-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

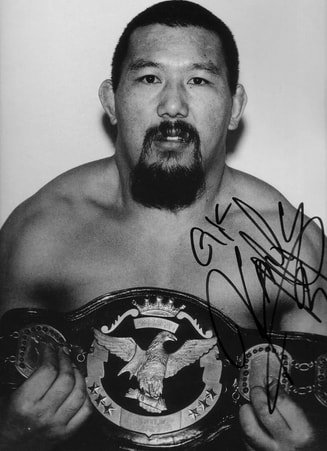

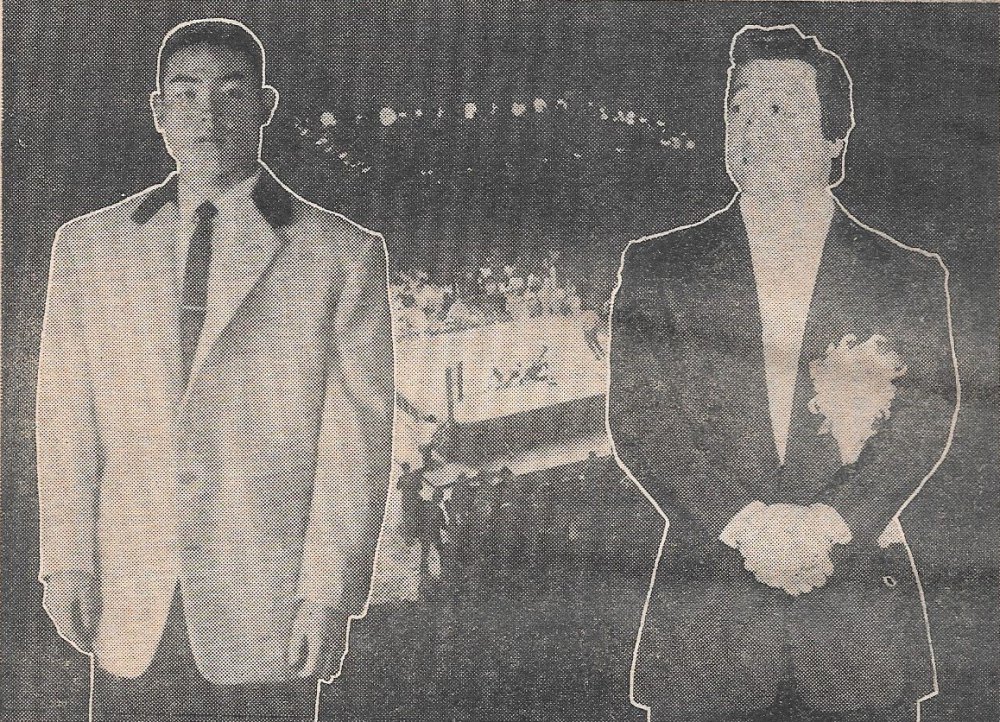

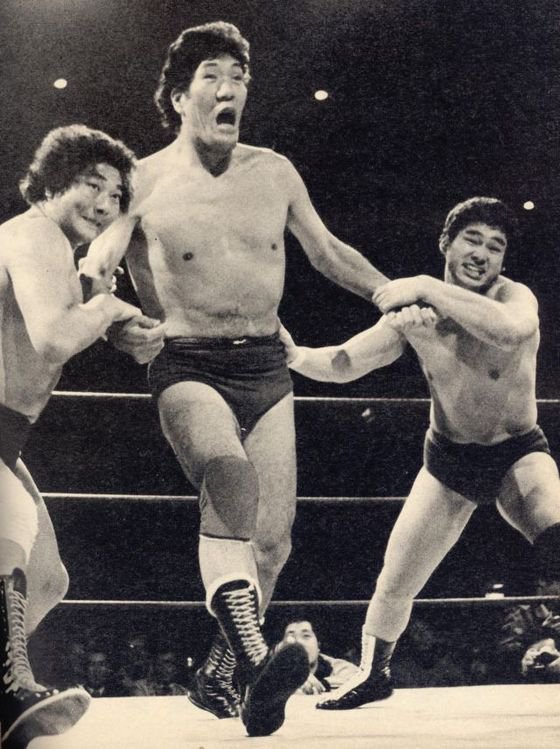

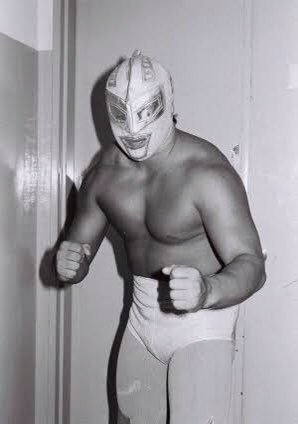

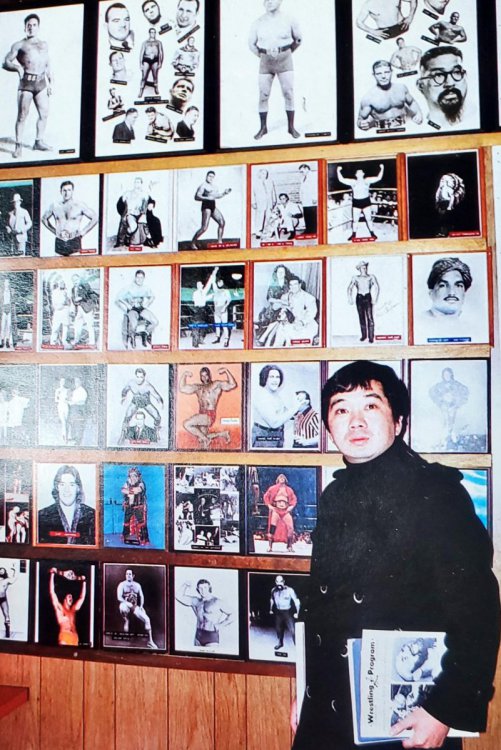

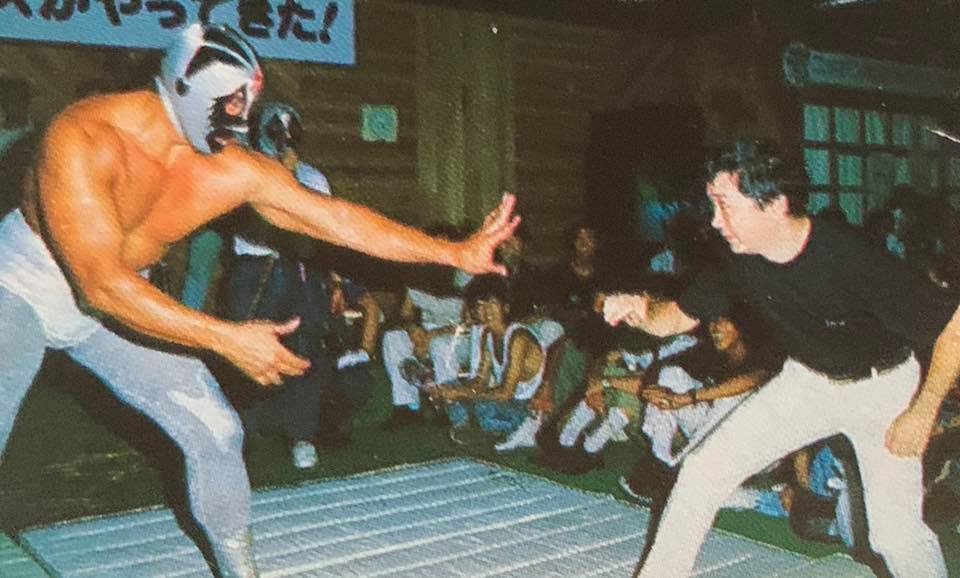

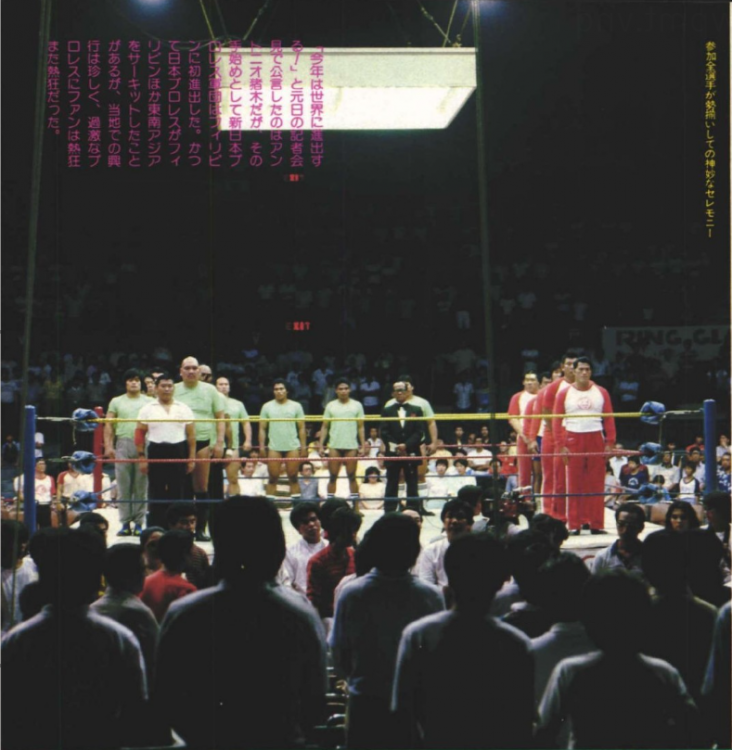

Masahiko Takasugi (高杉正彦)/Ultraseven (ウルトラセブン) Profession: Wrestler, Promoter Real name: Masahiko Takasugi Professional names: Masahiko Takasugi, Ultraseven, Super Seven Life: 6/17/1955- Born: Hiratsuka, Kanagawa, Japan Career: 1977- Height/Weight: 175cm/110kg (5'9"/242 lbs.) Signature moves: Flying crosschop, backdrop, hip attack Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise, All Japan Pro Wrestling, Pioneer Senshi, Shonan Pro Wrestling Titles: none Masahiko Takasugi was one of the IWE’s last significant products and became an early indie pioneer. He is also notable for wrestling under a gimmick based on Ultraseven. In the 1970s, a generation of puroresu superfans expressed their passion through the first fan club boom. If these fans made wrestling a part of their professional life, they generally did so through puroresu journalism, and nearly all of them through Kosuke Takeuchi’s Gong. These included the likes of Tsutomu Shimizu, Jimmy Suzuki, and Kagehiro Osano. Now, this wasn’t the only way that this generation entered the business; look at Universal Lucha Libre announcer Tera Hanbay, who had been a member of Shimizu’s El Amigo club in the 70s. But none of them ever dared to lace up a pair of boots. None, that is, except Masahiko Takasugi. Takasugi was an avid fan who attended shows by the JWA, IWE, NJPW, and AJPW in his youth. His club was Mametank (“beantank”), dedicated to the Yamaha Brothers. After playing gridiron football during his time in university (I found contradictory claims as to whether he graduated or dropped out), Takasugi applied for the IWE; he had been connected to them through working out at the Yokohama Sky Gym, owned by former wrestler and IWE referee Takao Kaneko. When he joined in May 1977, he was the promotion’s first new recruit in five years. Debuting in September 1977, Takasugi would become associated with subsequent trainees Hiromichi Fuyuki and Nobuyoshi Sugawara as the “three crows” of late-period IWE. As the IWE began its death spiral in 1980, an opportunity emerged for Takasugi. That November, Carlos Plata worked on the promotion’s last tour of the year, and he recognized Takasugi’s skill and potential. Plata wanted to bring him to EMLL, and when he was booked again by the IWE the following spring, Carlos brought the documentation that would make Takasugi eligible for a work visa. This would not materialize during the IWE’s life due to the priority of funding Ashura Hara’s second excursion, which was intended to transition Hara to the heavyweight division. However, Takasugi would get his chance after the promotion’s final show in August. He traveled to the Mexican embassy in Tokyo to get his visa and embarked for Mexico with Mach Hayato. Although the promotion was so financially depleted that the wrestlers could not afford to pay their full trip back from Hokkaido to Tokyo, relying on the generosity of a bus driver to give them a free ride on the Tohoku Expressway, Takasugi got a final bit of support when IWE president Isao Yoshiwara covered his travel expenses in lieu of paying him for his final dates. Left: Takasugi as Ultraseven. Takasugi’s expedition was a success, and he developed friendships with fellow travelers from rival promotions, such as AJPW’s Atsushi Onita and NJPW’s Kuniaki Kobayashi, Hiro Saito, and George Takano. He temporarily returned to Japan at the start of 1982. While his peers Fuyuki and Sugawara had joined All Japan under the wing of Mighty Inoue, Takasugi was brought into the fold through former IWE sales manager Takehiko Nemoto, who had joined AJPW’s sales department. Takasugi had left his gear and belongings in Mexico, though, so he didn’t stay long. Takasugi pitched a masked gimmick to Giant Baba, inspired by the Tiger Mask boom as well as the success of Ultraman on NJPW house shows in the summer of 1979. This was apparently something that Hiro Saito had suggested to him, and Kuniaki Kobayashi had suggested a gimmick based on early-70s tokusatsu series Kaiketsu Lion-Maru. What Takasugi would get was Ultraseven, who had been the second superhero in the Ultra franchise. He struggled to make the mask from memory in Mexico, and called his younger brother, but it was difficult for his brother to find official resources due to the Ultra franchise’s decline after Ultraman 80. He finally found a book, though, and Takasugi managed to complete the mask. While AJPW president Mitsuo Matsune apparently did gain permission from Tsuburaya Productions, the studio has never publicly acknowledged this, and states in official books that the only Ultra-derived wrestling gimmick that they have approved is Atsushi Onai’s Ultraman Robin. (According to a 2017 G Spirits book, there were plans circa 1984 to retool Takasugi with a gimmick based on Kinnikuman. NJPW's Junji Hirata was also bidding for the gimmick around that time, but neither would get it.) Takasugi appeared with an Ultraseven decoy in a June 1982 press conference, wherein a challenge was made to Atsushi Onita. He debuted for the company during the Summer Action Series tour and got his title match on July 9. While Ultraseven would appear again during that autumn’s Super Power Series, he would not join AJPW fulltime until 1983. That year, after Onita’s knee injury, he was among those who unsuccessfully challenged Chavo Guerrero for the NWA International Junior Heavyweight title, and he worked all but the last tour of 1984 as well, before accompanying Fuyuki on a UWA excursion. Takasugi wrestled as himself upon his return to All Japan in spring 1985, as the revived Kokusai Ketsumeigun heel faction gave someone with his roots a spot. However, Takasugi was ultimately a victim of budget cuts in spring 1986, cut alongside Sugawara, Ryuma Go, and referee Mr. Hayashi. Right: Takasugi (right) on the cover of the program for Pioneer Senshi's first show. Takasugi spent the next three years working freelance, sometimes as a mysterious masked wrestler on All Japan shows, or on events near his hometown. Alongside Go, he worked a full tour in summer 1987, likely to fill the holes left by the last couple of Japan Pro Wrestling talent to return to NJPW. In 1989, Takasugi, Go, and Sugawara reconvened to fire the first shot in the indie boom. Takasugi and Sugawara wanted to name the new promotion Shin Kokusai Puroresu (New International Pro Wrestling) but Go was hesitant due to his shame over having left the IWE in 1978. They settled on the IWE-reminiscent Pioneer Senshi, which they got from former IWE reporter and color commentator Takashi Kikuchi. Like Sugawara, Takasugi would only work the promotion’s first show in April 1989. While Sugawara got hooked up with a job coaching Koji Kitao and then working for SWS, Takasugi returned to freelance work in the early 90s. These included a match with Jushin Thunder Liger in 1990, where Takasugi took a page from Satoru Sayama’s book and billed himself as Super Seven. In 1993, he joined a union of independent promotions, upon which he would form his own IWA Shonan. Takasugi took bookings for various promotions, such as W*ING, the Takano brothers’ Pro Wrestling Crusaders, Takashi Ishikawa’s Tokyo Pro, and Go’s Oriental Pro. Meanwhile, IWA Shonan promoted shows in both Takasugi’s hometown and in Yokohama, which was the home of fellow Union promotion Kokusai Pro Wrestling Promotion, headed by Takasugi’s IWE senior Goro Tsurumi. Upon the Union’s dissolution in 1996, he renamed his company Shonan Puroresu. With the exception of a 20th anniversary show in 2016, however, Shonan has essentially been defunct since 1998, as Takasugi has concentrated on taking freelance bookings and running his own gym. Over the years, Takasugi has revived the Ultraseven gimmick on the indie circuit on occasion, while also working under his own name. In 2012, Takasugi made puroresu history when he teamed alongside his eldest son Yuki in a tag match, which was billed as a memorial for his old friend Go. Japan’s first father-son duo lost to Go disciple Kazuhiko Matsuzaki when Matsuzaki hit a neckbreaker drop on Yuki.

-

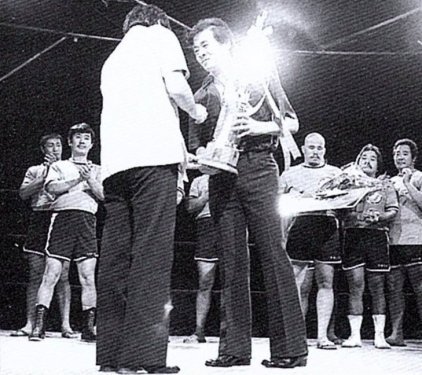

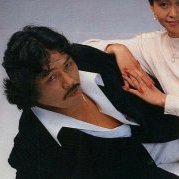

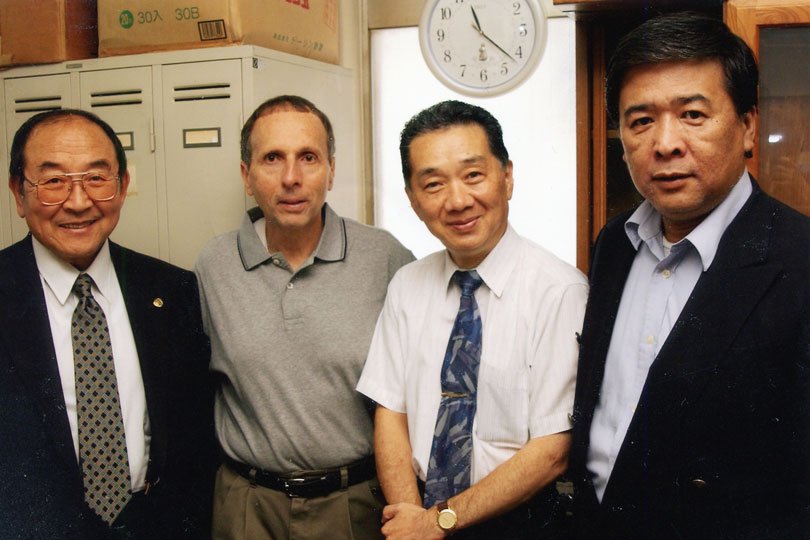

