-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

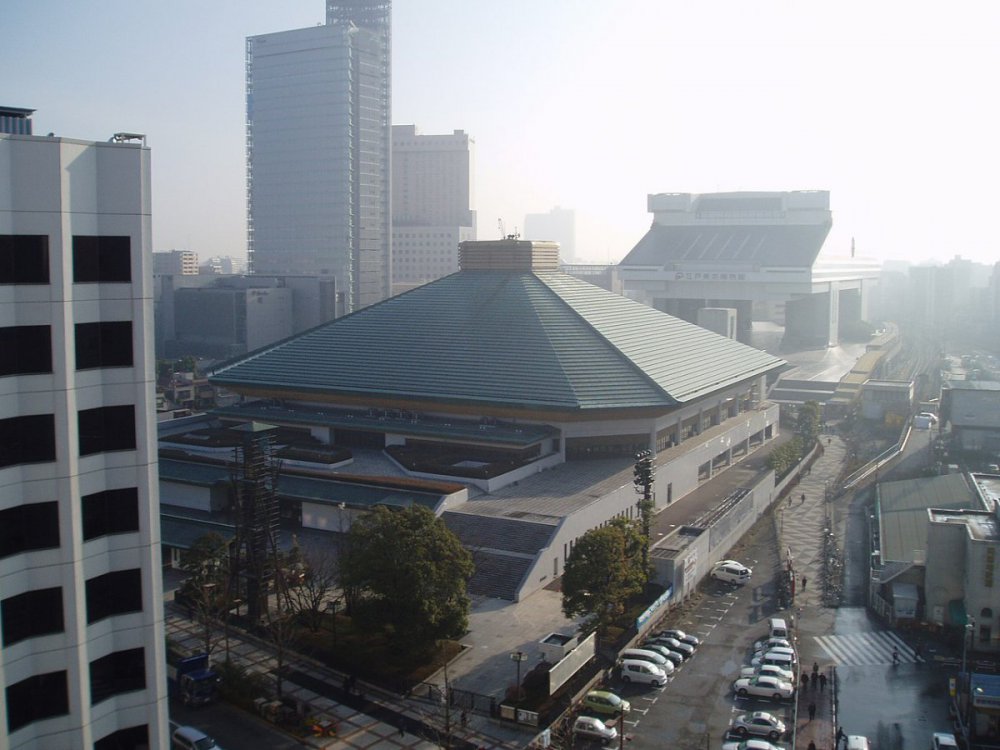

Ryogoku Kokugikan [II] Capacity: 11,098 Background When Tochinishiki Kiyotaka became president of the Japan Sumo Association in 1974, he confided in the board of directors about his intentions to replace the Kuramae Kokugikan. The venue had reappropriated the steel frame of a naval warehouse in its construction, and as a result it was in rough shape as early as the 50s. While he originally considered buying back the Nippon University Auditorium - that is, the original Ryogoku Kokugikan - Kiyotaka ultimately dropped the idea of reverting to a smaller venue, and set his sights on building a new venue on the north side of Ryogoku Station. The Sumo Association bought the property from Japan Railways, who had used it as the office of their bus company, and began construction in 1983. The ¥15,000,000,000 project was wholly self-financed. The building was completed in November 1984 and opened the following January. Wrestling From Inoki/Brody I to Genichiro Tenryu’s retirement and beyond, the second Ryogoku Kogukikan has amassed a considerable legacy in puroresu. In what would quickly become ironic in hindsight, AJPW were the first to bring puroresu to Ryogoku II, as Jumbo Tsuruta and Genichiro Tenryu defended their tag titles against the Road Warriors. They would run the building four more times in the next two years, before the Wajima ban made the venue NJPW-exclusive. (Mutoh-era AJPW would come to the venue for a 2004 PPV event.) Alas, they too would run afoul of the Sumo Association, with the debacle that was their December 27, 1987 show earning them a one-year ban. After that snafu, NJPW would stay in the venue’s good graces, although Masahiro Chono’s G1 Climax win would see him showered with seat cushions, a frowned-upon sumo fan tradition. (The “zabuton dance” would be banned in puroresu, and eventually became more strictly regulated in sumo.) Due to an elevator system allowing the dohyō to be retracted from the venue, joshi performances would not run afoul of sumo tradition in the new Kokugikan. As a result, AJW booked the venue in April 1986. It has never become a common joshi venue, but Ryogoku II continues to be open to such promotions to this day. In the 2010s, promotions such as DDT and even Big Japan Pro Wrestling booked the venue.

-

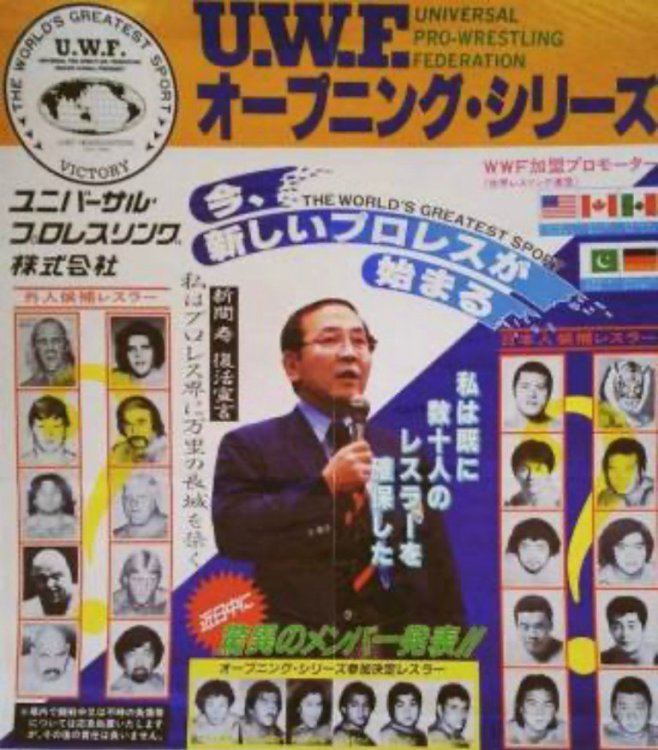

Nippon Budokan Capacity: 14,471* Background Originally built for the judo competition in the 1964 Summer Olympics, the Nippon Budokan was intended as a venue for martial arts competition. It was one of the final buildings designed by modernist architect Mamoru Yamada, with an octagonal roof inspired by the Yumedono Hall of Hōryū-ji temple. It expanded into professional sports in 1965 when it held Fighting Harada’s bantamweight title defense against Alan Rudkin, and its first musical performance had seen Leopold Stokowski conduct the Japan Philharmonic that same year. The Beatles’ Budokan concert the following year was hotly controversial among nationalists (including venue director and media mogul Matsutarō Shōriki). Over the years though, it’s become a moot point, as a series of live albums recorded by Western pop artists in the late 1970s made the Budokan Japan’s most famous concert venue. Wrestling In response to Toyonobori’s Tokyo Pro Wrestling, which was so bold as to hold its first show at Kuramae, the JWA brought puroresu to the Budokan in December 1966, with a Giant Baba title defense against Fritz von Erich. There was initial unease, as Fritz was not established in Japan, but the show would sell out as they built a program. Despite this success, the Budokan did not see puroresu return until the AJPW/IWE Rikidozan tribute show of 1975. After holding Antonio Inoki’s first different styles fight against Willem Ruska, and then his bout against Muhammad Ali, the Budokan saw relatively frequent usage for a few years. It was mainly booked by NJPW, although it would also hold the AJPW’s 1977 Champion Carnival final, a pair of late-70s AJW shows, and the Tokyo Sports show of August 1979. The final Budokan show of this period was in September 1980, and had been intended to feature Inoki's rematch against Willie Williams. When negotiations fell through, New Japan did not want to cancel the show, which would have come with a fee. So a show headlined with Inoki versus Ken Patera was retooled as a fan appreciation event, where kids got in free to plump up the numbers. After a second dark age from 1981 through 1984, AJPW and satellite organization Japan Pro Wrestling returned in June 1985, thanks to JPW president and former NJPW sales manager Naoki Otsuka. AJW followed suit that August. When All Japan was banned from the Ryogoku Kokugikan for their hire of retired yokozuna Hiroshi Wajima, they were forced to make the Budokan a more frequent destination. While NJPW, the Newborn UWF, and more would come to the venue in the ensuing years, All Japan would become its puroresu kings, eventually building to seven Budokan dates a year. In the 21st century, post-exodus AJPW continued to make it a frequent destination until February 2004, after which NOAH carried the torch as long as they could. After the All Together joint show in 2011, the DDT Peter Pan show in 2012, and NOAH’s Final Burning in 2013, the Budokan entered a third puroresu dark age until the 2018 G1 Climax, which booked three straight dates for its last shows. They repeated this the following year, but the COVID-19 pandemic would lead them to instead book Budokan for its final show of 2020. As NOAH was acquired by CyberAgent, though, the promotion returned to the Budokan in 2021, and has held three shows since. AJPW booked the venue for its 50th anniversary show in September 2022. Even joshi made its first showing since the twilight days of AJW, with the Bushiroad-backed Stardom holding its tenth anniversary event. The future isn’t looking too bad for puroresu at the Budokan. *The venue can stretch itself as far as 16,300, as it did at the peak of AJPW’s shows.

-

This post cannot be displayed because it is in a password protected forum. Enter Password

-

I have no first-hand memories of Hall as a performer, but I just want to say one thing. When I was somewhere between 10 and 12, my cousin showed me that Monday Night War doc from 2004, and I thought he was the coolest guy I'd ever seen. My only internet access at that time was my grandfather's computer, which he would let me borrow when I visited him every week. I remember printing out Scott's Wikipedia page to read when I got home, because my grandpa wouldn't let me on YouTube to actually watch clips of him. RIP (I did the same with X-Pac. I was a kid, okay?)

