-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

Masami Soranaka (空中正三) Profession: Referee, Wrestler, Trainer, Booker Real Name: Masami Soranaka Professional names: Mr. Soranaka, Masami Soranaka, Shozo Soranaka Life: 5/15/1944-6/11/1992 Born: Kobe, Hyogo, Japan Career: 1978(?)-1992 Promotions: Universal Wrestling Federation (1984-5) Summary: Karl Gotch's son-in-law Masami Soranaka was an easy-to-overlook but important early builder in shoot-style. Masami Soranaka was born in Kobe in 1944. His brother was Hawaii-based wrestler Hiro Sasaki, who briefly held tag gold with Kendo Kimura in Puerto Rico and Tor Kamata in New Zealand, and also booked Hawaiian wrestlers for New Japan. More interesting than anything in Sasaki’s in-ring career, though, was his double job as a DEA agent; in the mid-1980s he enacted an ultimately unsuccessful entrapment scheme against the Yamaguchi-gumi, which involved an arms deal with a fictional Hawaiian mob and the rights to a Michael Jackson tour. (Sasaki’s wife, television personality Cathy, is also notorious for having been a lover of singer Naomi Sagara, and torpedoing both their careers when she outed her in a 1980 talk show interview.) Soranaka, who had experience in judo, karate, and sumo, became the son-in-law of Karl Gotch when he married his only daughter, Jennie. He may have interpreted for Gotch during his coaching stints for New Japan Pro Wrestling, and Soranaka debuted as a referee in spring 1978, during the 1st MSG Series tour. Among other matches, he refereed Antonio Inoki’s NWF title defense against El Canek in the UWA. I presume that these duties continued when Gotch was with NJPW. According to Fumi Saito, who got back to me after I originally posted this, Soranaka also wrestled alongside his brother in Puerto Rico prior to his UWF "debut". In 1984, Soranaka followed Gotch when he began associating with the UWF and continued to work as a referee. However, a talent shortage led the 40-year-old to become the UWF dojo’s first graduate and wrestle for the promotion. He was billed as Shozo, in reference to the more common but incorrect reading of his first name (正三). According to Dave Meltzer’s obituary, he would follow this up with some work as an Oriental heel for small Florida shows. In his later years, “Sammy” Soranaka worked to establish shoot grappling in the United States. He never worked for the UWF’s second incarnation, but he helped them in his own way when he offered his coaching services to the Malenko wrestling school. Soranaka helped develop foreign talent who could work as competent midcard talent in the shoot idiom, such as Norman Smiley and Bart Vale. Yuji Shimada also came from Japan to learn catch wrestling from him and was also taught refereeing. The most important person he trained, though, was Ken Shamrock. He and Vale formed the International Shootfighting Association, of which he was president until his death. After the UWF’s implosion, Soranaka continued to offer his booking services to Pro Wrestling Fujiwara Gumi. Soranaka died of a brain tumor in 1992. In Fumi Saito’s documentary Karl Gotch: Kamisama, which was shot in the summer of 1992, Fujiwara is seen visiting Soranaka’s grave.