Kosuke Takeuchi (竹内宏介) Profession: Journalist, Editor, Commentator (Color) Real name: Kosuke Takeuchi Professional name: not applicable Life: 1/6/1947-5/3/2012 Born: Atami, Shizuoka, Japan Career: 1965-2006 Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise, All Japan Pro Wrestling (as commentator) Kosuke Takeuchi might have never worked between the ropes, but no chronicle of the history of puroresu is complete without him. The face of Gong magazine and a guru for generations of hardcore fans, Takeuchi was a pillar of puro culture throughout his forty-year career. [For a more detailed overview of the story of Takeuchi and Gong, see my blog post “Kosuke Takeuchi, Gong Magazine, and Various Maniax”, published on the tenth anniversary of his death.] While born in Atami, Shizuoka, Kosuke Takeuchi grew up in Tokyo's Taito ward. At the age of 8, he was hooked for life by JWA broadcasts on street televisions, and found his way to a job at Professional Wrestling & Boxing magazine in his senior year of high school. Takeuchi was frustrated by the magazine’s dry presentation—which was essentially an extension of the Daily Sports evening paper—and attempted to quit in 1966. He was promoted to the editorial department instead, and when the man who had gotten him that job and promotion, Yukio Koyonagi, left their parent company, Takeuchi was scouted for a new magazine. Left: Takeuchi goes on the mat with the man he made a star in Japan. Gong and Monthly Gong published content analogous to the Stanley Weston magazines of the West (that is, the “Apter mags”). It first hit shelves in 1968, and over the next decade, it would help make Takeuchi one of the most influential men in puroresu. Gong’s extensive coverage of Mil Mascaras, which began three years before he ever worked in Japan (and likely led to that even happening), was the most famous example of this. Takeuchi was also an important ally of NJPW, as Gong's coverage of the promotion balanced out the more pro-Baba Monthly Pro. In the mid-to-late 1970s, a generation of superfans began to rally around Takeuchi, competing amongst themselves through their myriad fan clubs to win his favor. Simply put, his impact was massive. Through his fan club connections, Takeuchi could be relied on to help make the magic happen for an important match. AJPW’s famous “Idol Showdown” of 1977, in which Jumbo Tsuruta defended his NWA United National title against Mil Mascaras, was supported by cheer squads which Takeuchi himself arranged on opposite ends of the arena (you can see them in cutaways during the match). Tatsumi Fujinami's first match against Ryuma Go was essentially carried in the same way, as members of unrelated fan club manufactured crowd support for the latter. While this was long unacknowledged in the West, Takeuchi is probably the primary source of unofficial footage of 1970s puroresu, whether that was through 8mm clips he had acquired (and had encouraged his biggest fans to shoot themselves) or the many home video recordings he had made of television broadcasts. These are just a couple of his many contributions to puroresu, though. Later on, he would be credited with giving Giant Baba the idea to license Tiger Mask for AJPW, as well as conceiving the name of FMW. Takeuchi began work as a commentator for AJPW and the IWE in the late 1970s, originally serving as a special guest for Mascaras’ matches in 1978. Over time, as Takeuchi scaled his Gong role back to an editorial advisor, he became more prominent in this role. However, Takeuchi’s regular commentary duties ended in 1992. He would continue to be a prominent figure in the wrestling journalism sphere for over a decade afterwards, and even returned to the magazine he had built during its darkest hour in the 2000s. Takeuchi suffered a massive stroke during a morning commute in 2006 and was left incapacitated until his death in 2012. Takeuchi (second from right) with Hisashi Shinma, George Napolitano, and Joji Inoue in 2004.

-

Tadaharu Tanaka (田中忠治) Profession: Wrestler, Trainer Real name: Masakatsu Tanaka (田中政克) Professional names: Masakatsu Tanaka, Tadaharu Tanaka Life: 1/26/1942- (presumed alive) Born: Hofu, Yamaguchi, Japan Career: 1958-1977 Height/Weight: 176cm/105kg (5’9”/231 lbs.) Signature moves: Sunset flip Promotions: Japan Pro Wrestling/JWA, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: IWA World Mid-Heavyweight [IWE] (1x) Tadaharu Tanaka was one of the JWA’s first proper trainees, most notable for his close association with Toyonobori and for establishing the IWE’s “middleweight” division at the end of the sixties. Masakatsu Tanaka joined the JWA after graduating from junior high in 1957. As the promotion had been staffed in its early years by experienced athletes in sumo and judo (or amateur wrestling, in one case) who transferred to pro wrestling, Tanaka was among its earliest trainees in the proper sense, alongside high school baseball star Yasuhiro Kojima (the future Hiro Matsuda). He would become Toyonobori’s valet and his closest confidant. At one point in the early sixties, Tanaka was ordered to switch to boxing, as Rikidozan was intent on training a champion in the sport through his gym. The ring name Tadaharu Tanaka, which seems to have originated in 1964, was one of Toyonobori’s many inventions. An uncited passage on Tanaka’s Japanese Wikipedia page claims that Tadaharu was taken from Chuji Kunisada, a 19th century gambler who has long been romanticized as a chivalric figure. 忠治 can indeed be read as both Tadaharu and Chuji, and the reference would be in line with Toyonobori’s love for nicking names from the stock characters of Edo-period historical dramas. Tanaka was the leader of Toyonobori’s posse, the Hayabusa-tai (“Falcon Corps”). Presumably named after the 64th Squadron of the Imperial Japanese Army, which had been led by the well-propagandized aviator Tateo Kato, the Hayabusa-tai’s best-known incident revolved around a Ventures concert that they were intended to promote (for those unaware, the Ventures were *huge* in Japan)…until Kokichi Endo swiped the rights and got all the money, albeit with a beating. I bring it up because the Hayabusa-tai made up a good portion of the dream team that Toyonobori had in mind when he began to put Tokyo Pro Wrestling together. Sure enough, Tanaka was among those who jumped ship to join his senior. According to the Japanese zine Showa Puroresu, Tanaka did not temper Toyonobori’s penchant for spending money he wasn’t supposed to spend, but in fact inherited it. During Antonio Inoki’s legal disputes with Toyonobori and Hisashi Shinma in 1967, it was reportedly disclosed that Tanaka had personally misappropriated funds which had been allocated for Tokyo Pro’s training camps. Their recruits were thus forced to receive their first training on a beach in Ito instead of a ring, and as Haruka Eigen later recalled, the company had been unable to afford rice to feed them. In December 1966, when Inoki created the Tokyo Pro Wrestling Ltd. company to split the rest of the roster from Toyonobori, Tanaka was the only other wrestler who was excluded. Due to this, Tanaka did not participate in the Tokyo Pro-IWE joint tour of January 1967, but he joined the IWE alongside Toyonobori in time for their second tour that summer. It was in his early years with Kokusai that Tanaka’s career peaked. In early 1969, he worked a program with British wrestler Mike Marino, winning Marino’s newly minted IWA World Mid-Heavyweight title that February. It is a pervasive belief among IWE fans that Toyonobori had lobbied for Tanaka’s push, although then-valet Mighty Inoue stated that he didn’t think that was the case in a 2016 interview with Showa Puroresu. Whatever the case, this made Tanaka puroresu’s first junior heavyweight champion since IWE president Isao Yoshiwara himself in the early 60s, and while footage of Tanaka does not survive, it is apparent that he presaged the IWE’s later talent in this vein, such as Inoue and Isamu Teranishi. He would remain with the company even as Toyonobori retired in 1970, only losing his title when he vacated it in March 1971 to embark on his excursion. Like other Kokusai wrestlers of the period, Tanaka’s overseas training saw him compete in France, Spain, Germany, and even South Africa, before his return the following June. For whatever fanfare his homecoming might have received, Tanaka did not break through upon return, but recede. It appears that he was overshadowed by wrestlers like the aforementioned Teranishi and Inoue, and he began to work more as a trainer. He reportedly began to experience liver problems in the mid-70s, and announced his departure in September 1977, without working a retirement match. In a 2009 blog post, Great Kojika claimed that he had met Tanaka during an All Japan show in Tanaka’s hometown. While it has been presumed that he is still alive, Tanaka did not come forth when the Rikidozan OB Kai alumni association was formed in 1996, and Kojika’s alleged encounter is the last anyone has heard from him.

