the demon of the cage returned in kind. The finish was a flurry of Rusher offense, with three piledrivers and a Rusher suplex setting up a crab, and a submission, in 7:25. Kimura makes Vachon submit to begin his first IWA title reign. Kimura would stand tall as Kokusai’s ace for the rest of its life. He won the world title five times, sure, but all of his losses were quick transitional reigns to get top opponents over before a switchback at the end of the tour. However, Rusher's temperament was not natural for the face of a wrestling promotion. An article in Tokyo Sports recounts a night when Yoshiwara took Kimura out for drinks, in an attempt to coach him to be more outgoing. The two downed four bottles of sake, but they would only exchange a few words of thanks. In another apocryphal instance, Dory Funk Jr. had assumed Kimura was mute during their work together in Kansas and was reportedly shocked to hear him speak when the two crossed paths again in the 1975 Open League. Despite his quiet nature, Showa Puroresu notes that Kimura’s first title win brought on a drastic increase in attendance for a few months, although it acknowledges that this could have been due to other factors. Kimura & Kusatsu, the KK duo, vacated the IWA World Tag Team titles after eleven successful defenses. This record would be matched once more by Inoue & Animal Hamaguchi's first tag title reign. While Mighty Inoue would admit much later that he had been relieved to no longer shoulder the burden of being the company’s top champion, at the time he remained in the title picture. Over the next three years, Inoue received a series of title shots against Kimura. While All Japan’s revived All Asia Tag Team titles would begin to make title matches between natives a less rare sight in the late seventies, Kimura’s defenses against Inoue were still remarkable, and it is a great shame that none of these matches survive in anything more than fragmentary form. For his first tour as ace, Kimura defended his title against the Japan-debuting Killer Tor Kamata, with whom he had tagged during his American excursion half a decade before. Meanwhile, on June 6, Rusher held a press conference where he challenged Antonio Inoki. Inoki had called for a unified commission to determine Japan’s true champion for years, which had led Giant Baba to arrange a brief NWA title switch with Jack Brisco behind the Alliance’s back to save face after consistently dodging Inoki’s challenges. Kimura appealed to Inoki’s efforts to get this match in stating this challenge. Furthermore, he made it clear that, “unlike the ingrate Strong Kobayashi”, Kimura would challenge him as a representative of Kokusai. Five days later, Inoki’s own conference saw him dodge questions on Kimura as he stated his challenge to Muhammad Ali. However, the IWE office received a letter from Inoki which thoroughly dressed Kimura down. Inoki chided him for his presumptuousness, telling his former Tokyo Pro coworker to “know thyself”. He would only accept Kimura’s challenge if he defeated Baba, and if that were to happen, New Japan would host the match. On June 25, Kimura presented his own written reply. Stating that he interpreted Inoki’s response as an evasion of his challenge, Rusher declared that “sportsmen do not fight with their lips and tongues”, and that he would leave the verbal battles to Inoki and Ali. A furious Inoki made a statement printed in the August issue of Monthly Gong. He ridiculed the implication that the IWE sought a joint show with New Japan, as NJPW could fill up the Kuramae Kokugikan, while Kokusai could only sell out Korakuen Hall. He stated frankly that he believed that Kimura was not only inferior to himself, but even to Kotetsu Yamamoto and Kantaro Hoshino. If Kimura had really wanted to challenge him, and not just drum up publicity by calling him out, then Kokusai would accept the challenge on a New Japan show if it meant that Kimura could beat Inoki. The second half of 1975 saw Kimura wrestle his first matches against Gypsy Joe, who would become the IWE’s definitive gaikokujin in the latter half of its life. Alongside Kusatsu and Inoue, Kimura was one of three Kokusai entrants in the AJPW-hosted Open League tournament. Rusher ended the convoluted tournament with six points, defeating Ken Mantell, Baron von Raschke, and Don Leo Jonathan, but losing to Giant Baba and Dory Funk Jr. and going to double countouts with Jumbo Tsuruta, Abdullah the Butcher, and Dick Murdoch. The program for the 3/28/76 AJPW vs IWE show, featuring a photograph of Kimura & Tsuruta's 1975 Open League match. On March 28, 1976, in an AJPW vs IWE show at the Kuramae Kokugikan, Kimura challenged Tsuruta in the second of Tsuruta’s ten-match Trial Series. Refereed by former JWA president Junzo Yoshinosato, who had taken a commentary job with the IWE, the match won Kimura his first and only Tokyo Sports match of the year award. In the leadup to the match, Kimura attended a sambo training camp and received instruction from Victor Koga. Kimura wouldn’t utilize sambo much in his wrestling, but he busted out an armbar against Jumbo, and incorporated it into his training regimen. The match would end in a draw after Tsuruta’s bridging German suplex in the third fall was counted as a double pin. It was a finish which would be used again for one of Jumbo’s early-80s classics against Ric Flair, but more pertinent to this story, it was a finish that revealed how far Yoshiwara was willing to bend to do business. The next month, Kimura’s first world title reign ended after eleven successful defenses, against the Undertaker: Hans Schrober, that is. Kimura vacated the title of his own volition as, after he won the first fall, the double countout in the second fall had given him a tainted victory. Of course, Rusher won a rematch in the cage. The Undertaker would be greatly overshadowed by Rusher’s next challenger. After leaving AJPW in October 1973, Umanosuke Ueda had chosen to wait out his three-year contract with Nippon TV while he lived and worked in the States. On New Year’s Day 1976, Ueda issued challenges to Baba and Inoki, but both were disinterested. At Yoshinosato’s suggestion, Ueda talked with Yoshiwara, and he would return to Japan for the Big Challenge Series tour. On June 7, Kimura lost his world title to Ueda, who took advantage of a ref bump to down Rusher with a foreign object for the pinfall. This title change cemented the Speckled Wolf as the first native heel to truly get over in Japan. As would soon became apparent, though, Ueda was less interested in doing business with Kokusai than with using their top championship as a point of leverage to get a match with Inoki. When he restated his challenge on the day of the Inoki's fight against Muhammad Ali, NJPW sales head Hisashi Shinma was interested, and a match against Strong Kobayashi was scheduled for August. On Kokusai’s next tour, Ueda lost the belt without doing a job. During a wire mesh deathmatch against Kimura, which was untelevised, he knocked out referee Osamu Abe, and a no-contest finish ensued as Inoue and the Super Assassin both climbed the cage. A left shoulder injury, which Mighty Inoue insists was fabricated, kept Ueda from having to give Rusher his heat back, and Rusher won the vacant belt at the end of the tour against the Super Assassin. This third reign would be Kimura’s longest, as three years passed before the belt escaped his clutches again. Kimura’s last title match against Tor Kamata took place in June 1977. In spring 1977, the IWA World Series was revived for a sixth and final iteration. Kimura would win it against