-

This interview is from the now inactive official Japanese site for the film Rikidōzan, a 2004 Korean-Japanese co-production. I am guessing that it was conducted in early 2006. Ever since completing my Broken Crown series in December, I had been preparing a longform article about Takeuchi and the history and impact of Gong magazine. I have decided to shelve that piece, which I had planned to publish on the tenth anniversary of Takeuchi's death in May, because I am not confident that I could do the subject justice without direct interviews with ex-Gong journalists. I simply do not have the clout, the money, or the fluency to make that happen. I may cannibalize what I had written for content here, as I want my work in this forum to encompass puro journalism history. This interview was among the resources I had used. Kosuke Takeuchi was the founder of Monthly Gong, the predecessor to Weekly Gong, and a well-known commentator for All Japan Pro Wrestling Live. He is also one of the most knowledgeable people in Japan about Rikidōzan. His encounter with Rikidōzan eventually led him to build a career as a professional wrestling reporter which has spanned more than 40 years. We asked Mr. Takeuchi to talk about his memories of Rikidōzan, his own relationship with professional wrestling, and the appeal of the movie "Rikidōzan" as seen through the eyes of a professional wrestler. --First of all, please tell us about your first encounter with Rikidōzan. The first time I saw Rikidōzan was on a street TV broadcast, and it was the first match when Ortega came to Japan in 1955. It was the debut match of the yokozuna Azumafuji, who had switched from sumo to pro wrestling. However, the yokozuna could not compete at all, and his performance was poor. Then Rikidōzan came out and challenged the huge Ortega with a karate chop, which had a tremendous impact. I thought, "Wow, Rikidōzan is strong!” After that, I didn't care about Azumafuji anymore; it was just the image of Rikidōzan that had been burned into my mind. The first time I actually saw a match was in 1959. It was a match between Rikidōzan and a masked wrestler named Mr. Atomic. I had happened to see a flyer that said elementary and junior high school students could see the match for 50 yen, so I looked up a map and went to the Denen Coliseum.1 --Was he very popular among elementary and junior high school students in those days? In our days, sumo wrestlers Tochinishiki and Wakanohana were in their prime, and they were popular at school. But the moment pro wrestling came in, the children's tastes changed. They used to wrestle in a circle in the schoolyard, but now they are all playing wrestling. So, every Friday, we would go to the street TV to watch the matches. To tell you the truth, though, the screen was too small to see! So I would go to a nearby yakisoba shop that had a TV set, buy a ticket for noodles in the evening, and go watch the match when it started at 8pm. Eventually, though, I was the only one eating and watching the TV at the restaurant. When it was a big tournament, everyone was interested, but when it became a regular TV program, the venue was small, no big players came, and it was not popular.2 I felt that I was a little behind the times, but I still went to see the matches. --What kind of impression did you have of Rikidōzan? He did wrestling that was easy to understand, even for children. There was a foreign wrestler who was just bad, and at first he was beaten thoroughly. Then, at the last moment, he would explode with anger and defeat them with a karate chop. It's just like Gekko Kamen and other heroes. The way the monsters (laughs) come one after another is just like Rikidōzan’s monster slaying. That's why it's no wonder it's so popular with children. However, now that I think about it more calmly, I realize that Rikidōzan was very good at some things. At some point, the TV broadcast started to end when he was in a pinch. The match would not end completely. This caused me a lot of frustration, and even as a child, I felt the need to buy a newspaper to find out the results. It was right around the time when evening sports papers came out, and the front and third pages always had articles about wrestling. At that time, the regular morning sports paper cost 10 yen, but the evening sports paper cost 5 yen, so you could read a lot of articles on wrestling for half the price. Still, for a child, even 5 yen was a waste. That's why I sometimes picked up the evening paper the next morning. --What is Rikidōzan’s most famous fight for you? In my memory, the only one I can remember seeing is the match with Destroyer. It was 1963, the year of Rikidōzan’s death. By that time, I had become more discerning about wrestling, but even so, Destroyer was nothing short of amazing. The match he had with Destroyer in May of that year was the best! I don't think there is a better match than that. At that time, all masked wrestlers had black masks, but Destroyer was the only one with a white mask. This made him look very creepy. Also, the Destroyer had taken the belt from Fred Blassie in the U.S. the year before, so I thought he was stronger than Blassie. He was stronger than Blassie, and he used a technique I've never seen before, called the figure four hold. There were so many mysterious elements that I was excited even before I arrived. On the day of the match, we were seated in the middle of the first floor. This was the first time we saw the "figure four" technique in action. It's not a rare technique now, but at that time, both [the Destroyer and Rikidōzan’s] legs went numb when he applied the technique, and the referee made them take off their ring shoes because we couldn't break free on our own. When you think about it, though, there was no need for that! It's not like taking off the ring shoes was going to solve the problem. But at the time, I thought that was a great idea (laughs). --I wouldn't have thought of it now (laughs). I'd like to ask you a little bit about yourself, Mr. Takeuchi. After working as the editor-in-chief of Pro Wrestling & Boxing, you were involved in the launch of Monthly Gong. There was a facility called the Riki Sports Palace that Rikidōzan had built in Shibuya, and every Friday they would hold a TV match there. It was rather inexpensive - I think it was 300 yen at the time - so I went there as long as I could afford it. One day, I happened to buy a copy of Pro Wrestling & Boxing at a store and was reading it on a bench when someone asked me if the magazine was interesting. I said something about it being interesting or boring, and [Yukio Koyonagi] pulled out his business card and said, "Actually, I'm the editor-in-chief." (laughs). We parted ways at that time, but a few months later, he contacted me and said, "We have a vacancy, are you interested in coming?" (laughs) People around me said, "You don't have any experience, so all you can do is fetch tea," but I decided to go because I liked the job. That was my start. I started working in the middle of high school, so I was 18 years old. After working there for about a year, I decided I wanted to make my own magazine (laughs). I know it sounds cheeky, but I was getting frustrated with the way things were going. Just around that time, Tokyo Pro Wrestling had launched, so I decided to quit making magazines and apply for a job there, as they said they were hiring because they didn't have anyone yet (laughs). So I thought I had made my decision and turned in my resignation to the company, but then [Koyonagi] asked me what I was unhappy about. I told him, "The way the magazine is made now is not very interesting." He asked me if I could make it better, to which I replied, "I'd like to make it better.” He answered, "Then I'll make you editor-in-chief." Oh, that's a different story then (laughs), so I was made editor-in-chief at the tender age of 19. --That's an amazing story (laughs). (laughs) But I was still young and inexperienced in many ways. Then, when I was thinking about what to do next, Baseball Magazine, the company that published Pro Wrestling & Boxing, filed for bankruptcy. And the top people at the time [including Koyonagi] went independent and started Nihon Sports Publishing Co. When they decided to create a new magazine, they decided that wrestling was the one magazine that had no competition, so they asked me to join them again. That's how I ended up working on the first issue of Monthly Gong. --What did you find unsatisfactory about the way the magazine was produced? I was not able to cover the topic of Rikidōzan. Rikidōzan was the reason why I fell in love with professional wrestling. That's why I wanted to write about Rikidōzan, but he was already dead and there was nothing new to talk about, so they wouldn't cover him, and I was really frustrated. So as soon as I started Gong, I started doing a lot of special features on Rikidōzan (laughs). At that time, it had been about four or five years since Rikidōzan’s death, and the response was still good. There was a demand for it. At that time, I decided to collect all kinds of Rikidōzan photos and materials, and this is what I did most enthusiastically. Because Gong was first published in 1968, there was no material on Rikidōzan. In the end, I had to gather materials from existing newspapers and magazines, but I wanted to have a complete history of Rikidōzan, so I collected everything I could. Whenever I met someone related to Rikidōzan, if I found a good photo, I would ask them to give me one. Thanks to this, I think I accomplished my goal fairly well. I'm proud to say that I have the most photos in Japan. --In fact, now that you have come into contact with Rikidōzan through your work, you have come to understand a side of him that you did not know when you were a child. In the end, it's not so much about Rikidōzan, but about Mitsuhiro Momota, isn't it? He was not the hero we knew. He was a human being, with a very strong ego. But even after knowing that, I can forgive Rikidōzan. I feel that is more like him than the well-behaved Rikidōzan, and I was not disappointed. The greatness and charm of his fights far outweighs that. It is true that Giant Baba, Antonio Inoki, and others have all gone on to create their own eras, but it is impossible to surpass Rikidōzan. First of all, Rikidōzan’s background was too different from theirs, and I don't know how such an ideal wrestler could have existed in that era in terms of body shape and mood. I also have the impression that he suddenly disappeared from the scene as a superstar. And since he met such a tragic end, he's more of a legend than a superstar. --This is a little off the topic of Rikidōzan, but speaking of Gong, you covered Mil Mascaras quite a bit, didn't you? I heard that you yourself are quite a fan. Yes! (laughs). At that time, I wanted a hero for the magazine. For example, there was a movie magazine called Roadshow that sold like hotcakes after Burning Dragon became a hit, which featured Bruce Lee. Magazines were just starting to shift from black and white to color, and I was looking for a new hero to match this trend. It wasn't Giant Baba, Antonio Inoki, or even Rikidōzan anymore. It was then that I noticed that there was a guy in Los Angeles who changed his mask every game. Since there is usually only one type of mask, the fact that he changed his mask every match brought to mind the image of a seven-colored mask or a man with seven faces. Now I had to gather materials for Mascaras (laughs). There were almost no such materials in Japan, so I went around to all the news agencies, looked at all the negatives, and bought up all the pictures that had Mascaras in them. I also asked the local photographers to send me just the Mascaras photos for the time being. I felt like I had to go all the way (laughs). In the end, thanks to my three years of following Mascaras, when he first came to Japan, there was already a boom. --You also did commentary for All Japan Pro Wrestling and other matches, didn't you? That's because, when Mascaras came to Japan, the producer of the show asked me to be the commentator for Mascaras. There were already two professional commentators, so I was sent to Mascaras' match.3 In that sense, I can say that I've benefited from everything I've done up to that point (laughs). By the way, speaking of Mascaras, there was that theme song, "Sky High" by Jigsaw, wasn't there? The director [Susumu Umegaki] happened to select it as the background music for the trailer of the TV show: "Mascaras will be appearing next week." It certainly fit the image of the show, and the response was great, so they decided to play it at the venue when he came. This was a time when even the WWF (now WWE) did not have theme songs. So they played it once during Mascaras' entrance, and it exploded (laughs). That started the "Sky High" boom.4 --That's an anecdote that gives us a glimpse behind the scenes of history (laughs). Back to the topic at hand, what are your impressions of the movie Rikidōzan? Before seeing the movie, I didn't have high expectations, to tell you the truth. I thought it would be impossible for a Korean star to play Rikidōzan, and I didn't think the actors could play Rikidōzan. I also thought that it would be just a superhero story, or that it would end up being a pretty story. However, when I actually saw the movie, I felt that it was so different from what I had expected. I thought it was amazing that they were able to capture the essence of Rikidōzan so well. First of all, the actors are all wonderful. They were all in the right place at the right time. Especially Seol Gyeong-gu, who played Rikidōzan, I felt that he was the only one who could do it. He had to perform all the movements in the ring, and from our point of view, there was no unnaturalness in the matches. I can only say that it was amazing that they were able to clear this most difficult part. Also, there was no waste in the selection of episodes, and even though Rikidōzan was the subject of the film, the good times and good scenes were covered properly. The historical research was also very well done. It made me wonder what kind of knowledgeable person wrote the screenplay. It is true that there are some aspects of the story that people who like Rikidōzan may not accept, and I think there are pros and cons. But on the other hand, I want people to know that this was also Rikidōzan. I want people to see this film because it's a film for this day and age. I want people to feel the character of the hero Rikidōzan, or rather, his “hungry” spirit, which the people of today do not have. --Thank you very much. By the way, I heard that you are currently preparing a book about Rikidōzan. I'm working on a book about Rikidōzan and the alleged fight against Masahiko Kimura. The main title of the book will be "Which one was betrayed?” After all, the most scandalous and mysterious of all Rikidōzan’s matches is the Rikidōzan-Kimura match, which took place at the Kuramae Kokugikan on December 22, 1954. Rikidōzan won the match, but even now, 51 years later, there are still many things we don't know. It was a match that all the reporters and writers who had covered pro wrestling were interested in, but could not come to a conclusion about. That's why I really wanted to try my hand at it and come to my own conclusions about what this match was all about, what happened in the end, and who betrayed who. I started researching about three years ago, and I'm about halfway through writing it now. I have all the materials, so I'm taking my time and not rushing.5 --I am looking forward to its completion. Thank you very much for your time today. FOOTNOTES 1. Mr. Atomic was a gimmick created for Clyde Steeves by sales manager Hiroshi Iwata. The previous year, Gekko Kamen had started the tokusatsu television program, and Iwata wanted to create a villain who tapped into that niche. 2. Takeuchi is referring to Puroresu Fight Man Hour, the JWA’s first attempt at a weekly television program. This program was taped at the Japan Pro Wrestling Center/Rikidōzan Dojo, rarely featured foreign talent, and often saw Rikidōzan work as a commentator or referee instead of wrestle. It would be terminated in March 1958, as Rikidōzan fled the country to evade investigation into his use of black market money to hire American wrestlers. 3. Takeuchi was made a special commentator for Mascaras starting in 1978. 4. So intertwined was Mascaras with Takeuchi that “Sky High” would be played at his funeral. 5. Takeuchi would never finish the book. In the fall of 2006, he suffered a massive stroke during his morning commute which would leave him bedridden and unable to speak until his 2012 death. Toshinari Masuda would publish the 700-page bestseller Why Didn’t Masahiko Kimura Kill Rikidōzan? in 2011, but that book was a biography of Kimura.