-

- iwe

- tokyo pro (1966-67)

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

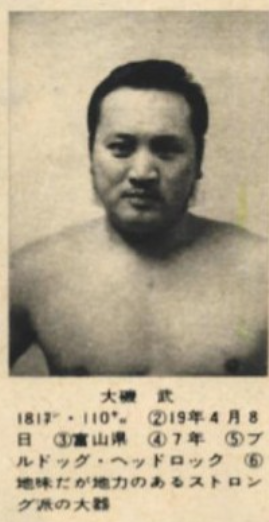

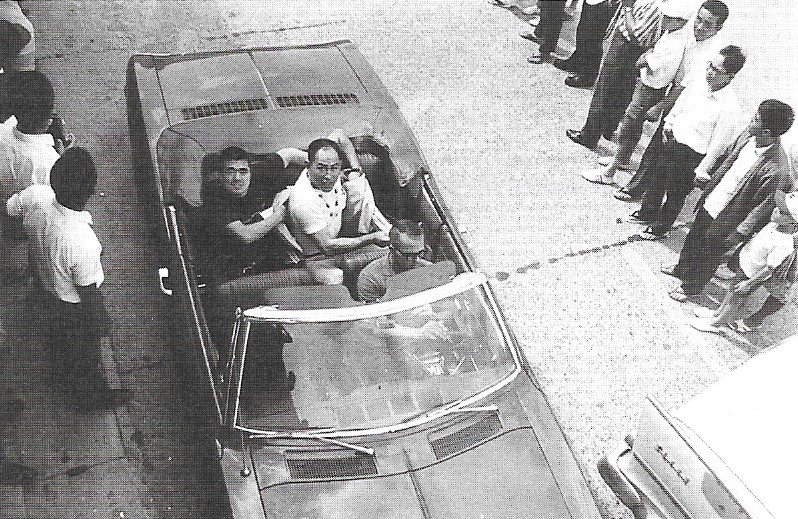

Takeshi Ōiso (大磯武) Profession: Wrestler, Promoter, Trainer Real name: Takeji Suruzaki (摺崎武二) Professional names: Takeshi Ōiso, Takashi Surazaki Life: 4/8/1944- Born: Shinimato, Toyama, Japan Career: 1966-1974 (in Japan; range of years during Filipino phase unknown) Height/Weight: 181cm/117kg (5’11”/257 lbs.) Signature moves: Headbutt Promotions: Tokyo Pro Wrestling, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Takeshi Ōiso was a sumo-to-puroresu transplant who wrestled for eight years, joining Tokyo Pro Wrestling and then being subsumed into the IWE. However, he is most notable for his second life as a pioneering promoter of Filipino pro wrestling. Takeji Suruzaki joined the Tachinami sumo stable in 1963, debuting in the July tournament under his real name. He would receive the shikona Ōisonami upon entering the makushita division in March 1965 but decided to retire after the May 1966 tournament. Suruzaki had submitted an application to the JWA after Rikidozan’s death, but the promotion had not been seeking new recruits and turned him down. This time, it would be Toyonobori who came to him, as the deposed president and ace was building a roster for his new enterprise, Tokyo Pro Wrestling. Suruzaki was one of the ex-sumo talent recruited for the promotion, alongside Tetsunosuke Daigo, Haruka Eigen, Katsuhisa Shibata, and Isamu Teranishi. (A sixth, Hiroshi Nakagawa, was among them, but would leave the business after Tokyo Pro's only tour.) Suruzaki immediately took a ring name which blended his real name (albeit tweaked) and shikona, Takeshi Ōiso. After Tokyo Pro’s disastrous first shows in 1966, and their one joint tour with the International Wrestling Enterprise in January 1967, Ōiso was subsumed into the latter organization like most of the Tokyo Pro roster. Ōiso's IWE career was generally unremarkable, and he reportedly considered retirement until Jose Arroyo booked him for a Spanish tour in 1972. Ōiso spent the next year touring Europe and Africa before returning home for the 5th IWA World Series tournament in autumn 1973. Despite his expedition, Ōiso decided to leave the business shortly after his return, wrestling a retirement match on January 29, 1974. Left: An NJPW-APW joint show in February 1984. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling #31 (March 6, 1984) - picture included in free preview pages of digital copy] None of this, though, is what is most interesting about Ōiso. As the story goes, one of Toyonobori’s obsessions was the Yamashita treasure, a mythical stash of Imperial war loot from their Southeast Asian campaigns named after general Tomoyuki Yamashita. While this treasure is now mostly considered to have been an urban legend (notwithstanding the absolutely buckwild legal drama between Filipino treasure hunter Rogelio Roxas and Ferdinand Marcos - yes, *that* Ferdinand Marcos - which began in the late 80s), Toyonobori was a believer who had approached several wrestlers about hunting for it. At some point, Ōiso took him up on that offer, and though it was clearly unsuccessful, the experience must have stuck with Ōiso. After his retirement, he decided to move to the Philippines to work as a trader, but he would bring professional wrestling along with him. At some point, Ōiso formed a promotion called Asian Pro Wrestling, for which he served as promoter and trainer. In February 1984, he returned to the ring for APW’s most notable shows: a pair of joint dates with New Japan Pro-Wrestling in Quezon City. These saw him team with disciples Harris Montero and Mario Matulac in matches against, respectively, Killer Khan & Animal Hamaguchi, and Yoshiaki Fujiwara & Osamu Kido, and APW won in both cases. APW folded sometime after this, but Ōiso protege Conrad Encinas eventually formed Reverse Pro Wrestling, which stated itself as APW’s successor. RPW has since moved its operations to France and become World Underground Wrestling, but continues to have a division in the Philippines.

-

Azumafuji (東富士) Real name: Kinichi Inoue (井上謹一) Professional names: Azumafuji Life: 10/28/1921-7/31/1973 Born: Shimoya-ku (present-day Taito), Tokyo, Japan Career: 1955-1958 Height/Weight: 179cm/125kg (5’10”/275lbs.) Signature moves: Saba ori (sumo bearhug) Promotions: Japan Pro Wrestling/JWA Titles: NWA Hawaii Tag Team [Mid-Pacific Promotions] (1x, w/Rikidozan) The first yokozuna to enter puroresu, Azumafuji spent about four years with the JWA. While ostensibly pushed as a top native talent, he ultimately realized that the company wasn’t big enough for two major ex-sumo stars. Kinichi Inoue was a big kid, weighing 6.8kg (15 lbs) at birth and over 75kg (165 lbs.) by the time he was twelve. He gained a local reputation for his strength through the judo he had been taught in elementary school and his help at the family ironworks. This eventually reached the ears of Fujigane IV, who got Kinichi to agree to join his new Takasago stable after graduating elementary. At that point, Kinichi’s 165cm height was below the required minimum, but Fujigane cut a deal with an examiner to let him in anyway. Sumo did not come naturally to Kinichi, and in an era where only two tournaments were held per year, it took him two years to pass the lowest division of maezumo. Fujigane held firm, vociferously defending Inoue to his stablemates and moving the young rikishi to work hard. Once he got through maezumo, Kinichi rose through the ranks, receiving the shikona Azumafuji upon reaching the sandanme division in 1939. Azumafuji wins his final tournament by defeating Tochinisiki on October 29, 1953. Just before Azumafuji was promoted to juryo, he had a fateful encounter with Futabayama during a tour of Japan-occupied Korea. Breaking rank to challenge the yokozuna after Futabayama had plowed through all the sekitori in multiple exhibitions, Azumafuji was chided for his impudence and did not do any better than his superiors. However, he had endeared himself to Futabayama, who from that day forward invited Azumafuji to his training sessions. Azumafuji’s career would continue to be difficult, as a combination of injuries and temperament likely kept him from ever matching such a dominant yokozuna as Futabayama. Nevertheless, Azumafuji himself would reach the sport’s highest rank in 1949. In fact, Azumafuji was the final yokozuna to be promoted by the House of Yoshida Tsukasa. In 1950, the absence of all three yokozuna from the first tournament of the year, combined with the forced retirement of Maedayama (who had been photographed at a baseball game after dropping out of a tournament claiming illness), led the Japan Sumo Association to decide that the Yoshida family would relinquish the right to promote yokozuna, in favor of a special committee of sumo experts. Azumafuji continued to compete until he suddenly announced his retirement in 1954; he did not wish to hinder the promotion of Tochinisiki, who otherwise would have been the fifth active yokozuna. When a horrified Tochinisiki met him personally to beg him to reconsider, it actually did the opposite, convincing Azumafuji that he deserved to become a yokozuna immediately. After his retirement, Azumafuji was introduced to Rikidozan by Rikidozan’s patron, Shinzaku Nitta. (The 2019 Crowbar Press book Japan: The Rikidozan Years claims that Nitta had also been a patron of Azumafuji, but I want to see a Japanese source that corroborates this information before I parrot that.) Azumafuji and Rikidozan had been friends in the sumo days, and during his sumo career, Azumafuji had even borrowed a convertible from him for his Tokyo parade after winning his first championship. (Yusho winners have paraded in open-top cars ever since.) Convinced to transfer to professional wrestling, Azumafuji traveled to Hawaii with Rikidozan that spring to begin training under Oki Shikina. While he had competed at a peak weight of nearly 400 pounds during his sumo career, Azumafuji would wrestle at around 275. Azumafuji and Rikidozan won the territory’s tag titles from Bobby Bruns & Lucky Simunovich during their expedition, with Azumafuji still wearing his topknot. It would not be cut until July 7, eight days before Azumafuji was set to make his domestic debut. This cartoon describes Azumafuji’s first JWA match better than any photograph likely could. [Source: Puroresu magazine, August 1955] In his 2000 book Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945-1970, Yoshikuni Igarashi wrote what is still one of the only pieces in the English language to seriously analyze Rikidozan (and by extension puroresu) as a cultural phenomenon. I’m going to turn over to him on that match: “Indeed, one of the most memorable moments for Rikidozan fans was a match between Azumafuji and the Mexican wrestler Jess Ortega in 1955. Azumafuji did not put up much resistance and was beaten unconscious. However, despite the fact that it was a singles match, Rikidozan jumped into the ring and applied his karate chops to Ortega, who then fell out of the ring. The scene was a bit too perfect, probably prearranged by Rikidozan and Ortega, but the crowd simply loved it. Azumafuji, moreover, damaged his own image in another match when he attempted to stop a fight between Rikidozan and Ortega. Azumafuji’s tagmate, Rikidozan had slammed Ortega’s head twice into a corner steel pole; Ortega’s head was covered with blood, and his wound later required some twenty stitches. Making a feeble attempt to stop the ringside fight, Azumafuji caught his thumb between Ortega’s head and the steel pole and broke it. The former sumo champion never matched Rikidozan in the presentation of this new form of entertainment, and the authority of sumo plummeted along with the formidable reputation of Azumafuji.” In October 1956, the JWA held an interpromotional tour with wrestlers from the regional promotions Yamaguchi Dojo, Asia Pro-Wrestling, and Toa Pro Wrestling, split between three tournaments in the light, junior, and heavyweight divisions. This tour was intended to delegitimize the JWA’s competitors and/or scout whatever talent was worth swiping from them, but it was also intended to build up Azumafuji. In the heavyweight division, Azumafuji reached the finals to face Toshio Yamaguchi, who in January 1955 had wrestled Rikidozan for puroresu’s first title. After their first match ended in a draw, a rematch saw Azumafuji win. This gave Azumafuji the right to challenge Rikidozan for that belt, but whether it was due to the tailspin that Nitta’s death, poor attendance, and the fallout with Sadao Nagata sent the JWA into, or solely down to Rikidozan’s ego, that match never happened. Azumafuji was reportedly generous during his JWA tenure, lending money to fellow wrestlers even though he wasn’t paid much better than them. In the second half of 1958, he led the locker room in their attempts to press Rikidozan for better wages. However, in what accomplice Surugaumi would later call betrayal, Azumafuji decided to retire after getting nothing but some money and smooth talk from Rikidozan. The papers printed the cover story that he had suffered a hairline fracture in his elbow after slipping in his bathroom. In 1959, Azumafuji took a sumo commentary job with Fuji Television, which he would hold until 1966. In addition to writing a sumo column for Nikkan Sports until 1971, he ran a successful consumer loan firm and managed a restaurant (albeit to less success). He died of colon cancer in 1973. [Credit goes to a two-part profile (part 1, part 2) in the defunct Sumo Fan Magazine, written by Joe Kuroda, for virtually all of the information here that doesn’t pertain to puroresu.]