-

READ THIS IF YOU ARE NEW TO THE THREAD. Now that this is a proper thread, I should note that this first post covers the third interview in this series, as it was the first I acquired. The below posts cover the first and second while being substantially fleshed out with a general history of the company. (This is particularly after the first numbered post, which focuses on the business side of NJPW's first year. I eventually wish to expand this first post into multiple entries covering the year properly, with new resources that I may soon take a research break to transcribe.). As of February 2023, I have finished 1974, and have about two more years of material to cover in future posts before I reach the point that this first post covered. Once I have reached it, I will expand this properly. While the 2020-2022 Naoki Otsuka interview serial was the inspiration for this thread, I believe that the Western understanding of early New Japan history is far, far too poor for me to just recap it without context. Honestly, it's not really about him anymore, and if I can get this its own folder in the forum like my Four Pillars bio recaps, I will probably request that it be renamed. Quarterly puroresu magazine G Spirits (a spiritual successor to Gong, involving ex-Gong editors Kagehiro Osano and Tsutomu Shimizu) serialized an interview with Naoki Otsuka. I only have the third part of it in issue 58, which mostly covers the span from after the Ali-Inoki match through early 1978 (stopping right as Fujinami returns). I transcribed this because it was on hand and I wanted material on the company's financial situation for a planned blog series on the 1983 coup and what led to it. If I really want to do that series right, I’ll need to put it on hold until I can transcribe later parts of the interview. I have already transcribed a 1984 Weekly Pro article by Otsuka which convinces me that he will be able to discuss Anton Hi-Cel and sister business Anton Trading in more detail.1 It was still going as of the latest issue, for a total of at least eight parts. I have placed an order for the issues with parts 4-7, as they were in stock at Toudoukan, although I do not know whether I will give those this same treatment or save them for the coup series. But even just these ten pages contain the most detailed insight I’ve ever read on what it was like to run a puroresu promotion at the ground level. First, I should give some background. Naoki Otsuka was originally NJPW’s ring announcer, but he transferred into sales as Inoki’s brother-in-law, Tetsuo Baisho, took that job. The interview indicates that Otsuka had been the deputy manager of the sales department, and that he had been charge of sales in Osaka, Okinawa, and Sapporo, but this part of the interview begins as he was transferred to the general manager (or simply “sales manager”). In 1983, Otsuka was the one who discovered that Inoki had misappropriated company funds to cover his losses in Anton Hi-Cel. He would later become famous as the president of Japan Pro Wrestling. (See the JPW posts elsewhere on this subforum for a rundown on what happened there, although keep in mind that I intend to expand that substantially with the coup series…whenever I can make that happen.) --- POST-ALI RESTRUCTURING The Ali-Inoki match worsened a deficit NJPW already had. On top of Ali’s steep fee, it had been expected that NJPW would receive $1 million in revenue from closed-circuit broadcasts, but the real payoff was much lower. Inoki was demoted from president to chairman for a time, while Hisashi Shinma was demoted from general manager of the sales department to a regular employee. New Japan would demand compensation from Ali, claiming that the revenue had been damaged by the rule change his camp had enforced, and Ali would sue for breach of contract. Inoki promoted Otsuka to sales manager, choosing him over fellow employee Takeji Fukunaga because of his stronger backbone. Shinma was still considered an informal boss by the sales department, who continued to refer to him by his old title. Network executives, referred to by a begrudging Inoki as “occupying forces”, took positions in NJPW. The interview identifies one of them as Kohei Nagasato, who had been the head of NET TV’s sports department. This interview does not specify when the network executives were no longer assigned to the company, implying that it lasted past the range of time this part covers. Just know that Nagasato would return to an executive position in NJPW after the network takeover of 1983. It was around this time that Inoki discreetly registered a company. New Japan Pro-Wrestling Kogyo Co. was registered in Tokyo’s Nerima Ward with a capital of three million yen. The locale was because he could not register the company in Shibuya, and his in-laws lived in Nerima. Inoki had the idea that, if he could register this company in a different ward, he could transfer all the wrestlers to this side company in the event of a full network takeover or other major dispute. Interestingly, this was not the same New Japan Pro-Wrestling Entertainment company that Otsuka was put in charge of in 1983. That company’s capital was insufficient, so a new company of the same name was formed. Otsuka states that he did not know about the original Entertainment company until “well after the fact”. SALES SHOW WOES When Otsuka was promoted, he discovered the extent to which “uncollected money” had been weighing their ledgers down. Inoki told him that he would be able to collect “about 30 million yen a year”, but then Otsuka got into the books and found that New Japan had been losing 100 million per year. The puroresu touring model was mostly based on two kinds of shows: the company-run “independent shows”, and locally purchased “sales shows”. One always wanted to get as many sales shows as possible, because independent shows required you to cover the operating costs, as well as send company people to facilitate them. Sales shows were the majority of the problem. The contract for a sales show stated that half of the fee was to be paid at the time the contract was signed, but this advance pay had rarely been honored unless it was a first-time client. Some promoters did not even pay this fee on the day of the show, or they would do so with dishonored bills. Furthermore, Otsuka states that some promoters pocketed the second half when they made a loss. One of Otsuka’s measures to combat this was to make a small change on the contract. Originally it had read “Representative Director Kanji Inoki”, and it would have named Otsuka as a representative director as well, but Otsuka changed the title to his position of NJPW sales manager. This allowed him to be strict in collecting money, as he was now the direct contractor. If, for example, Inoki had to miss a show, this meant that Otsuka could stand firm and insist to the terms of the contract, instead of being given the runaround to ask Inoki for a discount. Otsuka never cancelled a show, but he had to threaten to do so. He even recalls one incident where a sales employee had to be assigned to the ticket booth to make sure New Japan got their cut. Over time, though, these issues decreased. Otsuka also encouraged promoters to have good relations with the company by beginning a “national promoters conference”. He would select “around ten” promoters from across the country to take an all-expenses-paid trip to Tokyo and attend Nooj’s year-end Kuramae Kokugikan show, and then receive a commemorative gift from Inoki at a Keio Plaza Hotel conference the following day. There were some problems with independent shows as well. These came down to ticket sellers who would receive two-to-three hundred tickets, sell them, and never give New Japan their cut. Otsuka says it was very difficult to get that money back. DAFUYA This actually comes later in the interview, but I think it fits better around here. Shimizu brings up the topic of scalpers, and Otsuka takes the chance to clarify the “taboo” relationship between dafuya and promoters, while getting into the nitty-gritty of selling tickets. Otsuka claims that he didn’t get involved with dafuya when he was working sales in Osaka. However, the person who asked them for advance tickets had an understanding with scalpers. The scalpers would buy advance tickets, which normally cost ¥7000, at ¥3500, and then sell the tickets at fixed prices. As sales manager, Otsuka would become more directly involved with them when overseeing shows in the Kanto/Tokyo area. When ticket sales were sluggish, Otsuka would sell one to two hundred tickets for the most expensive seats (¥7000) to dafuya at half price. The scalpers were good enough at their trade to sell those tickets at full price, but the company didn’t concern itself about losing those sales. In those cases, there were many more customers who would buy cheap tickets directly from the ticket booth. Another way that the box office would do business with scalpers hinged around standing-room-only tickets, which were regularly priced at ¥1500. There were days when the standing room was sold out but there were still empty seats, and this was not a profitable arrangement for the box office. So, they would only print around 500 SRO tickets to start with and get those sold, so that that people would be forced to buy seats despite there still being standing room. The dafuya were smart enough to ask how sales were going on a given show, and waited like hyenas for when the SRO tickets were really about to run out. Then, the scalpers would buy 50 or 100 SRO tickets. Now that the standing room tickets were sold out, the ticket booth would not offer any discount, and a seat would cost ¥3000. Meanwhile, the scalpers could mark up all those SROs to ¥2000. If a dafuya couldn’t get tickets directly, they plied their trade using “invitation tickets”, which they bought for cheap from people who couldn’t come to shows. Then, they would actually go to the venue to check where the invitation tickets would go. These always depended on what seats were available, meaning it could range from a premium ringside seat to a row on the second floor. Naturally, they would price the tickets accordingly. Both Otsuka and Shimizu recall a particular scalper, Kuro-chan. He was a tekiya (itinerant merchant) who traveled around the country. He could be seen at New Japan and All Japan shows, and Shimizu remembers that Kuro would always shoot the shit with him before shows, likely to try to get information from the press. Kuro would later become a frequent fixture at AJW shows (Otsuka did some sales work for them later on), which sold discount tickets (I’m guessing these were age-based). Kuro would buy ringside tickets, and scalp them to the girls standing in the long ticket booth line. In recent years, nuisance prevention ordinances ended the traditional dafuya – who, to be clear, could be found scalping tickets to all sorts of entertainment and sporting events – and Otsuka has heard that they now deliver tickets through the mail. BOOKING TOURS It was the sales manager’s responsibility to arrange tours. Otsuka would not begin doing so until 1977 because the company had to plan their tours by the year, due to the requirements of major venues. Otsuka gives the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium as an example; it required New Japan to submit their requested dates by the end of February. Requests for big-market shows were generally on Thursdays, which I will explain later on. “In those days, Osaka was scheduled five times a year, Sapporo two or three times, Kagoshima twice, Takamatsu twice, and so on.” The basic pattern of a NJPW tour was already in place; it would last either four or six weeks, and it would travel the Japanese archipelago in a figure-eight centered on Tokyo. Tours would begin in Korakuen Hall, and end at the Kuramae Kokugikan or Nippon Budokan. For Kuramae, sumo was the greatest priority, but NJPW planning department head Akio Nakane was very friendly with the sumo association person in charge, so they were able to learn the sumo schedule. Otsuka would then submit the ideal choice and one backup, and depending on the decision, the entire tour would sometimes be shifted back one week. Once the big venues were secured, it was Otsuka’s job to apply for the small and medium venues that made up each tour’s connective tissue. As gaikokujin were paid flat weekly fees, one wanted to stretch those dollars as much as one could.2 The goal was to have at least six shows booked per week, and ideally seven. The record was 1975’s 210 shows, and they aimed to reach 200 per year, although the two “martial arts shows” per year made that hard to achieve. The department would determine where they wanted to book shows, and at what price. The department would call local promoters to ask them if they wanted to do business with them at x venue on y date, or if they wanted to do a show in a market which New Japan would be passing through: for example, “Can you do Fukuyama on the day between Okayama and Hiroshima?” In order to encourage promoters to accept a show contract, a column featured which foreign wrestlers were to participate on that tour. (Osaka-based taboid Weekly Fight Magazine, which started the katsuji puroresu style of coverage that Weekly Pro would bring into the mainstream in the 1980s, appealed to hardcore fans for its willingness to leak foreign bookings multiple tours in advance. This was one way that such information would have reached them.) Otsuka states that this was a decisive factor in whether promoters would accept a contract, and that NJPW’s dearth of top gaikokujin in 1977 really bit them here. “If it was [Tiger Jeet] Singh or Andre the Giant, you could be sure that [the promoter would buy the event],” but if you didn’t have those marquee names for that tour, things could get dicey. Sometimes, the best you could get was the third type of show, the “branch show”. These represented a middle ground between the independent and sales show. The company partnered with promoters, so no one from New Japan had to go to the site. However, NJPW would take on the venue booking fee, printing costs, and other expenses, and split the rest with the promoters. Otsuka claims that, later on, he was the one who asked Masa Saito to track down Stan Hansen as a potential new foreign “ace in the hole”. Saito eventually found him “in North Carolina or Georgia”, and Hansen returned in 1979 for the second MSG Series. Promoters eventually said “if not Singh or Andre, then Hansen is fine”. (Otsuka also cites Sean Regan as a specific gaikokujin who he had wished to see return, but he had become a schoolteacher by then. Regan eventually called him in 1979 and worked a single tour.) TELEVISION Otsuka was also required to be present at all television tapings. The presence of a television crew required some seats to be stripped from a venue for the cameras, and this sometimes caused problems with the promoter. The network could not deal with on-site disputes like that, so they needed Otsuka there to set things straight. Otsuka’s central role in putting tours together and dealing with television tapings even extended to some booking influence. When Seiji Sakaguchi became vice president, he was able to “talk with him more familiarly” concerning the matches that Inoki and Kotetsu Yamamoto were booking. Otsuka would give input to them while submitting show cards to the network, suggesting that this was how TV taping dates were decided on. I mentioned earlier that big-market shows were generally booked on Thursdays, and this was why. World Pro Wrestling was broadcast live at the start of each tour and on subsequent b-show tapings, but major events were taped. Inoki was concerned about the “flow” of World Pro Wrestling, so as Tatsumi Fujinami corroborated in a recent Weekly Pro interview, he supervised the production of these ‘major’ episodes, directing camera cuts. (This was years before Vince McMahon took a similarly hands-on approach.) Despite competing with the “monster program” Taiyo no Hoero!, a police procedural which had taken Nippon Television’s Friday 8:00PM timeslot since they had dropped the JWA (AJPW aired on Saturday), Otsuka states that World Pro Wrestling was consistently getting ratings above 10%, sometimes close to 20%. ---- For me, all that is the meat of the article. Here are noteworthy bits from the rest. On March 31 and April 1, 1977, NJPW became the first promotion in twenty years to book Kuramae on back-to-back nights. On the first day, Seiji Sakaguchi defeated the Masked Superstar in the 4th World League, while Inoki successfully defended the NWF Heavyweight title against Johnny Powers. On the second day, which coincided with NET TV’s name change to TV Asahi, Inoki and Sakaguchi reformed their Golden Tag Team to challenge Tiger Jeet Singh & Umanosuke Ueda for the NWA North American Tag Team titles, which Singh & Ueda had won from Sakaguchi & Kobayashi through dishonorable means two months before. Otsuka seems to regret his ambition. The interest in the World League tournament had waned due to Inoki’s decision to stop entering it the previous year, which hurt the first show’s business. Also, that show was on a Thursday, so those who went to see the second show missed the first day’s episode of World Pro Wrestling. Inoki gave him a slight scolding, but Otsuka thinks he paved the way for the G1 Climax’s multi-night stints at the Ryogoku Kokugikan. In May, Shinma and Nagasato traveled to the United States. Shinma’s lawyer had recommended they go to trial against Ali, since the yen had appreciated from 310 to 200 to the dollar, but they decided to settle. They also secured a contract with “Monster Man” Everett Eddy to bring the different styles fights back into full swing. This was when these special “fights” began to be broadcast on the Wednesday Special sports timeslot instead of as part of World Pro Wrestling. The return of the DSF would go a long way towards rehabilitating Inoki’s reputation after the Ali debacle, and the television situation functionally gave NJPW an extra episode’s worth of TV money whenever they booked a DSF. They would take advantage of that in the coming years, and at one point, they even considered expanding into a full “martial arts” wing. Inoki’s valet Satoru Sayama, who was his sparring partner and had even conceived of open-finger gloves for Inoki’s DSF against Chuck Wepner, would have been a major part of the division. The nail death match between Inoki and Ueda on February 8, 1978 could have been even wilder. While brainstorming a gimmick match that would prevent Ueda from escaping the ring, Otsuka pitched scattering the ring mats with broken beer bottles or surrounding the ring with a water tank, but the Budokan never would’ve approved. The nail idea then came up, and after Otsuka explained the idea to commentator Ichiro Furutachi, who would promote it during the Sapporo shows the previous week, the tickets sold at an unprecedented, “explosive” rate. Two days after that show, Otsuka also got NJPW a variety show-esque gig to broadcast on the aforementioned Wednesday Special timeslot. Among other things, Kengo Kimura sang a Pink Lady cover with Chieko Matsumoto, Yoshiaki Fujiwara cooked, and Inoki & Sakaguchi wrestled the Hollywood Blonds. This part ends with some words on the Dragon Boom, the popularity spike after Tatsumi Fujinami returned from his three-year expedition. Otsuka states that, prior to this, he had planted young women in the front row at Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium shows for about two years (“It was an image strategy to improve the TV ratings”), but Fujinami made any such deliberate effort unnecessary. Otsuka recalls that he used to hold autograph sessions at supermarkets by promoters’ request, and that these had been inconvenient to coordinate because they had happened on the day of the show, and the clients had always requested that Inoki be there. By about the third tour of Fujinami’s return, though, New Japan began receiving requests for Fujinami autograph sessions, and Fujinami was “easy to ask”. Fujinami even motivated younger fans to go out of their way to see him wrestle. Otsuka gives the example of people from Okayama who would come to shows in Himeji or Osaka, or even plan an overnight trip to Tokyo.