Mad Dog Vachon, but the tournament was also interesting for his matches against Kusatsu and Big John Quinn. On that same tour, he participated in a tournament for the vacant IWA tag titles, but he and Katsuzo Oiyama lost in the first round to tournament winners Quinn & Kurt Von Hess. The following tour saw Kimura defend for the final time against Tor Kamata, whose challenge was supposedly made by way of a cassette tape sent to the IWE office. This tour, which also saw Kimura win a tournament held across twelve dates in Hokkaido, would be Kamata’s last for Kokusai before he began work for AJPW the following year. The most interesting thing to happen this year was a KK duo reunion, as Kimura & Kusatsu entered AJPW’s first Real World Tag League. Their eight points tied them for fourth place with Kintaro Oki & Kim Duk and matches against that team as well as Baba & Tsuruta were broadcast on NTV. The infamous countout finish of Kimura & Baba’s February 1978 match. In February 1978, the IWE, AJPW, and Kintaro Oki’s Korean promotion Kim Il competed against each other in a short joint tour. Starting at Kuramae on February 18, the tour’s first main event was Kimura and Giant Baba’s first singles match since the 1975 Open League. Refereed by Yoshinosato, the match saw Kimura lose in infamous fashion. While trapped in a figure-four, Kimura attempted to roll them out of the ring, but only managed to roll himself out far enough to get counted out as he hung from the apron. It is plausible that Yoshinosato himself had suggested this finish, as it replicated that of one of the JWA's last major matches; this was how Kintaro Oki (and Ueda) had lost the NWA International Tag Team titles to Fritz von Erich (and Killer Karl Krupp). Three days later in Osaka, Kimura wrestled Jumbo Tsuruta and got himself disqualified. Finally, the KK duo reunited once more in Gifu to challenge Oki & Kim Duk for the NWA International Tag Team titles, against whom they went to a draw. In 2018, IWE television producer Masakazu Tanaka held a talk at wrestling store Toudoukan and made revealing comments on the matter of the company’s interpromotional matches. Unlike AJPW and NJPW, IWE’s contracts in the Tokyo 12 Channel era did not have network exclusivity clauses, which gave its talent freedom to appear on other promotions. According to Tanaka, Yoshiwara was not concerned about how his talent were booked, as he believed that “the content was more important than the result”. These interpromotional matches became an important part of Kokusai’s cash flow, due to NTV (and then TV Asahi’s) superior broadcast fees. This desperate attitude only deepened Kokusai’s perception as puroresu’s minor league. The IWE burned their bridge with All Japan in spectacular fashion near the end of the year, when they counterprogrammed New Japan’s Pre-Japanese League tournament with the Japan League. Despite the fact that this tournament, which Kimura won, featured AJPW talent, the tour’s climactic show at Kuramae featured NJPW’s Kuniaki and Strong Kobayashi in undercard matches. Behind the scenes, Yoshiwara had been angling for a partnership with New Japan, and had even offered Hisashi Shinma his position as iWE president. They would reach a deal with NJPW, but it was even less in their favor than their dealings with All Japan. Shinma was not able to help Kokusai as much as he intended due to opposition from the likes of NJPW sales head Naoki Otsuka. The highest-profile matches that Rusher got out of it were a pair against Strong Kobayashi, which he won. The first of these was at the Tokyo Sports show of August 26, 1979, which he won by countout. It was revealed decades later that Yoshiwara had been hesitant to go through with this first match, and it was not a good showing. The second occurred on New Japan turf in December 1980 and was an IWA title defense. Neither match was properly televised, although the Tokyo Sports match, which was given limited (now lost) coverage in a news program, circulates as part of an eighty-minute audience recording. Kimura poses with his liquor collection, c. early 1979. Hiroshi Kimura moved back to France in 1979, where he would send money back to Kimura and his mother. Meanwhile, Yoshiwara mortgaged his house to help his wrestlers, including Rusher, make ends meet. Tokyo 12 Channel opened their pocketbooks to try to stimulate the company. They hired the likes of Lou Thesz and Kintaro Oki, the latter of whom was essentially pushed as a parallel ace to Rusher for much of 1980. They also made it possible for Kokusai to book the AWA’s Verne Gagne and Nick Bockwinkel. It was against Verne that Kimura lost and then regained his IWA world title for the final time in November 1979. (Kimura’s third reign had ended a few months earlier to put over Alexis Smirnoff before regaining the title.) The previous month, he and Bockwinkel had wrestled an AWA/IWA double world title match. However, Yoshiwara’s unwillingness to provide T12C a budgetary breakdown and continually dismal television ratings led the network to cancel these supplemental seasonal budgets, which put the kibosh on a planned Baron von Raschke program. Ultimately, it would help cause the network to cancel International Pro Wrestling Hour itself. Contemporaneous interviews indicate that Kimura felt responsible for Kokusai’s decline in attendance and television ratings. Showa Puroresu writes frankly that his lower body was “noticeably deteriorating”, and that he sometimes “wobbled” when performing a chop. The title of this part of the profile, The Tragic Ace, is inspired by Showa Puroresu writer Dr. Mick’s coinage of Higeki no Tōshō (tragic fighter), which he felt was a more appropriate nickname for Kimura’s ace run than his old kanami no oni moniker. In the IWE’s last year, as Kusatsu decided to concentrate fully on sales work after an ankle injury, Yoshiwara became the company’s booker. Kimura would consult with him on the matter, and according to a 2019 book by Koji Miyamoto, Rusher himself booked the undercard matches on provincial shows. In spring 1981, Tokyo 12 Channel canceled International Pro Wrestling Hour, reducing Kokusai’s television presence to a handful of single broadcasts across the ensuing months. Negotiations with AJW broadcaster Fuji Television may have saved the company, but the network canceled talks due to wrestling’s “bad image” after the first shots in AJPW and NJPW’s “pullout war”, in which the two companies swiped foreign talent from each other. Kokusai had been further and further marginalized for years in the cold war between Baba and Inoki, so it was fitting that a conflict between them was what ultimately killed the IWE. Also that spring, the company as a whole and Kimura specifically were devastated by the death of Snake Amami. For Rusher, who had recently mourned the passing of his mother and one of his Akita Inu dogs, the loss was so great that he spent the night at Amami’s wake to sleep with his departed friend. When the IWE roster returned home from their final show, they stopped at what had been his home to light incense. Kimura would decline offers to have another valet for the rest of his career. When the company finally went under in summer, Kimura apologized to his stepson for having been unable to provide for him. According to Hiroshi, Kimura considered retirement to start a business with the help of a patron in Shizuoka, but as Animal Hamaguchi and Isamu Teranishi planned to transfer to New Japan, Rusher decided to follow and help his friends. The IWE's final show took place on the grounds of an elementary school in August 1981.

