-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

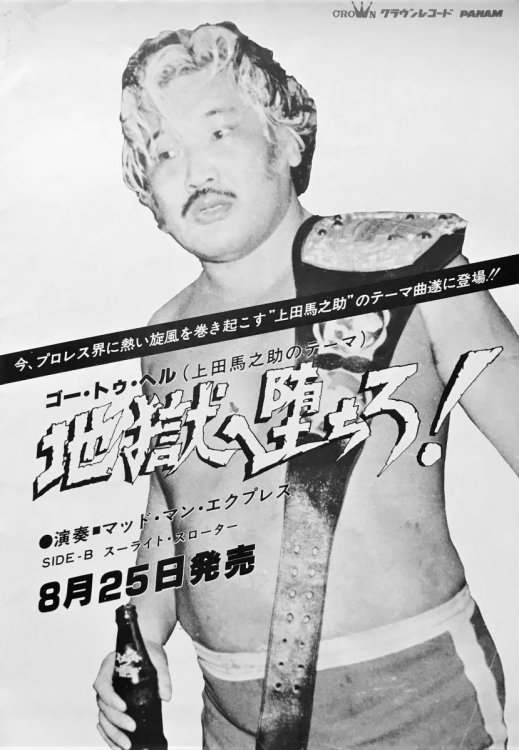

I am four thousand words into a Deluxe Profile on Killer Khan, which will essentially adapt his 2018 autobiography. Just about finished with his JWA tenure.

-

UPDATES, DECEMBER 2023 My last profile of the year was the longest I have yet written: a 16,000-word behemoth on puroresu's first great worker. Michiaki Yoshimura (Wrestler/Executive/Booker, AJPWA/JWA) [DELUXE PROFILE #3] ------ For 2024, I plan to write a profile for the recently departed Killer Khan, with his autobiography as a primary source. I also have the autobiography of the Great Kabuki and would like to give him similar treatment. Another profile I have planned is for Umeyuki Kiyomigawa. Excluding Rikidozan, who I am far from ready to write a profile for, and Masahiko Kimura, who I am arguably unqualified to write about, Kiyomigawa is the most notable figure of early mens' puroresu that I have not yet written about.

-

I just got an ebook of Khan's autobiography for cheap. I can't promise a quick turnaround but I'm going to give him a profile on here.

-

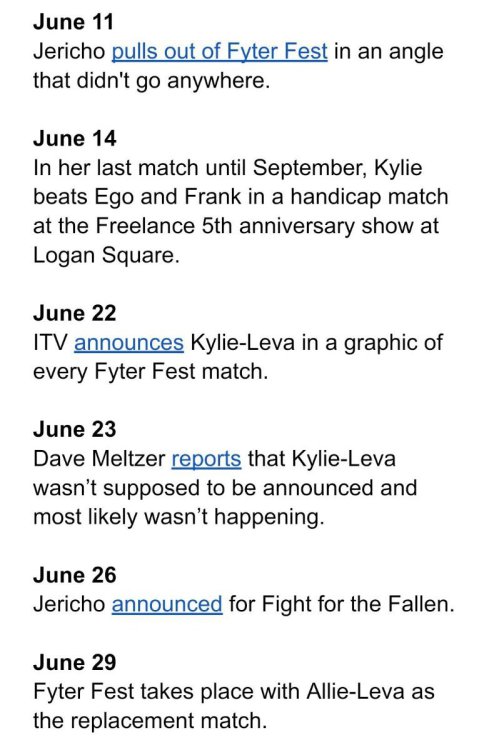

Someone I follow on Xitter pointed out all of this stuff leading up to Fyter Fest 2019. It's all speculation at this point, but I haven't been able to stop thinking about it.

-

RIP. Plugging the 1979 article that I translated last year, about his brother's ill-fated wrestling career and how that inspired Osamu to finish what he had started.