-

This post cannot be displayed because it is in a password protected forum. Enter Password

-

Takao Kuramochi (倉持隆夫) Profession: Commentator (PBP) Real name: Takao Kuramochi Professional name: not applicable Life: 1/2/1941- Born: Mitaki, Tokyo, Japan Career: 1972-1990 Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Takao Kuramochi called All Japan Pro Wrestling for almost twenty years and remains one of puroresu’s best remembered play-by-play men. A graduate of Waseda University’s law department, Takao Kuramochi joined Nippon Television as an announcer in 1964. When NTV began airing AJPW eight years later, he was recommended as an announcer by Kazuo Tokumitsu. Kuramochi gradually took over lead broadcast duties from Tokumitsu and Ichiro Shimizu. By 1978, which is the first year of AJPW television that mostly still circulates today, he had settled into the head position. Kuramochi and reporter-commentator Takashi Yamada were the core duo of All Japan broadcasts for many years. In a 2022 column, Tokyo Sports reporter-turned-commentator Soichi Shibata praised Kuramochi & Yamada’s “rhythmic parroting” as a memorable combination to this day. Unlike his TV Asahi counterpart Ichiro Furutachi, who was informed on angles in advance, Kuramochi claims that his reactions were genuine. Even in the case of May 2, 1980, which saw him attacked by the Sheik during a prolonged postmatch brawl against Abdullah the Butcher, Takao claims that only Baba and producer Akira Hara would have known about the plan. (Nippon Television declined to air the match for many years, while Kuramochi received a ¥200,000 bonus from the Babas.) Kuramochi also differed from Furutachi in his approach. Ichiro’s ten-year tenure for World Pro Wrestling set the template for the “screaming announcer”, a wildly successful style which anticipated later play-by-play men such as Kuramochi successor Kenji Wakabayashi. In contrast, Kuramochi preferred to convey his excitement through accelerating his speech to match the tone of the moment, allowing himself to be passionate but not histrionic. Kuramochi’s style may not have transcended language barriers in the manner that Furutachi and his successors could at their best, but that is hardly a fair metric to hold him against. Even if he may not have had a personal passion for wrestling, belonging more to a generation of television announcers that saw wrestling as a steppingstone to a job that they really wanted, he is fondly remembered by his native audience. Kuramochi retired from the program in 1990 to take a job at the network’s business division. He received a warm farewell at the March 6 Budokan show. While he took a job at parent company Yomiuri Shimbun a few years later, Kuramochi continued to work in the television industry until his 2001 retirement.

-

- ajpw

- commentator

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

These are some examples of how AJPW fans of the period would have encountered Yamada's writing. In the August 1974 issue of Monthly Puroresu, Yamada writes the second part of a serial about Jumbo Tsuruta. This serial was implied in a 1977 retrospective feature (for the magazine's 300th issue) to have been published to cater to Tsuruta's female fanbase. Yamada also wrote the ten-part 1973 serial "Fly, Jumbo!" and another 1976 serial about Tsuruta. In the pamphlet for the 1976 Champion Carnival tour, Yamada is credited for an obituary on Masio Koma. He also likely wrote an unattributed piece from the same pamphlet. It covers medical and physical tests that the rest of the roster undertook after Koma’s death, Tsuruta’s ascetic training before his match against Rusher Kimura, and the AJPW vs IWE show of March 28.

-

Takashi Yamada (山田隆) Profession: Commentator (Color), Reporter Real name: Takashi Yamada Professional name: not applicable Life: 5/24/1933-9/8/1998 Born: Kitami, Hokkaido, Japan Career:1967-1989? (as commentator) Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, All Japan Pro Wrestling Takashi Yamada was one of puroresu’s most reliable commentators in a two-decade career for Nippon Television. Takashi Yamada was an eight-year veteran of Tokyo Sports when he debuted as a commentator in November 1967. Yamada would spend the next two decades working as an assigned reporter and color commentator. Yamada was not the first wrestling reporter to moonlight as a commentator, but his ability to provide background and overseas information on foreign talent codified the role of the reporter-commentator in puroresu broadcasting. His work for AJPW is his greatest legacy, as besides announcer Takao Kuramochi he was likely the most consistent broadcast presence across its first fifteen years. Takashi’s husky voice will be familiar to any connoisseur of Showa period All Japan, although from personal observation, his voice is sometimes mistaken for Giant Baba’s by Western viewers. While it is hard to find classic calls from Japanese announcers the same way that one might learn about famous soundbites from American ones, Yamada’s shocked reaction to Stan Hansen’s presence in the 1981 Real World Tag League final has been cited by online fans as particularly memorable. Yamada accompanied the promotion on tour, which leads us to another part of his function. His writing was constantly read by active fans of All Japan, whether they knew it or not. This ranged from articles printed in tour programs to contributions to puroresu magazines, which often saw him uncredited or under a pen name. (These can generally be identified by the presence of one of the characters in his family name, 山田.) Yamada was phased out around the end of the Showa period. A one-off return for AJPW’s 20th anniversary show was the end of his broadcasting career. He died of cirrhosis in 1998.