- 3 replies

-

- jwa

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

- (and 6 more)

-

Part One of my Rusher Kimura profile is now live. Part Two, which will cover the rest of Kimura's IWE tenure, is probably about 65% done.

-

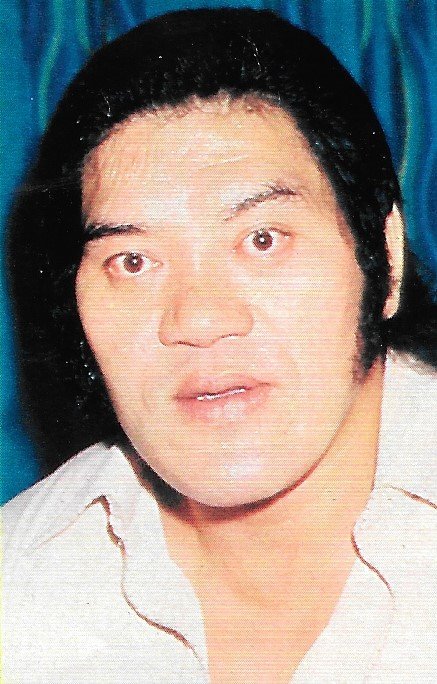

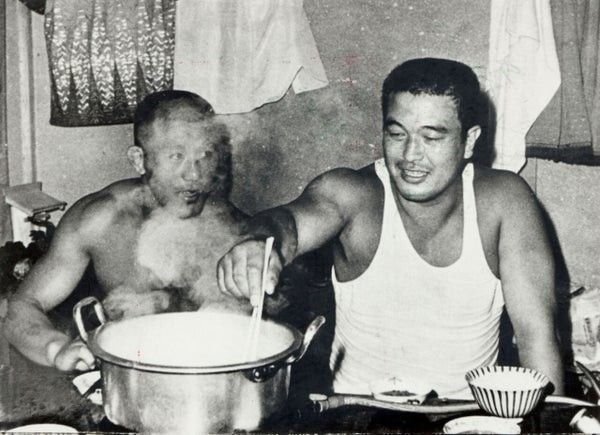

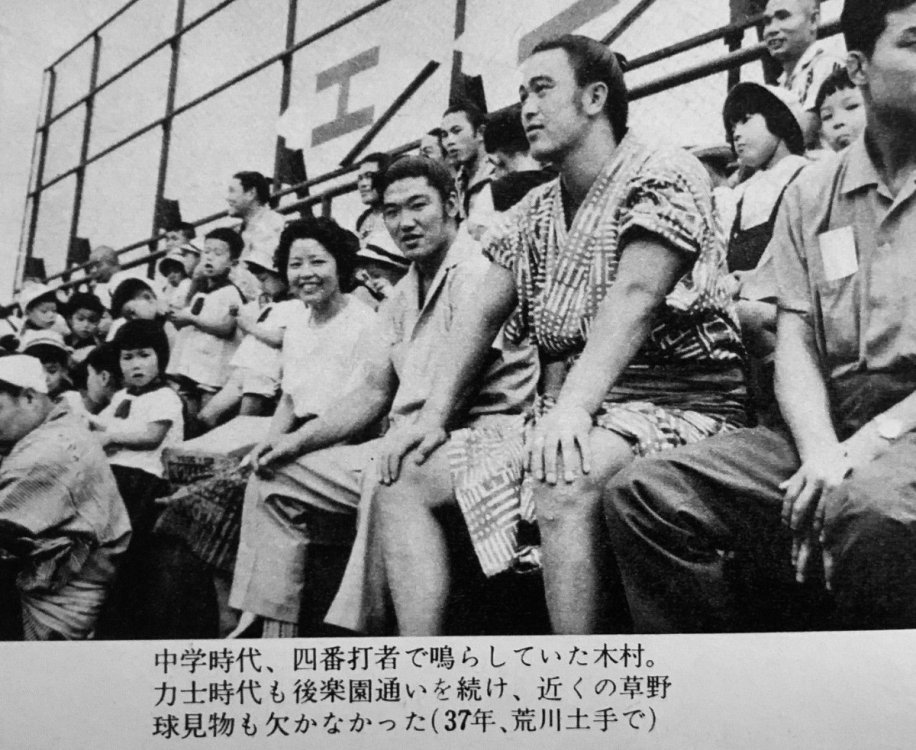

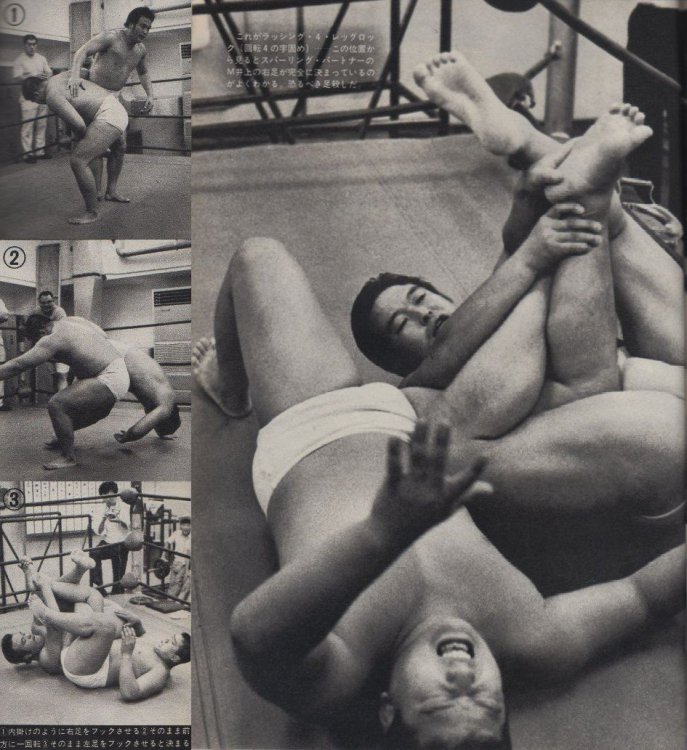

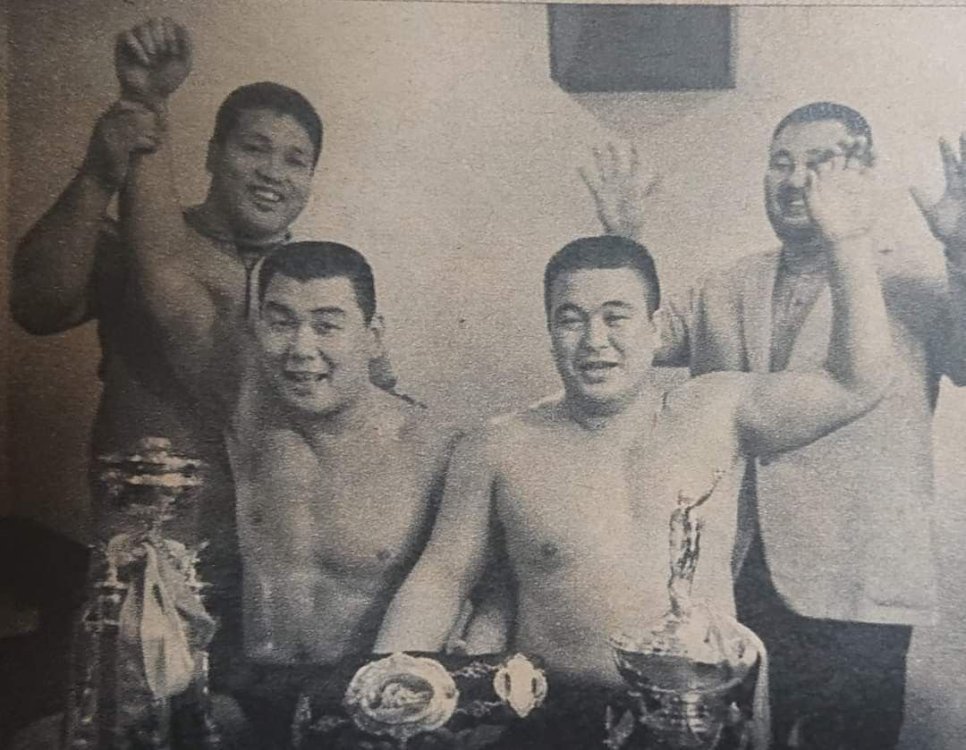

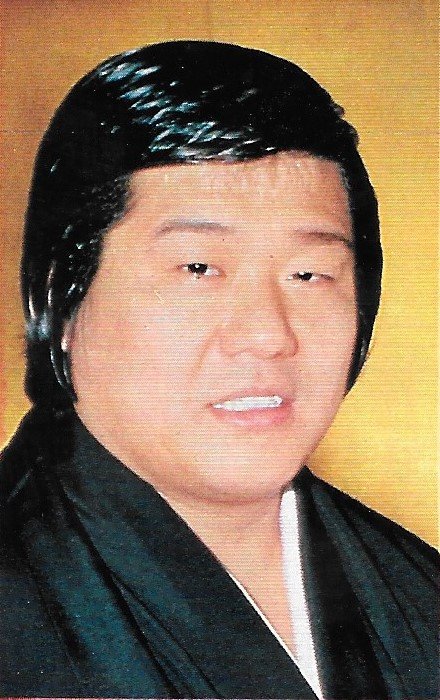

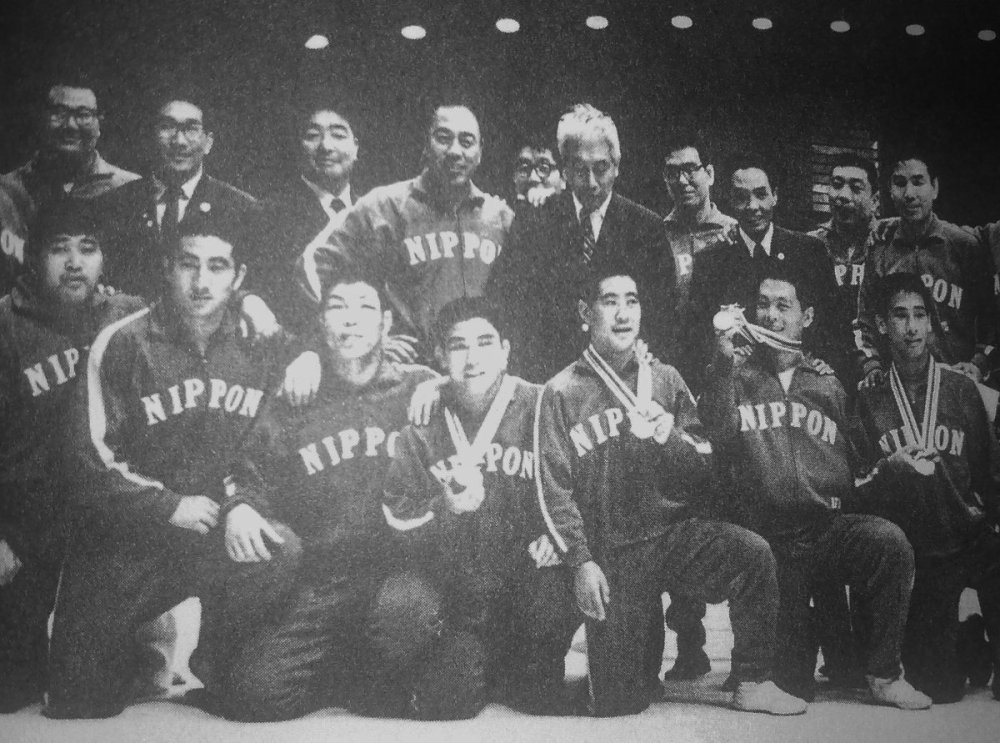

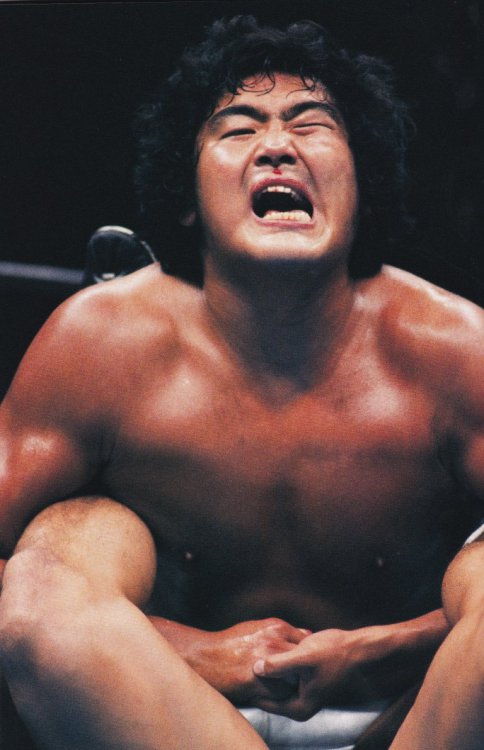

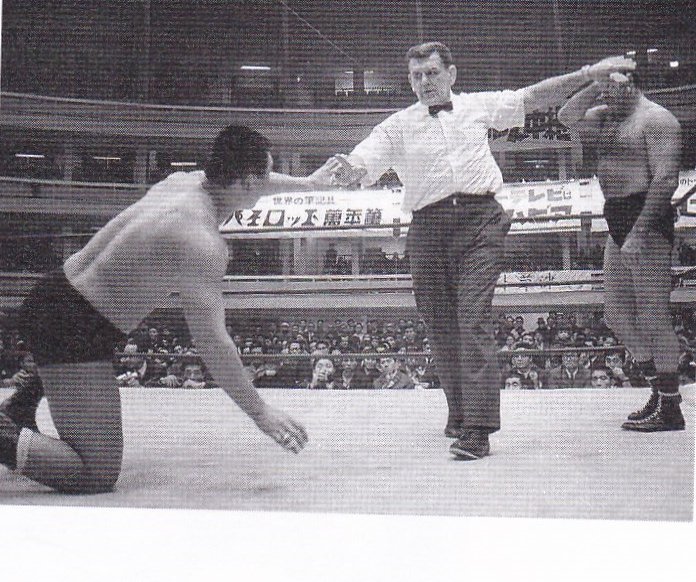

Rusher Kimura (ラッシャー木村) [KinchStalker Deluxe Profile #1] Real name: Masao Kimura (木村政雄) Professional names: Masao Kimura, Masami Kimura, Rusher Kimura, Great Kimura, Mr. Sun, Mr. Toyo, Professor Kimura Life: 6/30/1941-5/24/2010 Born: Nakagawa, Hokkaido, Japan Career: 1965-2003 Height/Weight: 185cm/125kg (6’1”/275 lbs.) Signature moves: bulldogging headlock, lariat, headbutt, butterfly suplex Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, International Wrestling Enterprise, New Japan Pro Wrestling, UWF, All Japan Pro Wrestling, Pro Wrestling NOAH Titles: “European Tag Team” [IWE] (2x, w/Great Kusatsu), TWWA World Tag Team [IWE] (1x, w/Thunder Sugiyama), IWA World Tag Team [IWE] (2x; 1 w/Thunder Sugiyama, 1 w/Great Kusatsu), IWA World Heavyweight [IWE] (5x), NWA Americas Tag Team [NWA Hollywood] (1x, w/Ryuma Go) Tournament victories: IWA World Series [IWE] (1973, 1977), Japan League [IWE] (1978) As the demon of the cage, Rusher Kimura became the heart of the IWE and eventually its ace. As the demon of the microphone, he became one of puroresu’s most famous promo-cutters and comedic performers. PART ONE: RUSHER RISING (1941-1973) “During his junior high school days, Kimura was a great hitter, batting fourth in the lineup. Even as a wrestler, he continued to go to Korakuen Garden, and he was a regular spectator at local baseball games (on the banks of the Arakawa River in 1962).” The youngest of four children, Masao Kimura played baseball at Saku Junior High when Rikidozan started puroresu’s first boom, and he admired the star wrestler. He would go on to Hokkaido Tenshio High School but dropped out to enter sumo. As he told the story, his older brother loved the sport, and the two went to an open practice session by the Miyagino stable, newly revived under retired yokozuna turned coach Yoshibayama. Yoshibayama told Masao that he had a good body, and after he was treated to some chanko, he “couldn’t refuse”. Kimura debuted for Miyagino in the March 1958 tournament. Under various shikona (he had settled on Kinomura by late 1962), Kimura competed for six years and reached the top twenty in the makushita division. Over Yoshibayama’s protests, Kimura retired after the September 1964 tournament. His goal had been to condition himself for pro wrestling, and as he saw it, if he made it to juryo he would never get out of sumo. Kimura sits with fellow Hokkaido native Shinya Koshika and stirs a pot of chanko during his time with the JWA. Kimura joined the JWA that October. Assigned as Toyonobori's valet, he debuted at a Riki Sports Palace show the following April with a match against Motoyuki Kitazawa. In his early career he performed under the ring name Masami Kimura (木村政美), almost certainly a Toyonobori invention. He wrestled for the JWA for ten months until he was swept up in his senior’s plans to form Tokyo Pro Wrestling. Kimura was gathered alongside Kitazawa, Tadaharu Tanaka, and Masanori Saito in February to begin training camp, and his expulsion from the JWA was announced the following month. Kimura spars with Antonio Inoki during their Tokyo Pro tenures. Issue #38 (2016) of the Showa Puroresu fanzine claims that Kimura’s “huge physique and natural ability” made him a wrestler to watch during Tokyo Pro’s brief life. As was revealed decades later, he had also scouted sumo talent for the company. However, despite swiping Antonio Inoki in the "Plunder on the Pacific Ocean" and starting strong with a well-attended show at the Kuramae Kokugikan, the organization shambled through its first tour. This was due to JWA aggression, failure to secure television network support, and of course, the rampant embezzlement of the man who had started the company. It all came to a head in the Itabashi Incident, when an outdoor show was canceled, and the spectators set the ring aflame in protest. After the tour ended in December, Kimura joined Inoki when he created a new Tokyo Pro separate from Toyonobori and Tanaka, and he was among the Tokyo Pro wrestlers who participated in the International Wrestling Enterprise’s first tour in January 1967. As Tokyo Pro completely