-

Also thought I'd share a photo from the September 11 Pyeongtaek show (click for full size). Samson Kutsuwada worked this tour as "Tiger Mask", half a decade before NJPW made that tie-in a reality. According to an article on the Showa Puroresu fanzine's website, Kutsuwada had previously worked this gimmick in a June tour of Korea. By this time, the original Tiger Mask anime had been syndicated to the region, with great success.

-

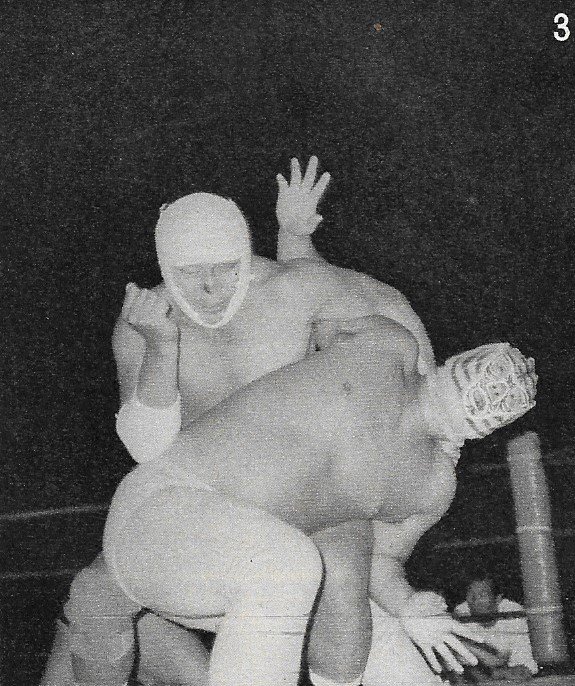

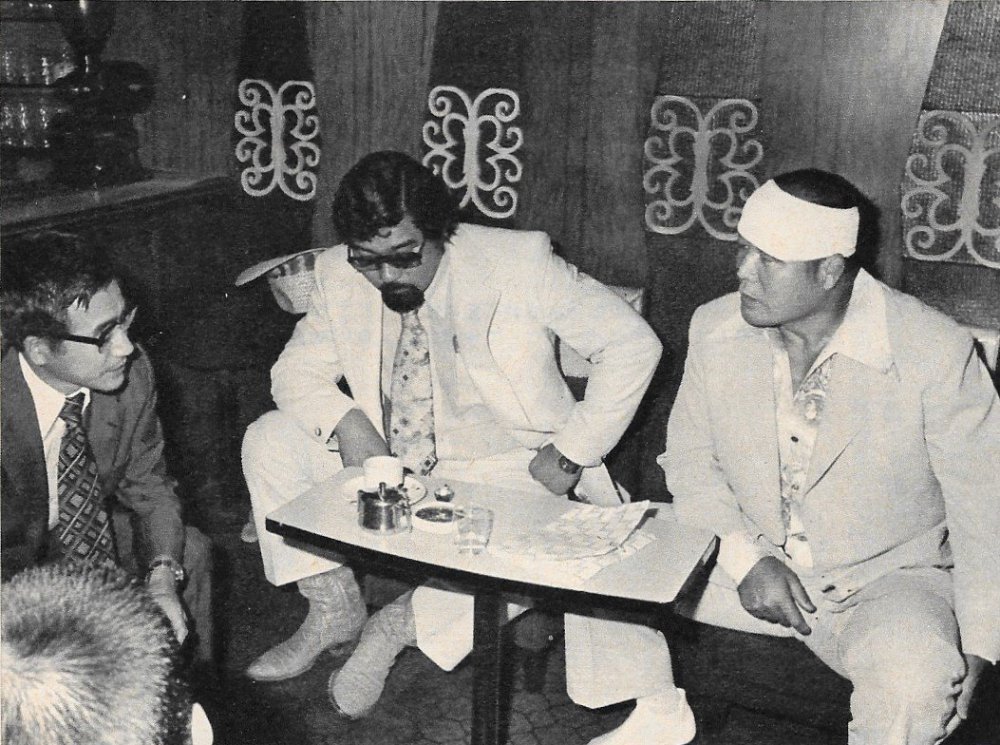

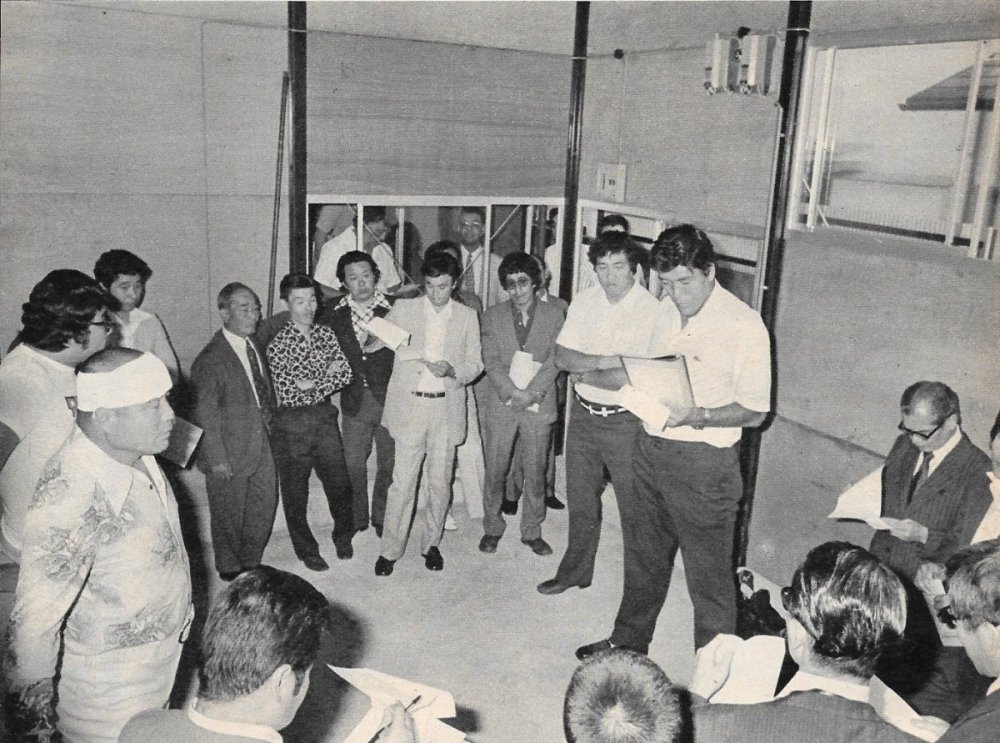

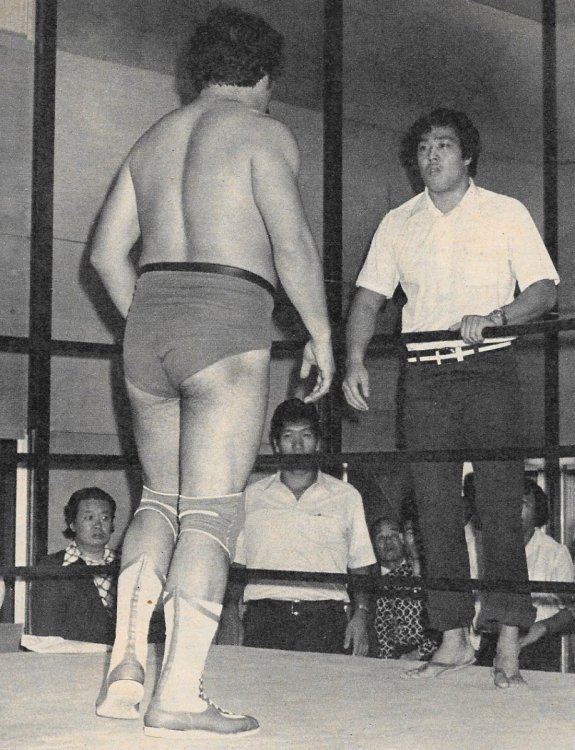

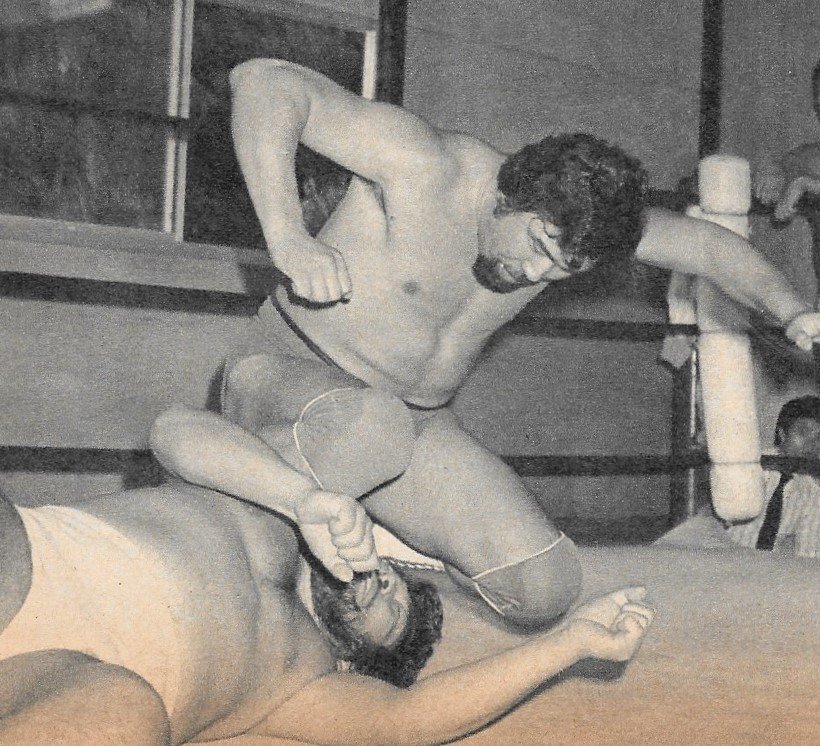

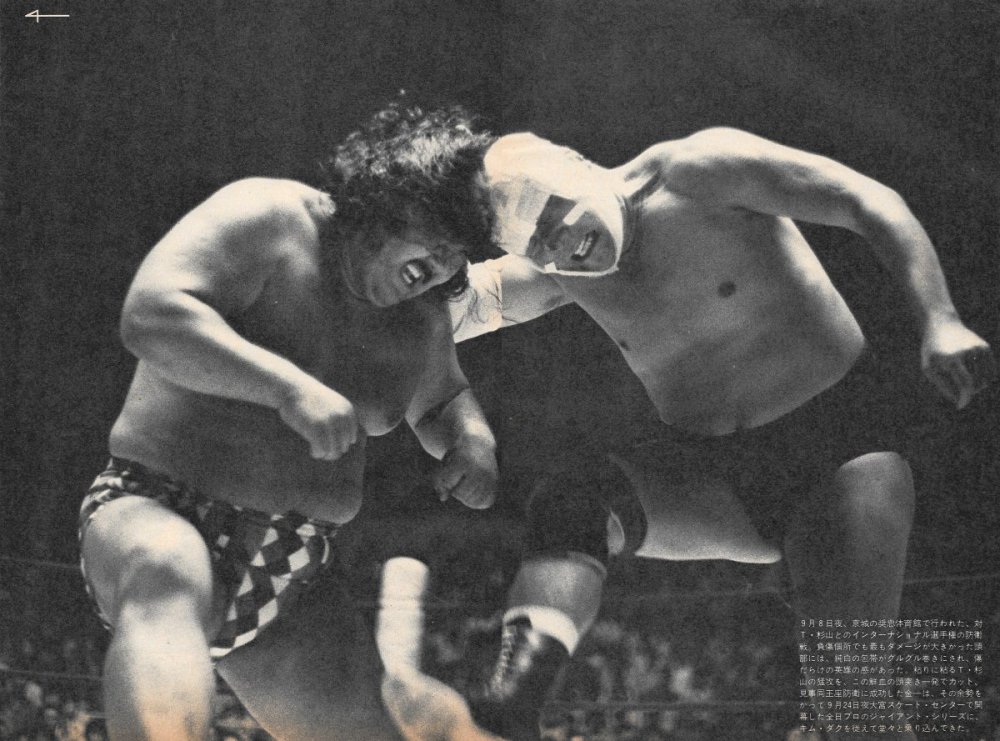

The following is sourced from "大木とキムの殴りこみで"プロレス日韓戦争"開始", an article written by Seibu Kikuya and published in the November 1976 issue of Monthly Pro Wrestling, pg. 78-81. It has been rewritten and rearranged for clarity and flow. OKI AND KIM'S ASSAULT STARTS "JAPANESE-KOREAN PRO WRESTLING WAR" Kim Il (Kintaro Oki) and Kim Duk (Masanori Toguchi), the Korean master-disciple duo, are set to face Giant Baba and Jumbo Tsuruta in the final match of the AJPW Giant Series at the Kuramae Kokugikan on October 28. The catalyst for this was a written challenge from Oki, sent from Korea, for the International Tag Team titles held by Baba and Tsuruta. In summary, the letter read: “On May 13, at the Kawasaki City Gymnasium, Oki and Nankaizan [Kang Sung-Yung] had the opportunity to face Baba and Tsuruta, albeit in a non-title match, but they were unsuccessful. Fortunately, Oki now has Kim Duk as his partner and will challenge Baba and Tsuruta again for the tag titles. Masanori Toguchi, aka Kim Duk, has grown into a young warrior after three years of training in the US, and has gained the ability and popularity to surpass Oki. We are confident that he will be able to show his Japanese fans how well he has matured, and that he will be able to capture the title. We hope that Baba and Tsuruta will graciously accept this challenge.” Baba was surprised. After hearing from Samson Kutsuwada and others that Oki was not in a condition to perform, Baba had decided to postpone the first show of the Giant Series at Omiya, where Oki was scheduled to wrestle. The reason was that Oki had been scheduled to defend his Asian Heavyweight title against Waldo von Erich. Baba said, "Anyway, I am worried about Mr. Oki's injury and his injury, and I don't have enough information about Toguchi.” He immediately inquired at the PWF headquarters about Toguchi's eligibility to challenge, but the reply was withheld, saying that a decision would be made after Mr. Oki's arrival in Japan. This seemed to have irritated Oki again. On September 20, Oki arrived in Japan with Toguchi. The flight from Seoul to Tokyo usually takes less than two hours, but this was quite unusual for him, as he usually arrived at the airport just before the opening of the show. Oki flies in with bandages, saying the challenge comes before the cure Baba was understandably concerned about Oki's injury. Oki had just been seriously injured in a car accident. It was after 11:00 p.m. on August 31 when Oki was involved in a traffic accident. Oki was on his way home from a dinner with friends outside of Seoul when he collided head-on with a cab as he was approaching Han River Road on Route 3. Oki, who was riding in the front passenger seat, was rushed to Soonchunhyang Hospital in Namsan, Seoul, after he crashed through the front windshield and became a bloody mess. He suffered lacerations on the forehead, face, right elbow, and right palm, as well as bruises all over his body. He was seriously injured, with a projected recovery time of one month. The most severe injury was the forehead laceration, for which a combined plastic and reconstructive surgery was performed by cutting and grafting about nine square centimeters [approx. 3.5”] of skin from the right thigh. If Oki hadn't had the world's hardest head, trained by head-butting, he might have been killed. On the night of his hospitalization, Oki had a high fever of 39 degrees Celsius and could not sleep at all. However, on September 5, the sixth day of his hospitalization, Oki ignored the doctor's protests and forcibly discharged himself from the hospital, before his stitches had been removed. This was because a four-show domestic tour was set to begin on September 8. The tour featured freelance wrestler Thunder Sugiyama and All Japan wrestlers Samson Kutsuwada, Kazuo Sakurada, Mitsuo Momota, and Atsushi Onita. On September 8, they had scheduled an afternoon show in Incheon and an evening show in Seoul. Shows in Daegu and Pyeongtaek would follow on the 9th and 11th. Oki participated on all shows with his head heavily bandaged, as if he were wearing a white mask. On September 8, Oki returned to the ring to wrestle Thunder Sugiyama. “Not only could I not use my head butt, but my right hand and right leg didn’t work as well as they should. However, I was prepared to die in the ring," said Oki. In Korea, a wrestling show without the "hero" Kim Il would not be possible. Fans come to the event to see Oki. For his fans, Oki risked death in the ring. But this was not a good thing for his wounds. He had broken all the doctor's injunctions, “not to move and not to sweat”. It is only natural that Baba, who heard the report of Kutsuwada and others after their return to Japan, was concerned about the extent to which Oki had recovered. Oki countered. "I challenged because I was confident that I could win. I did not issue the challenge before I was injured. I don't need Baba's concern about my injury." He was so irritated by the lack of response that he stormed into Japan four days before the tour was set to begin. Oki and Toguchi held a press conference at the Rio coffee shop in Shibuya on the 20th, at 6 p.m. His head was still bandaged and the lacerations on his nose and the corners of his eyes had not fully healed, but he spoke in a passionate tone. Oki expressed regret for the worry he had caused to his Japanese fans in the car accident, and after explaining why he had challenged Toguchi to be his partner in the inter-tug, he vented his anger: “It's been more than a week and I still haven't received a reply. I have also written to PWF President Lord [James] Blears, but he has not responded either. I've been trying to negotiate with these slow-moving men by letter and phone from Seoul, but I just can't seem to get anywhere, so here I am. As the last Inter Tag Team Champion when I was with Japan Pro Wrestling [alongside Umanosuke Ueda], of course I have the right to challenge for the title, and I can't adjust Kim Duk's schedule if I don't hear back from him soon. If I don't get a decision by the end of the day, I will not participate in the Giant Series. I'll send Toguchi back to the U.S. tomorrow, and I'll go back to Seoul.” All Japan external relations head [Ryozo] Yonezawa, who was attending the press conference at Oki's request, panicked. "We have been in touch with Blears again and again," Yonezawa said. "Blears said that he had no problem with Mr. Oki's qualifications for the challenge. However, we are still gathering information on Mr. Oki's nominee, Kim Duk, who is a part-timer. I think we should have reached a conclusion by now, but the truth is that we are aware of Masanori Toguchi of Nippon Pro-Wrestling, but we do not have enough information on Kim Duk.” When Yonezawa explained the reason for the delay, Toguchi snapped at Yonezawa: "That's ridiculous. I have experience in the United States. If you call the American promoter, you can find out right away." The bearded Toguchi, who had grown two sizes since before he came to the U.S., had an impressive body and face. After a heated exchange of opinions, Oki escalated the conditions to "either Tokyo, Osaka, or Nagoya," and the day ended with a promise from All Japan to give a definite answer by 3:00 p.m. tomorrow, the 21st. Kim Duk, who grew up in Tokyo and devoted himself to Oki Some of you may be wondering why Oki's letter of challenge refers to Toguchi as "[his] successor," so