-

Chapter Five This isn’t really worth doing a bullet list. Jumbo spends most of this chapter in a philosophical/motivational speaking mode, writing about his double life as Jumbo Tsuruta and Tsuruta Tomomi. He writes “wrestling is love”, which makes me wonder if Keiji Mutoh unconsciously plagiarized his fellow Yamanashi man when he started using “Pro-Wrestling Love” as a marketing term. There is one thing, though, that interests me. Towards the very end of the chapter, he writes: “I used to be a wrestling boy from Yamanashi. I was the one who ran frantically at eight o'clock on a Friday night. I was the one who cheered Rikidozan on the TV in the electronics store. Even now, I have not forgotten that feeling of excitement. I wanted to be like Rikidozan that day.” For just a moment, the real Tsuruta might have slipped through the cracks. In an episode of the podcast Write That Down!, Fumi Saito tells a personal story about Jumbo. When Tsuruta was AWA champion, Fumi was finishing his bachelor's at Augsburg University in Minneapolis, where he also washed dishes for a Chinese restaurant. He recalls that he would eat dinner with Tsuruta when he was in town, and claims that Tsuruta told him he had wanted to be a pro wrestler since the sixth grade. This is the only acknowledgement I've seen from Tsuruta that he had been a wrestling fan, but if we take what he said to Fumi as true, it recontextualizes some things. You will recall that in the Jumbo bio posts I wrote about Tsuruta's experience at a sumo stable in the summer of 1964. It is very plausible that a Japanese kid dreaming of becoming a pro wrestler in the 60s would want to get a taste of the sumo life. Perhaps even the idea of becoming an Olympian to transfer into pro wrestling occurred earlier than Jumbo ever let on, as Tsuneharu Sugiyama and Masanori Saito both entered the JWA after competing in the Tokyo Olympics.

-

Chapter Four The chapter starts with an interview segment, though it’s unclear if Tsuruta is interviewing himself. Tsuruta writes of going to his sister’s establishment with his coworkers. As the bio posts covered, Tsuruta was not much of a drinker, but he says that he likes the atmosphere. He notes that Kojika and Okuma are the heaviest drinkers, while Tenryu and Takashi Ishikawa were more about the atmosphere as well. (For as notorious a drinker as Tenryu would become, he actually claims that he was sober through the first chunk of his wrestling career.) He says he has played the guitar since he was a kid, inspired by the Beatles, but he didn’t get serious about the hobby until entering pro wrestling. He claims that, like Terry Funk, he wants to produce his own movie: a musical starring vehicle with a Rocky-like story and Elvis-inspired music. After the interview, Jumbo writes about music some more. His favorite artists: John Lennon, Elvis Presley, Yosui Inoue, and Takuro Yoshida. He almost played bass for a student band in high school. He fondly remembers seeing Elvis in Amarillo after winning his title back from Billy Robinson. He claims that he designed his trunks himself (these are the red and blue trunks with the three stars in the back). The stars are placed higher to make his legs look longer. However, he generally keeps his dress outside the ring simple. He contrasts the “dandy” Mil Mascaras with Kojika, Okuma, and Harley Race, who wear gaudy checkered patterns and make haphazard color choices. Jumbo talks about various celebrities he knows. In 1980, Tsuruta shot a commercial with actress, singer, and notable Moonie Junzo Sakurada. Jumbo met Momoe Yamaguchi at the CBS Sony studio, who said she liked wrestling and wanted to meet up sometime. He admits that he envies her husband. He has several actor friends, such as Ken Takakura, Jiro Hira, Hayato Tani, Kinya Kitaoji, and Koji Takahashi. He states that he often works out with them. He talks about appearing on the radio show of Taku Baimura, and hitting it off with him. He told Baimura that he liked to read the novels of Ryotaro Shiba. (Tsuruta deeply admired the mid-19th century revolutionary Ryoma Sakamoto, about whom Shiba wrote a very famous series in the 60s. Ryoma Goes His Way has been credited with increasing Sakamoto’s presence in popular culture.) The blonde woman who was frequently seen in the front row of 80s AJPW shows is identified as Baba fan Edith Hanson. The daughter of Danish missionaries in northern India, Hansen had been a television personality in Japan since the sixties. Jumbo writes a bit about his experiences with women. He does not allude to his relationship with Yazuko Aramaki, which had recently ended (of course, they were far from finished with each other). He does recall trying to date a blonde girl during his time in Amarillo…but that damned Baba kept making sure that he wasn’t getting too involved with any girls. (If this is true, I’m wondering if Baba was fearing a Diana Inoki situation. Masanori Toguchi eventually left All Japan over their refusal to cover the costs to fly his family over to see him wrestle, so perhaps Baba wanted to make sure his top prospect didn’t become too domestically rooted.) Jumbo does state, though, that he would prefer to marry a Japanese woman. In the span of two pages, Jumbo goes from making a dad joke about having to win a "jumbo lottery" to find his ideal mate, to recalling that he went through a Kierkegaard phase in high school. What a guy. He also talks about his great admiration for the aforementioned Ryoma Sakamoto.

-

I promise that Chapter Four has more interesting stuff to note. Chapter Three Jumbo writes that Baba told him the plan to have the two of them challenge for the Funks’ tag titles on an international call from Hawaii. Other ring names that were considered in the fan poll were Tiger Tsuruta (I’m guessing this was a reference to Takeda Shingen, who was known as the Tiger of Kai), Hurricane Tsuruta, and Iron Tsuruta. Tsuruta confirms what I could tell from his facial expressions before his Trial match against Verne Gagne; the news of Koma's death, which he had received that morning, had hit hard. A section of this chapter shows the rationalization that puroresu kayfabe had developed for the carny shit. He never says it's a work, but pro wrestling is painted as an entertainment event first. A wrestler needs to have "thrilling" matches in order for wrestling to attract an audience. (Jumbo doesn't go into this aspect, but in the Pillars book, Ichinose tells an anecdote about talking to a taxi driver who saw that wrestling was fake. As he explained it, the guys really are trying to win, but they're not trying to hurt each other, because it would hurt their bottom line if wrestlers got injured all the time. I'll admit, this makes old puro angles like "Tiger Jeet Singh breaks Strong Kobayashi's arm to win the tag titles by forfeit" a bit more compelling.)

-

Chapter Two Jumbo's first NWA title shot, 5/20/1973. Tsuruta tells the story of what drove him to join AJPW, which is basically what was written in the 2020 biography minus the details about Akio Nojima. He claims his mother protested, thinking her baby boy was too soft and sweet to be a pro wrestler. After eating dinner with his AJPW coworkers in a restaurant at the airport terminal, Tsuruta entered the lobby to find his Chuo University teammates there to see him off. When Tsuruta arrived in Amarillo, he was expecting to find referee Ken Farber to pick him up from the airport. He waited for half an hour, slowly building to a panic over his weak English and inability to afford a return trip. As it turned out, Farber had been ribbing him the whole time, watching from the restroom door. (Tsuruta claims that Tenryu got the same rib when he first arrived, but in his case it went on for a whole hour.) Tsuruta does not mention Dory Funk Jr.’s version of events, which was that they first met at a TV taping on which Dory, assuming Tsuruta was experienced, had already booked him. He claims that Dory Sr. hated the Japanese and did not have high expectations for him, but that Junior had his back. This is definitely contradicted by other accounts. First of all, Senior was the one who stuck his neck out for Baba and used his leverage as the champion’s dad to push the NWA general meeting from August to February. (This was in the brief period when NJPW was planning to merge with the JWA, so Baba needed to get into the NWA before the fiscal year ended.) He also reportedly remarked of Tsuruta that he already had everything he needed to be a top wrestler. Tsuruta claims that Terry was a speed freak: “We drink beer, make a lot of noise, and fly down the highway late at night, because if we don't, we will fall asleep. Otherwise, you will fall asleep. The Highway Patrol may be chasing us, but we don't give a damn! We are more than happy to have thrilling car chases!” Also, Terry would often sleep with his tights on. He also writes that Terry would stay in his hotel room after shows and work on a screenplay for a “cowboy love story” starring himself. Dory, meanwhile, was the calm, collected “philosopher”. For all their differences, though, they would both sing country songs at the top of their lungs when they were at the bar. (As a tag team, Tsuruta makes a sumo analogy, comparing Dory to the strong, firm Taiho, and Terry to the vigorous, agile Chiyonofuji.) The Amarillo wrestlers’ diet mostly consisted of Mexican food and KFC. Dory advised Jumbo to lean into his Japaneseness in his performances, which explains his greater tendency to use chops when wrestling in the States. Tsuruta claims that Bob Backlund was one of the wrestlers he worked alongside during this time, but it is known that their paths did not actually cross until Tsuruta’s second excursion in early 1974.