fell apart, Inoki took his two valets Kitazawa and Haruka Eigen back with him to the JWA. Kimura began living in an apartment with Saito and Tokyo Pro recruit Katsuhisa Shibata and the three awaited a call from the JWA, while declining an offer from the IWE. While Shibata would get to join in early 1968, Kimura and Saito eventually accepted that they had burned their bridge with the company, and the two planned to begin wrestling as a tag team in San Francisco. When Kokusai came with another offer, Saito declined again, but Kimura accepted it. (As a result, Mr. Moto would book Saito to wrestle as Kinji Shibuya’s tag partner.) Kimura debuted in January 1968, during the IWE’s brief takeover by network Tokyo Broadcasting System and rebranding as TBS Pro Wrestling. Kimura’s most famous match from this year came in April, when he was Billy Robinson’s opponent for his Japanese debut, and he took Robinson’s butterfly suplex to lose the match. He suffered an early setback the following month when Billy Joyce injured his shoulder in a singles match. Kimura had originally been selected as the IWE’s first wrestler to go on excursion to England, but his injury led Shozo Kobayashi to be sent in his stead that autumn. He also missed out on the Hong Kong “market research” tour that summer, though he returned as an undercard referee in August. Kimura would get back in the groove for the last two tours of the year, and at the start of 1969, he received the ring name Rusher; this was the result of a fan contest, which had seen other candidates such as Strong, Yamato, Typhoon, and King. Kimura and Kusatsu celebrate with the European Tag Team titles on February 8, 1969. In the Big Winter Series’ tour program, TBS producer Tadadai Mori stated that Kimura and the now-renamed Strong Kobayashi would join Great Kusatsu, Thunder Sugiyama, and Toyonobori that year in the “establishment of five aces”. Sure enough, that year saw Kimura built up with tag title reigns alongside two of the three aces the company had established in 1968. With Kusatsu, Kimura won the European Tag Team titles from Andre Bollet & Robert Gastel in February. Then, in April, he and Sugiyama defeated Stan Stasiak & Tank Morgan to win the TWWA World Tag Team titles that Sugiyama and Toyonobori had just vacated. This was significant for being puroresu’s first hair match, and it led Kimura to receive his first IWA World Heavyweight title shot against Billy Robinson on May 5. (This match is currently missing from Cagematch records, but it happened.) As the TWWA tag titles were vacated in August to make room for the IWA World Tag Team titles, Kimura may have been originally intended to win them alongside Kobayashi in France. It would be logical that he would get the opportunity, and Yoshiwara and Mori had even suggested in the Osaka sports tabloid Weekly Fight Magazine that Kimura would be sent to Europe. Alas, Toyonobori was sent in his stead, and it would be two years before Kimura felt that belt around his waist. He had to make do with his first excursion. Kimura first worked in the NWA Central States territory under his own name, growing a mustache and donning a mawashi to work as a Japanese heel while being coached by Pat O’Connor. In his St. Louis appearances, he was Kinji Kimura; in Georgia Championship Wrestling, he was Professor Kimura; and in the AWA and its Nebraska-based affiliate All Star Wrestling, he was The Great Kimura. During his excursion, he would team up with future rival Killer Tor Kamata, and also donned a mask to team with Chati Yokouchi as the Masked Invaders. Kimura was successful enough in Central States to receive three NWA World Heavyweight title matches against Dory Funk Jr., and as Dave Meltzer would write, “many stated [that] he owed a lot to Bob Geigel” for the press coverage which these matches got in Japan. Kimura’s return match was a victory against a faux Blue Demon played by Les Wolff. He won the match using a distinctive submission technique, the “rotating foot” figure-four leglock. According to the Showa Puroresu zine, he only used it three times and it was supposedly not well-received. However, an uncited passage on the Japanese Wikipedia page for the figure-four leglock, which calls Kimura’s variation the “back foot” figure-four, states that this technique has since been used by the likes of Kendo Kashin and Yutaka Yoshie. It suggests a type of wrestler far from that which Rusher was about to become. It was on this first tour back home that he found his niche in the company. By this point, Kokusai’s television ratings stagnated around the 15% mark, and this tour had been damaged by JWA sabotage. Back in May, the company had held the You Are The Promoter poll to scout interest