I will explain the relationship between Oki and Toguchi. Born in Kanamachi, Katsushika-ku, Tokyo in 1948, Toguchi was a promising young judoka when he was a student at Shutoku High School. However, Toguchi had been fascinated with Oki, a "hero" born in his parent’s homeland of Korea, since his boyhood. He tried to drop out of high school and enter professional wrestling, but Oki gave him counsel, and since then he had come to look up to Oki as an older brother and a mentor, consulting him on everything. When Toguchi was scouted by Masahiko Kimura, the director of the Takudo University judo club, Toguchi visited Oki at the Taito Gymnasium with Mr. Kimura, asking to see Oki. At that time, Oki asked Kimura, "Please help Toguchi to become a judo champion in Japan," and recommended that Toguchi also be under Kimura's care. However, upon his graduation in March 1967, Toguchi "made up his mind" to join Japan Pro Wrestling. He flew to Korea to become a trainee at the Kim Il Dojo, which at the time was located in a secret garden in Seoul. After six months of training under Oki, Toguchi made his debut as a young Japanese wrestler in August 1968. Toguchi therefore said, "At Japan Pro, Mr. Oki and I would have been considered senior and junior, but I consider Mr. Oki my mentor. I would do anything for my respected teacher.” Toguchi's expression is not an exaggeration. In October of last year, Toguchi appeared in Korea for a week. When he received a call from Oki asking him to participate in a mock teardown of the newly built Bunka Gymnasium and Kim Il Dojo in Seoul, he left Minneapolis for Japan to take a flight to Seoul, not even stopping long enough to visit his parents. Toguchi had arrived in the U.S. in December 1972, near the end of the Japan Pro era. At that time, the promotion could not afford to send out young talented wrestlers for hakutsuke, so Toguchi's trip to the U.S. was entirely due to Oki's consideration. Toguchi received a red gown with gold tiger embroidery that Oki had worn, and he went to the States by himself. He says that he had a hard time without food and drink in America. However, Toguchi rose quickly last year after he entered the AWA and was recognized by its king, Verne Gagne. He had been scheduled to challenge for the AWA World Championship for the first time in November, having beaten the best of the best. Kim Duk's schedule was tight as he had become so popular. However, when Toguchi received a call from Oki, he said, "It's thanks to Oki-san that I became a star in America. For Oki-san's sake, I am willing to give up my chance to challenge the AWA title." He forcefully canceled his AWA dates schedule, the most important period for a wrestler before his first challenge, and flew to Korea. Toguchi's trip to Japan this time was also "for the sake of the general”. Toguchi, who had played an active role in the Korean series from September 8 in helping a seriously injured Oki, was scheduled to fly to the North Carolina territory instead of stopping in Japan. However, Toguchi was worried about Oki's condition in the Giant Series even though he was still recovering from a serious injury. When he was told of Oki's regret over his defeat by Baba and Tsuruta in May in a team with Nankaizan, Toguchi decided to go with him, and cancelled his bookings. Oki and Kim crash the opening ceremony of All Japan's new dojo. A fight that was sold, and a showdown in Kuramae. September 21, when the master-disciple duo of Oki and Toguchi were forced to make a definite decision, was also the opening day of All Japan’s newly built training camp and dojo in Setagaya, Tokyo. It was just after 3:00 p.m. The priest officiated the dojo opening without incident, but just as the attendees were relaxing, Oki and Toguchi arrived. For a moment, there was an atmosphere of ill will. Oki's face stiffened up as he read the schedule of the Giant Series Championships handed to him by Yonezawa. Oki pressed Baba. “Abdullah [the] Butcher and Waldo von Erich’s challenge is already on the schedule," he said. “What will happen if the foreign team wins, if we are going to challenge the winners of the Neyagawa title match on October 24? You've got to beat us first!” Baba responded. “Are you challenging for the titles, or are you challenging us? We can't change our previous agreement with the Butcher's group.” Oki decided. "Okay! There’s no point in challenging the foreigners. Even if you lose, I'll still challenge you. Nagoya or Tokyo!” Oki's challenge continued. The Nagoya show on the 22nd, held at the Aichi Prefectural Gymnasium, had already booked its main event: the sixth in Jumbo Tsuruta’s ten-match Trial Series, against the Butcher. Meanwhile, the October 28th show at Tokyo’s Kuramae Kokugikan had scheduled a PWF Heavyweight championship match between Baba and Butcher. After consulting with NTV officials, Baba had agreed to face Butcher at the Kuramae Kokugikan, as if he had been sold a fight. Oki's face lit up, and he turned his focus toward Tsuruta, who had been following Baba closely. Pointing at Toguchi, he said “Can't you even greet your senpai?” Toguchi was more than four years Tsuruta's senior. Tsuruta, however, who had been watching Oki's fighting and snapping at his mentor, glared silently at Oki and Toguchi. Meanwhile, Toguchi was dressed in trunks. “Show him how strong you are.” At the sound of Oki’s voice, Toguchi stepped into the ring, from which the altar had just been cleared. “Ito, let him have it!” Baba shouted angrily, but [Masao] Ito was no match for Kim Duk. Atsushi Onita followed him, and was also lightly beaten. Kim then performed a blockbuster drop [translator's note: Japanese term for fallaway slam], shoulderbuster, dropkick, human windmill [re:butterfly suplex], and various other moves. Tsuruta was so shocked that he ran to the ring in his shirt. The Great Kojika, Kazuo Sakurada, and others rushed to restrain him. As Oki reminded Kim that today was the dojo’s opening, he stopped, and the situation deescalated. Tsuruta and Kim grab each other at the doorway to start the series of fights. The confrontation at the dojo opening was only a minor one, but the "fight" between the Japanese and Korean master-disciple duo got into full swing in the opening show of the tour. It was September 24, in Omiya. Oki had been challenged by Erich for his Asian Heavyweight title in the main event, but he was not yet in full fighting condition. With the Butcher’s intrusion, the match was declared null and void. Kim, trying to protect Oki, got into a showy brawl with the Butcher, but when Baba entered the ring to stop it, Kim said, “Why are you coming in here?” A furious Baba was responded in kind. “Because you’re all sloppy,” he said. “If you’re going to be such a lousy face, then leave!” This time, Oki got angry. “What? If that’s so, then I’ll settle things with you right now.” He challenged Baba, but Japan Pro’s representative, [former JWA president Junzo] Yoshinosato, intervened, and the matter was settled. However, this was not the end of the story. Kim, who was on his way back to the special waiting room after helping Oki, bumped into Tsuruta in the hallway. Eye to eye, they grabbed each other at the same time. It was a loud exchange of karate and punches. All the young men came to the scene and finally separated the two fighters, but this was the decisive moment between Tsuruta and Kim. The next day, the Japanese and Korean master-disciple duos fought each other at every turn. They were always separate in the waiting room and in their behavior, and whenever they looked at each other, they were fighting each other. The cool-headed Baba always kept his composure, but the bloodthirsty Oki, and the young Toguchi and Tsuruta kept their heads in the sand. The young players had no time to relax, lest Tsuruta and Toguchi get together. If they met, they would run amok. With the Butcher and The Destroyer joining the fray, the Giant Series, filled with a deadly atmosphere, is running toward the final show, which will be an explosive battleground. Tsuruta meets Kim Duk, his first 'native' rival.