-

Ringu Yori Ai O Komete (“With Love From The Ring”) is a 1981 autobiography by Jumbo Tsuruta. At just over 200 pages, the book is an interesting snapshot of the kayfabe around the wrestler as he turned thirty. My series of posts on the 2020 biography by Kagehiro Osano already covers much of this, and for the most part I’m not going to repeat that stuff here. Think of this thread more as fun flavor text. There are six chapters, and I have transcribed all but the last, which appears to be largely poetry. (Note to Loss: This stuff is light enough that I don’t think it warrants a new thread for each post like the aforementioned bio.) Chapter One Tsuruta gives the kayfabe version of his birth, which goes that he was named Tomomi because he seemed small. He gives a little info about his mother’s first marriage. She bore two children to a man who “drank wine all day” and got on very badly with her mother-in-law, until she walked back home to her father and cried. Many years later, Tsuruta would meet his half-sister Toshiko, who he claims asked to see him backstage at a show. (Tsuruta would support her bar, Champion, with free advertising; I recently tweeted a photo of him there.) In the modern day, Tsuruta claims that his mother becomes “like a child” when she watches wrestling, shouting at the top of her lungs: “Tomomi! Go for it! Suplex! That's right, hit him! Go! Ref, count, count, count! Count!" However, when he asks her favorite wrestlers, she basically names everyone but him, then says “I don’t like how the Yamanashi boy is acting” when he asks what she thinks of him. His father was a veteran. (Tsuruta repeats the story that he died the day after his son returned from Munich, which Osano debunked.) Tsuruta recalls wanting to be like Takeda Shingen, the 16th-century warlord who was born in his native province, when he was a child. Tsuruta directly references Shingen’s famous Fūrinkazan banner—which literally reads “Wind, Forest, Fire, Mountain", but is understood as shorthand for the line "as swift as wind, as gentle as forest, as fierce as fire, as unshakable as mountain” from The Art of War —and claims he thought of it to calm himself during his first flight to America. Possibly relevant cultural context: this book was published a year after Akira Kurosawa’s film Kagemusha, a historical drama about a criminal doppleganger of Shingen who is forced to impersonate the dying warlord. The Fūrinkazan banner is shown prominently in the film’s powerful ending, sunk in the river. Tsuruta claims that he is haunted by an incident where he fell asleep on top of a cat and suffocated it when he was a teenager. He recalls that he was locked in the barn one night without food for skipping on his farm duties (cutting grass for the cows). His first love was a classmate in fifth grade. So smitten was he that, when he was at their school for a summer track and field training camp, he snuck into their classroom one night. He wrote her name on the chalkboard, and took her seat cushion to use as a pillow. Now, he thinks that was strange, but at the time it made him feel happy and excited. This story ended in humiliation, as he was forced to sit across from her for lunch one day. Too nervous to eat until the girl next to him asked why, Tsuruta grabbed his milk…only to pour it into his nose. Tsuruta’s first year of college coincided with lengthy student protests. He still practiced basketball, but there were no classes. It was a time where he felt guilty over choosing to go to college, as his family was bearing this financial burden when he had so little to show for it. Tsuruta tells one lie about the Munich Olympics that bothers me a little. I believe him when he writes that the Black September attack was a traumatic event. However, he claims that he had been scheduled to wrestle one of the men who was killed. Neither of the two Israeli wrestlers who were killed, Eliezer Halfin and Mark Slavin, competed in Tsuruta’s division. This is the one passage of the book that makes me wish it was ghostwritten, although I could not find any compositional credit. On a lighter note, even a light drinker such as Tomomi could not go to Munich without a taste of beer. However, he was so taken by the beautiful blonde woman who served it that he spilled it on his lap. Tsuruta then comments that the Moscow Olympic boycott had been a great shame. (His future tag partner, Yoshiaki Yatsu, would most certainly agree.)