-

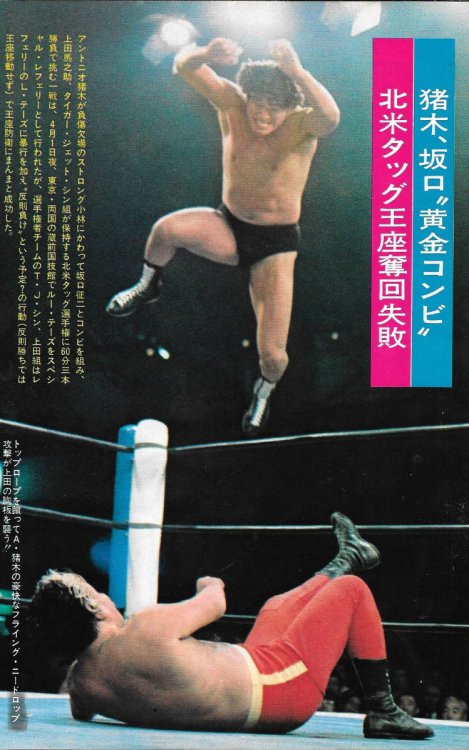

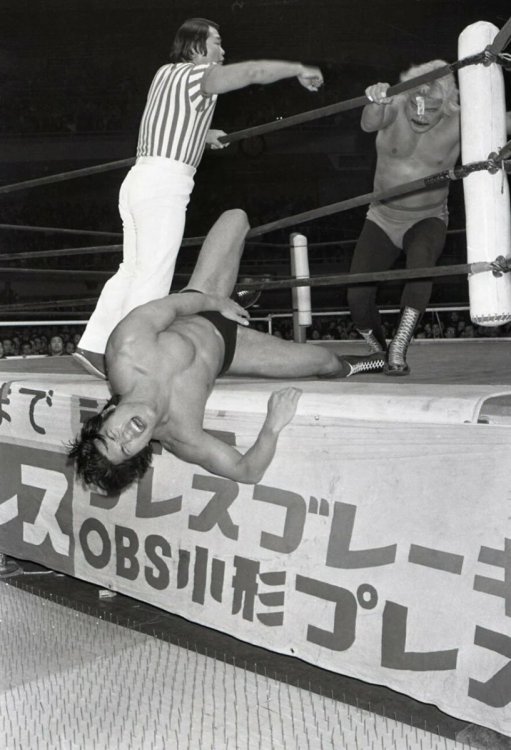

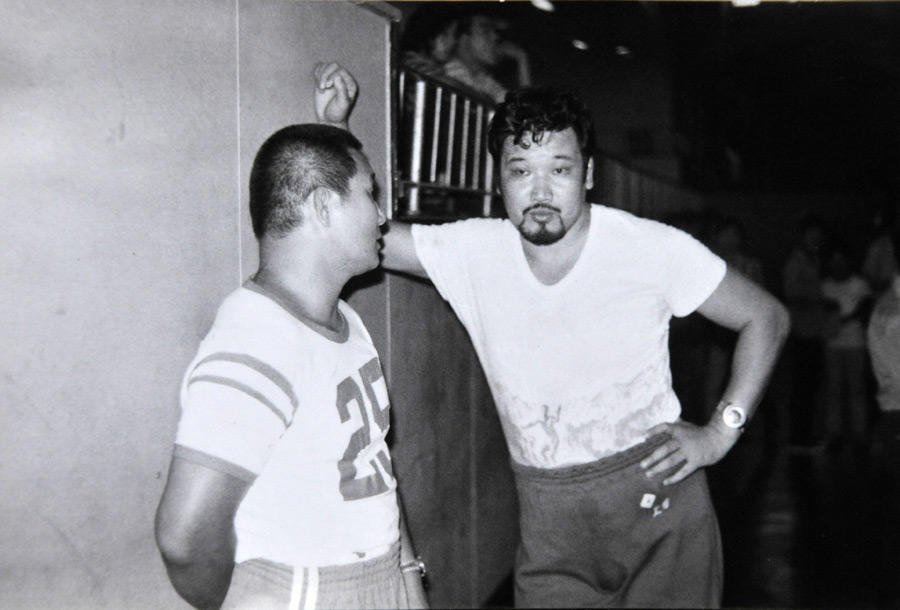

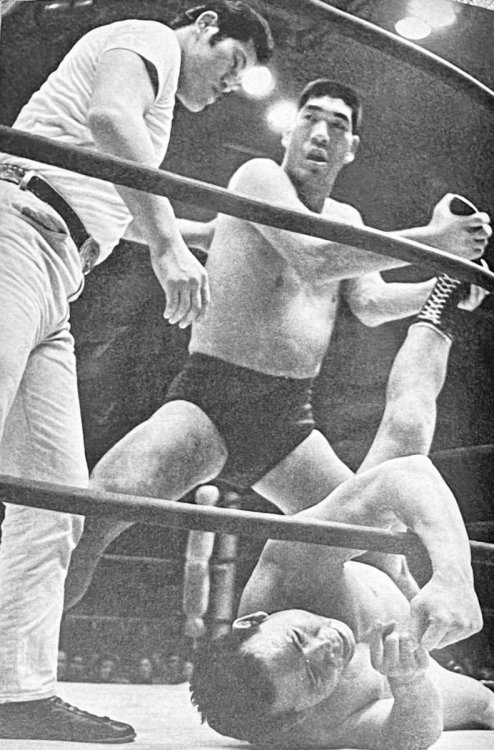

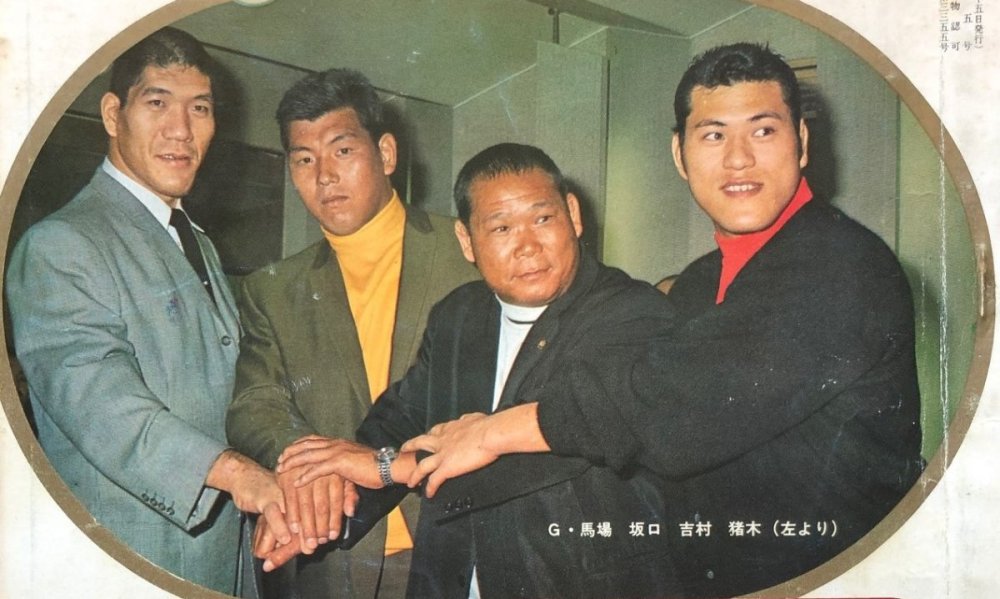

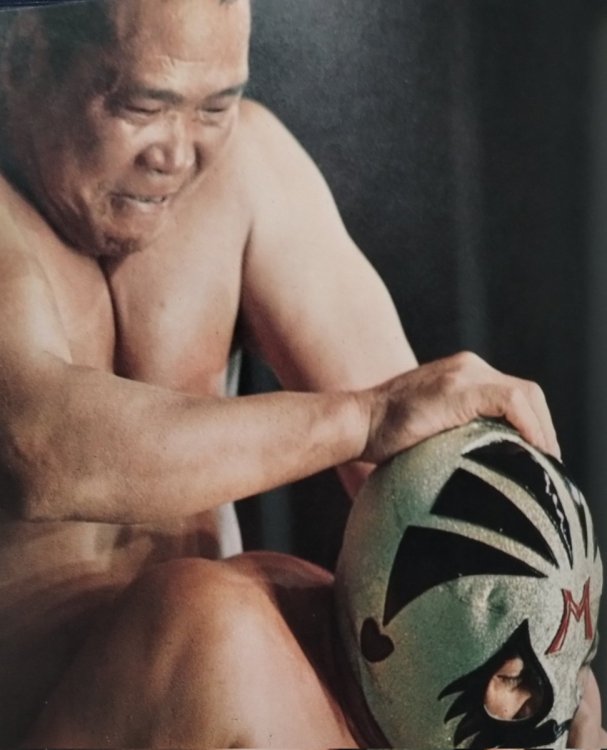

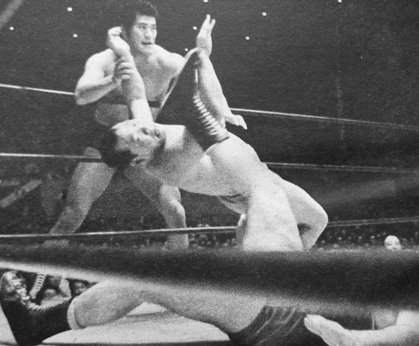

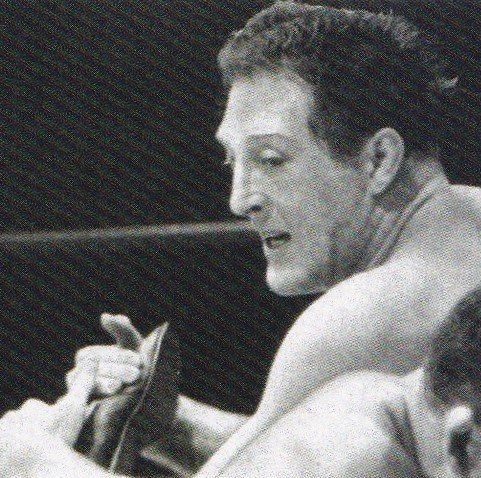

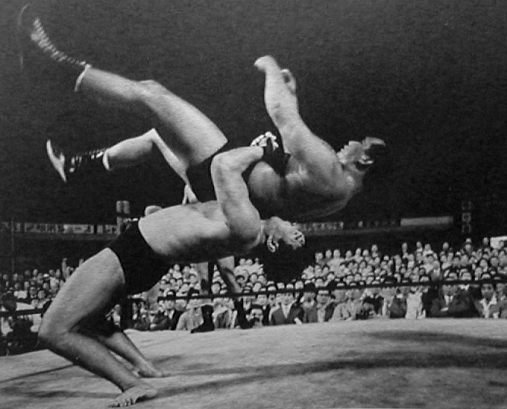

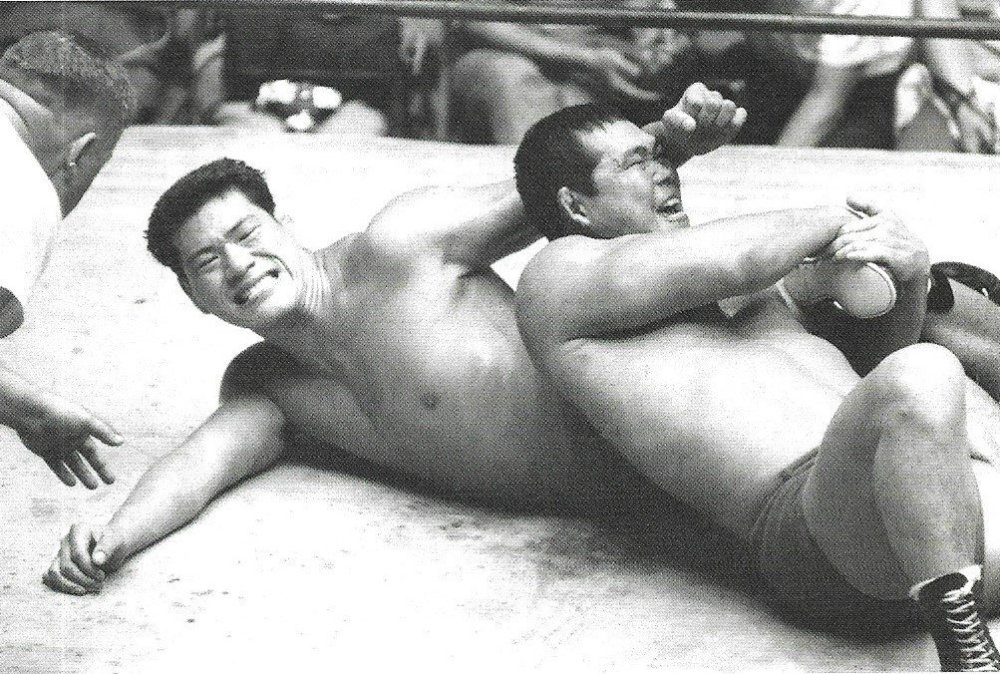

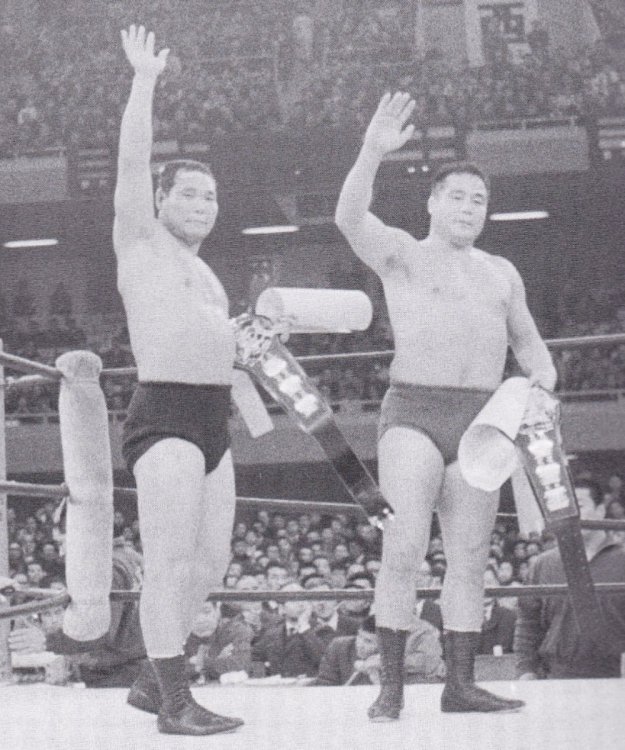

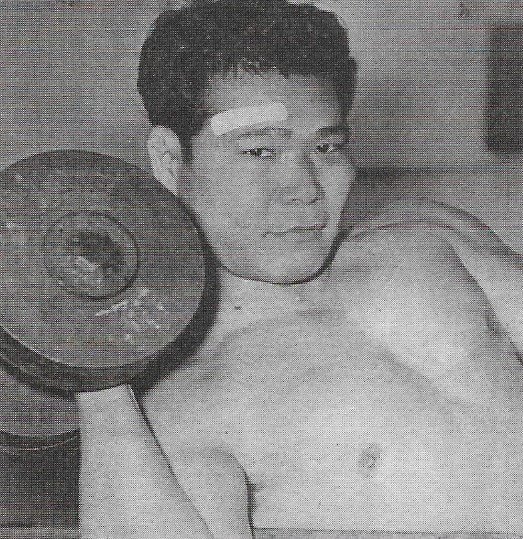

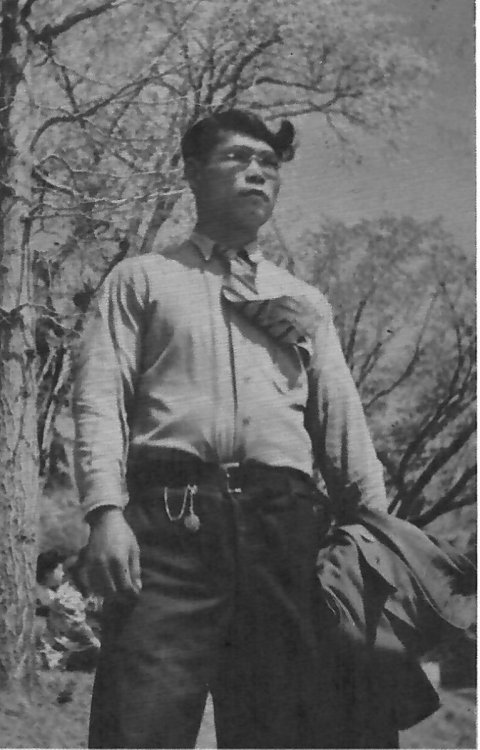

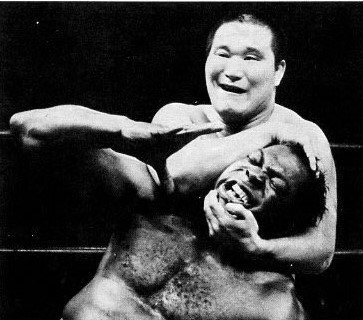

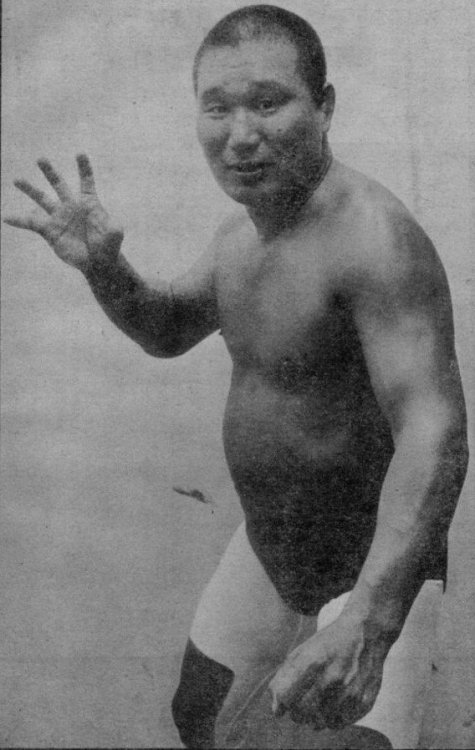

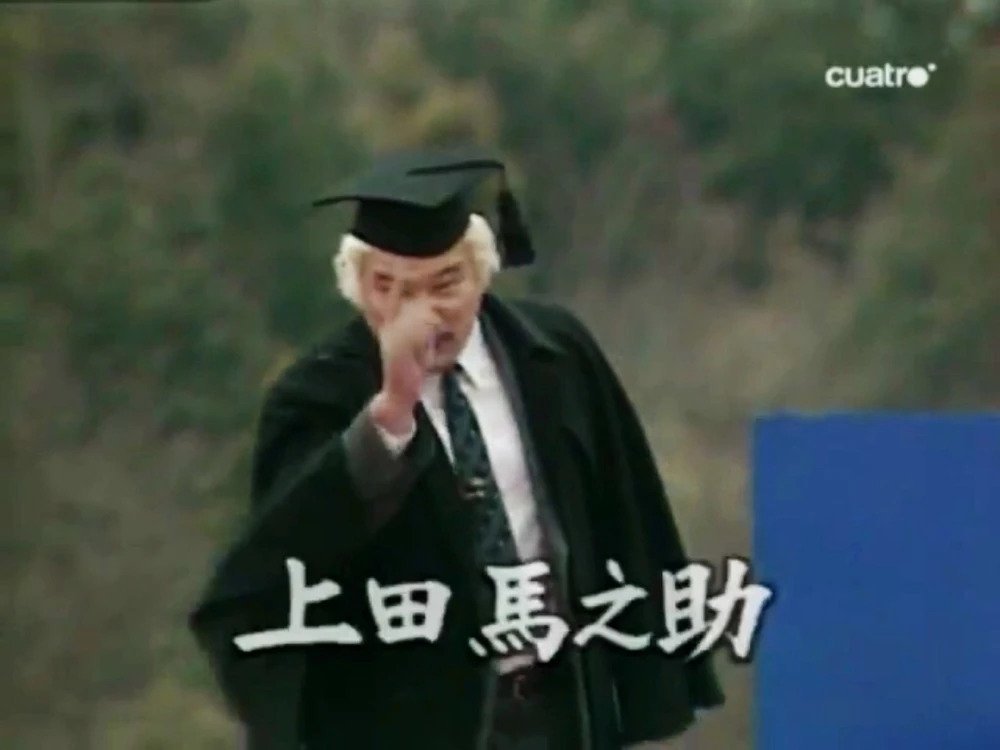

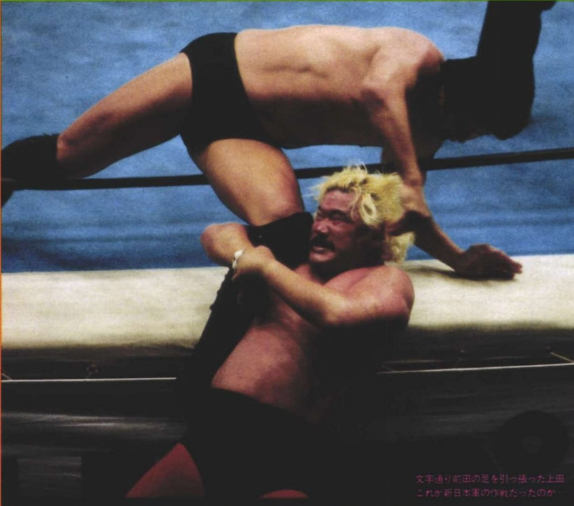

PART FOUR: FIGHTING GENERAL (1967-1973) Yoshimura was a double champion for over half of 1967. On the year’s first tour, he defended the All Asia titles twice against teams centered on the aging Mr. Atomic, while he and Baba went to a broadway with Atomic and Buddy Austin. The following MSG Series is most famous for Baba’s pair of draws against close friend Bruno Sammartino, but Baba & Yoshimura also defended against Austin & Hans Schmidt on that tour. Underneath the second of Baba & Sammartino’s matches, Yoshimura & Oki wrestled the same opponents in a non-title match. Besides the very final Yoshimura match in circulation, this is the only surviving match of his team with Oki. The 9th World League pushed the returning Destroyer and Waldo von Erich as its foreign favorites. As Oki left the tour after only working three of his tournament matches, plus what would be a final tag defense in Osaka, Yoshimura placed second among the natives. He and Baba were neck-and-neck right up until the tour had nearly ended, when he lost against Waldo. Baba went on to beat the Destroyer in Yokohama. In retrospect, all this is overshadowed by the return of Antonio Inoki, which was announced on April 7. Inoki and most of Tokyo Pro had worked on the first tour of Yoshiwara’s new promotion, but quickly fell out with them. Through the mediation of Daily Sports reporter Masakiyo Ishikawa, Inoki had gotten an interview with Baba, which led him to negotiations with Yoshinosato. Inoki made the company agree to eight conditions for his return; this document has never been publicly released, but it is known that these conditions related to his salary and booking.2 Inoki was set to return to the ring on the following tour. With the help of his biggest money mark, South Korean president Park Chung-hee, Oki had booked a title match against WWA Heavyweight champion Mark Lewin. On April 29, he beat Lewin in Seoul.1 Most records state that the All Asia titles were vacated that month after Oki suffered a car accident. In truth, this car accident was a fictitious attempt on Oki’s part to get out of defending his new title in Los Angeles. After the WWA threatened to strip the title, he ended up going to their territory after all, and would be overseas for an All Asia defense which had already been booked as part of a two-night run in Sapporo. Oki was fine with that title being vacated, and had suggested that Yoshimura team up with Umanosuke Ueda, then working as Great Ito. What Oki did not want was for Yoshimura to team up with Inoki. Guess which of these happened. Three days after Baba & Yoshimura defended the International tag titles against Waldo & Fritz von Erich in Osaka, Inoki was slotted in for the All Asia match against Waldo & Ike Eakins. He and Yoshimura were attacked before their entrance had finished, and the bell rang as they brawled around the arena, at first still in their gowns. With the help of a chair, Inoki got enough time to finally enter the ring, but Waldo brought out a foreign object and hit both men. Oki Shikina ruled the first fall as a DQ, in just under six minutes. The second fall began with another scuffle by the announce table, before Inoki & Yoshimura rolled back into the ring. Once in the ring, Yoshimura dropkicked Waldo off the apron and tagged in Inoki, who took it to Waldo, and then Eakins, with his signature “knuckle arrow” punches. Back between the ropes, Inoki got Eakins in the cobra twist, but Waldo broke it with a punch. As Inoki tagged out to introduce Waldo to the ring post, Yoshimura laid Eakins out with a dropkick for the win at 13:18. Yoshimura was a double champ again, and he remained so throughout summer 1967. It was a notable summer for the JWA, if not for him in particular. In response to the IWE’s second tour, they booked NWA champion Gene Kiniski to challenge for Baba’s International Heavyweight title, running that match in the mortar bowl-shaped Osaka Stadium opposite the IWE’s show at the Prefectural Gymnasium. That fall, the plan was put in motion for Yoshimura to step back, and for Baba & Inoki to team up. On October 6 in Fukushima, Baba & Yoshimura dropped the International tag titles to Bill Watts & Tarzan Tyler. Yoshimura took a week off to sell a cracked rib from Watts’ Oklahoma Stampede. When Baba & Inoki won the titles back on October 6, the B-I era began, and Inoki vacated the All Asia titles. On January 6, 1968, Yoshimura and Oki revived their All Asia duo when they beat Bill Miller & Ricky Hunter for the belts. That was the first of a two-night stint in Osaka, after which the boys flew to Hiroshima for a Hiroshima show on the 8th. Inoki took a flight back to Tokyo due to an issue with his common-law wife, Diana, and planned to fly back in time for the show.3 Alas, his flight back was canceled due to a snowstorm. A tag title defense had been scheduled that night, so Baba & Yoshimura reunited to challenge Miller & Crusher Lisowski. The match went to a double countout in the third fall to keep the belts held up. When the tour ended in Tokyo, Baba & Inoki went over that team to win them back. In the meantime, Oki turned in his resignation on January 17, and then attempted to jump ship to the IWE, then under its short-lived rebrand as TBS Pro Wrestling. He flew to Sendai for their show that night, but was threatened not to show up, and quickly reinstated.4 He and Yoshimura mounted another All Asia defense near the end of the tour. The next tour kicked off at Korakuen Hall on February 16, but there was a major problem: the six foreigners set to fly in had been snowed out of Haneda Airport. That night, the JWA held a six-match card of native vs native matches. In the main event, with Inoki sitting in as referee, Baba beat Yoshimura with a backslide in 15:36. It was Yoshimura’s last match against one of the three stars he had fought off so many times in the early sixties. That tour, the Dynamite Series, marked the start of Mitsubishi Diamond Hour’s exclusive residence at the Friday 8PM timeslot, which was a response to the IWE’s new weekly broadcasts. (Disney was moved to another night.) Notably, it also saw the Japanese debuts of Harley Race and Dick Murdoch. In an interview with Koji Miyamoto shortly before his death, Race remarked that Yoshimura was the best wrestler in the company, as he was “several steps ahead” of Baba and Inoki when it came to carrying a match, and Race could say “with confidence” that he never had a bad one with him. Koizumi makes an interesting point. The singles matches that Yoshimura had wrestled against younger talent, holding the line to the upper card, had ceased after Rikidozan’s death. However, Koizumi believes that Yoshimura fulfilled this role for foreigners in his later career, guiding young and hungry B-class players with a solid hand. Koizumi also regards this period as a high point for Yoshimura as a booker, such as his push of Buster Lloyd (Rufus R. Jones) in early 1969. That saw Lloyd go over Oki in a buildup singles match, where Oki’s head was still bandaged from an infamous ear-cutting incident the previous year in Sendai, and he was unable to use his headbutt.5 When the JWA ran Sendai again, Lloyd and Oki squared off in a defense of Oki’s Asia Heavyweight title. Yoshimura & Oki kept the All Asia titles for most of 1968, with only a three-week loss in July to put over Skull Murphy & Klondike Bill. Yoshimura’s last match in Korea was a defense that November against Buddy Austin & Red Bastien. Like their first, their third reign was vacated, but it was not Oki who would be unavailable. Yoshimura left for the United States in January 1969, and Oki teamed up with Inoki to win the titles instead. After the IWE’s relationship with booker Great Togo had soured the previous year, Togo had a plan to form his own Japanese promotion with the supposed backing of Lou Thesz. Kokichi Endo started negotiations for a second television program with the NET TV network, which was prepared to work with Togo if the deal fell through. Yoshimura’s job, evidently, was to prevent Togo from trying what he had with Oki the previous year. As Koizumi concludes, Michiaki worked a scattered series of dates across the United States primarily to meet with and secure the loyalties of overseas talent that were working in those territories, but also to