-

Joe Higuchi (ジョー樋口) Profession: Wrestler, Referee Real name: Kanji Higuchi (樋口寛治) Professional names: Kanji Higuchi, Joe Higuchi Life: 1/18/1929-11/8/2010 Born: Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan Career: 1954-1997 Height/Weight: 178cm/100kg (5’10”/220 lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association, Japan Wrestling Association, All Japan Pro Wrestling, Pro Wrestling NOAH Titles: none Joe Higuchi was one of puroresu’s greatest referees and a beacon of hospitality for foreign talent. An athletic child, Kanji Higuchi claimed that he was encouraged to pick up judo by the leader of a kendo club, after Kanji lost his temper during a kendo match and tossed his shinai aside to grapple his opponent and take their mask. Higuchi stuck with judo through junior high, but after the war broke out, he was mobilized for factory work and could not concentrate on it. Higuchi also states that he very nearly died during a bombing raid as his factory was targeted; fortunately, Higuchi had skipped work that day to listen to a jazz record his friend owned. Higuchi entered university in April 1945, but with his country’s surrender that August, martial arts clubs would be banned in the early days of the occupation. This did not mean that judo itself was outlawed, though, and after Higuchi won a prefectural competition, a Japanese-American soldier named George Hamaguchi offered Kanji a job teaching judo to American servicemen. Higuchi initially refused, but Hamaguchi was insistent, and Kanji would be convinced when he saw the quality of the facility. It was during this time that Higuchi learned English, and his connection to the US military kept him well-fed despite scarce supplies. When his frequent visits to the military gymnasium resulted in his expulsion from university, Hamaguchi got him employed. It was while working with the military that Higuchi attended one of the Torii Oasis Shriners Club shows of 1951. Headed by William F. Marquat, the last of Douglas MacArthur’s Bataan Boys to remain stationed in Japan after Truman relieved MacArthur of his command, the club had arranged a deal with Hawaii wrestling promoter Al Karasick to run a series of professional wrestling shows to entertain the troops and raise funds for a charity drive to help children who had been crippled by the war. This tour is most famous for having featured Rikidozan's professional wrestling debut. My source states that Higuchi saw one of the shows which also featured exhibition fights with the soon-to-retire Joe Louis, which would make it one of five shows between October 18 and December 11. (Assuming he was stationed in Osaka, it would have been the November 25 show at the Osaka Stadium.) Higuchi and Yuichi Deguchi in an Osaka parade, during their time in the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. [Photo credit: G Spirits Vol. 62] After the occupation officially ended in 1952, Higuchi remained employed by the US military. However, he decided to leave his job despite familial objections to apprentice under Toshio Yamaguchi, who formed the regional All Japan Pro Wrestling Association in Osaka. While no AJPWA records exist for this timeframe, Higuchi later stated that he debuted at a Matsuzaka show in May 1955. Due to his bilinguality, and the promotion’s reliance on hiring locally stationed or living American servicemen as opponents, Higuchi was working as a referee even this early. (One photograph of the AJPWA roster shows Higuchi sitting in referee attire on the far right.) In 1956, the Association officially disbanded when local Yakuza boss (of the Sarae-gumi gang) Shotaro Matsuyama withdrew his support for health reasons. Higuchi was one of the core members who remained with Yamaguchi, relocating to Toshio’s hometown of Mishima that summer to run shows in poverty as Yamaguchi Dojo. Higuchi later recalled that he had eaten three meals a day in Osaka, but during his Yamaguchi Dojo period, he was forced to subsist on udon noodles cooked with seawater broth in an aluminum basin. Higuchi was one of the participants in the Japan Championship League tournament, an October interpromotional tour organized by the JWA. This tour is generally considered to have been an effort for the JWA to delegitimize their regional competitors and scout talent worth poaching from them, and there were multiple shoot incidents, particularly in the first show (which was closed off to the public and media). Higuchi managed to place third in the light heavyweight bracket, and it has long been reported that in the second round, he got the better of bodybuilder turned JWA midcarder Takao Kaneko with a shoot arm lock. The following year, Higuchi was one of five regional wrestlers hired by the JWA; the others were fellow Yamaguchi Dojo men Michiaki Yoshimura, Yuichi Deguchi, and Hideyuki Nagasawa, and Asia Pro Wrestling’s Kiyotaka Otsubo. Unlike Yoshimura, who was briefly pushed as a top wrestler in the company on short-lived weekly television programs (these were an attempt to make up for the revenue lost by cutting ties with Sadao Nagata, the live entertainment don on whom they had wholly depended to book house shows), Higuchi was an undercarder and stayed there. However, when Rikidozan learned he was fluent in English, Higuchi began pulling double duty as a handler for foreign talent. He drew upon the culinary knowledge he had gathered during his work on military bases to provide American wrestlers with a taste of home when touring provincial markets, keeping them fed on steak, potatoes, soup, and salad. Higuchi’s cooking would gain enough of a reputation that he even cooked for Rikidozan. Despite his usefulness backstage, though, Higuchi decided to retire in 1960 due to his lack of progress between the ropes. He tried to run some sort of water business in Osaka, but it failed, and he returned to the JWA in a backstage capacity in 1963. Joe’s job was to look after foreign talent and keep them in condition to perform. Over the decades, some would not listen, and Joe was forced to earn their respect.1 Joe did not become a JWA referee until 1966. This happened because head ref Oki Shikina was arrested for illegal firearm possession, leaving Yusef Turk and Yonetaro Tanaka as the only ones in the position. Michiaki Yoshimura, now a top executive, remembered that Higuchi had experience in the role from their time in the AJPWA, so he ordered him to take the position. In an era where foreign heels in puroresu frequently assaulted officials, Joe focused exclusively on training his bumping skills. He became so good that Giant Baba remarked that he was better at ukemi than when he was a wrestler, and word of his performances quickly spread. In 1967, Higuchi was invited by several American promoters to work with them. Joe took them up on these offers, honing his skills and building relationships. As the BI-gun era of the JWA progressed, factions began to form behind Baba and Inoki. This extended to the referees, as Turk officiated Inoki’s matches while Oki officiated Baba’s. As the JWA entered the post-coup malaise of 1972, Higuchi eventually decided to leave the company, and Michiaki Yoshimura did not try to stop him (he himself was planning to retire soon). Higuchi had settled on working in the States, but when he asked JWA liaison officer Ryozo Yonezawa to procure a work visa, another opportunity arose. Unbeknownst to most, Yonezawa had decided to follow Baba in forming a new organization, and when he relayed this to Baba, Higuchi received an offer to join what would become AJPW. Higuchi had started a family by this time, so he was grateful to have a domestic job offer, but he had already been told by American promoters to “come immediately”. Joe apologized and shaved his head as a display of contrition, but when he explained the situation, they laughed and told him that it would be easier to work with Higuchi anyway if Baba had set up an office in Japan. Despite the amiable reaction, Joe would keep the skinhead look for the rest of his life. Higuchi officiates Jack Brisco's June 14, 1974 (the caption is incorrect) NWA title defense against Dory Funk Jr. in the Kiel Auditorium. In its early years, AJPW continued the JWA tradition of hiring American referees. Initially booked on a tour-by-tour basis, All Japan settled on JWA referee Jerry Murdock after the latter folded. Murdock remained with the company until he was fired in summer 1976, but Higuchi was treated as a head referee from the start. In 1974, Joe received perhaps the greatest honor of his career when he accompanied Baba to the United States. On June 14, Baba arrived in St. Louis to defend his PWF Heavyweight title against Dick Murdoch in the Kiel Auditorium. Unbeknownst to Higuchi, who had left his referee outfit in his hotel room, NWA president Sam Muchnick was intent on having Joe referee a NWA World Heavyweight title match between Jack Brisco & Dory Funk Jr. He rushed to his hotel and returned in the proper attire to officiate one of Brisco and Dory’s many 60-minute draws of the period in the venue synonymous with the NWA president. I believe some notes on Higuchi’s style are appropriate, considering trends I have seen in the evaluation of his work (such as a couple comments on his Cagematch profile), which chiefly focus on his work in the context of AJPW's popular 1990s period. Kyohei Wada recalled in his 2004 autobiography that it took time for him to appreciate Joe’s style. While Joe was clearly the most fleet-footed referee in Japan during his peak, Wada noted that he “barely moved” much of the time. Eventually, though, Wada realized that that was the point. In an era so influenced by the classical NWA style, in which much of wrestling was on the mat and so much more importance was placed on transitions than spots, Higuchi knew that in order to keep the crowd engaged, he had to be not independent of the wrestlers, but contrapuntal to them. When both wrestlers were standing, sure, he barely moved, but whenever one of them got a headlock takeover or arm lock, Joe hopped around better than anyone. Journalist Kagehiro Osano has recalled that Joe, like his successor, was the perfect referee for a ringside photographer, as he was careful never to examine a hold from the most obvious angle and obstruct the best shot. Finally, there is the matter of Joe’s count speed. It’s a reasonably legitimate three seconds, but such verisimilitude is dissonant with the rhythms of post-NWA wrestling. If one believes that it is fair to judge referees against each other across time like wrestlers, then I would at least suggest framing one's evaluation of Joe primarily in the context of the product of AJPW’s first phase, or at least not solely judging him on his twilight work. Higuchi remained AJPW’s head referee for a decade. In the main event of the Tokyo Sports show of August 31, 1979, in which BI-gun mounted a one-night reunion to face Abdullah the Butcher & Tiger Jeet Singh, Higuchi’s assignment as referee was explicitly approved by Inoki. His position only started to shift in the Japan Pro era of the mid-1980s, whose AJPW vs JPW matches would be officiated by Tiger Hattori, at Riki Choshu’s request. In the late 80s, Wada would be promoted to a co-lead referee spot to fulfill Hattori’s function of officiating native vs native matches. As the Tsuruta vs Tenryu feud gave way to the Chosedaigun-Tsurutagun and Four Pillars eras, Higuchi handed off those duties to Wada. By Joe’s own admission, he was incapable of adopting the theatrical, “dancing” count style that the clutch "2.9-count" kickouts of those matches necessitated. Perhaps as a result, AJPW’s native vs foreigner matches were slow to adopt the modern nearfall. (Consider a match like Kenta Kobashi vs. Stan Hansen from September 4, 1991, which is laid out in a way that allows Kobashi to survive two Western Lariats without kicking out of either.) Besides, Joe’s hands were severely swollen from his long career, and even unable to use chopsticks. Higuchi in a press conference with Minoru Suzuki and Naomichi Marufuji. Higuchi decided to retire in 1997. He initially declined to receive a retirement ceremony, as he believed it was not a referee’s place to overshadow the wrestlers; in his late career, crowds had taken to chanting his name. Baba insisted, though, so Higuchi got a grand sendoff and officiated Mitsuharu Misawa’s March 1, 1997 Triple Crown defense against Steve Williams. Joe received a ceremony at the following Budokan show, on April 19. He remained with the company afterward as a foreign handler, leaving after the May 2, 1999 Tokyo Dome show. At Ryu Nakata’s insistence, though, Joe would join Pro Wrestling NOAH as an auditor. He became the chairman of their GHC committee and remained with the promotion for a decade. In December 2003, he returned to the ring to referee a Rikidozan memorial six-man tag, during which he broke up Kenta Kobashi's machine-gun chop spot in the corner: a humorous display of just how different wrestling had become since his heyday. Joe was hospitalized in September 2010 for lung cancer and died on November 8.