-

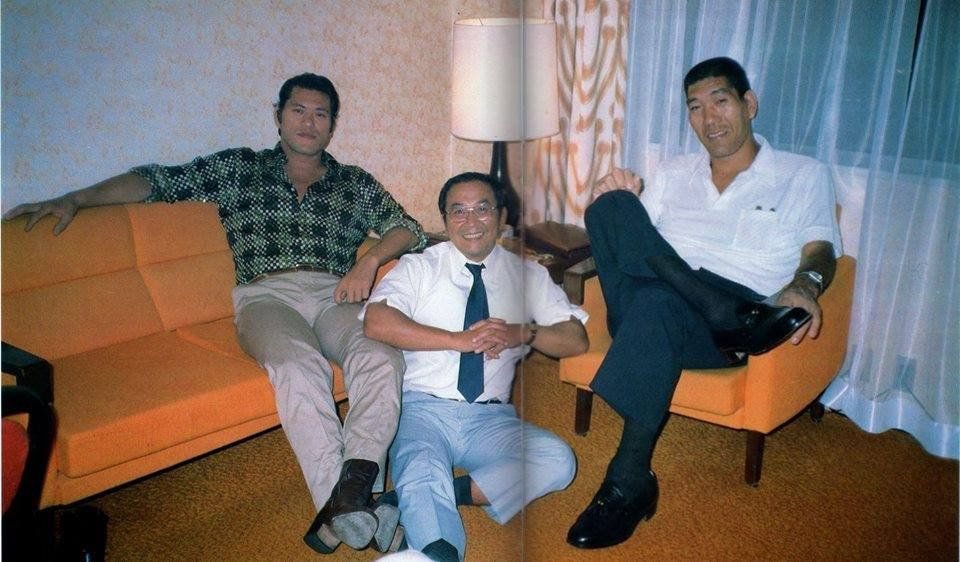

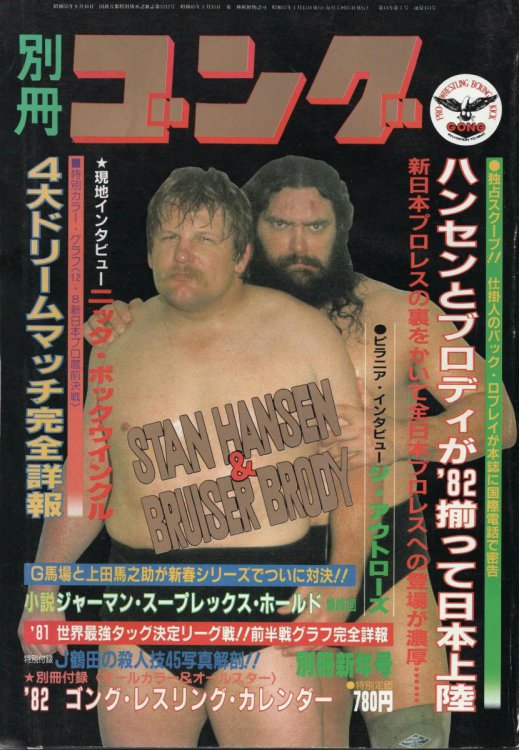

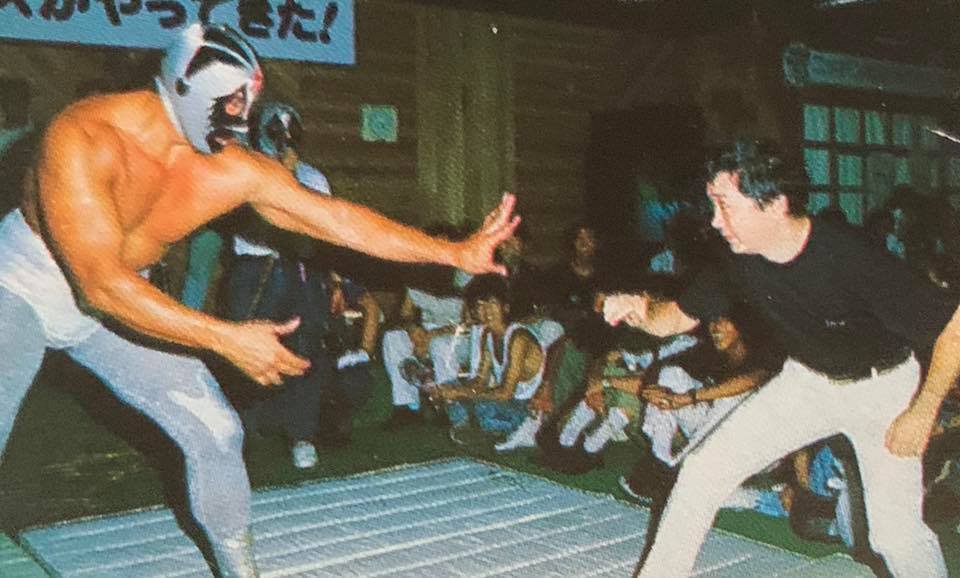

I have revived my plan to write a piece on From Milo to Misawa about Kosuke Takeuchi and the legacy of Gong magazine, which will be published on May 3, the tenth anniversary of his death. In the meantime, I have decided to publish the first part of the article, which essentially covers the Monthly era of the magazine while also revealing Takeuchi's legacy as an archivist. (I've picked a few alternate photos to make this version a little unique.) ---- EARLY YEARS Left: A caricature of the first match Kosuke Takeuchi saw, published in the second-ever issue of Monthly Puroresu. It was on a summer night in 1955, on a street television in the Taito ward, that Kosuke Takeuchi first saw pro wrestling. Retired yokozuna Azumafuji was set to debut for Japan Pro Wrestling at the Kuramae Kokugikan.. His match would see him brutalized to a disqualification victory against Jess Ortega, before Rikidozan ran into the ring and fought off the Mexican Giant with his chops. In a microcosm of how Rikidozan’s myth fed off of his supersession of native martial arts, Takeuchi didn’t care about Azumafuji after that, but Rikidozan’s image was seared into his mind. Takeuchi remained a loyal viewer through JPW’s first decline, trading the small street set for the TV inside a local yakisoba restaurant. As the promotion began its rebound, he would attend his first show. Mr. Atomic, a masked wrestler concocted by sales manager Hiroshi Iwata as a response to tokusatsu sensation Gekko Kamen, got two shots at Rikidozan’s International Heavyweight title in the summer of 1959. When Takeuchi learned that JPW’s show at the Denen Coliseum would admit children for just 50 yen, he bought a map and navigated to the Ota ward venue. By high school, Takeuchi regularly attended shows at the Riki Sports Palace in Shinjuku, and had a chance encounter with Professional Wrestling & Boxing editor-in-chief Yukio Koyonagi. Koyonagi got in touch a few months later. Before he had even completed school, Takeuchi was hired as a photographer in 1965. He quickly grew weary, as PWB was a stale product closer in its coverage to a newspaper than a magazine. He decided to apply for a position at Toyonobori’s new promotion, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, and came to the offices of parent company Baseball Magazine (BBM) to turn in his resignation. Koyonagi wanted to know why. When Takeuchi admitted that he was dissatisfied with their product, Koyonagi asked if he thought he could make it better, and when Kosuke answered in the affirmative, he promoted him on the spot. He would also become EIC of sister magazine Monthly Bodybuilding. However, neither man was long for their parent company. After BBM struggled with bankruptcy in 1967, Koyonagi jumped ship to help form Nihon Sports Publications. He then scouted Takeuchi, who quit his post to head a new magazine. EARLY YEARS OF GONG Gong debuted in March 1968. Like its competitor, Gong also covered genuine combat sports, although sister magazine Monthly Gong, debuting in 1969, exclusively featured wrestling. Takeuchi’s passion for graphic design would shine in Gong‘s vibrant covers, and the magazine would also be the first to feature color photography within its pages. I cannot speak articulately about early Gong‘s textual content with relation to its competitor. Dave Meltzer’s Takeuchi obituary sums it up as the Japanese equivalent of a Stanley Weston magazine, relatively embellished compared to the Norman Keitzer-esque coverage of PWB and Monthly Puroresu (to which the former rebranded in 1972). However, as Fumi Saito has pointed out, puroresu journalists were printing the proverbial legend from the start; Hiroshi Tazuhama’s pioneering coverage was responsible for such embellishments as Rikidozan’s bar fight with Harold Sakata (after which the two had supposedly bonded and Sakata had gotten Rikidozan booked on the Torii Oasis Shriners Club tour). Even the handful of late-70s Monthly Puroresu issues that I own, which I have debound and scanned for selected transcription, contain novelized “Turning Point” columns written from wrestlers’ perspectives, although this may reflect the influence of early Gong. Here is what I do know, mainly sourced from the recollections of Kagehiro Osano in a 2016 interview with Dropkick magazine. Tokyo Sports reporter Yasuo Sakurai made many contributions, although Osano doubts the veracity of his overseas match reports (“[I think] he was writing from the photographs”). The magazine connected fans to wrestlers with features ranging from the “My Privacy” column to reader-submitted questions. Gong also featured content by Shigeo Kado, the Tokyo Sports reporter-turned-JPW Commission secretary general. While his interests may have given his material the whiff of the party line, Kado also had an unusually strong “sense of exposé” for his time. Osano particularly recalls Shishi to Ryu (“The Lion and the Dragon”), a serialized feature about Baba and Inoki’s rivalry which would have been “disillusioning” for a child to read. Takeuchi himself claimed that his desire to produce content about Rikidōzan, which had been suppressed by the BBM higher-ups, would finally be satiated with Gong. If my aforementioned copies of Monthly Puroresu are anything to go by, such retrospective content became commonplace. When one speaks about Gong, though, there is one wrestler that is central to its legacy, and I am perfectly equipped to speak on this. AKUMA KAMEN In one of his final interviews, Takeuchi recalled that he wanted to find “a hero” for Gong: a vibrant wrestler through which he could capitalize on his industry’s shift towards color. He would find his man virtually immediately. Takeuchi first learned about Mil Máscaras from Sakurai. Máscaras had spent five years in the business and had already started his Mexican film career when he made his US debut that spring. He quickly became a sensation in Los Angeles. Tokyo Sports foreign correspondent Sakae Yoshimoto sent Gong photos of Máscaras, and a legend was born. (Meltzer claims the photography of Dan Westbrook was used, which may well be true, but Tsutomu Shimizu states that Yoshimoto shot the first Máscaras photographs in Gong.) Over the next three years, Máscaras would appear in Gong nearly 50 times. It wasn’t just that he was a vibrant subject for color photography, though. Even if Máscaras’ style was relatively grounded, it was downright exotic to a fanbase whose notion of a Mexican wrestler would have been Jess Ortega. Just as 1968 was the year that the IWE’s relationship with George de Relwyskow Jr. brought British wrestling to Japan, it was the year that Máscaras coverage gave glimpses into the rich world of lucha. In 1970, Takeuchi’s work to showcase Máscaras paid off. The IWE, emboldened by their new connection to the AWA, held a poll to scout interest in wrestlers who had not yet worked in Japan. Máscaras came in second place, with less than fifty votes between him and winner Spiros Arion. After months of sabotage and counteroffers, Máscaras and Arion would work for JPW in March 1971, where Mil received a disproportionate amount of attention, to Arion’s resentment. During his time in Japan, he visited Gong‘s offices. Tsutomu Shimizu had been captivated by Máscaras since his first Gong appearance. The 14-year-old Tokyo native would not be able to see Mil’s Japanese debut on February 19, in which he defeated Kantaro Hoshino in Korakuen Hall. One week later, though, JPW ran Korakuen again, and Shimizu saw Mil go over the Great Kojika in the semi-main. Máscaras would work two more tours for Japan Pro Wrestling until their closure in 1973. That year, as Shimizu formed the fan club Akuma Kamen (Devil’s Mask), Takeuchi persistently requested that Giant Baba book Máscaras for All Japan Pro Wrestling. Baba’s general antipathy towards lucha talent would hardly thaw overnight, but Máscaras debuted for AJPW in the 1973 Giant Series. On October 9, the same night that Tomomi Tsuruta would become a star, Máscaras began his first great rivalry in Japan against another masked wrestler with history in Los Angeles: the Destroyer. Máscaras’ Japanese popularity waned in the mid-1970s, but Shimizu continued to run his club as he enrolled at Wako University in 1975, eventually renaming it El Amigo. Even this early, Takeuchi would support him by giving him interview opportunities. Shimizu stands second from left as El Amigo is featured on the show Good Morning in July 1978. On his right is future Universal Lucha Libre announcer Tera Hanbay. 1977 would begin Máscaras’ golden age in Japan. AJPW television director Susumu Umegaki was inspired to use Jigsaw’s “Sky High” as Máscaras’ entrance music. This wasn’t the first time that puroresu had used entrance music; the IWE’s television director had done so for Billy Graham in 1974, and Umegaki himself had experimented with music for Jumbo Tsuruta as far back as 1975. However, “Sky High” was where the trend took off, with a tie-in single racing up the charts; before the year had ended, AJPW had enough entrance music to release a compilation album, The Great Fighting. The success of Umegaki’s experiment culminated on August 20, 1977. In the Denen Coliseum, where Takeuchi had seen Mr. Atomic many years before, Gong‘s “hero” challenged Tsuruta for his NWA United National title. Kosuke did his part by deploying the members of clubs such as Shimizu’s as cheer squads. When Máscaras returned in 1978, alongside his younger brother Dos Caras, Takeuchi began work as a guest commentator for his matches. However, Takeuchi was not a partisan supporter of All Japan, as he also had an excellent relationship with NJPW sales manager and strategist Hisashi Shinma. Just a month before his first appearance at the All Japan commentary booth, Takeuchi had provided his services for their chief competitor. NJPW had convinced the IWE’s Ryuma Go to leave and work for them as a freelancer, as Shinma wanted to capitalize on Tatsumi Fujinami’s popularity by creating a junior heavyweight version of the Inoki vs. Strong Kobayashi matches of 1974. The likes of El Amigo, Ashura Hara club Wild Child, and New Japan fan club The Flame Fighters, headed by Kagehiro Osano, were assigned to cheer each man. TAKEUCHI TAPES “He was smart, rich, and had all the latest electronics. He had a new VCR and a new stereo.” Kagehiro Osano A large part of Takeuchi’s appeal to young superfans is now possibly his greatest legacy, hidden in plain sight, as puroresu’s earliest archivist. An early adopter of the VCR, Takeuchi extensively taped the television programs of his day. Over the decades, a substantial amount of this footage would circulate into trader circles. As official efforts to recirculate archival footage are inevitably compromised by their nature as low-effort filler for satellite stations, or the occasional DVD set, the Takeuchi Tapes have become our only sources for many significant matches, from Tokyo Sports’ 1978 Match of the Year (Jumbo Tsuruta vs. Harley Race) to numerous title defenses. Consider how, despite the fact that Nippon Television aired JPW material for over fifteen years, almost all of that which circulates today is descended from eighteen hours of material collected in 1972. Consider that the full year of AJPW which aired prior to Tsuruta’s debut has been mercilessly slashed, quite likely forever, to the contents of two episodes from December 1972 and April 1973. Consider that only three matches from Antonio Inoki and Seiji Sakaguchi’s original run as NJPW’s top tag team circulate today (and that one of those, the August 1973 match in LA against Pat Patterson and Johnny Powers, isn’t available outside of an episode of Sky-A Classics). Consider how much of the IWE’s TBS run only survives in 8mm fragments. For as unremarkable and even tedious to modern eyes as the Takeuchi Tapes may reveal 70s puroresu to have often been, a survey of all we lost before should suffice to appreciate them. Furthermore, a claim that Takeuchi possessed footage of the untelevised 1985 Real World Tag League match between the teams of Riki Choshu & Yoshiaki Yatsu and Giant Baba & Dory Funk Jr. indicates that Kosuke’s archive extended to audience recordings and implies that he may have been a hub for the exchange of such material. To explain why I believe this, I need to move along. As the decade neared its end, Takeuchi organized a new fan club: the Maniax. In the beginning, there were four official members: Shimizu, Kiyonori Shishikura, Jimmy Suzuki, and Yusuke “Wally” Yamaguchi. Suzuki has referred to the Maniax as a “reserve force” for Gong, as they contributed to the magazine long before any were officially hired. With the exception of Beantank (Kotetsu Yamamoto) founder Masahiko Takasugi, who would become an IWE trainee, none of the superfans from this generation would enter the ring themselves, but several entered journalism. The Maniax also made and screened 8mm film recordings, which Shimizu has admitted they could never get away with now. (At right are invitations to the 1978 and 1979 screenings, which were given to Tera Hanbay.) It’s a damn good thing they did, though, as Takeuchi would supply some of this footage to an IWE box set in the mid-2000s, when television tapes could not be found or did not exist. Whether or not any of the people involved would admit it, I think it’s plausible that Takeuchi may have had some role in the proliferation of early fancams. TAKEUCHI ENDS THE PULLOUT WAR In December 1980, Takeuchi left Nihon Sports Publications and his editor-in-chief position to become an editorial advisor to Gong instead. He would be replaced by Shotaro Funaki, who had overseen its combat sports coverage. These two had long been the only contracted employees of Gong‘s editorial department, but in this decade that would change. As the first generation of Maniax embarked on overseas training, not unlike the wrestlers they covered, the last great story of the Monthly Gong era unfolded. 1981 was the year of the “pullout war”. NJPW had fired the first shot, swiping Abdullah the Butcher, Dick Murdoch, and Tiger Toguchi (who would revert to his Korean name of Kim Duk) to coincide with the formation of the International Wrestling Grand Prix. AJPW had retaliated by taking Tiger Jeet Singh and Umanosuke Ueda, and Baba managed to secure a top-secret meeting with Stan Hansen, who had been NJPW’s top gaikokujin since the previous year. Hansen would continue to work with NJPW for the rest of 1981 while delaying his decision to renew his long-term deal, to Shinma’s exasperation. As was revealed in one of puroresu’s all-time great angles on December 13—in which Hansen accompanied Bruiser Brody and Jimmy Snuka to the RWTL final against the Funks, tipping the scales their way in a pivotal bit of interference—Hansen had indeed switched sides. What made the cover of Gong that you see on the right so controversial? It would have to be produced before the angle actually happened. At some point, Terry Funk had confided in Yamaguchi that Hansen was coming. This information, if it were true, would have to remain in Takeuchi’s proverbial chamber until the last possible moment. If he tipped his hand, NJPW would surely move heaven and earth to keep one of their biggest stars, and his magazine’s relationship with Baba may have been tarnished. So, he waited, and waited, and he would be rewarded with the photograph you see. It was shot in New Orleans by overseas reporter Kiyoshi Ibaraki, and it led Takeuchi to surmise that AJPW was planning a Brody-Hansen team. Still, though, it wasn’t time, so Takeuchi hid the film in a drawer. Finally, on December 10, Takeuchi decided it was time. He asked both Brody and Hansen for comment. Brody said that he “couldn’t give any details yet”, but that he believed they would be in the same promotion in the next year, while Hansen denied it, dismissing it as “just what Frank wanted”. Two days later, though, Hansen would make a shocking appearance at AJPW’s Yokosuka show, where he asked to talk with Frank and was escorted backstage by Joe Higuchi. Gong hit the shelves on the 17th. The timing was perfect: *too* perfect, some believed. Monthly Puroresu published an interview with Seiji Sakaguchi in their February 1982 issue, which came out on January 14. Sakaguchi remarked that “one part of the media had secretly maneuvered about Hansen’s withdrawal”, as it appeared that Takeuchi had been in on the transfer, having managed to take a photo of the two together. He immediately met with Sakaguchi and explained that he had held onto the photo for months, but Gong‘s competitor maintained that they must have been in on it. In order to clear his name, Takeuchi had to do something big. He offered to mediate a secret summit meeting between Baba, Inoki and Shinma, and they took him up on it. Baba and Inoki each had a Tokyo hotel in which they held press conferences and clandestine meetings. Baba’s was the Akasaka Prince Hotel, while Inoki’s was the Keio Plaza Hotel. This time, though, they booked a room at the Imperial Hotel. The three men hashed out an informal agreement to end the pullout war, and naturally, Gong got the exclusive scoop. It may be the greatest vindication of Takeuchi’s cooperative approach as a wrestling journalist. Alas, puroresu journalism would move towards a much different path. The 1982 summit meeting.