book some gaikokujin. Yoshimura started with a match in Los Angeles against Harley Race on January 23. Three weeks later, he was in Detroit. Great Kojika was working for Ed Farhat at the time, so Yoshimura teamed up with him and Duke Keomuka on February 15. After that, Yoshimura and Keomuka went down to Fritz von Erich’s territory, where Yoshimura worked a week of dates while negotiating for Fritz’s return to Japan. He then followed Keomuka to Florida, where he met with Seiji Sakaguchi. The two wrestled as a team in West Palm Beach, and then, in Yoshimura’s final match in the US, in Los Angeles. Finally, on March 18, he and Sakaguchi returned to Japan. The 11th World League was booked with the knowledge that the JWA had a new TV program coming in July. Nippon Television laid out several conditions for their approval of another network deal, the most important of which was their exclusive rights to Baba. The program, which was to be called World Pro Wrestling, called for the JWA to develop a parallel ace. The result may have been one of Yoshimura’s greatest achievements as a booker, but he could not quite claim full credit. The World League began at Tokyo’s Kuramae Kokugikan after a warmup show in Korakuen. On the Kuramae show, Sakaguchi made his Japanese debut alongside Yoshimura in a tag against Medicos #2 & #3 (Luis Fernandez & Tony Gonzales); Koizumi speculates that Yoshimura, and possibly the Medicos as well, had given Sakaguchi further coaching in Los Angeles. Yoshimura had booked himself to a middling result the previous year but made something of a resurgence. His six points tied with Oki and edged out Sakaguchi, whose name value drew tickets but whose skills were found somewhat lacking by the higher-ups; he was sent back overseas after the tour. Gorilla Monsoon started strong, beating Baba in the first match of the tournament, but double countouts against Oki and Sakaguchi, and a loss to Inoki, set him further behind; a massive upset against Kotetsu Yamamoto followed in early May. Yoshimura himself went over finalist Bobo Brazil in a later match. At the end of the tournament, both the native and foreign sides had ties. Baba, Inoki, Brazil, and the debuting Chris Markoff – who Yoshimura had scouted while overseas, alongside Bobby Duncum – all had 6.5 points. On May 16, at the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium, a coin flip decided which native would wrestle which foreigner; it was made clear that if a tie remained after these two decision matches, a further decision match would take place regardless of sides. After Baba and Brazil dragged each other out to a half-hour draw, Inoki debuted the octopus stretch he had previously demonstrated to win the World League. Alongside Endo, referee Yusuf Turk had lobbied for Inoki to win the tournament, and as he confirmed to Koizumi near the end of his life, it was he, and not Yoshimura, who booked Inoki’s final match against Markoff. Inoki & Oki had won the All Asia titles from Buster Lloyd & Tom Jones in February, but they vacated the belts after just two defenses. This was partially so that Oki could defend his singles title on the same show as an All Asia defense, but according to Koizumi, it was also because the two just did not mesh well as a unit. So it happened that puroresu’s greatest supporting wrestler booked himself for a second run with Inoki. In fact, when World Pro Wrestling premiered on July 22, its first episode (from the June 23 show in Ota) featured an Oki singles match (against Eric von Stroheim), and an Inoki-Yoshimura tag against the Steiger brothers. On August 9 in Nagoya, Inoki & Yoshimura beat Crusher Lisowski & Art Michalik. The major roadblock came that fall, when they fought Mr. Atomic & Buddy Austin in a trio of defenses. In Osaka on September 27, the heels bloodied Yoshimura with a weapon and won the first fall with an Atomic neckbreaker, but a cobra twist from Inoki and a Yoshimura rolling clutch won the day. On October 10 in Yamagata, Atomic had Yoshimura in another neckbreaker in the final fall, but Inoki reached out and grabbed Yoshimura’s forearm to keep him standing. After the challengers complained about the pinfall that resulted, the belts were actually held up for a final match in Yoshimura’s hometown. On October 30, the champions won them back. If one discounts his three years with a junior heavyweight championship that he only defended for less than one, this third run with Inoki was to be the longest title reign of Michiaki’s career. Gene Kiniski, Harley Race, Johnny Valentine, and the Assassins were just a few of the challengers that they fought off. The 12th World League was a step down from the heights of the previous year and reverted to a Baba victory. Baba could not put Don Leo Jonathan away clean in the final, as he hit himself in the groin on the ropes with a missed dropkick. (Inoki got a pinfall on Jonathan in the tournament itself but had choked in a Markoff rematch.) The problem was not just with the booking, though. With two television programs arguably oversaturating the product, not to mention the coverage of the six-month Expo ‘70 world fair, Koizumi claims there was a dip in attendance, one which Sakaguchi’s return did little to help. From the start of the World League, World Pro Wrestling changed from a taped show at 9PM on Wednesdays, to a live broadcast at 8PM on Mondays. This switch only caused further headaches for the booker. On taping dates, Yoshimura was now forced to slot Baba in the midcard so that his match was finished before cameras started rolling. Anyone would struggle to book a good show under such conditions. As for the man himself, Yoshimura suffered a legitimate rib injury during a tournament match against Tarzan Tyler. After this, the 43-year-old lightened his schedule to wrestle less than half of the JWA’s shows. He moonlighted as a color commentator on World Pro Wrestling, a seat that Endo and Yoshinosato also filled. Yoshimura can be heard calling Inoki’s classic match against Jack Brisco from August 1971. Yoshimura and Sakaguchi at the River Thames, near the Tower Bridge. Yoshimura wrestled his last match abroad in summer 1970, when he and Sakaguchi traveled to London to work a show for Dale Martin. Koizumi claims that this came about because ITV wanted to “introduce Japan” on the television program World of Sport. It is also worth noting that it was Martin who had approached the JWA, and not Leeds-based promoter George de Relwyskow, who had booked British talent for the IWE in the late sixties. It is very likely that the pair were scouting for a wrestler worth promoting as a foreign rival for Sakaguchi. In Croydon on July 21, Seiji beat Pat Roach, soon to shoot his film debut in A Clockwork Orange, in a round match. Yoshimura, for his part, won against Hans Steiger by disqualification. Sakaguchi left for a third excursion in September. That was when the JWA began its first NWA Tag Team League. NET wanted a tournament which would parallel the World League while spotlighting Inoki. The only problem with this was that the company’s most popular tag team was one that literally could not appear on World Pro Wrestling. Baba and Inoki were thus paired with midcarders Mitsu Hirai and Kantaro Hoshino, while Yoshimura teamed up with his former valet Great Kojika. The following year's second league was an improvement over the tournament’s maiden voyage, at least in conception. The experiment of pairing top stars with midcarders was abandoned in favor of a pair of clear favorites. While Inoki and the returning Sakaguchi gave a first glimpse of NJPW’s future Golden Team, Baba revived his double-champion duo with Yoshimura. Where that tour faltered was in the challengers. On the second tour of 1971, the JWA booked two wrestlers who had topped an IWE fan poll the previous spring: Spiros Arion and Mil Mascaras. As Yoshimura had scaled back his appearances by this point, he would not have a singles match with Mascaras until the following summer, when the luchador made his final JWA appearances. But he left an impression. At the start of 1978, Mascaras won the Best Bout Award from Tokyo Sports for the 1977 “Idol Showdown” against Jumbo Tsuruta. He proceeded to admit privately to Tsutomu Shimizu that Jumbo was still green compared to Yoshimura, who he wished he could have worked with in his prime. For the 13th World League, NTV lifted one of their original restrictions and allowed World Pro Wrestling to broadcast matches from the tournament. This iteration, and the final one which followed in 1972, changed the format. Double countouts no longer awarded half a point to both men, but more importantly, there would now be a double round-robin. Just a few days into the tour, at an April 7 show in Osaka, Inoki complained to the press that the booking was unfair; he had been forced to wrestle three League matches on consecutive shows, two of which were against star gaikokujin Abdullah the Butcher and the Destroyer, before Baba had even wrestled one. Yoshimura