in wrestlers which had not yet worked in Japan. At the top of the list was Spiros Arion, and the IWE had booked him to challenge IWA World Heavyweight champion Sugiyama, but Arion had been incentivized to cancel this booking and claimed a shellfish allergy. (Blue Demon had placed fourth in the poll, hence Les Wolff's booking.) With Toyonobori retired and Kobayashi away on his second excursion, Kimura needed to establish himself as a top draw to help his company. In what one source states was his own request, Kokusai pulled a stunt that would come to define their legacy. On this tour, Rusher entered a bloody feud with Dr. Death; under the red hood, this was Moose Morowski, who became one of 70s AJPW’s most reliable midcard foreigners. On August 25, after Sugiyama’s successful IWA world title defense against Rene (billed as Jack de) Lasartesse, Dr. Death assaulted Sugiyama and Isao Yoshiwara until Kimura stormed the ring in plainclothes to defend them. On October 8, 1970, the two were booked to hash it out in puroresu’s first kanāmi (wire mesh) deathmatch: that is, a cage match. The IWE’s first attempt was amateur hour, as they had forgotten to add a door and the wrestlers were forced to hold the walls in place themselves. Nevertheless, Rusher defeated Dr. Death by knockout in seventeen minutes, and the match was broadcast in color six days later. The match was controversial among the press, as Professional Wrestling & Boxing magazine refused to publish photographs, and the sports papers dismissed it as “a dogfight”. The public response, a flood of complaints, was more damaging. It would be the only cage match to see television broadcast during the company’s TBS years, and their ratings also began to drop below fifteen percent. This would not discourage them from continuing to use the gimmick. Over the next eleven years, Kimura’s success in the stipulation earned himself the nickname kanāmi no oni (“wire mesh demon”). Alongside Kusatsu, Kimura also won a match for the vacant European tag titles. For the 1970 Big Winter Series, a second wire mesh deathmatch was booked for the last show of the year, using the TBS ban as a promotional tactic. It worked, and in the only time in its history, the IWE sold out Tokyo’s 5,000-seat Taito Ward Gymnasium on December 12. Rusher’s second opponent in the stipulation was the returning Ox Baker, who now sported his signature facial hair. Unfortunately, their December 9 match would have a significant effect on Kimura’s career. When future Blackjack Bob Windham tossed a chair into the cage, Baker took all the liberties, as contemporary coverage claimed that he had struck Kimura’s right leg some twenty times. Kimura won the match with a sleeper hold but was unable to walk. He would be hospitalized immediately and diagnosed with three complex fractures along his right tibia. The prognosis stated that Rusher would need six weeks of treatment and would have to wait ten weeks before he could exercise again. Alas, circumstances outside his control would compromise that, and as soon as after Christmas, Kimura would sneak out of the hospital for drinks with Animal Hamaguchi. The IWE managed the first tour of the year without him, but the smaller AWA Big Fight Series suffered sabotage when the JWA bumped their Kuramae Kokugikan show up one day to go head-to-head with Kokusai’s Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium event. This would be the first box office war in puroresu since the first Battle of the Sumida River in 1968. (What’s more, the JWA show saw Baba & Inoki defend their tag titles against Spiros Arion & Mil Mascaras: the top two of the IWE’s own You Are the Promoter fan poll.) Yoshiwara needed as much native talent as possible, and even flew to West Germany to bring Mighty Inoue back from his excursion. Even he did not dare ask Kimura to try to speed up his recovery, but Rusher felt deeply obligated to Yoshiwara for having given his career a second wind after Tokyo Pro’s demise. As the story goes, he resolved to work the Tokyo show even if it killed him, and Yoshiwara wasn’t in a position to not acquiesce. Kimura was booked to wrestle the ‘?’, a masked Angelo Poffo, in the wire mesh. The circumstances robbed the match of the buildup heat the other two had had, and photographs of Rusher wrestling in a knee-high cast tell it all. He won, of course, but he could not use much of his signature repertoire and was again unable to walk afterwards. His fellow wrestlers had to open the cage to carry him out on a tatami mat. As the show drew a paltry three thousand, it hadn’t been worth it. Kimura resolved to work the 3rd IWA World Series tour afterwards, but two of his bones became dislocated. After this, he developed