-

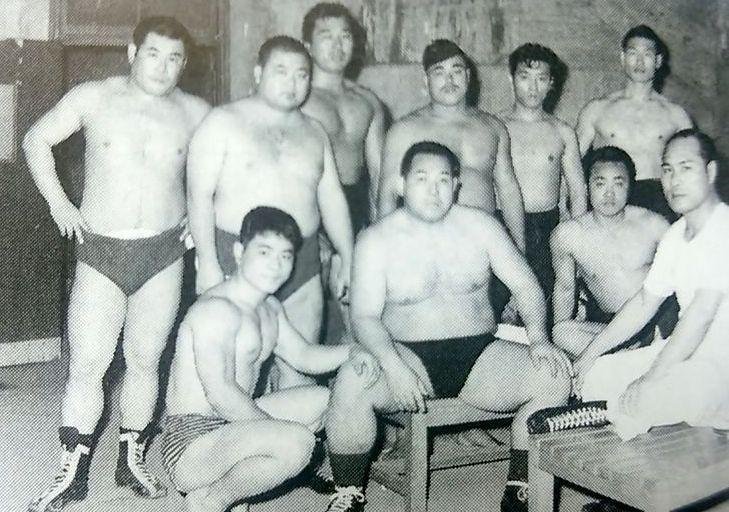

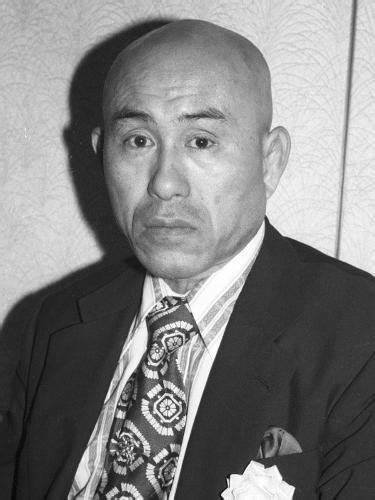

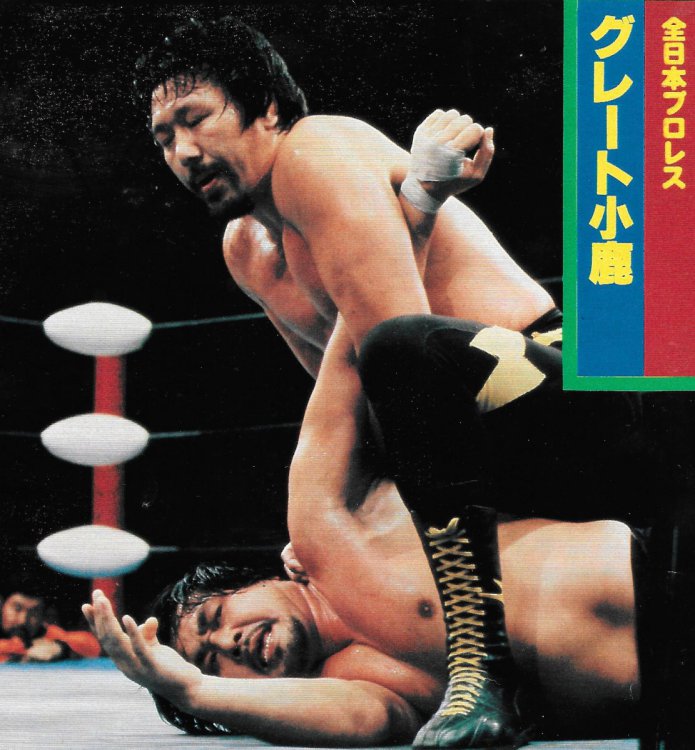

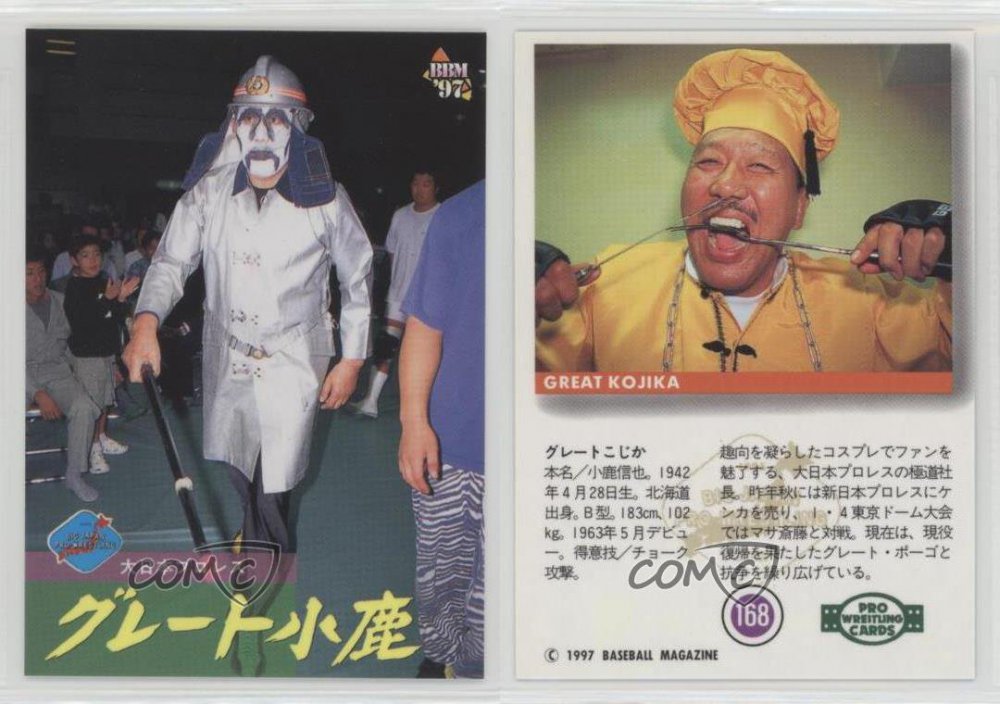

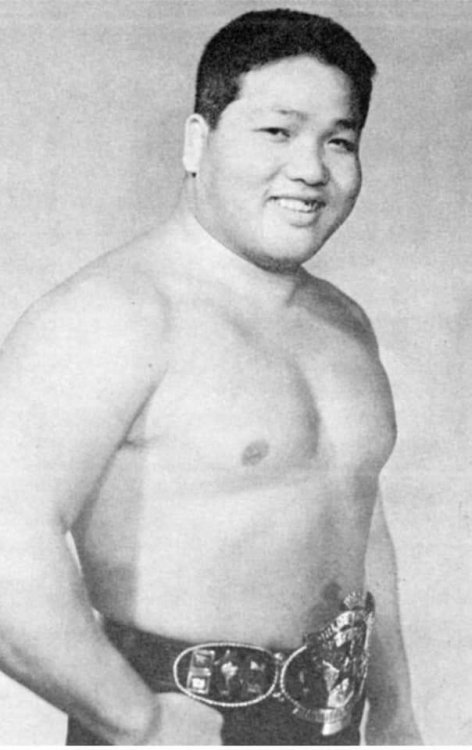

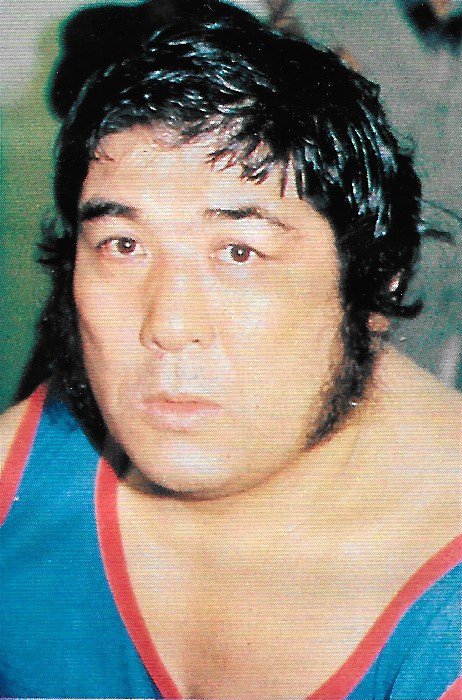

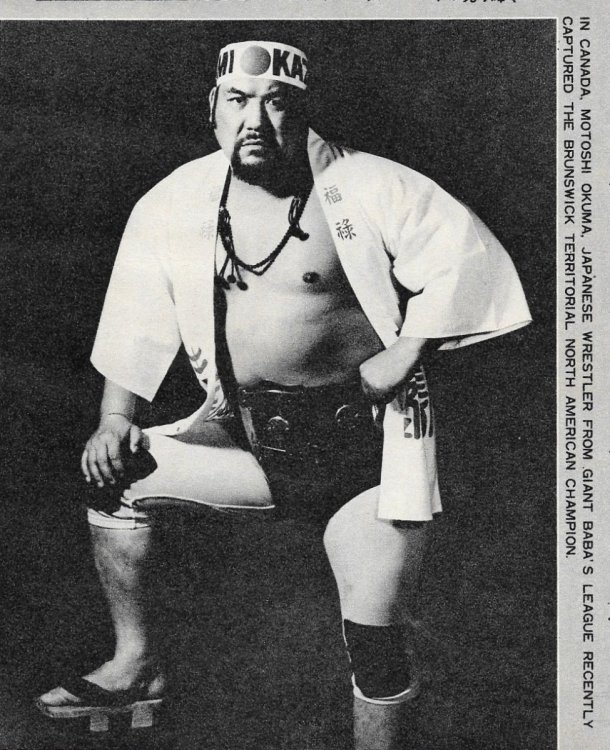

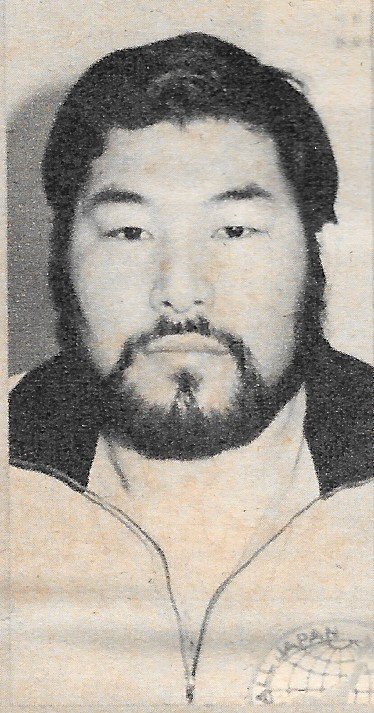

Great Kojika (グレート小鹿) Real name: Shinya Koshika (小鹿信也) Professional names: Shinja Koshika, Raizo Koshika, Great Kojika, Dory Boy, Kung Fu Lee, Masked GK Life: 4/28/1942- Born: Hakodate, Hokkaido, Japan Career: 1963-1986; 1995- Height/Weight: 185cm/115kg Signature moves: Knee drop, sleeper hold Promotions: Japan Pro Wrestling/JWA, All Japan Pro Wrestling, Big Japan Pro Wrestling Titles: NWA World Tag Team [CWA] (1x, w/Motoshi Okuma); NWA Beat the Champ Television Title [NWA Los Angeles] (2x); NWA Americas Heavyweight [NWA Los Angeles] (1x); NWA Americas Tag Team [2x, w/John Tolos]; All Asia Tag Team [JWA/AJPW] (4x; 1x w/Gantetsu Matsuoka, 4x w/Motoshi Okuma]; NWA Western States Heavyweight [Western States Sports] (1x); Sea of Japan Certified World 6-Man Tag Team [DDT] (1x, w/Riho & Mr. 6); UWA World 6-Man Tag Team Title [DDT] (1x, w/Riho & Mr. 6); Jiyūgaoka 6-Person Tag Team [DDT] (1x, w/Riho & Mr. 6); KING OF FREEDOM World Tag [Pro Wrestling FREEDOMS] (1x, w/The Winger); Yokohama Shopping Street 6-Man Tag Team [BJW] (1x, w/Kankuro Hoshino & Masato Inaba); Niigata Undisputed [Niigata Pro Wrestling] (1x); Niigata Tag Team [Niigata Pro Wrestling] (1x, w/Shima Shigeno) Great Kojika’s six-decade career brought him from one of the most decorated tag wrestlers in 1970s puroresu to an unlikely elder statesman of the Japanese indie scene. Shinya Koshika was forced to peddle to support his family from an early age after his father went blind. After graduating from junior high, he got a job at a canning factory, but left at 17 after unsuccessfully striking for better wages. As he tells it in a 2019 article, he was on a ferry to visit his uncle in Saitama when he had a chance encounter with Chiyonoyama. Koshika joined Chiyonoyama’s Dewanoumi stable, which at this point had bloated to 120 members and three stablemasters, and debuted in September 1959. He originally intended to stay for just two years but was convinced to wrestle for three so that he would be eligible for a ¥20000 (¥100000 in 2022) retirement package. After this, Koshika worked at a store until he became interested in joining the JWA, which he eventually did around November. Early in Koshika’s training, on February 4, 1963, an accident in a sparring session fractured Tokio Kido’s seventh cervical vertebrae and left him paralyzed for life; however, Kido reportedly did not blame Koshika for the incident and cited his own carelessness. Koshika’s earliest recorded match was on October 13, 1963, in which he lost to Kakutaro Koma. In 1964, he was rechristened Raijo Koshika for a time by Toyonobori. In his early career, Koshika served as the valet of Michiaki Yoshimura. Kojika during his time in Los Angeles. In 1967, shortly before he and Motoshi Okuma were sent on an American expedition, Koshika took a fan’s advice that “Kojika” was easier for a Japanese fan to chant than “Koshika” and changed his ring name. The two would work in the Tennessee and Georgia territories as the Rising Suns before Okuma left in 1968 due to homesickness. Kojika would remain abroad. He wrestled as a heel in the Florida, Detroit, and Los Angeles territories, and won multiple titles in the latter; in December 1969, he defeated Mil Mascaras in a cage match to win the territory’s top title for a month. Kojika has frequently recounted a night in May 1970 when he and Antonio Inoki went drinking in Los Angeles, and Inoki told him about his ambition to reform the JWA, over a year before the attempted coup. Kojika has also claimed that he was responsible for getting Abdullah the Butcher in touch with Mr. Moto to make his first Japanese appearances that same year. Kojika returned home for the JWA’s first NWA Tag Team League tour that autumn, teaming with Michiaki Yoshimura in the eponymous tournament. He would remain with the company for the rest of its life, and according to Dave Meltzer's Mr. Pogo obituary, he was running its dojo by the time that Sekigawa and the future Gran Hamada visited in 1971. While sympathizing with Inoki’s intentions and supporting a managerial reform, Kojika did not approve of the attempted coup d’etat that the reform proposal wound up just being pretense for. Early in New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s life, Kojika stormed their office with a katana to threaten Inoki. While Giant Baba asked him to make sure that those who wished to follow to start All Japan Pro Wrestling were not harassed, Akio Sato has claimed that Kojika sabotaged the fledgling promotion by going to Fritz von Erich to ensure his loyalty to the JWA, which would have forced Baba to align with Dory Funk Sr. [As a personal note, Fumi Saito expressed suspicion of this claim when I brought it up to him once, asking how Sato would know such a thing. Also, while Terry Funk's autobiography suffers from some errors when it comes to the Japanese side of things, he does not mention this as a factor in Baba's decision. I thought it was worth citing here but do treat it with a grain of salt until I can find more corroboration.] He would also order Kazuo Sakurada to shoot on Daigoro Oshiro on the last show before Oshiro left with Seiji Sakaguchi to join NJPW. In the promotion’s last days, Kojika won the All Asia Tag Team titles with Gantetsu Matsuoka, for what wouldn’t be the last time. As one of the nine wrestlers who remained with the JWA until the very end, Kojika signed a three-year contract with Nippon Television. Baba had been forced by the network and AJPW board of directors to acquire them (so that the failed NJPW-JWA merger would not have another chance to succeed) and regarded them as an impediment to his plans for All Japan. Kojika endeared himself to Baba both by rallying the talent and by voluntarily becoming his chauffeur. He and Okuma reunited for a handful of tag matches. However, he was soon “shocked” by Baba’s order for him to go on another excursion. Kojika arrived in Amarillo as Kung Fu Lee in September, which I suspect was done to fill Tomomi Tsuruta’s spot. (We know that Tsuruta’s training had been sped up from what was originally planned, in order to sell him as a prodigy worth pushing above the ex-JWA talent.) This run included a Western States Heavyweight title victory against Terry Funk in October, as well as multiple shots with various partners at the Funks’ NWA International Tag Team titles. Kojika returned to AJPW in autumn 1974. Upon Okuma’s return in 1975, the two reformed their tag team, now the Gokudō Combi. Kojika claimed in the 2000s that, in May 1975, he had secretly sought out Kintaro Oki to see if he was still under contract to NJPW, thus facilitating Oki's switch to an AJPW partnership. In March 1976, after former JWA president Junzo Yoshinosato announced that the All Asia singles and tag team titles would be revived with the NWA’s approval—an obvious attempt to delegitimize NJPW’s Asia League tournament—Gokudō accompanied Yoshinosato on a trip to Korea. As Oki and Kojika had been the last champions of their respective titles, both were given the right to challenge for the vacant belts again. On March 25 in Seoul, Kojika called on his experience as a heel to give Oki a worthy challenge for the singles title. The following day, also in Seoul, Gokudō defeated the young Korean duo of Oh Tae-kyun and Hong Mu-ung for the first of four All Asia tag reigns together. As his Nippon TV contract ended with the fiscal year on March 31, Kojika signed an AJPW contract. While this has never been confirmed (and likely never will be), journalist Kagehiro Osano noted in 2017 that Kojika was very likely responsible for booking All Japan undercard matches for several years, between the tenures of Masio Koma and Akio Sato. Kojika & Okuma’s first reign ended in October against Jerry & Ted Oates, who served as transitional champions towards Akihisa Takachiho & Samson Kutsuwada. Gokudō won the belts directly from the native team in June 1977, but would be forced to defend them in interpromotional