-

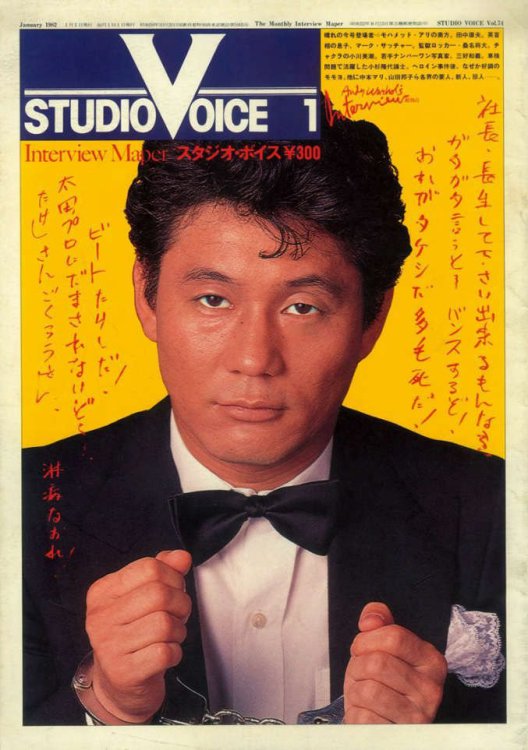

[Credit to this Igapro article for most of this information.] Flagship NJPW program World Pro Wrestling entered a turbulent period in 1983. As Tiger Mask departed and unmasked in August, after he and manager Shunji Koncha had disagreed with the plans for a coup, the ratings began to fall under 20%. The UWF and Japan Pro Wrestling departures followed in 1984; the latter chunk was so devastating that TV Asahi had to hold a press conference to make it clear that World Pro Wrestling would continue. The popularity of the Machine Army and the acquisitions of Bruiser Brody, Shiro Koshinaka, and Kevin & Kerry von Erich had brought some hope, but AJPW’s return to prime time and the end of New Japan’s WWF partnership were a devastating pair of blows. While the NJPW/UWF feud is now regarded by puroresu fans as a creative high point of Showa period New Japan, and partnerships with Calgary booker Tetsunosuke Daigo and Bill Watts’ Mid-South brought new foreign blood into the company, by the autumn of 1986 there had been talk of dropping the program outright. This was tempered by NJPW chairman Hiroshi Tsujii and managing director Takahira Nagasato. Both men were TV Asahi executives who had received those seats in the network takeover of 1983, and both mens’ careers were deeply linked to World Pro Wrestling in particular. In 1969, when the JWA sought a second network deal to sabotage the chances of the Great Togo’s tentatively named National Wrestling Enterprise, Tsujii was the executive they approached. Nagasato, meanwhile, had overseen the program as the head of the network’s sports department. It was agreed, though, that change was necessary. World Pro Wrestling was shifted to the same time on Mondays, a timeslot it had previously held for much of its original run as a Japan Pro Wrestling/JWA program. The change began on October 13, 1986, but would only last six months. The program was preempted by other programming on several occasions, which had not been an issue on the Friday timeslot. Masa Saito’s first match in NJPW since 1984, a singles bout against Inoki, was thrown out due to the interference of a hockey-masked pirate. This angle had been set up when Keiji Mutoh was attacked by a man in this costume in Tampa, but according to the kayfabe-breaking book by referee Mr. Takahashi, Victor Manuel had misunderstood his assignment and handcuffed the wrong man to the rope. It was a disaster. By this point, the network agreed that “major surgery” was necessary to save the program. World Pro Wrestling received a grand, 90-minute sendoff on April 6 before the new era began, as the rebranded and retooled I Can’t Wait Until The Give Up!! World Pro Wrestling began airing at 8pm the following night. This had previously been the timeslot of the popular variety show Beat Takeshi’s Sports Taisho, and this matter warrants a digression. An infamous incident involving top TV Asahi entertainer "Beat" Takeshi Kitano (pictured here in 1982) would lead NJPW to a brief, disastrous television experiment. Beat Takeshi’s Sports Taisho saw the titular entertainer and his two groups of tarento apprentices, the Takeshi Corps and Takeshi Corps Sepia, compete in sports against teams that would consist of audience members, fellow entertainers, or professional athletes. The program had suffered a mortal wound after a December 1986 incident. When a reporter for weekly tabloid FRIDAY approached Takeshi and a much younger vocational student that he was suspected to be dating on the streets of Shinjuku, he sprained her neck and back as he shoved his tape recorder in her face and yanked her by the hand. Around 3am that night, Takeshi and various Corps/Corp Sepia members stormed FRIDAY’s headquarters, brandishing umbrellas and a fire extinguisher and assaulting five employees. As Takeshi awaited his trial, he and his accomplices withdrew from their entertainment activities, and the renamed Sports Taisho was left to make do with the few Takeshi Corps members who hadn’t been involved. With both World Pro Wrestling and Sports Taisho in decline, TV Asahi decided to retool the former into a wrestling-variety hybrid program in the timeslot of the latter, hoping they could broaden NJPW’s appeal. This new program would be produced by the network’s variety department instead of its sports wing. Response within NJPW was mixed, as Inoki was surprisingly supportive, but Seiji Sakaguchi opposed it. Meanwhile, Weekly Pro Wrestling reporter Fumihiko “Fumi” Saito was brought on as a writer and filter for the variety department’s ideas. I Can’t Wait Until The Give Up!! didn’t try to ease old fans into the new format. Kuniko Yamada and Kenichi Nagira were hosts, and other entertainers include idols LaSalle Ishii, Togumi Otoko and Kaoru Shimura, as well as actor and wrestling fan Reo Morimoto. The show was set up so that such celebrities could play to a studio audience and provide guest commentary on the wrestling. Segments in the premiere promoted Bam Bam Bigelow with a promo video and a segment comparing his weight to that of audience members, while Masa Saito entered the studio to challenge Inoki. All the while, though, the camera crew favored the celebrities in their close-ups. The backlash was immediate, as a dismal 5.7% debut fell to a 5.0% the next week. The studio and idol elements were soon dropped in favor of studio interview segments. It was after this change, though, that the most famous incident of the I Can’t Wait Until The Give Up!! experiment took place. Yamada interviewed Hiroshi Hase, a Japan Pro Wrestling recruit who had completed his debut excursion but had not yet debuted for NJPW. Kuniko asked a dumb question about whether a bleeding wrestler ceased to bleed when they returned to the waiting room (if I’m parsing it correctly, it seems to imply that she thought they used fake blood), and an agitated Hase snapped at her. While the likes of Inoki and Tatsumi Fujinami understood the difficulty of Yamada’s position, and they sympathized as her awareness of viewer backlash took a toll on her well-being, many others must have felt that Hase had spoken for them in that moment. In July, the studio element was dropped and other planned variety show segments were shelved. However, this experiment would reverberate in the company for years. When Beat Takeshi returned to TV Asahi, he got involved with NJPW as the head of a faction which played off of the Corps, Takeshi Puroresu Gundan. And while one member of that group, Leon White, had been scouted by New Japan before the I Can’t Wait Until The Give Up!! experiment, the Vader gimmick and helmet prop, were vestiges of an idea from that period to create a gimmick that would appeal to shonen fans. (For those unaware, the Vader costume was a Go Nagai commission.) While his debut came months after I Can't Wait Until The Give-Up! had been abandoned, Big Van Vader was partially its offspring.

-

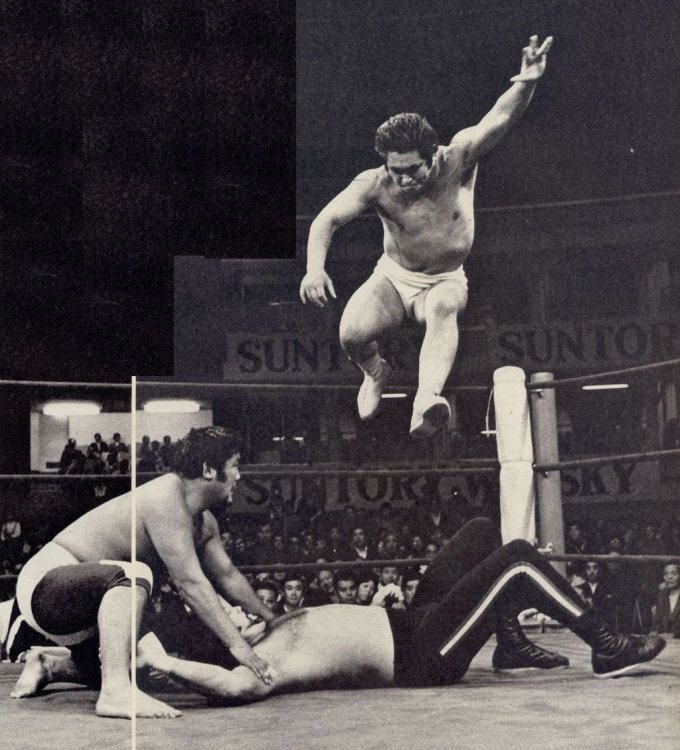

This spread from the 1981 Jumbo Tsuruta Pro Wrestling Album shows Tsuruta performing at the Ruido. .