a posture which leaned to his left side to reduce strain on his right knee, an imbalance that would bring years of back pain and help develop spinal stenosis. Outside of his wire mesh proclivities, Kimura fought for the IWA World Tag Team titles in the second half of 1971. With Great Kusatsu abroad on his second excursion, Rusher teamed up with previous co-champion Sugiyama. The two lost a match for the vacant belts against Red Bastien & Bill Howard on September 7, 1971, but they won them in a rematch at the end of the tour to begin an eight-month reign. In 1972, Kokusai’s dependence on the wire mesh deathmatch for ticket sales became clear. Rusher went over Kenny Jay in the cage on the first show of the year, which led even Monthly Gong, which had been the one part of the wrestling media to cover the stipulation evenhandedly, to remark in a photo caption that they wished that the IWE would exercise restraint in the future. They wouldn’t. That May, Kimura & Sugiyama vacated their titles after a final successful defense against Ivan Buyten and Monster Roussimoff (that is, Franz von Buyten and Andre the Giant), as Sugiyama transitioned into a part-timer to focus on his business pursuits, which would lead him to transfer to All Japan Pro Wrestling. On September 9, Rusher defeated Buddy Austin in the cage for his sendoff show before a second excursion. Left: Kimura sits with Kiyomigawa in France. Right: Kimura with Hiroshi, the stepson whom he met during this excursion. Kimura returned to Japan in time for the 1973 Dynamite Series. It was at this time that he added a butterfly suplex, which broadcasters would dub the Rusher suplex, to his repertoire. This tour saw him defeat Ric Flair in the latter’s Japanese debut. Backstage, Isamu Sakae became his valet. Kimura became very close to the future Snake Amami, who Hiroshi later called the best person he ever met in the business. Rusher returned to a company which had become so dependent on the gimmick he had brought to them that it had directly damaged them. The unavailability of some venues had forced Kokusai to book wire mesh deathmatches on taping dates, which had led TBS to permanently slash the program to thirty minutes. With Sugiyama permanently transferred to AJPW, Kimura teamed up with Kusatsu on his return tour to challenge Mad Dog Vachon & Ivan Koloff for the IWA tag titles. Their first attempt on April 30 was unsuccessful, but they prevailed in a May 14 rematch. The duo would hold the belts for nearly two years. Meanwhile, Kimura made history that summer. On June 21, the IWE announced that he would receive an IWA World Heavyweight title shot on July 9. After Kobayashi retained against Dick Murdoch on June 29, this meant that Kokusai would hold puroresu’s first top title match between native wrestlers in eighteen years. Supposedly, this was Kokusai’s response to Antonio Inoki’s calls for a unified Japanese commission to decide the nation’s true champion. The Rusher Suplex won the first fall, but Kobayashi would prevail to continue what would be a 25-defense reign. Unfortunately, the Osaka show drew an announced 4,500, a dismal number compared to that which New Japan had drawn the previous month with the first Inoki vs. Tiger Jeet Singh match. In autumn, Kimura entered the 5th IWA World Series tournament. (The previous year, the IWE had announced that future iterations of the tournament would be held in the fall instead of spring so as not to have to compete with the JWA’s World League.) He was put in the A block, with fellow natives Kobayashi, Isamu Teranishi, and Tadaharu Tanaka, and gaikokujin Lars Anderson, Moose Cholak, Bob Bruggers, and Flicky Alberts. The ace Kobayashi was the favorite to win the block and the tournament, but after Kobayashi defended his world title against Verne Gagne twice, his massive upset loss to Teranishi made Kimura the native with enough points to advance to the four-man semifinal round. At what in kayfabe was his opponent’s request, the cage was set up for Kimura and Anderson’s block match on September 27. Lars disassembled the ropes and busted Rusher open with the metal fittings, but Kimura choked Anderson with the ropes before hitting his signature suplex for the knockout victory. Kimura and Bruggers advanced to the semifinals, where Rusher prevailed in the cage. On October 10, Kimura defeated Blackjack Mulligan in a bloody brawl to win the tournament. In late 1973, Kimura’s 29-win streak in the wire mesh deathmatch was broken when he and Ole Anderson, avenging his kayfabe brother, went to a double knockout finish. Rusher got his heat back against Ole with a win in the cage one week later. Kimura stretches out Blackjack Mulligan in the 1973 IWA World Series final.

- 3 replies

-

- jwa

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

- (and 6 more)

-

3000 words written for the Rusher Kimura profile, and I'm not even in 1974 yet. I want this biography to serve as a preview of the scope I plan to write at if and when I write bios for the biggest names in puroresu history.

-

My subsequent research suggests that "Jumbo" had been in mind for his ring name long before the poll. Coverage of Tsuruta from as far back as the January 1973 issue of Monthly Pro Wrestling uses "Jumbo", and there was a ten-part serial in the same magazine, starting that March, called "Fly, Jumbo!". (I am slowly translating this serial as a resource for a book that I plan to write.) I now suspect that Jumbo had been the brainchild of AJPW commentator and Tokyo Sports reporter Takashi Yamada - the nicknames used for foreign wrestlers in puroresu were Tokyo Sports inventions for marketing - and that the fan poll was intended more to give a veneer of fan engagement and/or see if the public chose a different name. I also have an insert poster from the August 1977 issue of Monthly Pro which uses the verbiage Tomomi "Jumbo" Tsuruta, which I think suggests its origins as a Yamada nickname. Tsuruta is called "Jumbo" in the January 1973 issue of Monthly Pro.

-

UPDATES, JULY 2022 I spent this month writing profiles for the International Wrestling Enterprise. I made progress on a Rusher Kimura profile that I intend to be the most detailed that I have yet written (as a warmup for the heavy hitters), but it might not be done until fall, as I am waiting to receive and transcribe a resource that I want to cite in it. New Profiles Animal Hamaguchi (Wrestler/Trainer, IWE/NJPW/Japan Pro) Goro Tsurumi (Wrestler/Promoter, IWE/AJPW/SWS/NOW/Kokusai Pro Wrestling Promotion) Great Kusatsu (Wrestler/Executive/Booker (show), JWA/IWE) Isamu Teranishi (Wrestler, Tokyo Pro/IWE/NJPW/Japan Pro/AJPW) Katsuzo Oiyama (Wrestler, IWE) Mighty Inoue (Wrestler/Referee/Broadcaster, IWE/AJPW/NOAH) Ryuma Go (Wrestler/Promoter/Trainer, IWE/NJPW/UWF/AJPW/Pioneer Senshi/Oriental Pro/Samurai Pro Wrestling) Strong Kobayashi (Wrestler, IWE/NJPW) Tetsunosuke Daigo (Wrestler/Booker (talent)/Trainer, Tokyo Pro/IWE) Thunder Sugiyama (Wrestler, JWA/IWE/AJPW)

-

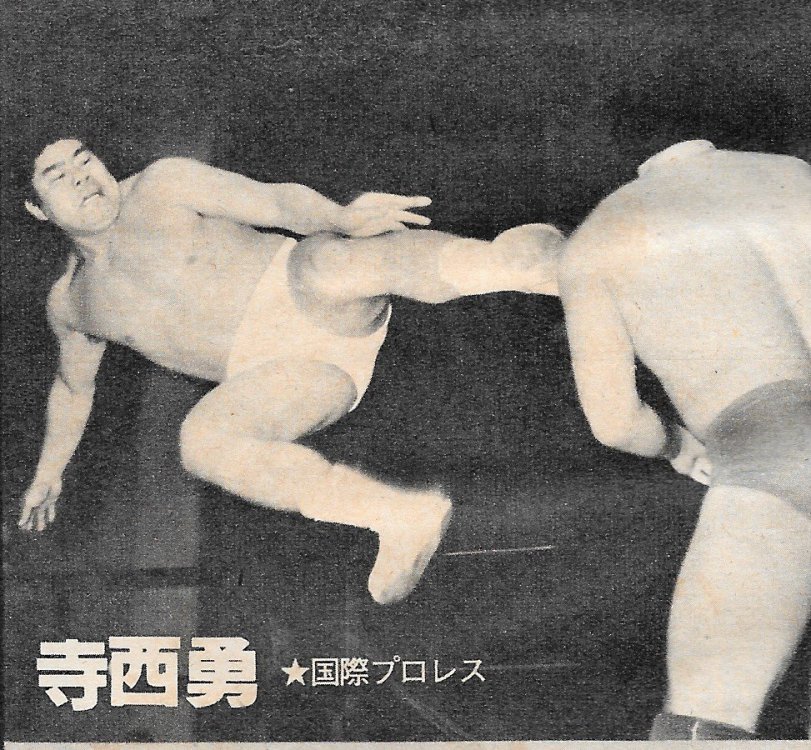

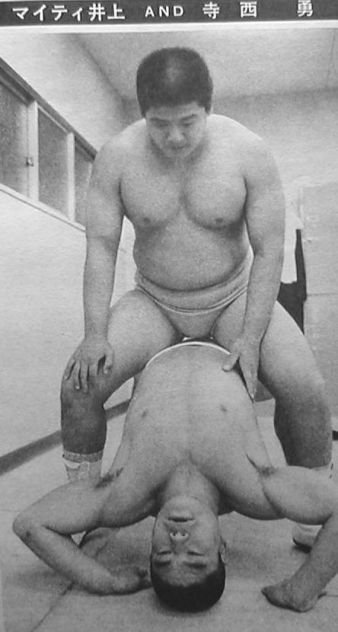

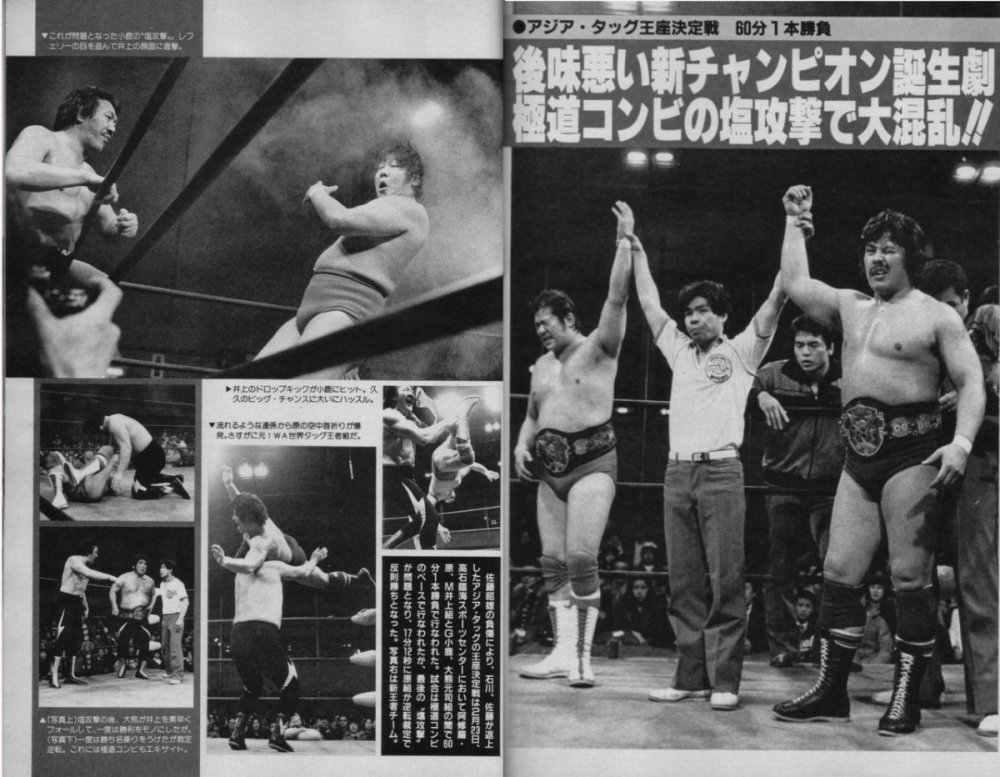

Isamu Teranishi (寺西勇) Real name: Hitoshi Teranishi (寺西等) Professional names: Isamu Teranishi Life: 1/30/1946- Born: Irumizu, Toyama, Japan Career: 1966-1997 Height/Weight: 175cm/100kg (5'9"/220 lbs.) Signature moves: bridging German suplex Promotions: Tokyo Pro Wrestling (Toyonobori), International Wrestling Enterprise, New Japan Pro-Wrestling, Japan Pro Wrestling, All Japan Pro Wrestling Titles: IWA World Mid-Heavyweight [IWE] (2x), All Asia Tag Team [AJPW] (2x, 1x w/Animal Hamaguchi, 1x w/Norio Honaga) The IWE's “Japanese mat magician”, the agile, technical Isamu Teranishi was one of pre-Fujinami puroresu's most influential junior heavyweights. Hitoshi Teranishi entered the Tatsunami sumo stable and debuted in May 1963. He spent three years with them before retiring in 1966. He was one of six ex-sumo wrestlers to join Toyonobori’s Tokyo Pro Wrestling in time for its first training camp, alongside: fellow Tatsunami alumni Takeji Suruzaki and Haruka Eigen; former Nishonoseki wrestler Tsuyoshi Sendai; and former Asahiyama wrestlers Katsuhisa Shibata and Hiroshi Nakagawa. Even considering the profession, Teranishi’s early path was assuredly filled with hardship. His trainer, Tadaharu Tanaka, had misappropriated the funds allocated for their training camp. These men were broken in on a beach, as there was no money to build a ring, and according to Eigen, they made less money than civil servants and were not even fed rice. While Nakagawa would leave the company after its shambling tour of late 1966, the other five joined Antonio Inoki that December when he created a parallel Tokyo Pro Wrestling company and transferred the whole roster except Toyonobori and Tanaka to it. Teranishi worked on the Tokyo Pro-IWE joint tour of January 1967 and would join the latter after Tokyo Pro’s collapse. Teranishi defied his sumo background through an agile, dropkick-throwing style. He was the first Japanese wrestler to perform a spot which has now become commonplace among junior heavyweights, in which one lands on their feet after a back body drop to turn around and counterattack; Teranishi borrowed it from Tony Charles. While he would receive some training from Billy Robinson, he was never chosen for an overseas excursion, and never worked outside Japan save for in Southeast Asia. Teranishi’s early years are noted for his rivalry with Mighty Inoue, who was highly influenced by him. His earliest surviving match, though, is a six-man tag alongside Rusher Kimura & Thunder Sugiyama in 1972, against a foreign team led by Andre the Giant. Teranishi in the late 1970s. In October 1973, during the 5th IWA World Series tournament, Teranishi scored a massive upset against company ace Strong Kobayashi and kept him from advancing to the finals, which would be won by Kimura. This was one of multiple factors that led Kobayashi to quit the company in early 1974. In 1975, the IWA World Mid-Heavyweight title was revived after four years, and Teranishi defeated Jiro Inazuma (Gerry Morrow) to become puroresu’s last junior heavyweight champion before the start of the junior boom in the late seventies. He would vacate the title a month later, but it was revived again in 1976 and he beat Inazuma for it again. While the Showa Puroresu fanzine states that all of his defenses were taped and broadcast at the time, no footage was found when the Tokyo 12 Channel archives were searched for IWE’s DVD box sets in the 2000s. Teranishi won a Tokyo Sports award for the skill he displayed during his second reign, but after a December 1977 defense against Devil Murasaki, the title was quietly phased out, and replaced with the WWU World Junior Heavyweight title for Ashura Hara’s run as IWE junior ace. After Kokusai’s collapse in 1981, Teranishi joined Kimura and Animal Hamaguchi as one-third of the Kokusai Gundan heel stable. This would make Teranishi one of the most hated heels in the country for a time, but like Hamaguchi he left Kimura to join Riki Choshu’s Ishingun in 1983. This period gave him opportunities to show his skill as a junior-style wrestler, competing as an Ishingun junior alongside Kuniaki Kobayashi. Teranishi would even be the final opponent of Tiger Mask’s original run, challenging for his NWA International Junior Heavyweight title on August 4, 1983. In late 1984, he left the company in a splinter faction led by Choshu which would become Japan Pro Wrestling, and as a JPW member participated in the two-year feud against All Japan Pro-Wrestling. In the first phase of the JPW-AJPW period, Teranishi eked out a spot for himself in the All Asia Tag Team title scene, first winning the belts alongside Hamaguchi in July and winning them again that October when Hamaguchi became sick, wrestling with Norio Honaga. After JPW’s collapse, Teranishi was among those who decided to fold into All Japan. He would remain with them until a 1992 cervical injury led him to retire. After this, he remained involved for a period as full-time staff, overseeing pamphlet sales at shows, but Teranishi made a handful of returns from 1994 through 1997. These were with Takashi Ishikawa’s Tokyo Pro Wrestling (making Teranishi the only wrestler to wrestle for “both” Tokyo Pros), Great Kojika’s Big Japan Pro Wrestling, and finally, New Japan, for whom he worked in 1995 on shows under the Heisei Ishingun branding. His last match would be at an independent show marking Masahiko Takasugi’s 20th anniversary. Outside of an appearance at New Japan’s 2002 30th Anniversary show, Teranishi has stayed out of the business since then. Miscellaneous Teranishi would be nicknamed the Japanese Édouard Carpentier in his IWE years, although Teranishi admits that Carpentier did not make a particularly strong impression on him when he appeared for the company in the early seventies. His white trunks were suggested by Tadaharu Tanaka to make him look taller.

-

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

- iwe

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-