matches against the IWE that fall. They handily defeated the team of Animal Hamaguchi & Goro Tsurumi on November 3, but when they entered enemy territory on the 6th, they lost to Hamaguchi & Mighty Inoue. The IWE held the titles until Gokudō won them back in the AJPW/IWE/Kim Il mini-tour of February 1978. This reign would end in vacation when the team failed to defend the belts, but in May 1979, they beat the Kiwis for their fourth, last, and longest reign. Kojika & Okuma held the titles for two years until a loss to Kevin & David von Erich. Kojika continued to wrestle for AJPW for five years. From what he says, the inciting incident behind his 1987 retirement came in July 1986. When the Summer Action Series I tour ended with an outdoor show in Kyoto, Kojika hurt his neck in a Gokudō tag against Mighty Inoue & Samson Fuyuki. While X-rays showed that Kojika had been nearly paralyzed by a piledriver, when Kojika told Baba the pain he was in, Baba allegedly responded coldly with “You can go home then.” If true it suggests that, as much of a chosen family atmosphere as All Japan may have developed, the ex-JWA talent who hadn't left alongside Baba never fully endeared themselves to him. Kojika officially retired with a 1987 ceremony and began working in his hometown as an event promoter, a side hustle he had already begun during his active career. A 1997 trading card of Kojika during his "Cosplay President" phase. The second phase of Kojika’s career began outside the ring, when Genichiro Tenryu tapped him to become a sales representative for WAR. This made Kojika responsible for booking venues. While I do not know if Kojika left because of this, his departure lines up chronologically with the internal backlash to Tenryu’s appointment of brother-in-law Masatomo Takei as company president, which led Takashi Ishikawa to break away. In December 1994, Kojika convened with Kendo Nagasaki (that is, fellow JWA remnant Kazuo Sakurada) and Eiji Tosaka, the president of the recently collapsed NOW, to form Big Japan Pro-Wrestling (Dai Nippon Puroresu) in Yokohama. Building a roster with the cooperation of Ishikawa’s Tokyo Pro Wrestling and IWA Japan, the organization held its first show on March 26, 1995. According to Kojika, Michiaki Yoshimura stepped in to help his former valet by making sure that Big Japan would not run into any trouble booking shows. Kojika initially stayed out of the ring, but due to sluggish attendance he started to wrestle again, beginning with an angle against Tarzan Goto. Kojika would garner the nickname “Cosplay President” for his penchant for wrestling in costumes (Iron Chef and Golga 13 being a couple). He would even appear in NJPW’s annual January 4 Tokyo Dome show in 1997, donning a tuxedo and tactical vest to wrestle Masa Saito. Kojika would step away from the ring as BJW developed, focusing largely on side ventures such as a chanko restaurant in Sendai, but BJW general manager Tosaka disliked these pursuits and obstructed them. As Kojika approached his seventies, he transferred BJW ownership to Tosaka and began to work dates across a variety of promotions, trading on the novelty of being Japan’s oldest wrestler. He has won a variety of indie titles in this period. Most of them are tag titles, naturally, but in August 2018 he won BJW’s own Niigata Openweight title to become the oldest Japanese wrestler to win a singles title.

-

Mr. Chin (ミスター珍) Real name: Yuichi Deguchi Professional names: Yuichi Deguchi, Mr. Chin, Mr. Yoto, Mr. Kamikaze Life: 10/12/1932-6/25/1995 Born: Takarazuka, Hyogo, Japan Career: 1954-1995 Height/Weight: 168cm/83kg (5’6”/183 lbs.) Signature moves: weapon attack Promotions: All Japan Pro Wrestling Association, Japan Wrestling Association, International Wrestling Enterprise, Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling Titles: NWA World Tag Team [CWF] (1x, w/Tojo Yamamoto) Mr. Chin had one of the most interesting careers in puroresu, a forty-year trajectory from puroresu’s first regional promotion to FMW. Yuichi Deguchi was a judoka working for the Hyogo prefecture’s riot police unit when he joined the International Judo Association in 1950. Often called “Pro Judo” for short, this was an entertainment organization formed by judoka Tatsukuma Ushijima [Wikipedia]. Ushijima had objected to Kodokan’s recent shift in strategy—promoting judo as an amateur sport, in an effort to have it approved for reintegration into the school curriculum—and wanted to build a new path for impoverished judoka to make a living as sports-entertainers. The Association was short-lived, but its provincial tours and promotional strategies have been cited as an influence on the puroresu industry that it preceded. A few years after the Association folded, Deguchi joined the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association. Headed by fellow Pro Judo alum Toshio Yamaguchi, the AJPWA was an Osaka-based regional promotion that had capitalized on the publicity surrounding the nascent Japan Pro Wrestling/JWA, running shows before the latter officially began tours and even beating it to the punch with puroresu’s first television broadcast. The Association could only afford to hire local American servicemen as foreign wrestlers, with the exception of P.Y. Chang. Deguchi teamed up with the future Tojo Yamamoto. According to puroresu journalist Etsuji Koizumi, the AJPWA officially folded when local Yakuza boss Shotaru Matsuyama withdrew from his duties as president and chief sponsor for health reasons. Deguchi was among those who remained with Yamaguchi, holding events in poverty as Yamaguchi Dojo in Toshio’s hometown of Mishima. Deguchi participated in the JWA’s interpromotional Japan Championship Series in October 1956; the following year, Deguchi was one of four Dojo wrestlers hired by the JWA, alongside Michiaki Yoshimura, Kanji Higuchi, and Hideyuki Nagasawa. In keeping with his character when working with Chang, and in a similar spirit to fellow JWA undercarder Yusuf Turk, Deguchi worked the gimmick of a heel named Mr. Chin. He came to the ring in Chinese clothes while sporting a headband with the Japanese flag, on which kamikaze (神風) was written. Chin walked on geta which he used as a weapon, and also weaponized mouthwash in an early antecedent of the poison mist tradition. Chin with Rusher Kimura in his IWE era. In 1961, Chin was seriously injured by an errant big boot from Giant Baba. He retired for two months but was encouraged to return to wrestling by a nurse whom he would marry. Upon his return, Chin bit Baba’s chest in a revenge match, leaving a scar that remained for the rest of his life. He would leave the JWA in 1964 after a stomach ulcer, and found work as an actor and television personality, but he returned to the business when he joined the IWE in 1970. Chin would go on an expedition to North America, working in Texas, Tennessee, Louisiana, and even Calgary. It was here that, as Mr. Kamikaze, he reunited with Tojo Yamamoto, and the two won tag gold in a couple territories. However, it was during this period that he developed diabetes. Returning to the IWE in 1976, Deguchi was booked as a foreign heel named Mr. Yoto, which I suspect was done to cut costs. He was inactive for a time, but when Goro Tsurumi and Katzuso Ooiyama formed the Independent Gurentai heel faction in 1980, Deguchi revived the Mr. Chin character to serve as their manager. He would also wrestle for the promotion in its last days. On the IWE’s final show, which took place in a school playground on August 9, 1981, Chin lost to Hiromichi Fuyuki by disqualification. After this, Chin worked abroad in the US, southeast Asia, and even the Middle East until the late 80s. However, this would not be the end of his story. In 1993, the 60-year old Chin debuted for FMW. Despite requiring frequent dialysis at this point, Chin would consistently wrestle in (frequently comedic) undercard matches for about a year. In his final match on July 31, 1994, Chin worked as the spoof gimmick Jinsei Chinzaki against frequent opponent Gosaku Goshogawara, working as Undertaker Gosaku. Chin died of chronic renal failure almost a year later, on June 26, 1995. Chin shakes the hand of Masato Tanaka on July 24, 1993, after putting the rookie over in his second-ever match.