-

The following is translated from a column in the March 1978 issue of Monthly Puroresu. Charity concert featuring Tsuruta and other vocalists Whenever he had free time during his regional tours, he would visit nursing homes and other places of comfort. Despite his appearance, Jumbo Tsuruta has a strong spirit of volunteerism. On March 1, he will hold a charity concert at the "Ruido" restaurant in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Last September, Tsuruta held a "Songs for Young People" charity concert. This will be the second time he has held such an event, but this time it will not be just for his friends. This time, he would like to invite professional singers and hold a joint concert with them. Of course, when he says "invite professional singers as guests", he doesn't mean popular celebrities such as Mr. Hiroshi Itsuki, Ms. Yoshiko or Ms. Momoe [Yamaguchi]. When he says, "I can only sing folk songs, and I would like a folk singer as a guest singer," it seems that he has been considering Sakura Kono, who is a longtime fan of Tsuruta himself and also sings folk songs. He also said that he would like Baba to sing a song at the event, and all the young wrestlers of All Japan Pro, including Onita and Sonoda, are scheduled to appear on stage. About 20 disabled boy fans will be invited to the event, and they will sing for about two hours, so please cheer them on, dear readers.

-

KinchStalker's Puroresu History Thread Leftover Posts

KinchStalker replied to MoS's topic in Pro Wrestling

I think we're fine. These are all inessential overall. -

Korakuen Hall Capacity: 2,005* Background Completed in 1962, the Korakuen Bowling Hall opened a Korakuen Gymnasium on its fifth and sixth floors. It was Japan’s first such venue without windows. In 1967, it was renamed Korakuen Hall; the bowling alley was moved and replaced with a roller rink six years later. The exterior has been remodeled four times, most recently after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake. The venue continues to see regular use for combat sports, and the fact that Korakuen provides its own ring is an attractive one to boxing promoters. It also serves as a dance hall, as its floorboards meet the specifications for competitive dance. After the construction of JCB Hall in 2008, the Tokyo Dome Corporation lowered Korakuen’s rental fee. Wrestling Korakuen held its first wrestling show on November 25, 1966, with Giant Baba defeating Luis Hernandez. Besides an April 1970 show by the IWE, the JWA sabotaged its competitors’ attempts to run the building, until AJPW booked it in November 1972. After the JWA’s collapse, Korakuen opened up to all of puroresu, including AJW. In the late 1980s, Weekly Pro Wrestling editor and Baba creative consultant Tarzan Yamamoto put Korakuen at the center of his strategy to revitalize All Japan. The quality of AJPW’s Korakuen shows in this era, best represented by the 1991 Fan Appreciation Day event and its revered Super Generation Army/Tsurutagun six-man tag, were foundational to the venue’s modern mythos. As it has become more affordable for indies to run, the consistency and attendance of a company’s Korakuen shows are often gauged as a shorthand for their current status. *AJPW frequently announced capacity crowds of 2,100 in the early 90s. However, claimed attendance figures from previous years go as high as 3,400, such as All Japan’s January 18, 1981 show featuring Baba’s 3000th match against Verne Gagne.

-

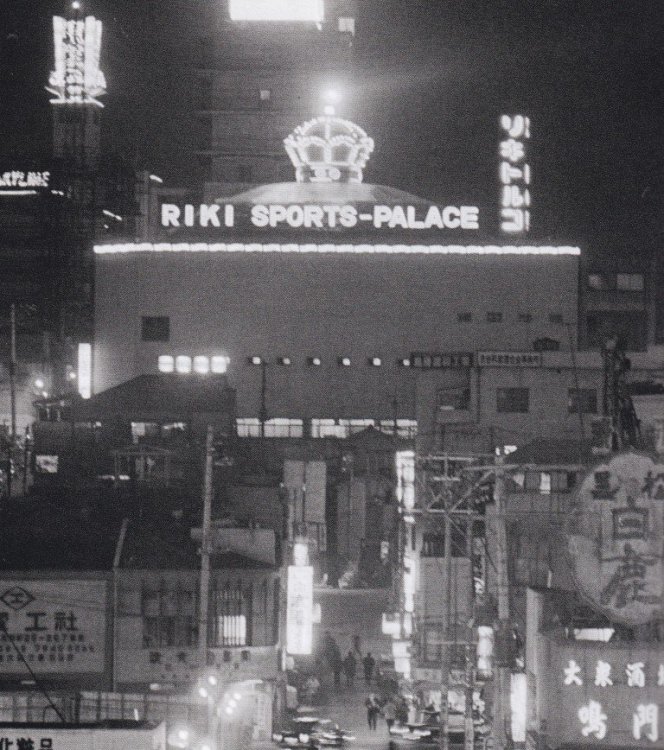

Riki Sports Palace Capacity: 3,000 Background The Riki Sports Palace wasn’t the first venue Rikidōzan built; the Rikidozan Dojo/Japan Pro Wrestling Center predated it by several years. As the Dojo became eyed for public appropriation, though, Rikidozan decided to build a larger venue in Shibuya. It would be a permanent home for pro wrestling: the Kuramae of puroresu. Modeled after the Honolulu Civic Auditorium, Rikidozan spent 1.5 billion yen to build the Riki Sports Palace, which was completed in 1961. On some level, the Palace was a practical investment, as it gave the JWA a consistent base in Tokyo while eliminating the need to rent a venue in the market. Unfortunately, the Palace bloated into a symbol of its namesake’s hubris and poor business acumen, from offices and dojos to a sauna and a bowling alley. After Rikidozan’s death, the Palace became an albatross around the JWA’s neck in the eyes of an executive council that sought to cut ties with the debt-ridden Riki Enterprises. While sales manager Isao Yoshihara attempted to buy it from Riki Enterprises, Kokichi Endo sabotaged this. As Yoshiwara left to eventually form the IWE, the Palace was seized as collateral by its creditor. After spending much of its life as a cabaret theater, the former Palace was demolished in 1992; its atrium and the piping that had been installed for its sauna made it impossible to convert into an office building. Wrestling The Riki Sports Palace was regularly used by the JWA for five years. The Palace held its final show on September 23, 1966.

-

Kuramae Kokugikan Capacity: 12,000 Background With the Ryogoku Kokugikan closed off to them, the Sumo Association began the construction of a new venue in 1949, on a plot of land they had purchased in 1941. While the Kuramae Kokugikan was officially completed in September 1954, it was used for sumo as early as 1950, and in fact its earliest brush with pro wrestling predates its completion. Plans were made to rebuild Kuramae to double capacity in the mid-sixties, but they were abandoned as sumo’s popularity declined. The venue was closed in 1984, with a sale to the Tokyo city government helping fund the construction of its successor, the second Ryogoku Kokugikan. It is now used as an office by the city sewage department. Wrestling From Rikidozan and Masahiko Kimura’s first battles with the Sharpe Brothers in February 1954, to Inoki vs. Choshu in August 1984, the Kuramae Kokugikan might have more history with mens’ puroresu than any building in the country, standing or otherwise. There are so many that rattling off even a few would be silly, but suffice it to say that, if you were promoting a big match in Tokyo, especially in the last decade or so before its decommissioning, and if you could work it around the sumo schedule , it was quite likely that you were going to book Kuramae. Unlike the modern Ryogoku Kokugikan, which uses an elevator system to retract the sumo ring when not in use, Kuramae forced wrestling and boxing events to set their rings directly atop the dohyō. This provided a unique opportunity for heels, who could grab and weaponize the sand and soil below them; it also made scheduling a show tricky, because the dohyō needed a week to be filled and hardened back up after a wrestling event. Unfortunately, it also prevented joshi promotions from booking Kuramae, due to the Sumo Association’s policy banning women from stepping onto the sumo ring. While Mildred Burke had been allowed to run the venue back in 1954, this courtesy was apparently not extended to her Japanese successors. For this reason, Kuramae shows also didn’t feature bouquet girls (or so I've read it claimed; I have seen contradictory examples).

-

Denen Coliseum Capacity: 10,000 Background Opening in 1936, Denen Coliseum was an outdoor venue associated with the Denen tennis club; to commemorate its opening, Bill Tilden came to play a match. From hosting the Davis Cup in 1955 to a decade hosting the Japan Open Tennis Championship, the Coliseum was used for its original purpose for many years. Over time, though, it would also become notable as a music and wrestling venue. Denen closed in 1989 amidst housing development plans, having been functionally replaced by the Ariake Coliseum. Wrestling Denen and wrestling went back to 1956, when Rikidozan defended the fictitious Pacific Coast title against Tom Rice on September 1. Three years later, he defended his International Heavyweight title in a World League final rematch against Mr. Atomic. The brainchild of sales manager Hiroshi Iwata, the masked Mr. Atomic was specifically designed to target a younger audience, as a response to the beginnings of tokusatsu television with Gekko Kamen. As attendee Kosuke Takeuchi recalled, a ticket to the Denen show cost just fifty yen for children. As far as puroresu is concerned, though, Denen is far more famous for a series of matches and moments from the late 70s through the early 80s. The first of these was Jumbo Tsuruta’s NWA United National title defense against Mil Mascaras, on August 25, 1977. The “idol showdown”, as it was known, remains one of AJPW’s most iconic early matches. Denen even saw a sequel of sorts, as Baba & Jumbo defended their NWA International Tag Team titles against Mascaras & Dos Caras on August 24, 1978. On September 23, 1981, NJPW treated Denen to Stan Hansen’s final singles match against Andre the Giant, commonly considered one of the greatest foreigner vs foreigner matches in puro history. That same show saw the beginning of the Kokusai Ketsumeigun invader angle, as ex-IWE stars Rusher Kimura and Animal Hamaguchi hit the ring to declare war. Other notable incidents include Tsuruta’s May 22, 1984 NWA title challenge against Kerry von Erich, and Mitsuharu Misawa’s debut as the second iteration of Tiger Mask three months later.