was reportedly furious when these remarks saw print. That booking would repeat the four-way tie of the 11th, only with the Butcher and the Destroyer as the top foreigners. On May 19 in Tokyo, Inoki and the latter wrestled first and went to a double countout. As Baba wrestled the Butcher, Inoki blindsided everyone with a backstage press conference where he went into business for himself and challenged Baba for his NWA International title. This proposal was obviously rejected, but Inoki’s refusal to retract his challenge got him over with younger fans at Baba’s expense. In fact, Yoshimura had to convince Baba to work with Inoki in a tag title defense that June. As he later recalled, by the end of the World League the locker room had clearly split into two factions supporting Baba and Inoki. As I have covered elsewhere, that all culminated in the "phantom coup" of late 1971. Much of the third part of Koizumi’s Yoshimura feature is actually devoted to Etsuji’s own theory about the “phantom coup”, which is that the accusations of managerial corruption which they hinged on were exaggerated, and that the “corporate reform” which Inoki had supposedly turned into a takeover attempt had always held that goal in mind. He believes that the official narrative of the phantom coup underplayed the role of the co-conspirators who remained with the JWA: namely, Baba and Umanosuke Ueda. Koizumi’s hypothesis hinges on a recent testimonial from Baba's valet at the time, Akio Sato, which revealed that Baba and Ueda had conducted their own investigation of the JWA's finances that summer. The theory is compelling, and it has vindicated some doubts that I have always had about the story and the discrepancies between various testimonies. To go into it would take us too far off track, but I will address one thing. The extent of Yoshimura’s corruption, as was alleged, was that he paid off reporters who covered JWA shows. Koizumi believes it is far more likely that someone wanted to take over as booker, and his best guess is Kotetsu Yamamoto. Koizumi also recounts an interesting story from before the coup, but after Yoshimura had scaled back his in-ring work. He still attended every show because it was his job to collect the money from promoters. One day, though, he was not given a train ticket, and when he went to announcer Nagaaki Shinohara, whose job it was to buy tickets, he was told that the order came from above him, but Yoshinosato knew nothing about it. Koizumi speculates that this was Baba’s attempt to take the collector job for himself.6 Now, this theory should be weighed against testimonies that Baba and Yoshimura had a strong relationship. Yoshimura's final valet, Masashi Ozawa (the future Killer Khan), recalled that the two liked to play mahjong on Yoshimura's off days. Many years later, Baba told Masanobu Fuchi that, alongside Naoki Otsuka, Yoshimura was one of only two honest executives that he had ever worked with in puroresu. Whatever the case, though, Yoshimura relinquished neither duty. Yoshimura and Sakaguchi train at the beach, c. July 1972. After Baba & Inoki dropped the NWA International Tag Team titles to the Funks on December 7, Inoki booked it out of the Sapporo Nakajima Sports Center and checked himself into a surgery clinic for his own protection. Many were glad to be rid of him, but his absence created a new issue for Yoshimura. Inoki had been booked to challenge Dory Funk Jr. for the NWA title just two days later, and at the end of the tour, to defend the All Asia titles with Michiaki against Dory & Dick Murdoch. The following night in Osaka, Sakaguchi learned that he would be filling in for Inoki in both matches. The first was a rock-solid traveling champion’s bout. The second, in Koizumi’s estimation, was Yoshimura’s last great match, and as much a triumph on his part as his match with Karl Gotch a decade before. Years later, Murdoch gave a backhanded compliment to a man whose name he could not recall: one who, as Koizumi roughly translates, “was mostly a piece of shit, but had a lot of guts.” For the 14th and final World League, Yoshimura penciled himself to only gain eight points. That tournament, which Baba won to notch a second three-year streak, is far more notable now for what was going on behind the scenes. World Pro Wrestling ratings had plummeted to the 3% range after Inoki’s dismissal, so they forced the JWA to let them broadcast Baba’s matches. After the final, in which Baba beat Gorilla Monsoon, NTV canceled Mitsubishi Diamond Hour in retaliation, and sent feelers to Baba for a new venture. That summer, Baba announced that he would depart the company at the tour’s end. NET had insisted that Sakaguchi and Oki were not enough to sell their show on; now thanks to them, the JWA had no one else. The JWA had already booked its tour circuit for the year by the time he left, but without Baba, the promotion could only survive as long as network money funneled through. The returning Akihisa Takachiho and Gantetsu Matsuoka were given pushes, the former as Sakaguchi’s tag league partner, the latter as a challenger to fellow apple-crusher Danny Hodge. But Koizumi believes that Yoshimura was burnt out by this time. As evidence, he cites how Bobo Brazil was booked on the last tour of 1972 as Oki’s challenger for the vacant NWA International title. Oki lost the first match after a weapon attack in the second fall, as after Bobo pinned him, he rolled out of the ring and was counted out for the third. Three days later in Hiroshima, Oki struck Bobo in the throat with a foreign object. Oki had gotten a win over an icon like Bobo, but he needed a better win than that. Koizumi speculates that Brazil had already made his booking with All Japan the following February but made himself open for business under the condition that he would be protected. Yoshimura never would have accepted such a deal before, but the JWA was in a bad way, and he probably did not care much. In January 1973, Yoshimura announced his retirement. Kojika and Ushinosuke Hayashi begged Yoshimura to stay on board, but he would not be swayed. Michiaki could no longer cope with his back pain and had already arranged to move to Kobe. As he admitted in his press conference, this had been a long time coming. He had seriously considered it as far back as 1970, after the World League injury. A timeline provided in Konjo reveals that Michiaki's brother, Yoshimatsu, died in 1971; it's certainly plausible that this may have prompted some reflection. Yoshimura was too important to the company to quit after the fallout of the phantom coup, yet he had reached his limit. After one final defense on January 28, which he and Sakaguchi won against Billy Red Lyons & Mr. X (Jim Osbourne), the pair vacated the All Asia titles. Yoshimura wrestled just one more match after that. On March 3, at Kinki University’s Memorial Hall, Yoshimura defeated Ruben Juarez before Kojika & Matsuoka were set to challenge for his vacated belts. The band played his favorite song, which he had first heard during his Toyota years: the wartime ballad “Rabaul Kouta”. Yoshimura returned to Kinki’s sumo club as an advisor but quit around 1974 after losing a match to a freshman, the future Asashio Taro IV. According to Ozawa, he made his love of mahjong into his business, opening a parlor in Osaka. It has been reported that Yoshimura had some involvement in Big Japan Pro Wrestling, an organization which Yusuf Turk attempted to form in the late seventies. Outside of that, though, he stayed out of pro wrestling until the mid-nineties, when he helped out his old kohai Kojika and his own nascent BJW by introducing him to sponsors. Yoshimura got back into the business through the Rikidozan OB Association, a group of JWA alumni that promoted a few shows in the late nineties. He made a handful of appearances in this period, such as at New Japan’s 1998 Inoki the Final show. After Junzo Hasegawa’s death, Yoshimura replaced him as chairman of the Association, which held its final show in 2000. In the summer of 2001, Yoshimura served as a guest coach for his alma mater’s sumo club. That, as far as I could find, was the last notable incident of his life. On February 15, 2003, Michiaki Yoshimura died of respiratory failure. “He was a tasteful wrestler. Although he had a reputation as a technician, he was by no means a skillful person. In fact, I feel like he overcame his clumsiness with effort and perseverance to maintain his value as a technician. He wasn't very good with dropkicks, and his only footwork was an [Indian] deathlock. He didn't have a finishing hold or anything else to look at other than a rolling clutch hold. However, his guts were amazing. He also had a strong personality, going head-on and accepting any technique his opponent tried, which may have been what made him popular with Japanese fans. [...] He taught me two things: patience and fighting spirit.” - Antonio Inoki, 1990 Yoshimura and Tatsumi Fujinami at the June 30, 1996 Rikidozan Memorial Show. FOOTNOTES

-

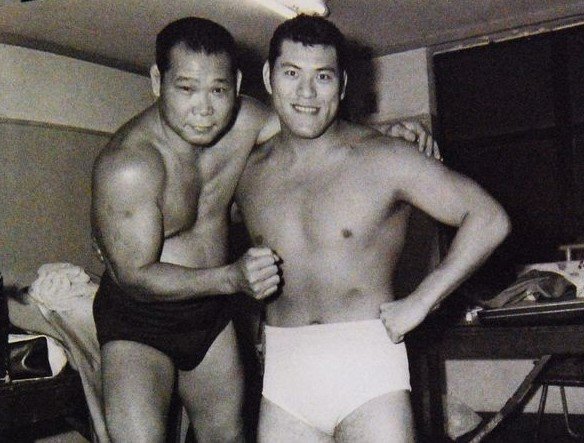

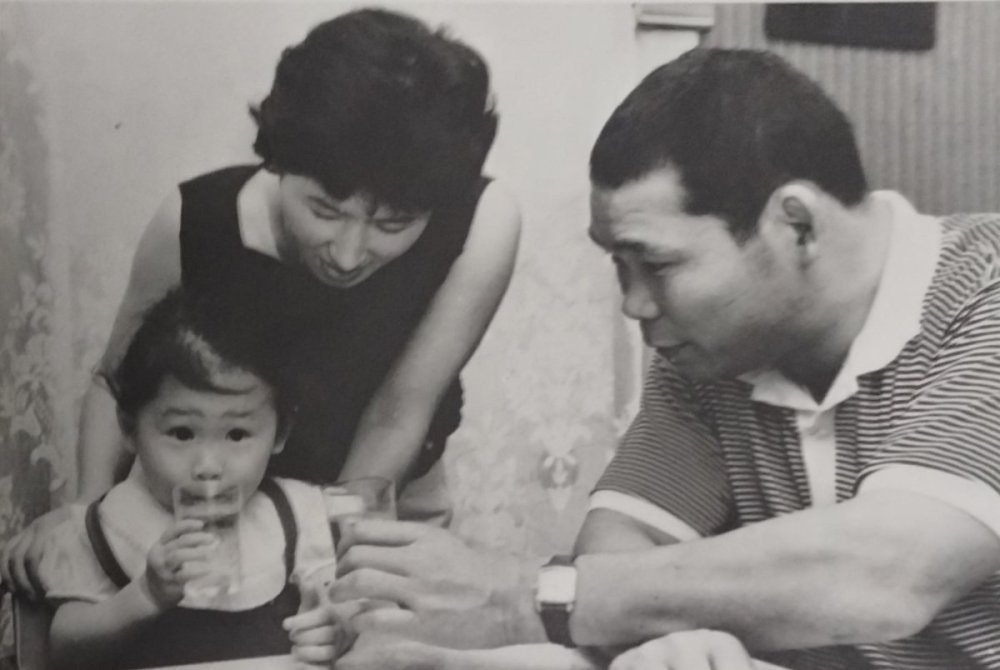

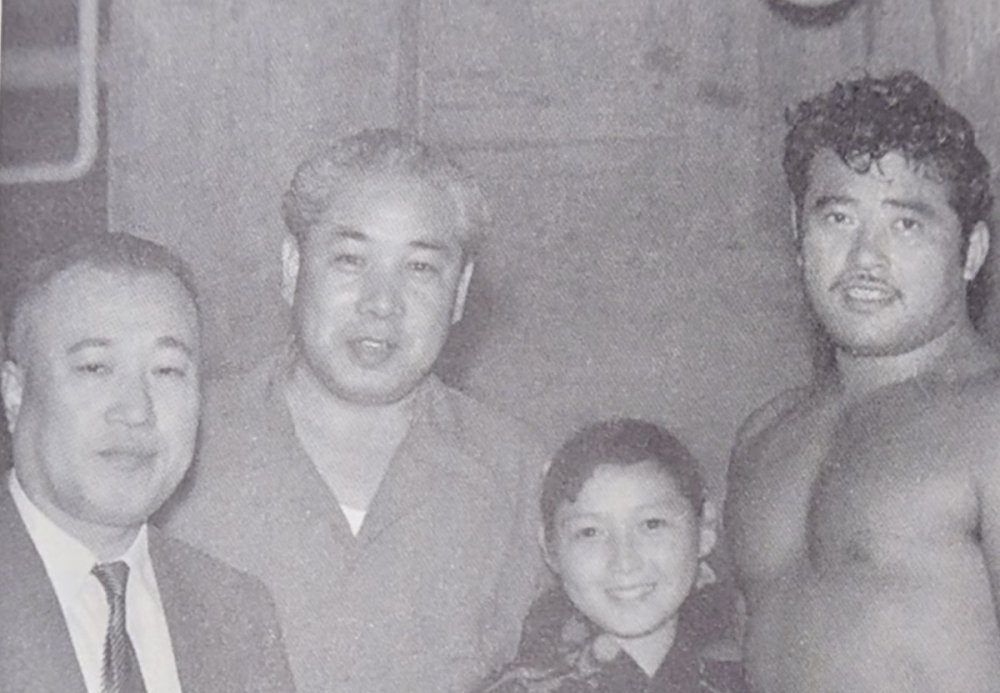

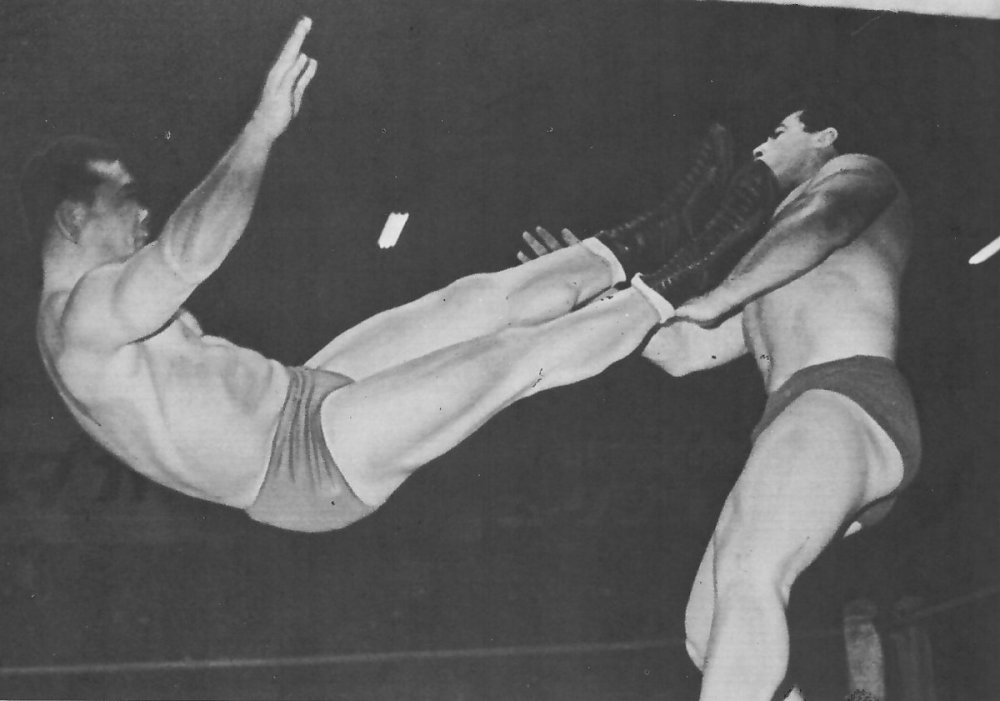

PART THREE: FIREBALL BOY (1960-1966) Yoshimura and Toyonobori spent six months working weekly Honolulu dates for Mid-Pacific Promotions. The pair returned in time for the 2nd World League. This time, Yoshimura joined Rikidozan, Toyonobori, and Endo as the fourth Japanese contestant, and as a suitable foil for former NWA junior champ Sonny Myers. The tour began with a three-night run at the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium, and Yoshimura lost both of his tournament matches on those shows, first against Dan Miller and then against Myers (see some footage of the latter here). On the third night, he and Rikidozan teamed up for the first time against Myers and tournament favorite Leo Nomellini. The first fall saw Michiaki get his win back against Myers, but the match would be remembered for the third fall, when Yoshimura took a Nomellini tackle off the apron. Selling two cracked ribs, he was counted out, then taken by stretcher to the waiting room. He missed the next show before returning to the tournament, and excluding a draw against Stan Lisowski, he won all his other World League matches. As Koizumi points out, though, just those first few matches had already shown what Yoshimura would have to offer in matches against gaikokujin. As the best worker of puroresu’s first generation, he was capable of technical matches against the second tier of a given tour’s slate of foreigners; the subsequent tour saw multiple Myers rematches, a couple of which went to 45-minute draws. On the other hand, Yoshimura was the best whipping boy to put over a tour’s top baddie and sell their killshot with a worked injury. The latter tendency earned him the nickname that provides the title for this part of the bio, “Hinotama Kozō”; the fireball was a tribute to the fierceness with which he fought whilst busted open. The next tour retained some of the World League’s foreigners for another smaller tournament, the World Selection Series. On June 2 in Osaka, the All Asia Tag Team title—which was originally a trophy—were revived after five years. The champions were set to be determined in a one-night tournament between four teams: Rikidozan & Yoshimura, Toyonobori & Endo, Myers & the Great Togo, and Dan Miller & Frank Valois. Yoshimura pinned Myers to advance to the finals against Miller & Valois. Yoshimura lost the first fall to a Valois piledriver, but evened things against Frank with a piledriver in short order. Despite the interference of Myers & Togo, the latter of whom threw salt in Yoshimura’s eye, the match result stood as Yoshimura’s loss by countout. Rikidozan successfully appealed to the commissioner to keep the title vacant until a match five days later in Nagoya. There, though, Rikidozan teamed up with Toyonobori, and the pair won the titles. Yoshimura would fill in for Toyonobori on subsequent occasions over the next few years, and although it is commonly presumed that Toyonobori’s supposed injuries were fictitious coverups for his disappearing acts to evade debt collectors, it was he who remained favored by Rikidozan. Yoshimura never totally shook off his status as an outsider. On August 19 at Tokyo’s Taito Ward Gymnasium, the Japan Junior Heavyweight title was thawed for a final defense to mark Yoshimura’s promotion to the heavyweight division. If one excludes TV tapings, this was the first singles main event of Yoshimura’s career. In a match refereed by his boss, Michiaki went the full 61-minute Hawaiian Broadway with Yoshinosato. The champion struck first with a headscissors, and a lively exchange followed for the first five minutes. Yoshinosato was physically inferior, but he was scrappy, and he wore Michiaki down with fouls as the match progressed. Yoshimura won the first fall in 28 minutes with a half crab, but the challenger got a pinfall in 37:35. Yoshimura’s second wind petered out in the last ten minutes, and the grueling match went to a draw. Yoshimura, Sachiko, and their daughter Kiyoko in the early sixties. Yoshimura left for a second Hawaiian excursion in December, by promoter’s demand. Sadly, he missed the birth of his daughter the following month. On January 11, he took part in a one-night tournament for the number-one contendership to the Hawaii Heavyweight title, and beat Lou Newmann in the quarterfinal, but then lost to former NWA world champion Dick Hutton. Hutton went to a draw in the final against Sam Steamboat, after which the contender was decided by a coin flip. Hutton beat Al Lolotai to win the title on January 18, only for Steamboat to beat him to begin a four-month reign. Yoshimura claimed in Konjo that Hutton made a great impression on him, and that he had personally requested a match with him to promoter Al Karasick. During this excursion, he finally mastered a move that he had previously seen from Lord Blears, and which he claimed Blears encouraged him to adopt. That move came to be known in Japan as the rolling (back) clutch hold, or kaitenebigatame, but you know it as the sunset flip. On February 1, Yoshimura got a title shot against Steamboat and went to a 45-minute draw; according to him, the one fall he scored was with the rolling clutch. Koizumi also believes that Yoshimura could have been inspired by seeing Eduoard Carpentier work in Hawaii. He returned to Japan at the end of April, to meet his daughter Kiyoko and to enter the 3rd World League. The tour kicked off on the first of the month, with the most famous match of Yoshimura’s career. “And then the first match I had was in Tokyo Palace. I saw the guy. He was a college sumo champion and he was pretty good worker, too. We worked there. But the way I worked over there was they asked me. They said, "Can you go through with him?" I said, "Sure. Why not?" Because he thought nothing of me. He thought I was a small guy. So, by the time the match was over, I got a standing ovation. They never saw that before in Japan.” - Karl Gotch in conversation with Jake Shannon, October 2004 Karl Krauser, the man who would be Gotch, was an Olympian wrestler with a decade in the business, and a background in catch-as-catch-can through the training of Billy Riley. Unlike the first two iterations of the tournament, in which all but the final match were contested in three eight-minute rounds, this year’s matches were three-fall, 45-minute affairs, and the pair used all of that canvas. Krauser won the first fall with the first German suplex ever performed in a Japanese ring, and Yoshimura won his own fall with a backslide, before the two went to a stalemate. Koizumi believes that this is one of the most important matches in puroresu history, and one sees his point. For his part, Yoshimura called it the best match of his career, and considered it a personal breakthrough. Even in its cruelly abbreviated form, this match is one of the most valuable pieces of wrestling footage in the 1960s. In a display of his versatility, Yoshimura put over Jim Wright the following night in a bloody brawl. He wrestled Krauser four more times on this and the subsequent tour. First, Karl won a League rematch on May 13. On July 2, Yoshimura forfeited the third round of an Ibaraki outdoor show, but the match was deemed a no-contest at Krauser’s request. Finally, at an elementary school in Fujiyoshida on July 22, Yoshimura won a 2/3-falls match. It was the only time that Gotch lost two falls clean to a Japanese wrestler. Another draw followed in Sawara two days later. Yoshimura wrestles Kanji Inoki in August 1962. 1961 also saw Yoshimura try on a new hat. According to Dave Meltzer’s obituary, Rikidozan regarded a match with Michiaki as the ultimate aptitude test for a young wrestler. That June, Shohei Baba’s last match before leaving for the States was a loss to Yoshimura. In July, Kintaro Oki stepped up to face him in Asahikawa. Finally, on May 13, 1962, Kanji Inoki suffered his first loss to Yoshimura. From that first Baba match through the end of 1963, the “three crows” of the Riki Dojo wrestled a total of over fifty singles matches with Yoshimura. As each man grew in experience, their matches were occasionally expanded to 2/3 falls, and even given the semi-main time limit of 45 minutes. Mammoth Suzuki, Mitsuaki Hirai, Umanosuke Ueda, and Gantetsu Matsuoka also had singles matches with Yoshimura in this period. Two weeks after the Riki Sports Palace opened, the JWA held their first show at the Roppongi venue on August 13. In the main event, Yoshimura teamed up with Rikidozan and Toyonobori to face the Zebra Kid, Aldo Bogni, and Don Manoukian. Bloodied in a foul that ended the first fall, his wound was exploited by the Zebra Kid’s assault, and by the third fall, Yoshimura was unable to continue. Oki Shikina overturned the match as a DQ win for the natives, while Yoshimura begged for a chance to get even. The JWA’s next scheduled main event was Riki & Toyonobori vs. Zebra & Manoukian, and after Toyonobori was written out with a supposed wrist injury, Endo was initially penciled in as his replacement. Yoshimura filled in for Endo as Riki’s partner and got that shot against Zebra & Manoukian. Zebra busted him open with a wooden chair from the press box, and was put down for the first pinfall by a bodyslam and tackle. The heels booked it out of the arena in the second fall, to escape their comeuppance from a furious Rikidozan. Mitsubishi Diamond Hour expanded to a weekly program. It still alternated the 8:00pm timeslot with Disneyland, but aired at 10 on those weeks. At a TV taping in December, Yoshimura put over Luther Lindsay in a big way, selling his backdrop at 7:29 as a concussion-inducing knockout, and allowing Luther to win two falls with one move. In 1962’s 4th World League, which reverted to the original three-round system, Yoshimura wrestled the likes of Lou Thesz and Freddie Blassie. He also received three matches with Dick Hutton, and while he lost the League match, he won their last encounter, which took place on Hutton’s last date. Koizumi speculates that the former NWA champion put Yoshimura over as a gesture of respect. In 2018, fellow entrant Larry Hennig told Koji Miyamoto that Yoshimura had impressed him most among the Japanese. At the start of the autumn tour, Rikidozan had suffered a legitimate shoulder injury against Moose Cholak but was forced by show promoters to return to the ring after just four days. He got through by borrowing his son Yoshihiro’s football pads, and the tour became a waiting game for when he would remove them. Just days before a scheduled tag defense, Toyonobori injured his leg on a house show in Hakodate; as he was present for the defense in question, this injury was apparently legitimate. As the story went, commissioner Raisuke Kudo persuaded the challengers over beer and a grilled mutton hot pot to accept a match with Yoshimura as a substitution. Unbeknownst to Murphy and Marconi, Riki had healed, and when Murphy made a crack about whether Riki was looking to play football, the ace threw the pads into the crowd. Murphy bloodied Yoshimura with an empty can in the first fall, which the natives won by DQ when Cholak and Art Mahalik interfered, but Skull took a Yoshimura pin for the second fall. In early 1963, Toyonobori disappeared again for a supposed knee injury. Kudo offered to have Yoshimura substitute for Toyo again on the January 29 defense against Jess Ortega and Tony Marino. This time, Riki instead opted to vacate the tag titles first. In this match, as well as a March 4 rematch, the Japanese team won, but did not score two falls either time, so the belts were held up until Toyo returned in May. In the 5th World League, the first with an equal slate of Japanese contestants (if you count Rikidozan, who did not wrestle in the League seed itself), Yoshimura got one clean win against Sandor Szabo, and half-points for countouts and fouls against Fred Atkins, Bob Ellis, and Gino Marella. This tour is more remarkable for Yoshimura in that there is surviving footage of four matches from this tour: tournament matches against Pat O’Connor and Killer Kowalski, and a pair of tag matches. On the last day of May, Yoshimura beat the future Gorilla Monsoon in the main event of a televised benefit show for the Tokyo Olympics. At some point during the year, Yoshimura also invited former AJPWA coworker Kanji Higuchi, who had retired from the JWA in 1960, to return in a backstage capacity and look after gaikokujin.1 On November 22, 1963—incidentally, the date of JFK’s assassination—Yoshimura was taken out by Rikidozan’s own chop. This is notable because, while such friendly-fire finishes would continue to show up in the JWA, they never happened on the native side. Two weeks later, Yoshimura teamed up with Rikidozan on the last show of the tour, in a six-man tag in Hamamatsu which went to a full broadway. The following night, his boss was stabbed in a nightclub. Before Rikidozan’s public funeral on December 20, a private wake was held at his penthouse. From what I gather, it was there that the regime changes began. Alongside Toyonobori, Yoshinosato, and Endo, Yoshimura was promoted to a director. As an executive, his primary responsibilities were as a booker and as the collector of payments from promoters. In order to adequately cover what happened next, I have to cover the further upheaval. On January 7, 1964, politician Wataru Narahashi stepped down as president of the JWA’s shareholders’ association.2 He was replaced by ultranationalist fixer Yoshio Kodama, as Yamaguchigumi godfather Kazuo Taoka took a vice chairman position, and Toseikai leaders Hisayuki Machii and Fujimatsu Hirano were named as auditors. These men had indirectly had a hand in the JWA for years. All its events west of Lake Biwa were promoted by Taoka’s Kobe Entertainment company, while Kodama ally Goichi Okamura ran northern shows, and the (mostly Korean) Toseikai had taken over promoting Tokyo shows from the rival Sumiyoshi gang.3 This is without getting into Rikidozan’s association with Kodama and Machii with regard to their political dealings with South Korea [see my thread on Kintaro Oki and early Korean wrestling for more]. Finally, on January 10, widow Keiko Momota assumed a figurehead position as JWA president, which was crucial to keeping the Mitsubishi sponsorship and the NTV show. Unbeknownst to her, the wrestler-executives soon surreptitiously founded a company with a nearly identical name to funnel JWA funds away from the main Kogyo, and by extension, the debt-ridden Riki Enterprises which now shackled Keiko. Yoshimura and Baba, the future double tag champs, team up in May 1964. On February 20, Yoshimura teamed up with Toyonobori to challenge Prince Iaukea & Don Manoukian for the vacant All Asia title. Toyo lost the first fall to Iaukea’s diving body splash, but lured and dodged a second splash to pin the future King Curtis. Bloodied yet again, this time with wire-wrapped fists, Yoshimura hit a series of dropkicks on Manoukian to get the pinfall, and to finally win the titles. For a very brief time, Yoshimura was the #2 star in the company; but it was a very brief time. Nippon Television wanted to build around Giant Baba, as they loved what they had seen in his six-month return to Japan the previous year. On the 6th World League tour, Yoshimura placed third among the Japanese, with all between him and the returning Baba being a loss, and not a draw, to Gene Kiniski. On May 9, Toyo and Yoshimura defended the All Asia title against Kiniski and Caripus Hurricane, but three days later, they lost the belts to the same team as Yoshimura sold a rib injury. Naturally, this set up the debut of the Toyo-Baba team, which won the titles back on the 29th. That same day, commissioner Bamboku Ono died in Shinjuku. One could credibly argue that this was almost a severe a blow to the JWA as Rikidozan’s death had been, as the flagrantly yakuza-friendly Ono had provided a buffer between the company and law enforcement. The day after Rikidozan’s funeral, Kodama had formed the Kantokai, a coalition of seven gangs. (Four of which were those involved with the JWA.) Shortly before the new year, the Kantokai issued a pamphlet which urged the Liberal Democratic Party to “immediately” settle its internal strife. It was the first time that yakuza had shown solidarity to influence national politics. An outline of prevention measures had been approved in 1961, born out of the need to tighten security before the Tokyo Olympics, but gang violence had persisted. The Kantokai finally prompted the Tokyo Metropolitan Police to begin the first major yakuza crackdown, the First Summit Operation. With Ono now out of the picture, they were clear to begin in earnest. After the summer tour, Toyo and Yoshimura left for Hawaii as the JWA held TV tapings at the Palace to showcase Baba. These were Yoshimura’s final matches in the territory, the last of which was against summer tour booking Nick Bockwinkel. When he returned, the Tokyo Olympics had begun. Competing with that was a fool’s errand, so the JWA only held a couple shows before the Games concluded on October 24. Meanwhile, as prime minister Eisaku Sato took office, the Summit really got rolling. The JWA were a primary target, as they were a primary source of funds for several important gangs. The Ministry of Home Affairs pressured local governments not to rent out public facilities, the “gymnasiums and cultural centers” which were the backbone of a tour circuit, to gang-related entertainments such as JWA shows and concerts.4 After the Destroyer had defended the WWA Heavyweight title against Toyonobori in April, which had drawn a 51.4 TV rating, he returned for four shows in early December, where he put over Toyonobori and dropped the WWA heavyweight title. The first of these matches, in Osaka on the 1st, is the only one in circulation, and the only case of Yoshimura’s killshot sells that survives. Thirty-five minutes into a six-man tag, the Destroyer kips himself out of his rolling body-scissors and puts in the figure-four leg lock. It wins him two falls in one. When the JWA finally booked him for a full tour, 1965’s Golden Series, Yoshimura worked in over half of the Destroyer’s 39 matches. Dick Beyer held Yoshimura in very high esteem. In 2002, he told Yusuf Turk that he had been the best Japanese wrestler.5 On February 18, 1965, Kobe’s Oji City Gymnasium rejected an application for a JWA show, after police investigations revealed Taoka’s involvement in previous shows at the venue. Four days after the Kobe show was turned down, Taoka, Machii, and Hirano officially resigned from their positions in the Association as their terms expired. (It is often erroneously reported that Kodama resigned alongside them, but he actually stayed on board until February 4, 1966, when he was replaced by Yoshikazu Hirai.) On the 26th, Toyonobori defended the WWA title in Tokyo against the Destroyer. 1,300 Toseikai came to the show, and police were posted to meet them. Keiko Momota and sales manager Hiroshi Iwata resigned in March. In the new regime, Toyonobori became president, Yoshinosato became vice president, and Yoshimura became “executive managing director” of the kogyo. With all this muck surrounding the JWA, Yoshimura’s ground-level role in show management meant that it fell to him to convince local venues that the JWA had cleaned itself up. It was a severe blow to their sales. As wrestler Matty Suzuki recalled in Vol. 12 of Japan Pro Wrestling Case History (2015), what he had seen in the company’s dealings with Kobe Entertainment were, by and large, legitimate and efficient salesmen. Nevertheless, a 1979 article in Monthly Pro Wrestling reports that the police forced the JWA to cut ties with all but seven of the promoters that they had sold shows to. Around two-thirds of the JWA’s events had been sold shows, but as the company struggled to find new promoters, it was forced to organize more of its events in-house. Personnel such as wrestler Isao Yoshiwara and announcer Toshio Komatsu transferred into sales, and both of them were gone by 1967. It was a turbulent period, and some of that laid on Yoshimura’s fellow wrestler-executives. Endo took advantage of the company’s sloppy accounting to line his pockets, while Toyo regarded the company vault as his horse-betting fund. After Toyo and Baba lost the tag titles to the Destroyer and brother-in-law Billy Red Lyons, Yoshimura filled in for the president in a June 22 rematch, a draw which headlined the first wrestling show at Nagoya’s Miyagi Sports Center. It just so happened that this show had taken place on the very day that Japan and South Korea signed the Basic Relations Treaty, and Hisayuki Machii had organized a celebration party. Machii may have stepped down from the Association, but Toyo was still obligated to attend this party, not least to get to Machii’s patron. Kintaro Oki had been expelled from the JWA shortly before, but with South Korea now open for business, he cut a deal to set up shop there with a JWA partnership. That August, Yoshimura was one of four JWA wrestlers who worked on Kim Il’s first Korean tour. Yoshimura, Baba, Yoshinosato, and Toyonobori in an ad for Guinness beer, circa November 1965. That autumn, NTV’s plan to push Baba as the JWA’s ace finally blossomed. Toyo’s disinclination to defend the WWA title on US soil had strained the JWA’s relationship with its American ally. So, in Osaka on November 24, it was Baba who beat Dick the Bruiser to win the new, WWA-certified International Heavyweight title. Toyo’s last match in the JWA was on the December 17 Palace taping, billed as the third anniversary Rikidozan memorial show. He teamed up with Yoshimura against Johnny Kostas and Stan Pulaski. Four days later, the president was conspicuous in his absence from a Meiji Shrine photo session. Toyo resigned from the company under the cover story of ureteral stones. In truth, he was dismissed for the 30 million yen he had misappropriated. PR head Yasuaki Oshiyama denied to the press that anything had happened, but rumors soon swirled. Toyo’s resignation, and a new regime, were announced on January 5, 1966. Yoshimura was an outsider, and Endo was too unpopular, so Junzo Yoshinosato became president Junzo Hasegawa. Around this time, head referee Oki Shikina was arrested for firearm possession. When Yoshimura recalled that his old AJPWA buddy had doubled as a referee there, Joe Higuchi found his true calling. February saw Baba beat Lou Thesz, but it also saw the announcement of Toyonobori’s new venture, Tokyo Pro Wrestling. The JWA was concerned that Toyo would try to swipe Antonio Inoki, who had been working overseas for two years. When Inoki spoke with Mr. Moto in Los Angeles, he was informed that he was booked for the 8th World League, like a foreigner; that is, he was not booked to return to Japan. He was bothered by this treatment, and asked Kintaro Oki about the matter, but was told to ask Yoshimura about it. On March 13, Yoshimura flew to Hawaii to meet Inoki, Oki, and Baba. Inoki did not get a satisfying discussion out of Yoshimura, and as he later recalled, the executive thought that Inoki was just concerned about pay. On the 16th, Yoshimura received a call from Inoki. He claimed he had urgent business to attend to, and would return to Tokyo the next day. Five days later, Inoki called the JWA office to notify them that he wouldn’t be coming back to them. It was then that the JWA knew Toyo had struck, and they made the true circumstances of his dismissal known. Decades after the JWA’s demise, Yoshimura conceded that he should have pushed Inoki more than he did. As he admitted, though, he never fully trusted him again after Hawaii. The 8th World League was a troubled tour. On top of Inoki’s cancellation, early marketing had centered around top foreigners Bill Watts and Jake (Grizzly) Smith. When both of them canceled at the last minute, their replacements—Pedro Morales and Wilbur Snyder—may have been bigger names, but the suddenness of their substitution damaged early attendance. The nadir was a show on April 10 that was canceled midway through its opening match, as just seven hundred fans sat in the 6,000-seat arena. As for the tournament itself, this was the first World League to adopt a consistent structure, a round-robin between native and foreign teams. Yoshimura booked himself to place third among the natives, behind Baba and Kim Il (Oki), with losses to the aforementioned top stars. On April 27, Baba and Yoshimura fought Morales & Snyder for the vacant All Asia title in the Fuse City Gymnasium, near Kinki University. The cheer squad showed their support for their alumnus, but Yoshimura gave up the first fall to Morales. Baba may have gotten the second fall, but just as he had Morales bloodied and sprawled out for the winning pin, the bell rang. The titles remained held up. Four days after Baba won his first of six World Leagues, a small transitional tour began before Matsuda’s arrival marked the start of the Golden Series. This tour was headlined by Killer Karl Kox, who had gained some notice through press coverage of his Dallas matches against Inoki, but was undoubtedly on a lower rung than the previous tour’s stars. On a televised buildup tag to his All Asia title match, alongside LA Rams defensive tackle Joe Carollo, Kox performed his signature brainbuster on Yoshimura, who sold a concussion and did a stretcher job. Not two weeks later, Karl beat Baba by countout in a non-title match when he hit a brainbuster on the floor. Thanks to Yoshimura’s booking, Kox left Japan a star. In one of puroresu’s great nomenclative quirks, his “brainbuster” soon became the catchall term for a vertical suplex, with the proper maneuver classified as a “brainbuster drop”. On May 23, the pair beat Baba & Yoshimura in Sendai, with Kox putting Baba down himself to win the final fall. Whoever won the titles was set to defend them at the start of the next tour against Hiro Matsuda & Duke Keomuka in Sapporo, but in kayfabe, Yoshimura “begged” Keomuka to step aside and let him work with Matsuda. Hiro had returned to Japan in the winter of 1964-5 to hold a seminar at the JWA dojo, but had not wrestled back home since leaving the JWA as a trainee. From the looks of it, he had been booked to prevent him from shacking up with Tokyo Pro and his former partner Inoki. Hiro Matsuda suplexes Sam Steamboat in Kawasaki. Matsuda & Yoshimura won the All Asia title on May 28, taking two straight falls from Carollo. On June 18 at the Kawasaki Baseball Stadium, the champions wrestled Eddie Graham & Sam Steamboat to a time-limit draw in one of the most famous Japanese matches of the period. Nine days later, Kox & Graham joined forces to beat them before Baba & Yoshimura reconvened and won them back on the first of July. The belts may have gone back to the #1 and #2 stars of the company, but Yoshimura’s run with Matsuda was a glimpse of the purpose that the All Asia title, and his supporting role as co-champion, would later serve. Remaining in Japan after the tour’s end, Matsuda himself booked Karl Gotch for his first JWA tour in five years. To Karl’s chagrin, his scheduled match against Baba was booked as a non-title match.6 He would not even make it that far, as a bout with cellulitis in his right leg led Gotch to cancel. Before that, though, Gotch got a rematch with Yoshimura on July 29, and their 45-minute draw at the Palace drew a 33.9% TV rating. Mike Paidousis & Fritz von Goering came to Japan with a pair of WWA-certified tag titles, which they first defended against Baba & Yoshimura. In a standard 2/3-falls match, it took 52 minutes for Paidousis to get a fall on Yoshimura. The match drew jeers and heckles from the Osaka crowd. With Tokyo Pro’s first tour on the horizon, it was a bad look for the company. Baba & Yoshimura defended their own titles against likely the heaviest team that Yoshimura ever worked against, Gorilla Monsoon & Man Mountain Cannon. The tour culminated in a double tag title match at the Kuramae Kokugikan, which the native team won clean, 2-0, in just over twenty minutes. Baba & Yoshimura vacated the All Asia trophies, as the International Tag Team championship became the JWA’s primary tag titles, and the trophies themselves were relegated to use as a prop in postmatch photos backstage. The last tour of 1966 was marked by the JWA’s bold decision to book the Nippon Budokan for the first time, in response to Tokyo Pro’s kickoff show at Kuramae that October. It was also marked by the mid-tour debut of Fritz von Erich, after negotiations which had begun in conjunction with the Budokan booking. The busy wrestler-promoter was only available for a week, and with the schedule they had planned, the JWA only had four shows to establish Fritz before the Budokan show. They managed just fine, with a heated warmup title match in Osaka that may have ended in bullshit circumstances (Baba’s friend Gorilla Monsoon pulled Fritz out to force a countout), but still got Fritz over through its brutality. The Budokan card was a one-match show, but the semi-main was notable in its own right. Before Baba and Fritz’s classic rematch, Yoshimura teamed up with Kintaro Oki, who had been brought back under his original ring name the previous tour, to challenge Eddie Morrow and Tarzan Zorro for the vacant All Asia titles. A proper pair of belts had finally been commissioned through Yoshinaga Prince, a manufacturer best known for their lighters. One has to wonder if the belts were made because of Oki, to allow the titles to be more easily transported to Korea. Because, sure enough, he and Yoshimura won. Yoshimura went to Seoul for the holidays. On Christmas Day, he and Oki defended their titles at the Jangchung Gymnasium against Morrow & Zorro. FOOTNOTES

-

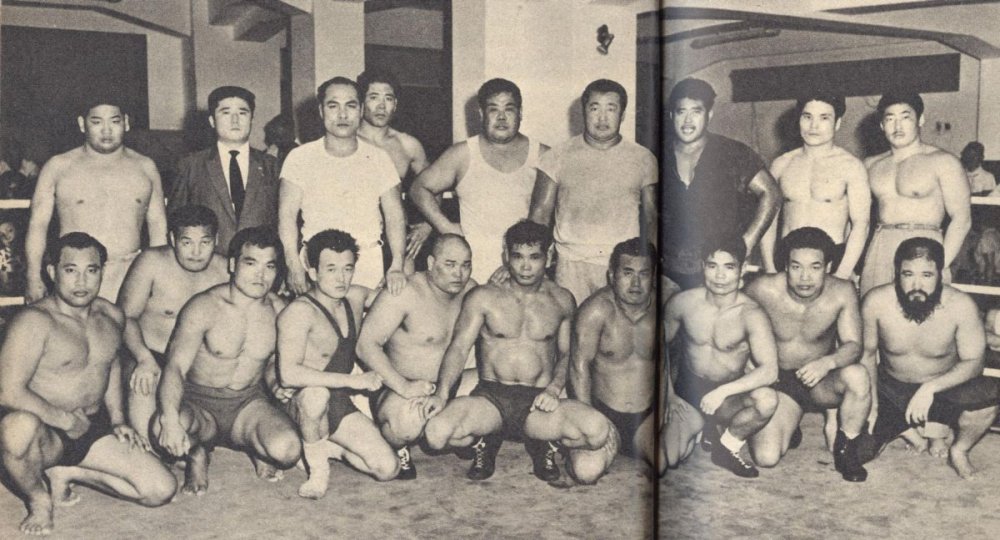

PART TWO: THE JUNIOR YEARS (1954-1959) On July 18, 1953, a benefit show for Kitakyushu flood victims was held at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium and headlined by a judo vs. sumo match. In one corner was Toshio Yamaguchi, an alumnus of the International Judo Association who had entered American pro wrestling alongside Masahiko Kimura. In the other was Umeyuki Kiyomigawa, a retired rikishi who had recently returned to his sport through the Otani Heavy Industries sumo club. This show was but part of the Kansai region’s juken [judo vs. boxing] revival, spearheaded by future joshi promoters Touichi Mannen and Morie Nakamura, but it was this show that led to the birth of Kansai’s early puroresu scene. A GI read an article on the show and pitched a match with wrestler Bulldog Butcher—his commanding officer—to Yamaguchi, and this rejected proposal reached the ears of local yakuza boss Shojiro Matsuyama. Matsuyama approached the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper with intent to promote a show, and the All Japan Pro Wrestling Association was born, mere weeks after the formation of the JWA. (Newspapers were crucial for promoting such events in postwar Japan, due to the quotas of American cash they received.) In fact, the AJPWA preempted the latter organization with a two-night run at the Prefectural Gymnasium that December. Two months later, Yamaguchi, Kiyomigawa, and fellow Otani sumo alumnus Hideyuki Nagasawa took part in the JWA’s first tour; before that, though, the AJPW ran the OPG again on February 6 and 7, and the first show received a regional NHK broadcast. That April, the AJPWA began its first full tour, billed as a twelve-show tournament pitting Japan against US forces. In Konjo, Yoshimura gives two contradictory accounts of the circumstances in which he joined the AJPWA, the first of which ends the section about his collegiate sumo days, and the second of which begins the coverage of his pro-wrestling career. In both accounts, he claims that he traveled to Osaka on his Golden Week holiday alongside corporate sumo buddy Jiro Yamazaki, and in both, he states that he encountered the Association on May 1. In the second account, he claims that he came backstage for a show at the OPG, which even the paucity of records make clear could not have taken place. Therefore, if I believe either account, I am inclined to believe the first, in which Yoshimura claims that he instead visited the company’s office in the Namba district. According to this version, Mainichi reported that he had joined the promotion the following day. Unlike the JWA, whose shows are fairly well documented until the period of decline in 1957, the AJPWA suffers from incomplete records. In Konjo, Yoshimura states that he debuted on a Kobe show in August, where he wrestled former IJA judoka Noburo Ichikawa to a fifteen-minute draw. On September 25th, he wrestled on the first documented Association show after the opening tour, which took place at Osaka’s Ogimachi Pool. He won by foul against Jim Gretsch in puroresu’s first show in water. This show received another regional broadcast, and as Yoshimura wrestled the fifth of seven matches, it is probable that his match was televised. On January 28, 1955, the JWA and AJPWA squared off in a Tokyo show. Rikidozan and Yamaguchi wrestled in the last challenge that the former would ever accept from a Japanese wrestler. According to The Face of the Box Office, a 2004 biography of impresario Sadao Nagata (more on him later), both men were eager not to risk a repeat of the previous month’s infamous Rikidozan/Kimura match, which could have dampened the pro wrestling boom. That is not to say that match made Yamaguchi look good, as he was working with a fractured rib and lost by countout. In fact, the only Association member that came out of that show looking good was Yoshimura, who won his undercard match against Yonetaro Tanaka.1 The AJPWA tried to bounce back that March with three-night stints at the OPG and Tokyo’s Kuramae Kokugikan. One of the Association’s most influential supporters, the Yamaguchigumi godfather Kazuo Taoka, had failed to leverage his friendship with Nagata to get Rikidozan to appear as a referee. As these shows bombed, Taoka left Matsuyama in the lurch. Kiyomigawa left the Association that autumn to join Masahiko Kimura’s Kokusai Pro Wrestling as it expanded from its Kyushu base. Yoshimura claimed that he rejected an offer to join the JWA when they ran the OPG in November 1955. The AJPWA started 1956 with a final five-day run of shows there, after which they lost the support of Matsuyama.2 The Osaka market was crowded by Kimura’s Kokusai as well as Toa Pro Wrestling, a promotion headed by Zainichi Korean Matimichi Daidozan. The AJPWA’s Kenji Tamura and Hisaharu Kaji made an extremely unusual transfer from puroresu into sumo, while others remained in Osaka until the summer, when they left with Yamaguchi to his hometown of Mishima. Etsuji Koizumi writes that they ran shows as Yamaguchi Dojo. There are no records of Yamaguchi shows until autumn 1957, though, and testimonials from the time are bleak. Kanji Higuchi had eaten three meals a day in Osaka, but in Mishima, he lived off of udon noodles cooked in an aluminum basin with seawater broth. Yuichi Deguchi even returned to Osaka to beg future AJW promoter Takashi Matsunaga for a spot on a juken show where Matsunaga fought as a fake Thai boxer. Yoshimura does not confirm in Konjo whether he went to Mishima too, but he recalled that he had lost the desire to wrestle in Osaka, due to the constant power struggles and intrigue. That autumn, Yoshimura was invited by commissioner Raisuke Kudo to compete in the JWA’s Japan Weight Class Tournament. This had been in the works for a while. By the time it happened, though, the AJPWA had fallen, and after Kimura and Kiyomigawa had left for Mexico in the summer, Kokusai splintered into Asia Pro Wrestling and the Hokkaido-based New Japan Pro Wrestling. There were three tournaments: light, junior, and heavyweight. The stated purpose was to determine a new heavyweight challenger for Rikidozan, but the true aim of the tour was to delegitimize the JWA’s competitors and scout talent worth poaching. Yoshimura entered under the Yamaguchi Dojo name because, as he claimed, the commission would not have allowed him to compete as a freelancer. The tournament began in somewhat infamous fashion on October 15, in a show at the Japan Pro Wrestling Center open only to the commission and the press. There were multiple shoot incidents throughout the preliminary show, which held the first two rounds of the light heavyweight bracket and the first round of the junior heavyweight. Yoshimura’s friend Jiro Yamazaki lost to top JWA junior Surugaumi after a 25-minute bout. Michiaki’s own first opponent was Asia Pro’s Hiroaki Kato, a fellow Gifu native and judoka with experience in corporate sumo. In just under five minutes, Michiaki won with a hip toss and an arm lock. He had made it to the final four, alongside Surugaumi, the JWA’s Osamu Abe, and Toa’s Daidozan. On October 23 and 24, the JWA continued the tournaments with a pair of shows at the Ryugoku International Stadium. Yoshimura squared off against Daidozan on the first night. The Korean judoka had squashed Yonetaro Tanaka in his qualifying match, grabbing an armbar in less than a minute. This semifinal was more competitive for both men. Yoshimura took several throws while targeting Daidozan’s legs, but when he got him in the half crab, Daidozan would not give up. After a pair of dropkicks, Yoshimura got the submission with a neck hold in 12:55. Yoshimura and Surugaumi fought numerous times in the year to come. On the second night, Yoshimura faced Surugaumi for the Japanese Junior Heavyweight title. Yoshimura got out of an armlock by tripping his opponent, and applied a full nelson after a snapmare, winning the first fall by submission in 15:38. Surugaumi came back to the armlock in the second fall, although Konjo’s claim that this was how he won it is contradicted by official records, which give the result as a Surugaumi half crab in 3:46. Both accounts concur on the result of the final fall, where the JWA original won with an “inverted body scissors” in 5:12. Six days later, Yoshimura returned to Osaka. According to the AJPWA’s Japanese Wikipedia page, this show was billed as an AJPWA event for its 90-minute regional broadcast. Yoshimura put over Toyonobori in the third-to-last match. Then, Surugaumi made his first defense against Yoshinosato, and the two went to a 45-minute draw. Finally, Azumafuji and Yamaguchi squared off in a rematch. On the 24th, the two had gone to a double countout. This time, with Riki as referee, Azumafuji went over. The JWA returned to the OPG for a pair of shows on January 4 and 5, 1957 and on the first of those, Yoshimura got a rematch. After losing to a half crab in the first fall, Yoshimura got a pinfall on Surugaumi in the second. However, Surugaumi hurt his ankle in the third fall, and the title did not change hands by forfeit. Konjo kayfabes what came next as the result of pleading Rikidozan for one last shot. That last shot came on April 8, in an Osaka show billed as the “Pro-Wrestling Japan Championship Tournament” and featuring more JWA vs. Asia Pro/Toa matches. This time, he avoided the dreaded arm-scissors for as long as possible. Surugaumi almost got it after a bodyslam, but Yoshimura twisted to get him off. Sensing opportunity after a headscissors and attack, a hard dropkick brought Surugaumi down for the first fall. Yoshimura knew that if he tried that again in the second fall, Surugaumi would get out of the way and go for the body-scissors like he did in the 1956 Osaka match. So, he got him with his own arm-scissors and rolled him across the mat until Surugaumi gave up. As he claims, Yoshimura won 2-0. The JWA roster poses at the Japan Pro Wrestling Center, circa 1957. Clockwise from top left: Seishiro Yoshidagawa, unknown (possibly announcer Naoyoshi Akutsu), Kanji Higuchi, Surugaumi, Azumafuji, Rikidozan, Kokichi Endo, Tomio Miyajima, Takao Kaneko, Osamu Abe, Junzo Yoshinosato, Kiyotaka Otsubo, Hideyuki Nagasawa, Michiaki Yoshimura, Masaaki Takemura, Isao Yoshiwara, Tamanokawa, Yonetaro Tanaka, and Matimichi Daidozan. Alongside former AJPWA wrestlers Yuichi Deguchi, Kanji Higuchi, and Hideyuki Nagasawa, Asia Pro’s Kiyotaka Otsubo, and Toa Pro’s Daidozan,3 Yoshimura was brought into the JWA. According to The Face of the Box Office, though, Yoshimura came at a price. Rikidozan was forced to pay some three million yen to the Kansai yakuza bosses which had made up the AJPWA’s board of directors. In an era when a wrestler’s salary started at ten thousand a month, that was an exorbitant (indeed, extortionate) amount. On June 15, the JWA premiered its first weekly television program. Puroresu Fighting Man Hour was taped at the Nihonbashi dojo every Saturday at 5:00PM. Yoshimura defended his title against Surugaumi, Yoshinosato, and Daidozan, while Yoshinosato and Kokichi Endo won and then twice defended an All Japan Tag Team title that was likely just created for marketing. In the last of PFMH’s first eight episodes, after which the program was put on hold as the JWA went on a summer tour, Yoshimura and Surugaumi got a title shot together. By this time, the program was sponsored by Mitsubishi Electric. While he kept a constant presence as a commentator and referee, Rikidozan rarely wrestled on the program, and when he did, it was usually in a low-stakes exhibition tag. Koizumi does not know for certain whether Rikidozan watched Wrestling from Marigold on TV during his time in San Francisco, but he speculates that Rikidozan’s plan was to replicate “the Chicago model” of the early fifties, where Fred Kohler had promoted Verne Gagne as his ace on the popular Dumont Network program while saving Lou Thesz’s NWA title defenses for big monthly house shows. Yoshimura, then, was his Gagne. Before Lou Thesz set foot in Japan, Rikidozan held a four-day training camp in Hakote. According to Yoshimura, Oki Shikina selected him to be Riki’s sparring partner because his body was the most similar to Thesz. Among other things, Riki tested a new counter to Thesz’s dreaded backdrop: a watered-down version of judo’s kawazugake throw [see demonstration] which readers will know better as the Russian leg sweep. Yoshimura was stunned when he watched Thesz practice with Harold Sakata a few days later and flattered by Oki’s comparison. JWA president Sadao Nagata (left) resigned in November 1957. The smash success of the Rikidozan-Thesz tour was not enough to cushion a blow that almost killed the JWA that November. After a four-year business partnership with Riki, Sadao Nagata took the advice of JWA advisor Yoshihiro Hagiwara and resigned from his positions as president of the JWA’s Kogyo (the promotion itself) and chairman of its shareholders’ association.4 Top promoters such as Hirotaka Hayashi, Hiroki Imazato, and Kunizo Matsuo also stepped down from the board of directors. Without these showbiz bigwigs, and without the backing of the man who had brought the yakuza into the entertainment industry thirty years earlier,5 Rikidozan was not prepared to run house shows as he had and was certainly not equipped to conduct business with local crime bosses, who would sabotage shows that were not held with their cooperation. After Nagata’s resignation, the roster traveled to Taiwan. Yoshimura claims that it was for two weeks, but there is only record of a November 27 show in Taipei, wherein Yoshimura beat Nagasawa. As the year ended, the JWA began taping a second weekly program, Pro Wrestling Hour, live on Friday evenings in Osaka. Yes, the two shows were held on back-to-back days, and yes, they had to fly from Osaka to Tokyo, because it was cheaper to do that than to broadcast from Tokyo in Osaka. This was not enough to make up for the losses in revenue. According to Koizumi, Rikidozan ordered Yoshimura to shoot on Surugaumi’s bad knee during an Osaka match on January 10. Yoshimura did as he was told, and essentially ended the JWA original’s career. On the February 7, 1958 edition of Pro Wrestling Hour, Yoshimura took part in puroresu’s first eight-man tag, which Riki refereed. Both it and Puroresu Fighting Man Hour were canceled in March 1958, as Rikidozan left the country for several months. As disclosed in a 1988 book by former secretary Yoshio Yoshimura, he was evading an investigation for a violation of the Foreign Exchange Act after having exchanged yen for American cash on the black market. Riki was certainly also eager to avoid confrontations over pay. When word got out that back payments had been delayed due to Riki’s own investments into his apartment rental business, over a dozen wrestlers stated their intent to go on strike if they were not paid before the next tour. Yusuf Turk even threatened to reveal Rikidozan’s Korean heritage. I do not know whether Yoshimura was among this contingent, but I am guessing that he wasn’t. He claimed in Konjo that he kept cool during this period, as the hard times in Osaka were still fresh in his memory, but some of those who had been JWA originals “and had not known hardship” did panic. Yoshimura wrestled on two shows while his boss was away. On May 31 and June 1, Toshio Yamaguchi held a pair of retirement shows at the Ogimachi Pool, and booked JWA talent with Riki’s approval. Yoshimura and Nagasawa teamed up with Yamaguchi in his final match, a six-man tag against Masahiko Kimura, Yoshinosato, and P.Y. Chang. Rikidozan returned to Japan in late August, and new program Mitsubishi Diamond Hour premiered on September 5. Just one week before the premiere, Nippon Television affiliate Yomiuri Television had started broadcasts in the Kansai market; now, both Osaka and Tokyo saw Rikidozan every other Friday evening (he had to alternate with Walt Disney’s Disneyland). Riki never truly mended his relationship with Sadao Nagata, but he had gained his protege, Akira Kato, as an employee.6 With his help, the JWA began to run house shows again. But if Koizumi’s theory is correct, and Rikidozan had been trying to emulate Fred Kohler with Yoshimura’s early push, then the “Chicago model” had failed. Mitsubishi Diamond Hour was built on Riki’s back, and Yoshimura was pushed to the sideline. In late 1958, as Rikidozan and Yoshinosato worked a month-long tour in Brazil, Yoshimura was part of a tour which began with perhaps the JWA’s worst attendances to date. In April 1959, Yoshimura married a woman named Sachiko, to whom he had been introduced by the director of Kinki’s sumo club. That same month, the JWA began to turn things around. Kato had proposed a wrestling version of the Nankyoku tournament, which was an annual all-star tour of traditional ballad singers.7 The result was the first World Big League, and it was a smash hit. The tour was buoyed by sales manager Hiroshi Iwata’s decision, inspired by tokusatsu hero Moonlight Mask, to turn the bland heel Clyde Steeves into the masked Mr. Atomic. For all its successes, this first iteration only had three Japanese entrants to the seven foreign combatants: Rikidozan, Kokichi Endo, and Toyonobori. The best that Yoshimura got were non-tournament matches against two of the more technical gaikokujin, Enrique Torres and Lord James Blears. In the autumn, Yoshimura was sent to Hawaii alongside Toyonobori, and as Koizumi has suggested, Blears may have requested to work with him. FOOTNOTES

-