-

Mitsu Hirai (ミツ・ヒライ) Real name: Mitsuaki Hirai (平井光明) Professional names: Mitsuaki Hirai, Shingo Hirai, Mitsu Hirai, Shintaro Fuji Life: 2/15/1943-10/28/2003 Born: Kobe, Hyogo, Japan Career: 1959-1978 Height/Weight: 179cm/104kg Signature moves: Sunset flip, dropkick Promotions: Japan Wrestling Assocation, All Japan Pro Wrestling Titles: NWA Mid-America Southern Tag Team [NWA Mid-America] (2x, w/Tojo Yamamoto) Summary: Mitsu Hirai worked for two decades as a midcarder and coach. Mitsuaki Hirai joined the JWA immediately after graduating from junior high. Debuting in 1959, Hirai wrestled under his real name while working as Rikidozan’s valet. In August 1963, Hirai began working as Shingo Hirai, and by this time, he had settled into a coaching role for young talent. He also booked their undercard matches. The Great Kabuki has spoken very highly of him in this regard, claiming that Hirai watched and critiqued their matches, and did not use corporal punishment. Hirai stands on the far right in a famous 1971 photograph of the JWA's top stars. In September 1964, Hirai left on an American expedition, where he would briefly hold tag gold with Tojo Yamamoto before returning twelve months later. He would work at least one South Korean tour for Kintaro Oki. In 1969, Hirai went on a Singaporean excursion, where he found some popularity as Shintaro Fuji. After his return, the perennial midcarder appeared in the only surviving match of his career, a March six-man with Inoki and Oki. That September, though, he would get the biggest opportunity of his Japanese career. When the JWA held the first NWA World Tag Team League, the first major annual tag team tournament in puroresu, it was decided that Antonio Inoki & Giant Baba would not work with each other due to Baba’s contractual exclusivity with Nippon Television. Hirai thus became Baba’s partner in the tournament. The Showa Puroresu fanzine recalls a claim that Hirai harbored a personal dislike towards Inoki and spearheaded the effort to have him expelled after the 1971 coup attempt. Hirai would remain with the JWA until its closure, signing a three-year contract with Nippon TV to work with AJPW. While he never took a head coaching position, comments made by Genichiro Tenryu in a G Spirits feature suggest that he may have still had some coaching input. As Akihisa Takachiho (that is, Kabuki) took over head coaching duties for a time after Masio Koma’s death, this would make sense. After his 1978 retirement, Hirai ran a coffee shop in Kobe, which had a corner dedicated to Rikidozan. He operated the store until the building was destroyed in the Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995 and died of heart failure eight years later. Hirai’s eldest son is former SWS/WAR/AJPW wrestler Nobukazu Hirai. Hirai's retirement ceremony was held at All Japan's August 27, 1978 show at Kobe Station Square.

-

Munenori Higo (肥後宗典) Real name: Atsushi Hongo (本郷篤) Professional names: Seikichi Hongo, Atsushi Hongo, Munenori Higo Life: 5/15/1945-7/23/2002 Born: Kumamoto, Kumamoto, Japan Career: 1969-1980 Height/Weight: 184cm/102kg Signature moves: Knee drop Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise, All Japan Pro Wrestling Titles: none Munenori Higo was an IWE product most notable for his 1972 transfer to the newly formed AJPW. A "baseball ace" at Kusari Nishi High School, Atsushi Hongo decided to join the International Wrestling Enterprise instead of going professional. He was reportedly inspired to do so by IWE star and Kumamoto native Great Kusatsu, for whom he would serve as a valet. Hongo was permanently transferred to All Japan Pro-Wrestling at its formation, alongside Thunder Sugiyama. It was at this point that he adopted the new ring name Munenori Higo. Giant Baba was apparently fond of him and had been his matchmaker. In 1974, Baba sent Higo on a three-month expedition to Australia. Despite this, Higo never managed to break out, and remained an undercarder for the rest of his career. In January 1979, Higo put over Bruiser Brody in his Japanese debut. The following April, Higo retired after a woman filed an assault charge. His former IWE coworker Mighty Inoue has claimed that it was a false accusation, but there have been no other comments on it to my knowledge. Higo worked as a promoter afterward, running AJPW shows in his hometown.

-

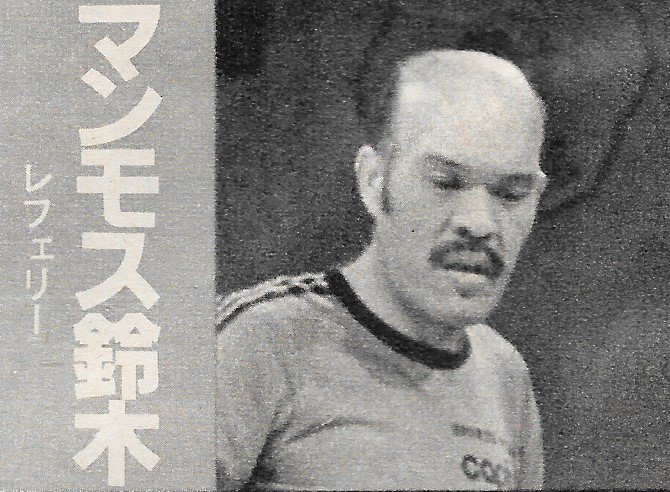

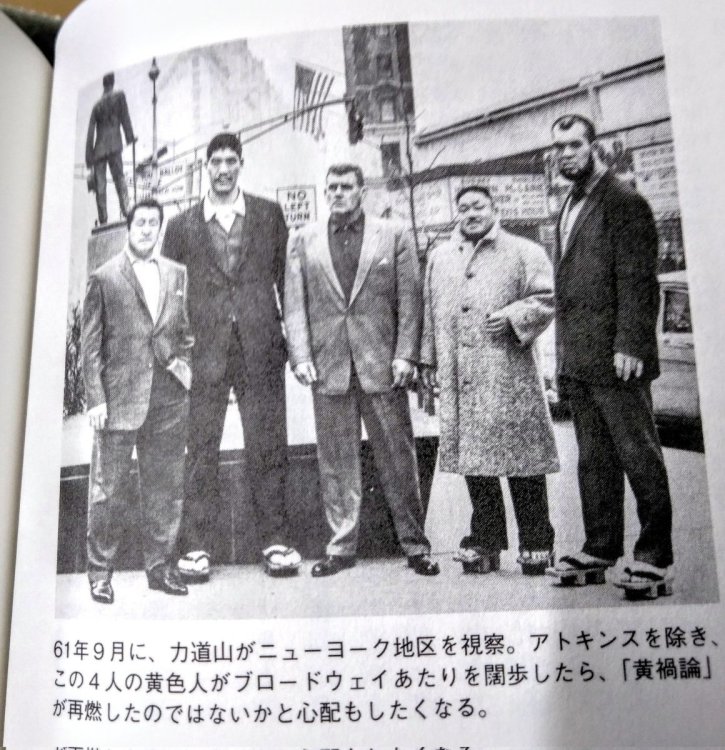

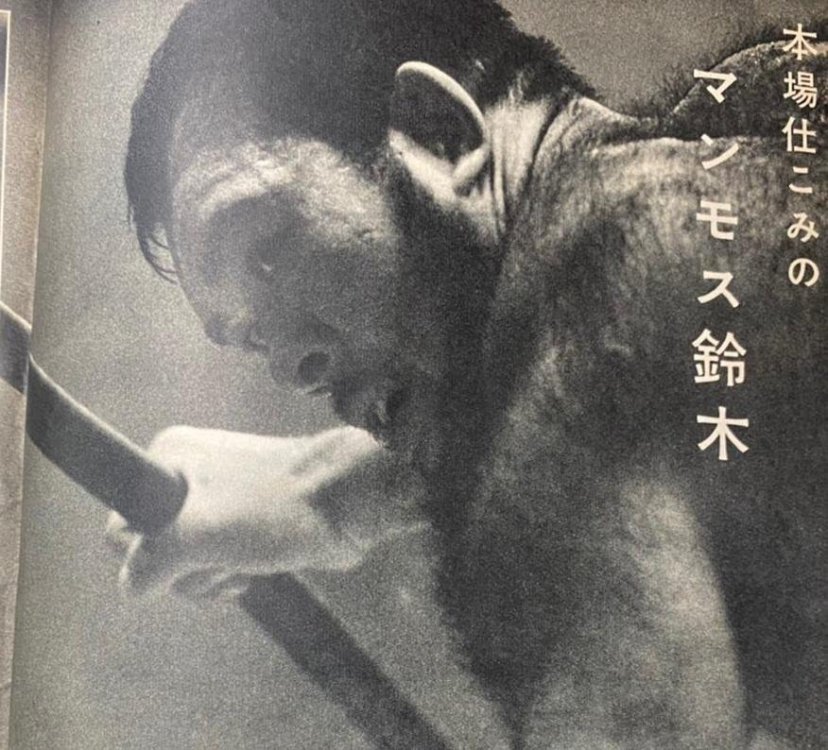

Mammoth Suzuki (マンモス鈴木) Profession: Wrestler, Referee Real name: Yukio Suzuki (鈴木幸雄) Professional names: Yukio Suzuki, Mammoth Suzuki, Gorilla Suzuki Life: 2/10/1941-5/24/1991 Born: Sendai, Miyagi, Japan Career: 1959-1981 Height/Weight: 193cm/120kg (6’4”/260lbs.) Signature moves: chop Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, Tokyo Pro Wrestling, International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Mammoth Suzuki was puroresu’s first big bust, starkly disappointing high expectations from Rikidozan in the early 1960s. He then returned to the business, holding a lengthy tenure as an IWE referee. Born to an affluent family, Yukio Suzuki entered the Dewanoumi sumo stable at the beginning of 1956. He does not appear in any sumo records, though, because he quickly deserted them. It became a legend in Dewanoumi, as Yukio took a cab some 220 miles back home and told the driver to bill the stable. (The bill ended up with his family.) Some time later, Suzuki was introduced to Rikidozan through the owner of the Morisue Ryokan, a Sendai hotel which the JWA regularly booked. He officially joined on February 27, 1958, as one of the JWA’s earliest trainees without any substantial experience in sumo, judo, or amateur wrestling. Suzuki’s 193-centimeter frame made him a valuable prospect; the only JWA alumnus up to that point who stood taller was 203 cm (6’8”) Taiwanese ex-sumo Rashomon Tsunagoro. Yukio debuted under his real name on September 5, 1958. At the Kuramae Kokugikan, he went over Tony Alford, an American serviceman who had been stationed in Japan for a decade and would work as a JWA referee in the early sixties. This match was broadcast live on the premiere of the JWA’s Mitsubishi Diamond Hour program with Nippon Television. Alongside Shohei Baba, Kanji Inoki, and Kintaro Oki, all of whom joined after him, Suzuki was part of the first quartet in puroresu to be nicknamed the shitenno (Four Pillars). As Junzo Yoshinosato later recalled, Rikidozan once thought that Suzuki was the likeliest among them to succeed. Reporter Teiji Kojima, who later provided color commentary for the IWE’s joshi division, strongly promoted Suzuki in his writing. But problems soon emerged. Rikidozan, Baba, Fred Atkins, Great Togo, and Suzuki in New York City, circa September 1961. Suzuki was originally supposed to accompany Rikidozan on his second trip to Brazil in 1960, but he ran off at the terminal. In May, he received the ring name Mammoth Suzuki, but he abandoned the promotion after a match against Yoshinosato on July 9. An article on his comeback in the February 1961 issue of Pro Wrestling & Boxing confirms that he was absent during this period, as opposed to just not covered in the incomplete records of the period. When he returned on January 8, he lost a singles match against Shohei Baba, and lost his ring name as a result. The two giants wrestled as a tag team, and on July 1, they and Yoshinosato left for an American excursion. The trio first worked in Los Angeles for Jules Strongbow's North American Wrestling Alliance, soon to be renamed the Worldwide Wrestling Associates. Then, they flew to the Northeast, under the wing of Fred Atkins, to work for the Capitol Wrestling Corporation. Notably, Suzuki was the first to wrestle Bruno Sammartino and Johnny Valentine in the latter territory, losing singles matches to them as Baba was elevated by jobbers. The three returned to Los Angeles in October, as Strongbow prepared for a show war against hotshot San Francisco promoter Roy Shire. Baba and Suzuki wrestled each other to open an October 6 show at the Memorial Sports Arena, booked the day before Shire’s show. Baba and Yoshinosato returned to the Northeast after a show in San Bernardino the next day, while Suzuki remained in the territory until mid-January. Strongbow clearly didn’t have much use for him, though, as Suzuki was never booked for his flagship venue, the Olympic Auditorium, after his original NAWA run that summer. Instead, Strongbow relegated him to house shows and even sent him to Phoenix and San Francisco. (He worked for Joe Malcewicz in the latter town.) Suzuki had a resurgence when he returned to the Northeast in early 1962, as he and Baba teamed up. But on May 30, Suzuki suddenly returned to Japan. Journalist Etsuji Koizumi states that this was to avoid charges after he had struck a female fan in private. Koizumi also points out that Suzuki's departure was important for Baba's rise. In a July match, Baba was encouraged to perform a big boot by his partner Skull Murphy. This kick, named the “16-bun” kick in Japan (after Baba's shoe size), was not just to become a signature maneuver, but a marketing cornerstone. In one of his first matches back, he wrestled Inoki on June 16. Inoki implied in his autobiography that the time-limit draw that ensued was him going into business for himself, to Rikidozan’s anger. Suzuki earned the right to wrestle as Mammoth again that summer. He won his first JWA match against a major gaikokujin in July against Duke Hoffman and went the distance with the likes of Kokichi Endo and Ricky Waldo. However, after a match that autumn his career took a turn for the worse. Suzuki's poor performance in an infamous six-man tag set the tone for the rest of his JWA tenure. On September 21 in Otsu, Suzuki teamed up with Rikidozan and Toyonobori to wrestle Moose Cholak, Skull Murphy, and Art Mahalik. This match came one week after Cholak had legitimately injured Rikidozan's shoulder in the postmatch fracas of his tag title defense. The ace had taken four days off; he only returned when pressured by the promoter of a two-night run in Osaka and wore a football shoulder pad borrowed from his son Yoshihiro. The pressure was on Suzuki to carry his weight as the lower-ranked wrestler in peril in this televised tag, and he blew it, badly. He was dominated by the foreign team, never managing to put them on the back foot, and looked "gutless" to both the building and the TV audience. After the match, Rikidozan beat Suzuki in the ring and urged Toyonobori to join with a slap. As Koizumi writes, this audible allowed Rikidozan to cover up his poor performance that night, as the theme of the tour became a waiting game for when he would remove the shoulder pad. Suzuki continued to disappoint, which culminated in a remarkably petty display when Rikidozan renamed him Gorilla Suzuki in the middle of the 1963 World Big League tour. Suzuki retired that year for health reasons and underwent pituitary surgery the following year. Left: Suzuki during his time as an IWE referee. [Source: Deluxe Pro Wrestling, January 1980] Suzuki returned to wrestling at the invitation of Toyonobori when Tokyo Pro Wrestling started up. He stayed on board as it merged with the IWE, wrestling on the undercards (sometimes in a mask) through the start of 1969. After that, Suzuki remained with the company as a referee until its closure. Suzuki introduced the IWE to one of its major sponsors. Fukoku Oil, based in Numazu, manufactured and sold industrial goods made from petroleum. Fukoku sponsored the IWE for six years until the promotion's collapse, and they were advertised on their ring aprons. In parallel with his refereeing career, Suzuki also found work as an actor throughout the seventies. The most notable production he appeared in was the 1977 tokusatsu film and Star Wars response The War in Space, where he played the horned Chewbacca knockoff Uchūjūjin. On August 9, 1981, Suzuki officiated the IWE's last match, a wire mesh deathmatch between Goro Tsurumi and Terry Gibbs. That was his last involvement in the business. Suzuki died of internal disease in 1991, while hospitalized in Shiogama. Suzuki as Uchūjūjin in The War in Space.