-

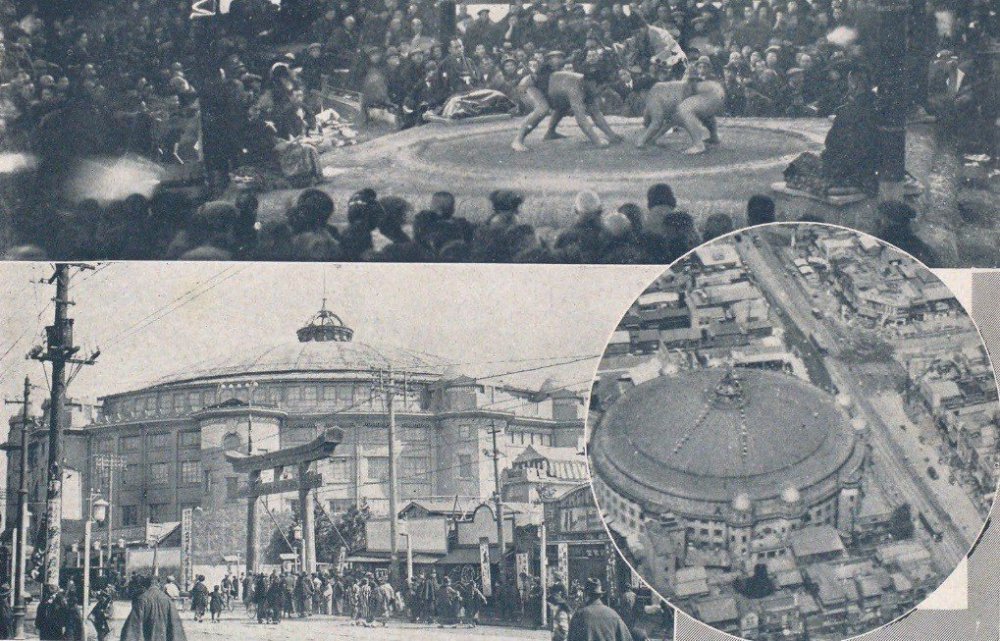

Ryogoku Kokugikan/Nihon University Auditorium Capacity: 10,000 Background After three years of construction, the Ryogoku Kokugikan was completed in the spring of 1909. Designed by architect Tatsuno Kingo, its neo-Baroque influences were in keeping with Kingo’s other major works, such as the Bank of Japan and Tokyo Station. The Kokugikan would be rebuilt twice due to fires in 1917 and 1923. In 1944, the venue was seized by the Imperial Japanese Army and converted into a balloon bomb factory. After the Kokugikan was heavily damaged by the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 1945, the sumo association was allowed to hold their June tournament there, albeit as a private event for wounded soldiers. Seized once again by the occupational authorities in October 1945, the Kokugikan was renovated. The following November, the Kokugikan held its final sumo tournament. By the time the occupation ended, the Kuramae Kokugikan was already in use and since there was no room to install parking lots in Ryogoku, the sumo association sold it to Kokusai Stadium in 1952. Six years later, it was acquired by Nihon University and renamed as its auditorium. It would remain in use until revisions in building code took effect in the late 1970s, as its roof was deemed too old to support a sprinkler system. The building was officially closed in 1982 and dismantled the following year, after further revisions made sprinkler systems mandatory for large venues. Wrestling The Torii Oasis Shriners Club tour of 1951, generally (if reductively) considered the start of puroresu, began with a show in the Kokugikan on September 30. One month later, it ran the venue again, featuring the debut of Rikidozan. While the Kokusai Stadium period saw the company install a roller rink, the Kokugikan saw continued use for wrestling and boxing events, and this would persist into Nihon University’s ownership. At some point Nippon Television acquired exclusive rights to run the venue, and its last wrestling events were all AJPW shows. Most notably, the Auditorium held the December 5, 1974 show on which Giant Baba defeated Jack Brisco to win the NWA World Heavyweight title.

-

Tokyo The capital of Japan, and the capital of puroresu, Tokyo is one of wrestling’s greatest cities. This thread will explore its rich history through profiles of its major wrestling venues across the decades. Major Venues Ryogoku Kokugikan/Nihon University Auditorium (1909-1982) Denen Coliseum (1936-1989) Kuramae Kokugikan (1950-1984) Riki Sports Palace (1961-1966) Korakuen Hall (1962-) Nippon Budokan (1964-) Ryogoku Kokugikan [II] (1985-) Tokyo Dome (1988-) Differ Ariake (2000-2018)

-

Masio Koma (マシオ駒) Real name: Hideo Koma (駒秀雄) Professional names: Hideo Koma, Atsuhide Koma, Kakutaro Koma, Mr. Koma, Masio Koma Life: 5/18/1940-3/10/1976 Born: Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan Career: 1961-1976 Promotions: Japan Wrestling Association, All Japan Pro Wrestling Height/Weight: 172cm/100kg (5’8”/220 lbs.) Signature Moves: Dropkick Titles: NWA World Middleweight [EMLL] (1x), NWA United States Tag Team [Gulf Coast Championship Wrestling] (2x, with the Great Ota/Gantetsu Matsuoka), NWA Western States Tag Team [Western States Sports] (2x, with Mr. Okuma/Motoshi Okuma) As a wrestler, Masio Koma has a humble legacy marked by some territorial success. However, he was an important figure in AJPW's early years, and his unexpected death is regarded by colleagues and journalists as a turning point in company history. Hideo Koma's athletic background was in baseball, which he played through high school as a teammate of Sadaharu Oh. Upon his graduation, Koma joined the JWA in June 1961. Debuting on October 11 with a loss to Mitsu Hirai, Koma would become Giant Baba's first valet. Like his successor Motoshi Okuma, Koma would remain loyal to Baba for the rest of his life. Hideo's early years would see him booked under his real name, and then as Atsuhide and Kakutaro Koma. In January 1970, Koma embarked on a pioneering excursion to EMLL. On August 28, he became the first Japanese wrestler to win Mexican gold, defeating El Solitario for the NWA World Middleweight title. Koma even won it as a technico! In a 2008 web column, journalist and lucha expert Tsutomu “Tomas” Shimizu (AKA Dr. Lucha) claimed that Mexican fans of a certain generation were as likely to name Koma as the greatest Japanese foreigner to wrestle in Mexico as they were Sayama. Two years later, Shimizu would rank Koma as the fourth greatest “Japanese luchador” (based on their Mexican runs, not necessarily as "lucharesu" wrestlers), behind Ultimo, Sayama, and Hamada at #1. After this, Koma traveled north to begin work as a US territorial heel, teaming with his peers Okuma and Gantetsu Matsuoka to tag success in the Florida and Amarillo territories. It was during his run in the latter that he and Okuma were recruited by Baba for All Japan Pro Wrestling. Koma has been cited in multiple narratives as the crucial man in getting Dory Funk Sr. to agree to a partnership with Baba. Koma became the first head coach of the AJPW dojo. Deeply respected by Baba, enough so that he could comfortably raise objections to him, Koma was also assigned as the handler of Jumbo Tsuruta. Alongside Sato, Koma gave Tsuruta about four months of part-time instruction as Tsuruta completed his baccalaureate. Koma would also teach Tsuruta locker room etiquette and acted as a buffer between Tsuruta and the resentment of his peers. Koma would successfully produce three wrestlers: Atsushi Onita, Masanobu Fuchi, and Kazuharu Sonoda. He was also involved in training Kyohei Wada. However, his poor health led AJPW to hire US-based wrestler and former IWE trainer Matty Suzuki as a wrestler and coach for extended periods in 1974 and 1975. Koma died of liver failure in 1976. Koma's training methods were reformed by Akio Sato in the early 1980s, as Nippon Television ordered the company to begin producing more native talent. The story of Naoki Takano, a pre-Sato graduate (and cousin of George and Shunji) whose career ended in a horrific training injury just months after his debut, suggests that such reforms were warranted. Not everyone agrees, though. The Great Kabuki has claimed that Koma's death "ruined" All Japan. Koma had incorporated "gachinko" (Japanese term for shoot) fundamentals into the curriculum. Not only did AJPW fail to produce a homegrown wrestler from Sonoda's 1975 debut until Shiro Koshinaka's graduation in 1979, but the gachinko tradition was lost in favor of an Americanized, "passive" house style influenced more by the Funks than by puroresu. Kabuki remarks that "they all became weak". NJPW head trainer Kotetsu Yamamoto had been a good friend of Koma's, and he would later reveal that they consulted each other about their methods. Would Koma have developed his method further had he lived? Would the stylistic gap between AJPW and NJPW have become narrower? Whatever the case, Koma was one of AJPW's most important early figures, and although Great Kojika claims that the company culture became "lighter" after his death. It has also been cited as a destabilizing incident behind the scenes. It may have led Tsuruta to become closer to Samson Kutsuwada, which complicated Jumbo’s relationship with Baba after the 1977 incident.

-

This will either be the final or penultimate post. The final chapter is an examination of the Shitenno's legacy, and I may or may not share some of that stuff. Apologies for the formatting inconsistencies, I have no idea how to resolve them. 2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART SIX There isn’t much that Ichinose brings to the story behind AJPW’s first Dome show. There’s nothing he says that you couldn’t read in Eggshells or contemporaneous Observers. I guess I could bring up that Kobashi had “mixed feelings” about Baba saying that Misawa vs. Kawada was AJPW’s best match in a press conference. Ichinose seems to frame the Halloween 1998 Misawa/Kobashi match as Kobashi’s response to this. Also, it’s made very clear that Baba would never truly put Kawada ahead of Misawa in the pecking order, due to their junior-senior relationship. I’m going to skip the rest of the stuff about the first five months of 1998, since it adds nothing new and I want to get the albatross of this book off of my neck so that I can research other things guilt-free. — Ichinose’s last issue for Weekly Pro was the one covering Kobashi’s Triple Crown victory against Baba. His other great love was baseball, and he would finally get to cover it in a freelance capacity. However, Ichinose intended to maintain his relationship with Baba. This would not last long, though. — Before he came back, Misawa openly criticized his company in the press. He stated that All Japan did not use guest talent effectively and that its treatment of the junior division was poor. Since Misawa had made his critiques public as leverage, this was dubbed the Misawa Revolution. Baba acquiesced. The GET breakup angle at the beginning of the Summer Action Series II tour, wherein Johnny Ace turned on Kobashi after their tag loss to Taue & Tamon Honda, was seen as an immediate refutation of the akuruku part of Baba’s motto. Yoshinari Ogawa’s call-up to Misawa’s new tag partner was a subversion of Baba’s ideal of the “clash of big bodies”. (Ichinose doesn’t mention the Observer-reported story that Misawa’s original choice was the even more radical Masahito Kakihara, which was vetoed.) At some point, Misawa finally figured out that Weekly Pro had been offering creative input, and confronted Wada: “It’s Tarzan, isn’t it?” Now, by the time Misawa learned that Weekly Pro was involved, Tarzan had long since stopped coming to creative meetings. Yamamoto still had good relations with Baba and had since mediated to get Yoshiaki Fujiwara and Don Arakawa to work dates for AJPW, but only Ichinose was still pitching ideas. Fuchi is quoted recalling that Motoko had always asked him what matches he wanted to see on a tour, and that the Weekly Pro involvement had lightened Baba’s load, since he wanted to decide on a tour’s cards as soon as possible and appreciated assistance for provincial shows. Regardless, “Misawa did not want to be moved in a way that was beyond his control.” Ichinose spends the next couple pages quoting Misawa interviews from the past couple years, speculating that his discontentment had begun in 1996. He also contrasts Kawada’s “three-year cycle” theory with Misawa’s beliefs, painting this as another of their myriad differences. Ichinose’s last meeting with Baba was a hotel lunch in September, with Motoko and Wada. Ichinose recalls a quiet Baba, who at one point mused that “in just one or two tours”, Misawa would realize how hard the job really was. (Kawada is critical of Misawa’s skill as a booker, believing it directly hurt AJPW attendance. In his opinion, Fuchi was more qualified for the role, as shown by his central role in putting the Super Generation Army matches together.) Ichinose also reads a sense of bitterness in Baba’s comments on the 10/31 Misawa/Kobashi match. He wonders if Baba may have planned to strike back, and Wada is quoted making a very interesting claim in the 48th issue of G Spirits. “After that, there was a meeting between Baba and Misawa...I still remember that he said, "Don't interfere with my wife at all. I'm the only one who can use the All Japan Pro-Wrestling sign. If you want to do it, you can take over all the offices and training camps, and you can call it 'Misawa Pro-Wrestling'. But I won't let you put up the All Japan sign there." — Baba died on January 31, 1999. Ichinose was in Texas covering the Yakult Swallows training camp when he heard the news. —- Ichinose might not have been covering AJPW anymore, but he still offers some interesting nuggets. According to him, Misawa was intent on bringing Shinya Hashimoto onto the Baba Tokyo Dome show as a surprise opponent for Kawada. Hase was even used as an intermediary. But alas, Motoko put her foot down. Ichinose claims that Jumbo had actually wanted to retire for years, but that Baba insisted he remain as a part-timer. He wasn’t paid full salary, but he still got a living wage. As the company’s financial situation got tighter and bled into production cost cuts on their television program (think of the shitty lighting on some tapings, such as the 1997 Kobashi/Hase match), some among the locker room came to resent Tsuruta for leeching off of their wages. Baba’s tendency to keep most of his wrestlers’ earnings in savings (to be used for, say, a down payment if one were to purchase a house, as Taue recalls) can’t have helped. Much earlier in the book, Ichinose listed a revealing amount of earnings by various wrestlers, as was revealed when the SWS guys tried to take Baba to court. In the fiscal year beginning April 1, 1989, Tenryu received ¥2,355,000, while Yatsu got ¥1,628,000 and Kabuki got ¥1,332,000. Compare this to Goro Tsurumi, who always stayed freelance and received ¥7,352,000. Meanwhile, top prospects such as Shunji Takano and Isao Takagi made 6.1 and 4.4 million yen that year, while the likes of Fuyuki and Nakano made less than ¥750,000. (Remember, Tenryu tried to negotiate higher wages for his juniors when his contract renewal had come up.) Ichinose tempered that by adding that AJPW alumni would express gratitude for the pensions they were provided, but one can easily see how this setting would breed resentment in leaner times, and why Misawa wanted to modernize the contracts. — A decade later, Ichinose got a call from Motoko. Mitsuharu Misawa had died.