-

This post cannot be displayed because it is in a password protected forum. Enter Password

-

This post cannot be displayed because it is in a password protected forum. Enter Password

-

Apollo Sugawara (アポロ菅原) Real Name: Nobuyoshi Sugawara (菅原伸義) Professional Names: Nobuyoshi Sugawara, Kim Korea, Apollo Sugawara Life: 2/10/1954- Born: Oga, Akita, Japan Career: 1979-2002 Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise, All Japan Pro Wrestling, SWS, NOW, Tokyo Pro Wrestling (Ishikawa) Height/Weight: 182cm/111kg (6’/244 lbs.) Signature Moves: Back flip (Samoan Drop variant) Titles: none Apollo Sugawara was the least accomplished of the final batch of IWE trainees, but he has an interesting legacy as a journeyman wrestler and coach. Nobuyoshi Sugawara was an amateur wrestler in high school, winning a prefectural competition and placing fourth in nationals. Upon his graduation, Sugawara began work at a Chiba shipyard. In 1979, he was recommended to the International Wrestling Enterprise by the owner of his gym, Japan Bodybuilding Association president and IWE referee Mitsuo Endo. Joining in May 1979, Sugawara debuted in September. Alongside Hiromichi Fuyuki and Masahiko Takasugi, Sugawara was one of the last wrestlers the IWE produced before their dojo was burned down in 1980. He claims that he received no salary. Upon the IWE’s closure, Sugawara and Fuyuki were taken in by All Japan Pro Wrestling under the wing of Mighty Inoue. (Takasugi would join them later after a Mexican excursion.) This influx helped make the AJPW undercard talent pool the deepest it had ever been, alongside homegrown prospects such as Shiro Koshinaka, Tarzan Goto, and Mitsuharu Misawa. In retrospect, Sugawara has admitted that he never had a chance of getting to the top. In April 1983, Sugawara entered the undercard Lou Thesz Cup tournament. The following September, he traveled to Germany to work for Otto Wanz, alongside fellow IWE alum Goro Tsurumi. As CWA already had billed Tsurumi as the Japanese Goro Tanaka, Sugawara was instead billed as Kim Korea. Upon his return to All Japan, Sugawara joined the reconfigured Kokusai Ketsumeigun, a heel faction of ex-IWE wrestlers headed by Rusher Kimura. It was at this point that he took the Apollo ringname. Sugawara was cut in April 1986 alongside Ryuma Go and Masahiko Takasugi (and referee Mr. Hayashi). Ostensibly, this was a cut to make room for the Calgary Hurricanes: however, Goro Tsurumi claimed in a G Spirits interview that, during dinner one night, Sugawara had denigrated Baba in response to criticism. (Sugawara denies this, claiming he never would have talked back to Baba and that they never even ate together.) Unlike Go and Takasugi, who were hired on a per-tour basis in mid-1987, Sugawara never returned to AJPW. Sugawara’s next involvement in the business was as a coach for Takeshi Puroresu Gundan, a side project of comedian Beat Takeshi (Kitano) which tied into the infamous NJPW angle that introduced Big Van Vader to the latter. Under Sugawara’s guidance, the future Gedo, Jado, and Super Delfin all received their first training, in a ring which Wally Yamaguchi had set up in the basement of his Maniax wrestling merch store. In 1988, Sugawara reunited with Go and Takasugi to form Pioneer Senshi, the first shot in the indie boom. Sugawara and Takasugi wanted to name it Shin Kokusai Puroresu - that is, the new IWE - but Go vetoed this, due to his shame over having taken NJPW's offer in 1978. ("Pioneer" was itself a reference to their former home, which had used the word as tour branding.) Sugawara would only work on Pioneer’s first show in April 1989. Mitsuo Endo would hook Sugawara up with a gig as a wrestler and as Koji Kitao’s personal coach, but he would follow Kitao to SWS. Sugawara’s tenure is best known for a debacle of a match with Minoru Suzuki. (That same night, Kitao would have his infamous incident with John Tenta.) Sugawara remained with SWS until its closure, then bounced along from NOW to Shinsei NOW to Tokyo Pro Wrestling. While he has never officially retired, Sugawara’s last match was for IWA Japan in 2002, in which he tagged with Takasugi to defeat Steve Williams and Gypsy Joe.

-

Kokichi Endo (遠藤幸吉) Profession: Wrestler, Executive, Commentator (Color) Real name: Kokichi Endo Professional names: not applicable Life: 3/4/1926- (presumed alive) Born: Kanai (now Yamagata City), Yamagata, Japan Career: 1951-1966 Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association Height/Weight: 180cm/125kg (5’11”/275 lbs.) Signature Moves: Dropkick Titles: NWA World Tag Team Championship (1x, w/Rikidozan), Pacific Coast Tag Team title (1x, w/Rikidozan) Summary: Kokichi Endo was one of the JWA's most prominent early figures, most notably working as Rikidozan’s tag partner in the mid-fifties. Besides this, Endo is best known for his later executive role. Left: Endo and Rikidozan with singer Hibari Misora. Kokichi Endo was a founding member of the International Judo Association, a short-lived professional judo promotion that is regarded in some ways as an antecedent of the JWA. About a year after the Association’s final show, Endo and fellow judoka Yasuyuki Sakabe entered pro wrestling, as one of the Japanese athletes given a crash course by Bobby Bruns for the 1951 Torii Oasis Shriners Club tour. He toured overseas with the Great Togo in 1952, before returning home to become one of the JWA's charter members. He was Rikidōzan's opponent for an exhibition match at the completion ceremony for the Rikidōzan Dojo on July 30, 1953. In August 1954, Endo tagged alongside Rikidōzan to win Hans Schnabel & Lou Newman's fictitious Pacific Coast tag team titles; two years later, they had a program with the Sharpe brothers which earned them a fifteen-day reign with the NWA World Tag Team titles. Alongside Toyonobori, Yoshinosato, and Michiaki Yoshimura, Endo was one part of the executive council promoted after Rikidōzan's death. By that point, he was the last remaining wrestler to have worked the promotion's first show. While retiring from the ring in 1966, Endo remained a top executive as the accounting manager until the 1971 coup. According to a 2018 Weekly Fight article, he spoke the best English of all the senior executives. As for his politicking, though, he had mixed results. On one hand, his efforts to block Isao Yoshiwara from purchasing the Riki Sports Palace for the company led Yoshihara to form the competing International Wrestling Enterprise. On the other hand, Endo was the one who made the JWA's second network deal with NET (the future TV Asahi) possible, as he planted disinformation in a Tokyo Sports article, which exaggerated the threat of the Great Togo's would-be third promotion, in order to convince Nippon Television to let them shop for a second deal. Right: Endo (right) and Yoshinosato pose with Sam Muchnick in August 1967. NET's World Pro Wrestling saw Endo debut as a commentator. This kept him involved in the business after his dismissal in the 1971 coup attempt. He would continue in this capacity through the early years of the NJPW era of the program. By all accounts, he wasn’t very good at it. However, Endo's history with Mike LeBell made him a net positive for New Japan, connecting them to the Los Angeles territory. He also served as a referee for Inoki’s February 6, 1976 match against Willem Ruska. After the match, though, he blocked Ruska’s angry attempt at a judo throw, which exposed Ruska. He continued to appear onscreen as late as the following year, including as a commentator, a judge for the Ali fight, and the recipient of an attack by former valet Umanosuke Ueda in a memorable backstage segment. On December 13, 1979, Endo returned to referee Ruska's match against Seiji Sakaguchi; that, to my knowledge, was the end of his appearances. In a serialized interview with NJPW salesman Naoki Otsuka in G Spirits magazine, interviewer Kagehiro Osano remarks that Endo promoted shows in the Kanagata area.

-

JAPAN PRO WRESTLING, PART ONE (FORMATION AND NJPW SPLIT)

KinchStalker replied to KinchStalker's topic in Japan Pro Wrestling

Necroposting here, but it turns out you were right on the money. A feature from Monthly Puroresu (March 1982) reveals that it was romanized as Anton Hi-Cel. -