-

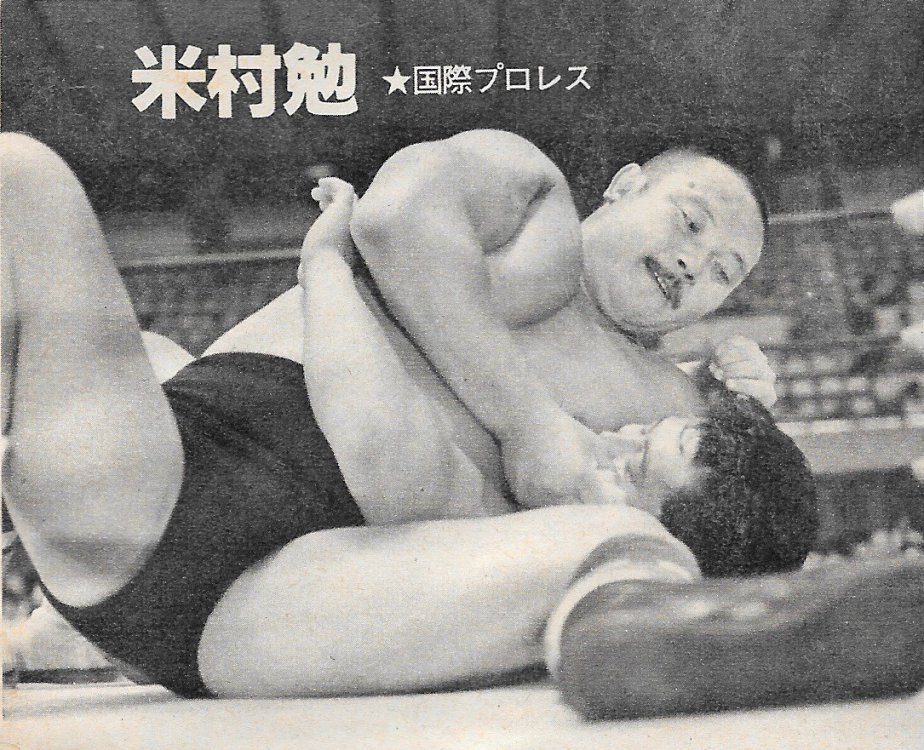

Tenshin Yonemura (米村天心) Real name: Tsutomu Yonemura (米村勉) Professional names: Tsutomu Yonemura, Tenshin Yonemura Life: 12/16/1946-6/20/2016 Born: Kasumi District, Akita, Japan Career: 1972-1996 Height/Weight: 179cm/110kg (5'10";242 lbs.) Signature moves: Bear hug Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Tenshin Yonemura was an undercarder for the IWE who remained in the business afterward through shows in his city. Tsutomu Yonemura wrestled for the Takeshima sumo stable, debuting in September 1962. He eventually reached makushita under the shikona of Takanobori, but he struggled to perform well and retired after the first tournament of 1969. After this, Yonemura found work as a trainer in the bodybuilding gym of former lightweight weightlifting champion and onetime JWA wrestler Takao Kaneko. At Kaneko’s recommendation, Yonemura would join the IWE in June 1972. He was a quick study, debuting in September. Stylistically, Yonemura was a “rough” fighter who admired Dick the Bruiser. Profiles in the Showa Puroresu fanzine recall that Yonemura could be seen accompanying gaikokujin to the ring as a second while wearing their shirt. While seen as a promising candidate for an overseas expedition, Yonemura never got the chance. In spring 1980, he was rechristened Tenshin Yonemura. After the IWE folded, Yonemura opened a chanko restaurant in Aizu-Wakamatsu. He would never wrestle fulltime again, but he aligned himself with the All Japan wing of his former promotion, making one or two special appearances a year when the promotion stopped by. This lasted until 1987, but even this wasn’t quite the end of Yonemura’s career, as he made appearances at local shows in the early 1990s. Cagematch records two of these: an SWS show in February 1992 and an Oriental Pro show in February 1993. However, Japanese sources state that he appeared for other promotions such as Goro Tsurumi's IWA Kakutō Shijuku, and that his final match was in 1996, two years after his retirement date as claimed by Cagematch. Yonemura was also responsible for introducing future AJPW wrestler Kazushi Miyamoto to Giant Baba, as Miyamoto was a member of his son's sumo club. Yonemura died on June 2, 2016. AJPW visits Yonemura's Yagura Taiko restaurant (circa late 1980s).

-

Snake Amami (スネーク奄美) Real name: Isamu Sakae (栄勇) Professional names: Isamu Sakae, Snake Amami Life: 5/25/1951-4/30/1981 Born: Hioki District (present-day Minamisatsuma), Kagoshima, Japan Career: 1972-1981 Height/Weight: 174cm/92kg (5’8”/202 lbs.) Signature moves: Diving crossbody Promotions: International Wrestling Enterprise Titles: none Snake Amami wrestled for the IWE for seven years as an undercarder, before a brain tumor led to retirement and an early death. After graduating from junior high, Isamu Sakae entered the Isutzu sumo stable, debuting in January 1967 at the age of 15. He reached sandanme (third rank) before retiring after the first tournament of 1970. Sakae decided to go back to school after this, enrolling in the Kagoshima High School of Commerce and Industry (now Shonan High School). Here, he devoted his athletic pursuits to amateur wrestling, and in 1970, he won both interhigh and nationals in the freestyle 75kg division. He would travel to the United States in a Japan-US competition, where he notched eleven wins and one draw. Upon his graduation, Sakae joined the IWE sales department in 1972. However, he would train to wrestle with the company, debuting in the new year. Sakae served as Rusher Kimura’s valet, and the two became very close. Kimura's stepson Hiroshi would remember Sakae as the best person he ever met in the business. Rechristened Snake Amami in 1974, he was an undercarder whose combination of wrestling technique and aerial attacks was an appealing combination. At the 1979 Tokyo Sports show, Amami put over NJPW's Makoto Arakawa in the second match. Shortly into the new decade, though, Amami was forced to leave when a brain tumor was discovered. Despite a brief attempt to return that September, he never wrestled again, and died the following spring. At his wake, Kimura spent the night to sleep with his departed friend, and after the IWE’s final show in August, the roster stopped by Amami’s home on their way back to Tokyo to light incense. For the rest of his career, Kimura would decline all offers to take on another valet.

-

Surugaumi (駿河海) Real name: Mitsuo Sugiyama (杉山光男) Professional names: Surugaumi Life: 1/1/1920-11/24/2010 Born: Shizuoka, Shizuoka, Japan Career: 1953-1959, 1961 Height/Weight: 186cm/105kg (6'1"/231lbs.) Signature moves: unknown Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association Titles: Japanese Junior Heavyweight [JWA] (1x) The first junior heavyweight champion in puroresu history, Surugaumi was a charter member of the JWA whose disputes with Rikidozan shortened his career. Mitsuo Sugiyama entered sumo through the Kansai Kakuriki Association, an organization which was formed by Saburo Tenryu after he left the Japan Sumo Association. (This was rooted in the 1932 Chunjuen Incident, in which Tenryu led 32 rikishi in a strike against the Association.) Kansai Kakuriki folded in December 1937, and Sugiyama debuted for the Japan Sumo Association’s Dewanoumi stable in January 1938, but I do not know if this was actually his tournament debut, or if Kansai Kakuriki’s tournament results were simply lost. Adopting the shikona of Surugaumi in May 1939, he rose through the ranks in the following years, nicknamed the “blue devil” to the promising Shionoumi’s “red devil”. However, a knee injury derailed his career, and Surugaumi retired after the November 1945 tournament. Sugiyama (center) circa 1957. After leaving sumo, Surugaumi managed a small restaurant for years until he was invited to join the nascent JWA by Rikidozan. According to The Face of the Box Office, a 2004 book on JWA supporter and live entertainment don Sadao Nagata, Surugaumi assisted in the construction of the Japan Pro Wrestling Center in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, which contained the JWA’s original dojo. As one of its charter members, Surugaumi would become the JWA’s first junior heavyweight champion in 1956, when the JWA organized three interpromotional brackets in the junior, light, and heavyweight classes. In the final match of the bracket, Surugaumi defeated Michiaki Yoshimura, star of the Yamaguchi Dojo promotion (which was basically what remained of the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association after their yakuza boss sponsor withdrew his support). However, Yoshimura himself would be hired by Rikidozan the following year for three million yen, and Surugaumi’s spot was soon taken. Surugaumi and Yoshimura were early fixtures of puroresu’s first weekly television program, Nippon Television’s Puroresu Fight Man Hour. On its very first episode, he lost the title to Yoshimura, who at that point was billed as a freelancer but was already hired. Yoshimura, not Rikidozan, would become the star of the program, in an arrangement which G Spirits writer Etsuji Koizumi compares to the role that Verne Gagne had played vis-à-vis Lou Thesz in the “Chicago model” of the early 1950s. Yoshimura was also pegged as the star of another weekly program planned to tape in Osaka (where the All Japan Association had been based). Both Puroresu Fight Man Hour and the Osaka Pro-Wrestling Hour (which debuted in December) were attempts to compensate for the massive financial hit that the JWA had taken by cutting ties with Sadao Nagata, on whom they had solely depended to book house shows. This is important to note because, according to the first part of Etsuji Koizumi's biographical serial about Yoshimura (G Spirits Vol. 62), it led to the end of Surugaumi’s career. Alongside Azumafuji, Surugaumi persistently nagged Rikidozan about payments, until Rikidozan ordered Yoshimura to shoot on Surugaumi’s bad knee during a match. Both Surugaumi and Azumafuji officially retired in 1959, and Surugaumi never received all of his money. According to Yoshimura's 1973 autobiography Konjo, Surugaumi eventually ran a supermarket in Ishikawa. In April 1961, he came out of retirement to wrestle a final pair of shows in Seoul, alongside former coworkers Takao Kaneko and Osamu Abe. Sugiyama died of intestinal obstruction in 2010. At that point, he was the oldest surviving man in puroresu, but he has since been passed by Kokichi Endo. who as of writing is presumed still alive at 96. Surugaumi takes a dropkick from Yoshimura.

-