-

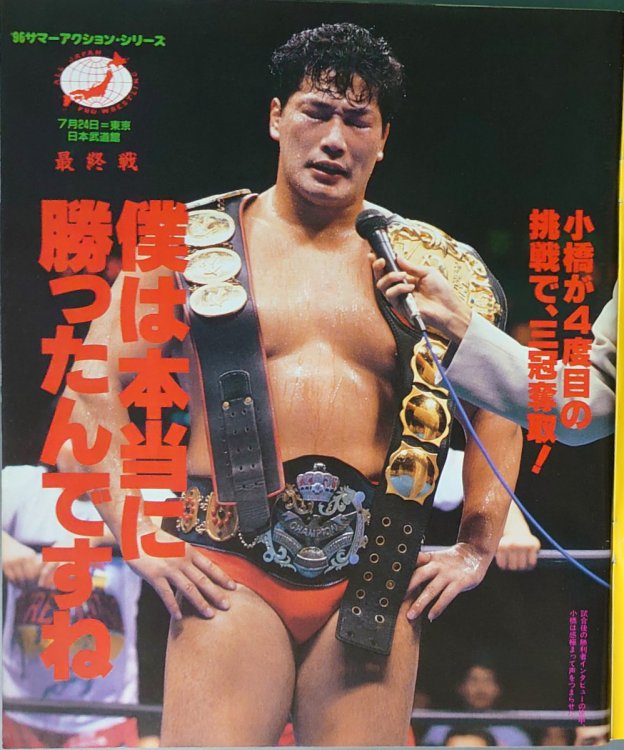

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 25-31, PART FIVE The youngest of the Shitenno finally wins the Triple Crown. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling issue #747, dated August 13, 1996 (taken from Twitter post)] On May 24, 1996, Taue ended Misawa’s second Triple Crown reign in Sapporo. Underneath, Kobashi and Kawada wrestled for the #1 contendership, and Kawada won. This was the first proper #1 contendership match Kobashi had wrestled since that famous Steve Williams match in 1993, although he had taken part in the contendership league tournament in the summer of 1995.. With the Williams match, there had been a sense of accomplishment that transcended his defeat, as Kobashi dragged himself to the foreign locker room to shake Dr. Death’s hand. This time, there was none of that, as Kobashi disappeared without giving a word to the reporters. Kobashi began to use the lariat in the summer of 1996, having acknowledged that he needed to use the moonsault more sparingly and reasoning that he had bigger arms than Hansen. He debuted the move on July 5, in an Osaka six-man tag with Misawa & Akiyama against Steve Williams, Johnny Ace & the Patriot, defeating the Patriot with it. However, he claims he originally thought to use the move as “a honeycomb”, not a finish. (Looking at purolove results, though, he did use it as a finish regularly on the tour. Besides the aforementioned six-man, he got pinfalls in tag matches against Yoshinari Ogawa and Johnny Smith with the move, and used it to win singles matches against Giant Kimala II and Tamon Honda.) When they ran Korakuen Hall on July 20, Joe Higuchi called Kobashi into the foreign locker room. Hansen advised Kobashi to use the lariat as a killshot move. At tour’s end, in the Budokan on July 24, Kobashi got his title shot, and he made the most of it. The lariat didn’t end up being the killshot, but it gave Kobashi enough time to climb the ropes to hit a diving guillotine drop for the pinfall. When asked to give a comment to the fans, Kobashi closed his eyes and let his lips tremble: “I’d like to work with all of you to make this belt even greater.” On September 5, he defeated Hansen in the latter’s final singles title shot, with his lariat symbolically surpassing the Western Lariat. — The famous apron powerbomb counter from the January 20, 1997 Triple Crown match. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling issue #777, dated February 11, 1997 (included in free preview of archived digital copy)] Ichinose devotes a good page or two to press comments building up to Kobashi’s Triple Crown defense against Misawa on January 20, 1997. Misawa spoke of having a fight that only the two of them could understand, which evoked his comments leading into their first Triple Crown match against each other, on October 15, 1995. Every move would count, but he didn’t want to wrestle deliberately; he wanted to wrestle with “all of his heart”. Misawa wanted to be better this time than the last, and to be better next time than this time. Ichinose mentions Akiyama’s comments on the previous tour, the 1996 RWTL. In AJPW’s continuing effort to cater to provincial markets, Baba cut the number of entrants from ten teams to seven. To compensate, each team wrestled each other twice in an extended round-robin. Akiyama remarked that this was the kind of arrangement that shortened careers. Again, Ichinose’s metaphor of the All Japan bus and its worn Shitenno tires comes to mind. All Japan was in a deadlock, and Kobashi spoke of the 1/20 match as “a battle to change All Japan”. When Akiyama’s comments were referenced in the interview, Misawa embraced the escalation, saying that “you can’t wrestle if you think about the future”. For what it’s worth, Kobashi claimed in a later interview that his comments in the late 90s and early 2000s, and perhaps Misawa’s as well, had partially been a response to MMA: an implicit attempt to legitimize pro wrestling through how much of themselves they put in the ring. Ichinose frames the match itself as reflecting a battle along these lines, citing Kobashi’s armwork approach as an unusually pragmatic measure, while justifying Misawa’s continued use of the worked arm (as well as the famous apron powerbomb hurricanrana counter spot) as reflecting his elevated disregard for survival. Misawa was too exhausted after the match to even take back his belts, disappearing down the aisle on Satoru Asako’s shoulders “as if he had lost”. When just out of sight of the audience, he collapsed. While Misawa would speak to the press, the lack of the customary toast reflected an atmosphere “unsuitable for alcohol”. Ichinose quotes Misawa’s strained comments: “Kobashi said he wants to change the history of All Japan by winning this match. I'm more of a doer than a talker. Because I'm the kind of person who can't say what I'm going to do. [...] It's a good way to make it easier for the young guys. I want to make it easier for the young guys so that they can feel that if they work hard, they can be like me.” — Ichinose covers contemporaneous press comments that expressed Kawada’s apparent dissatisfaction with AJPW. By this point, as Ichinose puts it, the Misawa-Kawada feud had become a Möbius strip, and Kawada’s comments leading up to it saw him implicitly acknowledge the wall he had hit; even if he won, it was “a journey that would never end”. He also jumps back a bit later on to reference Kawada’s comments on Misawa and Kobashi’s January 1997 match, which he said was “not great in terms of pro-wrestling” before giving a backhanded compliments that the match was great anyway because “two big guys were doing it”. (Misawa did not appreciate these remarks.) Kawada’s recollection of his thoughts after the March 30 show, on which Kobashi pinned Misawa in a Carnival match, also suggests that he felt passed by: “just when I thought I was finally going to surpass Misawa, Kobashi did it first.” On the topic of wrestling for other organizations, Kawada said that he was happy to have his name mentioned by anyone, and was willing to fight anyone, but that “what was impossible was impossible”. Genichiro Tenryu stated around this time that he wanted to wrestle Kawada to mark the coming tenth anniversary of Revolution. You can guess how far that went. Ichinose also mentions Kawada’s use of a vertical drop DDT and triangle choke in the June 6 Triple Crown match. The previous night, NJPW had run the Budokan with Shinya Hashimoto retaining the IWGP Heavyweight title against Keiji Mutoh. As Ichinose writes: “While running in the Mobius circle of overcoming Misawa, Kawada's consciousness was more or less focused on New Japan. Was it a rivalry with the Three Musketeers of the Fighting Spirit? Or was it a silent encouragement to the men of his generation?” This transitions into some comments on the Pillars and Musketeers. As the only one to have wrestled all three Musketeers in a singles context, Kawada’s comments are first. He felt that Mutoh “was good at what he did”, but said that in his opinion, putting things together well or doing things in a certain way was not the same thing as being good. (A bit later on, Taue is quoted commenting on Mutoh’s selfishness as a performer: “He's going to do what he wants to do, and then he's going to come home. I did a lot of work on him before, and he was tired, and I told him not to come home yet, but he forced himself on me.”) Kawada was not impressed by Hashimoto’s toughness when they wrestled, but he acknowledges that Hash wasn’t in great shape at that point. As for Chono, whose ring shoes “should have been illegal”, he didn’t move fluidly. Katsuhiko Kanazawa, who was Weekly Gong’s reporter for New Japan during the heyday of the Musketeers, is quoted recalling the Musketeers’ stray thoughts on the Pillars: “I think they were pretty negative about it at the time.” Hashimoto expressed reservations about the escalatory nature of Shitenno puroresu: “Even if you drop him on his head, the match doesn’t end.” Mutoh was fixated on Misawa, wondering how he could wear green tights and if “[Misawa] thought he should not be compared to him”. He was also concerned about Kobashi’s use of the moonsault as early as Kobashi’s time teaming with Johnny Ace in the early 90s, asking Kanazawa to advise him not to use the moonsault so much and lighten the burden on his knee. When Kanazawa relayed this, Kobashi appreciated the concern but remarked that his knee was already ruined. Kanazawa also recalls that, interestingly, Choshu thought Kobashi was closer to his ideal wrestler than any of the Musketeers. That didn’t mean that he wasn’t strongly critical of him, though. Choshu wanted him to ditch the orange tights, stop clenching his fist and making faces, and drop the lariat, as “it didn’t suit him”. — On the October Giant Series tour, Misawa defended the Triple Crown twice: first against Steve Williams, then against Kobashi at the 25th anniversary Budokan show on the 21st. At the year-end AJPW TV episode, in which the Shitenno sat and ate chanko in a roundtable chat, Misawa let it slip that he had been “forced” to defend it twice, before trying to walk that back. Ichinose punctures a pervasive myth about the latter match. In the climax, announcer Shigeko Kaneko claimed that his broadcast partner, Baba himself, was crying. This built a legend over the years, and the incident is sometimes cited as a moment where Baba felt the AJPW style had gone too far. However, Ichinose was there as well, and while he could understand why Kaneko might have mistaken Baba’s glistening face for the marks of crying, he insists that Baba was not actually in tears, and Baba’s comments in fact displayed pride in the match. After the match, though, Misawa claimed that his memory of the match that he had just wrestled was about as good as his memory of their January match. While 1997 was a career year for Misawa, at least from a kayfabe perspective, he would not win Wrestler of the Year from Tokyo Sports. The ¥100,000,000 that NJPW had made in nWo shirts was a decisive factor in Chono’s win.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling