-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

I have the next installment of my IWE History series just about done, but I have a question that's got me stumped and I want to field it by you guys before I put out the post. Does anybody know the name of the original second Cuban Assassin, who teamed with the other one (Ángel Acevedo) in the 70s? They had a two-month reign with the Stampede International Tag Team titles, but most of what I can find about this guy starts and stops with the gimmick name. His Showa Puroresu minibio renders his real name in katakana, but I'm ashamed to admit that I cannot parse what his surname is supposed to be. Frank "Seabranson"? (And no, it's not the David Canal/Fidel Sierra version of the Cuban Assassin who worked in WCW and NJPW.) -

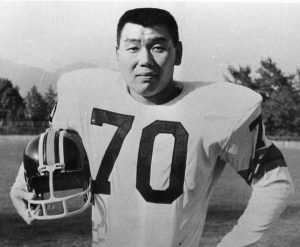

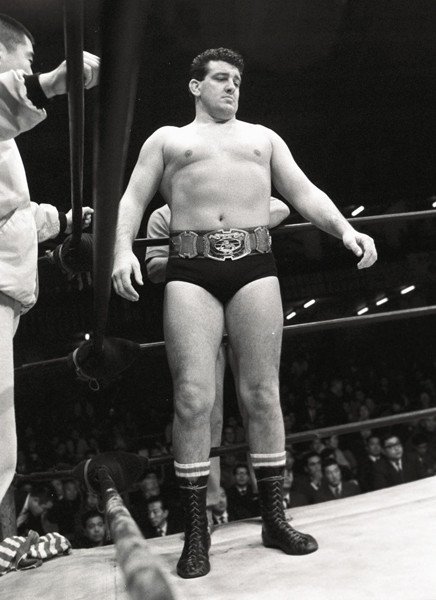

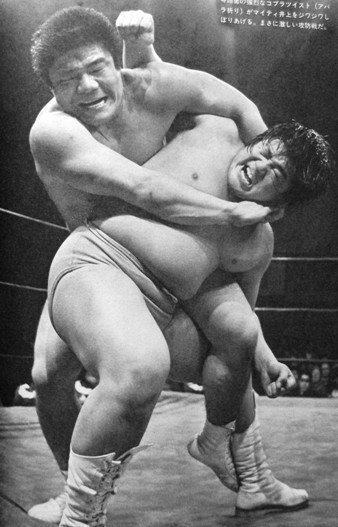

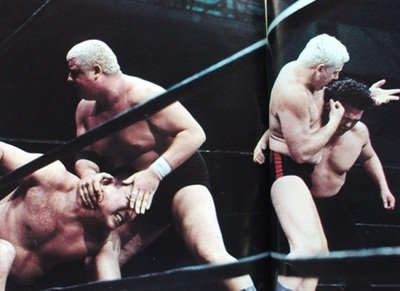

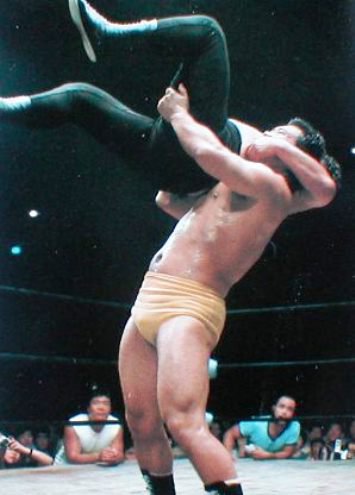

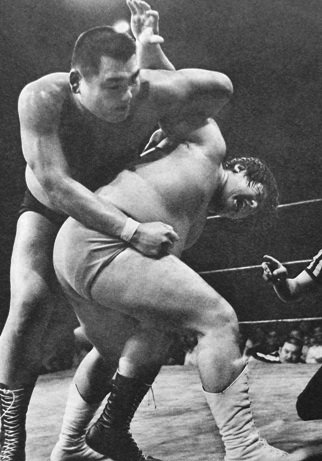

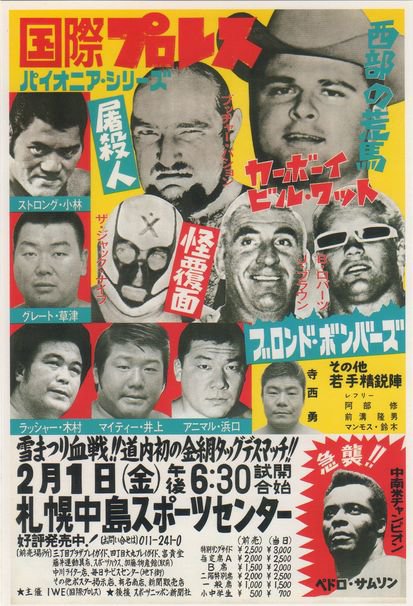

This is the first part that is going to end during a year. The IWE’s TBS coverage ends in early 1974, and that on top of the departure which caused it makes me think it’s best to delineate the two eras of the promotion that way. Part 4 will be about the early years of the Tokyo 12 Channel era. A HISTORY OF THE INTERNATIONAL WRESTLING ENTERPRISE PART 3.2 (1973-1974) [Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3.1 here.] ------------------ 1973, PART ONE Above: Isamu Teranishi and Mighty Inoue wrestle in a rare native vs. native semi-main event on the last show of the Challenge Series. 1973 CONTINUES Left: the Texas Outlaws take it to the IWA World Tag Team champions. Right: Strong Kobayashi lifts Rusher Kimura for a backdrop, in puroresu's first native vs. native title match since 1955. THE 5TH IWA WORLD SERIES Above: the Great Kusatsu and Mighty Inoue square off in a block match in the IWA World Series. THE PEOPLE KNOW IT’S WINTER, (BIG) WINTER IN KOKUSAI Above: two posters for the last show of the 1974 New Year Pioneer Series. KOBAYASHI, ADIEU

-

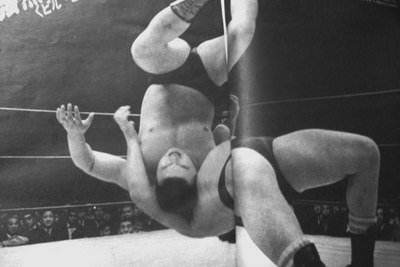

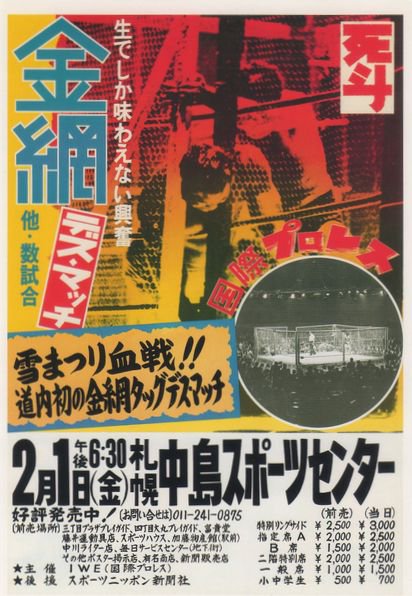

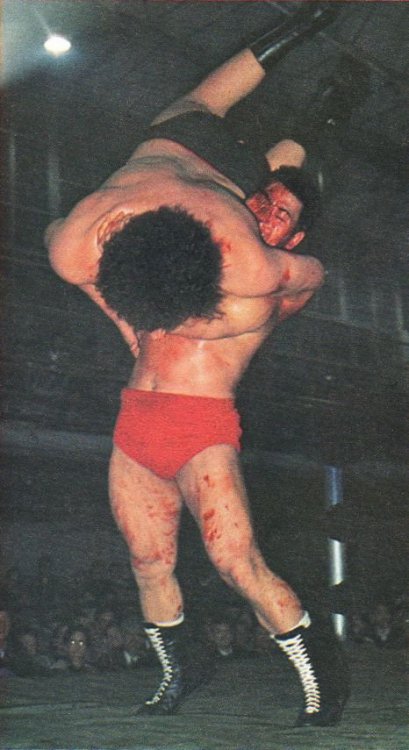

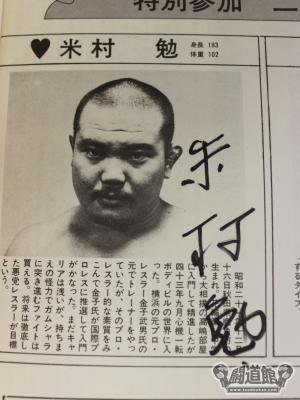

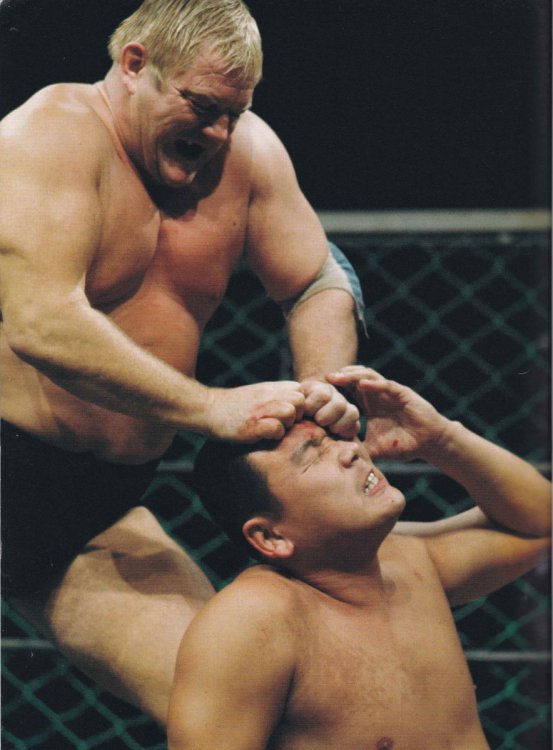

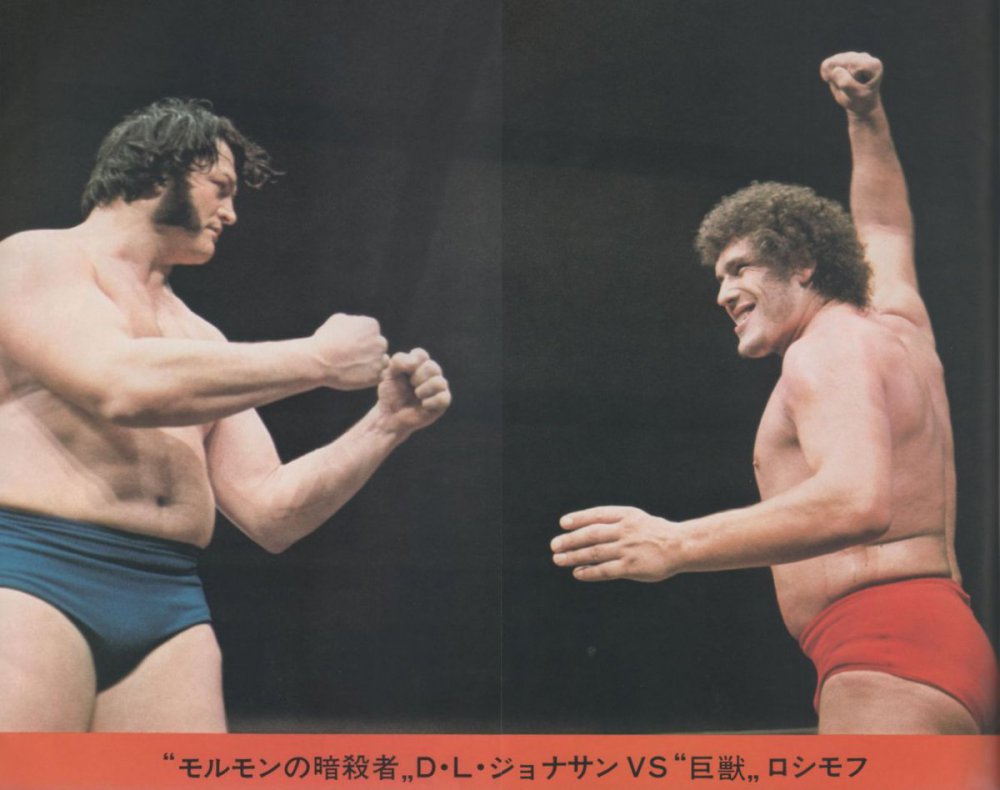

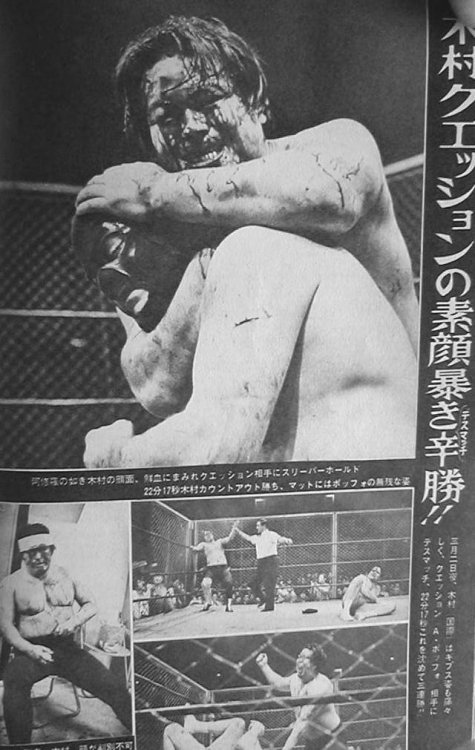

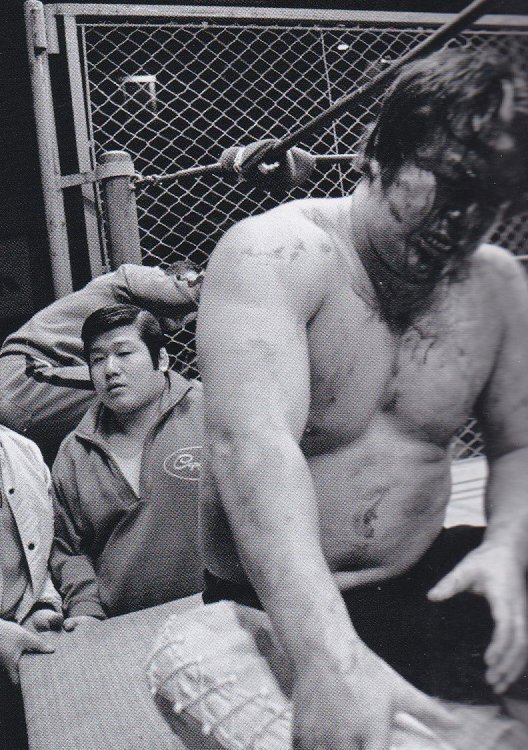

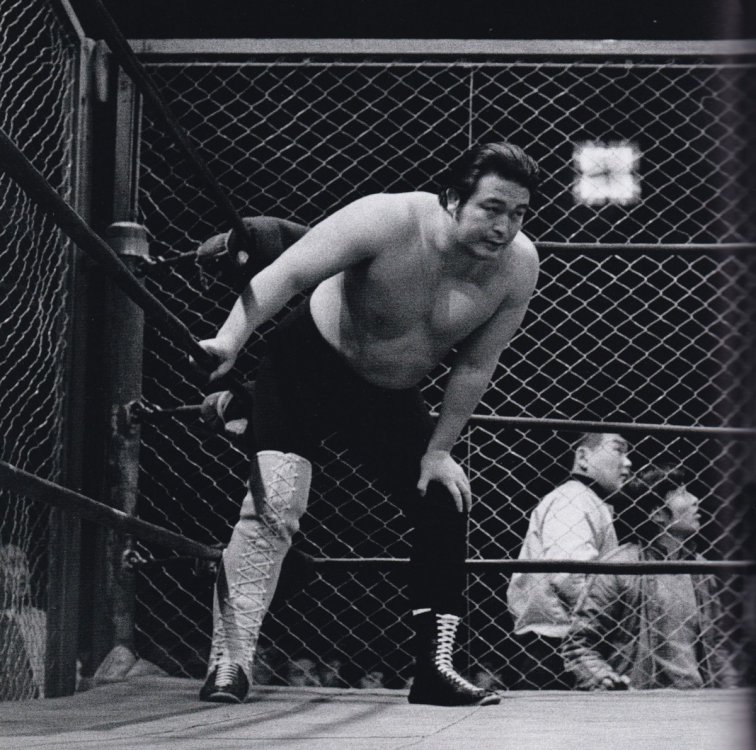

Brothers, I think it’s best to break from my three-years-per-section format from here on out. 1972 alone has gone over 3,000 words, and I feel like putting so much together in batches might be affecting the digestibility of the content. This is a forum thread, after all. A HISTORY OF THE INTERNATIONAL WRESTLING ENTERPRISE PART 3.1(1972) ------------------ 1972 BEGINS 4TH IWA WORLD SERIES Above: Don Leo Jonathan and Monster Roussimoff size each other up in the IWA World Series on 1972.04.24, and Strong Kobayashi bodyslams Monster Roussimoff (presumed date 1972.05.06). 1972 CONTINUED Above: new IWE faces Tsutomu Yonemura (left, from a 1972 IWE tour pamphlet), and Hiroshi Yagi (right image, on the right besides Goro Tsurumi, from the 1973 AJPW New Year Giant Series pamphlet). BRUISER AND CRUSHER Above: Dick the Bruiser brutalizes the Great Kusatsu in a wire mesh deathmatch for the WWA tag titles (1972.11.27)

-

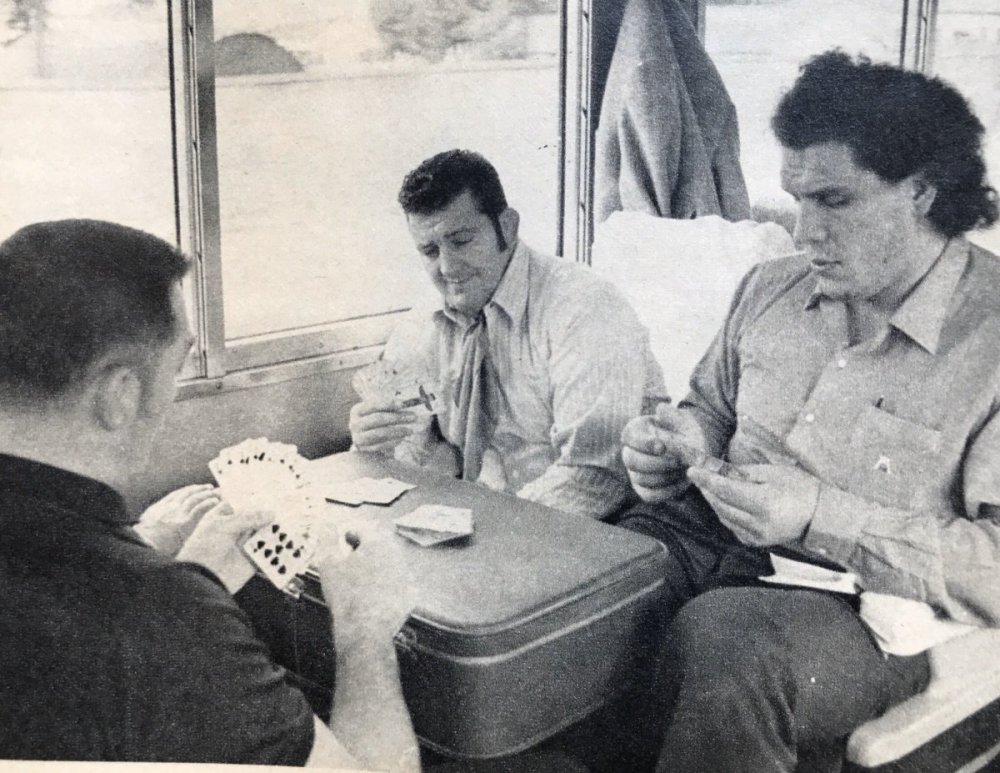

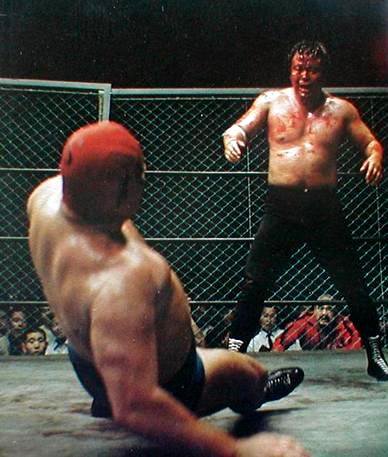

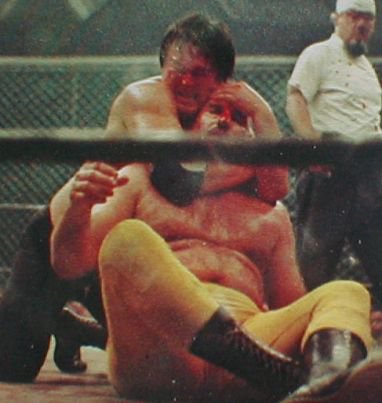

A HISTORY OF THE INTERNATIONAL WRESTLING ENTERPRISE PART TWO (1969-1971) [Read Part One here.] ------------------ CANADIAN CONNECTION AND JAPAN’S FIRST “DEATHMATCH” THE BIRTH OF THE IWA WORLD TAG TEAM TITLES Above: the IWE office receives news of the IWA tag title match's result. CHATI YOKOUCHI Above: Chati Yokouchi crosschops Buddy Colt (unknown date). GAGNE, THE GIANT, AND THE ASCENDANCY OF THUNDER SUGIYAMA Above: Verne Gagne feeds some pigeons during his first trip for the IWE. ANATA GA PUROMŌTĀ AND THE BIRTH OF THE WIRE MESH DEATHMATCH Above: Rusher Kimura is bloodied by Dr. Death (Moose Morowski) in a tag match building up to the IWE's first cage match (autumn 1970). 1971 BEGINS Above: despite not having fully healed his broken leg, Rusher Kimura returned for a crucial Tokyo show on this tour to defeat and unmask the ? (Angelo Poffo) in a wire mesh deathmatch on 1971.03.02. Afterwards, he needed to be carried out on a tatami mat. 3rd IWA WORLD SERIES (OR, HOW GOTCH GOT HIS GROOVE BACK) Above: Karl Gotch, Billy Robinson, and Monster Roussimoff play a game of cards on the IWE tour bus. (This crop of the photo cuts him out, but Magner Clement is also playing to Gotch's left.) THE ACE RETURNS --------------- A lot of this was more tour-by-tour skimming than I’d like; if I ever transcribe that IWE book I’m sure I will find more interesting stuff. But Part Three should be more consistently substantive. It will cover 1972-74, a turbulent period which saw change and turbulence in their television situation, and which also saw them lose the best bet they ever had due to the toxicity of their own inner culture.

-

Just to contextualize the bit with the container: this was booked to be Fuyuki's comeback match before his death, and Kanemura filled in. That container contained Fuyuki's ashes, and both men hurled themselves into the ropes to give him a pair of final symbolic victories. I know the video description has that info but I've always found it a really touching bit.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

I will be covering this in my next IWE history post, but I found a piece of 8mm footage that excited me so much that I had to share it on social media, and I guess you guys deserve to see it too before I complete the post. Behold, the first native heel turn in puro history. Chati Yokouchi had been wrestling for several years, but only worked his native country for two IWE tours in 1969. On the last match of the first tour, a tag with the Great Kusatsu against Gorgeous George Jr. and Buddy Colt, he betrayed his fellow countryman. As we see, Yokouchi turns by walking away from the FIP Kusatsu's outstretched hand, and then gets disqualified for pulling George by the hair over his shoulder. The following tour, Yokouchi would wrestle the native talent in singles and in tags alongside gaijin. Seven years later, Umanosuke Ueda, with whom Yokouchi had tagged extensively during the former's 1968-9 American excursion, returned to Japan with an IWE run apparently influenced by Yokouchi. (As Ueda jumped ship to New Japan he developed a character that puro heels have been cribbing from for decades.) -

There's an Igapro article about Maeda's second stint in New Japan, which addresses that. You know how these Japanese sources are about never totally breaking kayfabe, but nevertheless there's a thread or two that I haven't seen brought up in English-language recounts of the incident. Maeda claims that he tapped Choshu on the shoulder because he expected Choshu to turn towards him to set it up, but Choshu turned the other way instead and bore the brunt of the kick. According to the article, Maeda came up with this spot because he felt that he needed to top Tenryu, who had brutalized Hiroshi Wajima with unprotected kicks in a recent singles match. Inoki and Sakaguchi apparently knew it was an accident, but they suspended Maeda to cool down the situation (this coupled with the accidental Fujinami injury from 1986.06.12 wasn't a good look for him).

-

I think the IWE is worthy of its own extended series, with the excellent Japanese Wikipedia page as a primary source. This will repeat information seen in my previous posts, but I think it’s worth tying it all together into as complete a narrative as I can make without having access to the pair of books on the promotion published by G Spirits in recent years. A HISTORY OF THE INTERNATIONAL WRESTLING ENTERPRISE PART ONE (1966-1968) ------------------ PALACE FORMATION PIONEER PIONEER 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO BATTLE AT THE SUMIDA RIVER INTERNATIONAL LAMPOON: EUROPEAN GAIKOKUJINATION 1968 CONTINUES 1ST IWA WORLD SERIES Part two of this retrospective will likely cover 1969-1971.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

Someone just uploaded an early version of Hashimoto's theme, which I had never heard. It ruuuuuuuules. -

Usually I wouldn’t post again so soon, but I’ve been throwing myself into research to get my mind off of some stuff. So, here’s a rundown on the original Tokyo Pro Wrestling. The bulk of this is sourced from a 2017 Igapro article, which cites issue #47 of the G Spirits magazine as reference material, but there’s also material from the Japanese Wikipedia page for the promotion. Tokyo Pro Wrestling ----------------- In March, I made a post in this thread titled JWA: The Transitional Period. I recommend reading that first if you haven’t, but here’s the essential information: In the aftermath of Rikidōzan’s death, the JWA stuck together partially due to its financial importance to the Japanese criminal underworld. Toyonobori was a wrestler who often teamed with Rikidōzan, and even though his gambling problems had actually soured their relationship behind the scenes, he was seen as the best available successor to Rikidōzan. Toyonobori would become not only the promotion’s ace, but its president. Alongside the troika of Yoshinosato, Kokichi Endo, and Michiaki Yoshimura, Toyonobori was among the council which ran the JWA. Despite major internal reforms after police crackdown which saw the resignations of the major underworld players in company positions, the JWA overcame its difficulties. However, this arrangement couldn’t last. ------------------ Toyonobori’s embezzlement of company funds into gambling activities led to a board meeting on November 24, 1965, where Nippon Productions resolved to dismiss him from the presidential seat. Officially, Toyonobori resigned on January 5, 1966, with a cover story that he had stepped down for medical reasons (ureteral stones). Toyonobori looked to start a new promotion, but he had a problem: he’d already gambled away his whole severance package. So, he approached Hisashi Shinma to help him in this enterprise. Shinma was at this point an employee of major cosmetics manufacturer Max Factor, but he had befriended Toyonobori during his days of bodybuilding training at the JWA dojo. Alongside his father Nobuo, a temple priest, Shinma would help bankroll this new promotion, which Toyonobori announced his intent to form in a Shibuya lodge. Upon this announcement, several young JWA wrestlers left to join what would become Tokyo Pro: Tadaharu Tanaka, Masao Kimura, Masanori Saito, and Mikiyuki Kitazawa. The training camp began in February 1966. However, this left Tokyo Pro with a leaner roster than Toyonobori had expected: the Japanese Wikipedia page states that he had expected the likes of Yoshinosato, Kintaro Oki, Hiro Matsuda, Kantaro Hoshino, and Akihisa Takachiho to also jump ship. So it was that Toyonobori took a trip to Hawaii. Antonio Inoki was on excursion in the United States, looking to return to Japan a seasoned performer for the World League tournament. On March 10, he and his accomplice, referee Oki Shikina, boarded a flight from Los Angeles to Hawaii, where Inoki was to have a joint training session with Giant Baba and Michiaki Yoshimura. However, Inoki was unsure of how much the JWA valued him, particularly compared to Baba. When he arrived in Hawaii, not only were there few press people there to interview him, but his employer hadn’t even bothered to book a hotel room. The JWA had dispatched Baba, Yoshimura, and Kintaro Oki to try to dissuade Inoki from jumping ship. It seemed that they would be successful, as he said that he would fly back to Japan with them on March 19. However, Toyonobori arrived on the same day as Baba, Yoshimura, and Oki, and persuaded Inoki to join him…despite the fact that he’d already gambled away the one million yen which he’d gotten from Nobuo Shinma to entice Inoki. Inoki made an international call on March 21 to tell the JWA he was resigning, and accompanied Toyonobori to return home on April 23. In subsequent years, this incident became known as Taiheiyō jō no Ryakudatsu (“The Pillage on the Pacific Ocean”). On March 21, JWA president Yoshinosato would publicly disclose the real reason for Toyonobori’s resignation. Upon their return to Japan, Inoki was faced with the reality that he’d probably made a terrible mistake. He had no money, Toyonobori had negative money, and there was no TV station to support them anymore. So it was that Inoki began to work with Hisashi Shinma to get this company off the ground. Since the JWA had not yet received official NWA membership, Inoki was able to ask Sam Muchnick for permission to book foreign talent, and he managed to get half a dozen wrestlers out of it, most notably Johnny Powers and Johnny Valentine. [2021.09.15 CORRECTION: As revealed in an Igapro article, this deal was actually facilitated through Bobby Bruns, the man who had brought Rikidozan into the business, with Muchnick's approval.] The JWA got serious about their competition as it was announced that Tokyo Pro would debut at the Kuramae Kokugikan on October 12. It was at this point when they approached Nippon TV about booking the more expensive Nippon Budokan for a show headlined by Fritz von Erich. To be fair, they did have a successful debut on October 12, drawing 11,000 to Kuramae as Inoki defeated Valentine in his first match on Japanese soil since the excursion...but this was quickly made moot when Toyonobori took the profits for what you can already guess. The promotion’s momentum did not sustain itself, as its sister company Orient Promotion was overwhelmed by the JWA. A show at the Osaka Stadium was said to have drawn 8,000 people, but in actuality drew a mere 3,000. (I’m assuming this means it drew 3,000 paid with freebies for the rest, though the wording of the text, at least ran through DeepL, doesn’t use this verbiage.) They would only hold 20 events, as negotiations with Mainichi Broadcasting System broke down over the objections of the station president, Shinzo Takahashi. According to Haruka Eigen, who got his start in the business as a Tokyo Pro recruit, Toyonobori’s use of the promotion as his personal piggy bank went to such an extent that his monthly salary of ¥10,000 was half that of a civil servant, and the company could not afford to purchase rice to feed its trainees. This culminated on November 21. An outdoor show was planned to take place in front of Itabashi Station. It fell through because Toyonobori borrowed money from Orient Promotion, and used Inoki’s money to pay it back. An enraged Inoki pulled out and ordered his fellow wrestlers to do the same. However, the audience would not be informed of the cancellation until an hour after the show had been scheduled to start, and having waited in the cold for nothing, the crowd set the ring ablaze and got the riot police called on them. As this scandal went public, Tokyo Pro’s credibility tanked. They would hold one more small tour from December 14 to 19, culminating in Inoki’s successful defense of the belt he had won from Johnny Valentine against Stan Stasiak, but the box office was dismal. They couldn’t even get 1,000 people to pay to get into the final show at the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium. Fed up with Toyonobori, Inoki and his team secretly moved all their belongings from the Shinjuku office to a new one in Kita-Aoyama. There, they established a new Tokyo Pro Wrestling, with the support of all the wrestlers except Toyonobori and his protege Tanaka, and contacted Isao Yoshihara to establish an alliance with the soon-to-debut International Wrestling Enterprise. Inoki participated in the launch of the International Wrestling Enterprise with his co-workers in Tokyo Pro, working the Pioneer Series in January 1967. On the 8th, he sued Toyonobori and the Shinmas for embezzlement and breach of trust, to the tune of ¥30,000,000, but they countersued, claiming that his living expenses and wife’s purchases had themselves been charged to the company. The business alliance with the IWE was terminated at the end of the month. After being forced to repay several creditors alongside Toyonobori and the Shinmas, Inoki looked to return to the JWA to pay off his debts. He would be accompanied by Kitazawa and Tokyo Pro recruits Haruka Eigen and Katsuhisa Shibata. The source states that Inoki had tried to bring most of Tokyo Pro with him – though not the future Rusher Kimura, since he was close to Toyonobori – but Saito chose to go to the States, and the remaining wrestlers wound up being subsumed into the IWE. Toyonobori and Tanaka hid in the mountains to avoid debt collectors, but eventually gave up and joined the IWE at Isao Yoshihara’s invitation. Meanwhile, Hisashi Shinma would be disowned by his father after this enterprise, and spent four years working as a coal miner before he reentered the business with Inoki. It was through Shinma’s mediation that Toyonobori would briefly join New Japan upon its inception, before quietly leaving the business.

-

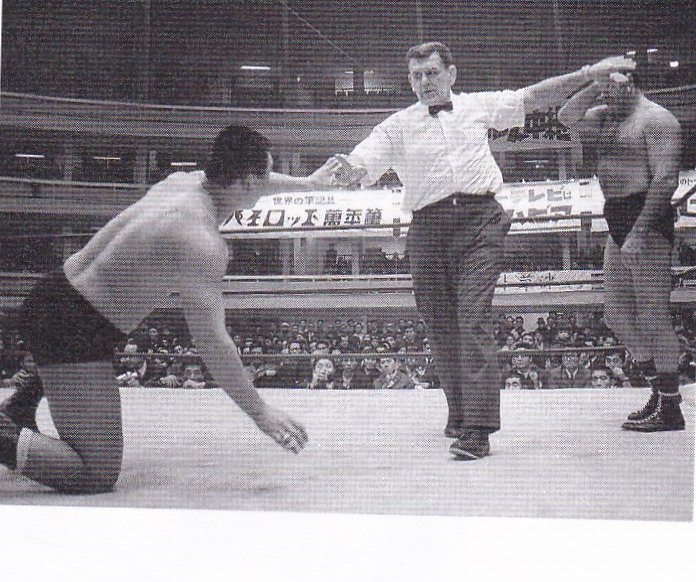

CONTEXT ON THE 1975 OPEN LEAGUE AND INOKI VS ROBINSON I found a pair of Igapro posts (1, 2) on the circumstances around the Inoki/Robinson match, and they provide some info that I wish I had incorporated into the Jumbo bio posts. I may edit some of it in later but I think it’s worth its own post. I may have misrepresented the situation around the 1975 Open League being titled such. It was indeed meant as an implicit challenge to Inoki, but when it was announced on September 29 of that year they did invite NJPW to participate. Inoki had been trying to get the singles match against Baba that he’d wanted since the late JWA days, but he sensed that this was a trap, and refused because New Japan had not received a formal offer, and they had already decided their schedule for the rest of the year. Now, on the surface this was business as usual. Inoki had done this same thing before, challenging Baba without making an actual offer to All Japan and then claiming that Baba had chickened out. What made this case a little different, however, was that the Open League was going to be tied to a memorial show for the twelfth anniversary of Rikidōzan’s death. After his match against Lou Thesz on October 9, Inoki met with Masao Yamamoto, the guardian of Rikidōzan’s estate, to negotiate his participation. However, Inoki refused despite Yamamoto’s insistence, as he had already booked the Kuramae Kokugikan for the Robinson match, and the broadcast schedule was in place. The memorial show was announced in a press conference on October 21, held by Yamamoto and widow Keiko Momota. Yamamoto requested that, as a disciple of Rikidōzan, Inoki would cancel his match against Robinson to work the event. It must be noted that both events were running head-to-head in Tokyo: the Rikidōzan memorial at Budokan, and the NJPW show at Kuramae. Of course, while the Rikidōzan memorial event was to be ostensibly hosted by his surviving family, it was in practicality an All Japan event. And according to this source, Baba was the one who convinced the Rikidōzan family to book it on the same date as the NJPW Kuramae show. As you might imagine, Inoki didn’t budge, so one week later, Yamamoto accused him and NJPW of reneging on their “promise” to participate in the show, essentially calling Inoki a bastard who had forgotten his debt to Rikidōzan. Inoki was hurt by this, but he didn’t budge. In a public statement, Inoki asked for them to consider that what would make Rikidōzan most happy was the flourishing of puroresu, and expressed that his teacher would be proud of the match he was going to have against Robinson. He even went so far as to say that it would be up to the fans to decide whether his match or the Rikidōzan memorial main event was the real Rikidōzan memorial match. (And, I mean, considering that Inoki/Robinson is one of the most famous puro matches of its era, and that the Abdullah the Butcher vs Kintaro Oki antepenultimate match is the only thing from the Rikidōzan memorial show that has been rebroadcast – despite the fact that the Open League might be the most relatively well-preserved puro singles tournament of the 70s – I think Shin Nihon won that battle.) In response, Momota and Yamamoto issued a notice of excommunication in their names, so that Inoki would no longer be able to call himself a disciple of (St.) Rikidōzan (the Great). Before the fateful day, there’s one more incident worth covering. Both events were being supported by Tokyo Sports, who were concerned about Inoki’s refusal to participate in the memorial show and his excommunication. The paper arranged a meeting between Inoki and Momota & Yamamoto on December 6, in which they served as intermediary. Inoki held firm that he would not participate in the memorial show, but nevertheless apologized to the family, which they accepted. That might sound weird, but it makes more sense when you realize that this was, in fact, another trap. When Tokyo Sports published an article on the meeting, New Japan was furious because, in apologizing, Inoki was essentially kowtowing to Baba. As trustworthy a boss as he might have been for gaikokujin, make no mistake: Shohei Baba was a shrewd politician. Besides a match recap that’s basically everything from these posts. However, it drops a few more tidbits: Robinson had been interested in Inoki ever since the two had shared a flight in 1971. Both Lou Thesz and Karl Gotch expressed interest in refereeing the Inoki/Robinson match, but Red Shoes Duggan eventually got the job, as Thesz and Gotch participated as ringside witnesses. This source confirms that the pay cut which led Robinson to jump ship to AJPW was due to New Japan saving money for the Inoki/Ali fight.

-

The grand finale of my SWS narrative is here. Part Three: Black Ship Sinks SWS TAG TEAM TITLES As 1992 began, SWS looked to have finally gotten on track. They kicked the year off with a 1992.01.04 show at the Shizuoka Industrial Hall, where a “mostly non-paying” audience of 4,230 saw the start of a round-robin tournament to crown the first SWS tag team champions. Cagematch does not recognize every tournament match as such, so I’ve had to guess which teams were actually participating: 1. Ryuharagun (Genichiro Tenryu & Ashura Hara) (Revolution) 2. Natural Powers (Haku & Yoshiaki Yatsu) (WWF/Dojo Geki) 3. Shunji & George Takano (Palaistra) 4. Davey Boy Smith & Naoki Sano (WWF/Palaistra) 5. Samson Fuyuki & Takashi Ishikawa (Revolution) 6. Shinichi Nakano & Tatsumi Kitahara (Dojo Geki/Revolution) 7. Kendo Nagasaki & Kenichi Oya (Dojo Geki) In Shizuoka, Ryuharagun defeated the Takanos, the Natural Powers defeated Nagasaki & Oya, and Smith & Sano defeated Fuyuki & Ishikawa. That same night, NJPW held their annual Dome show, and as reported in the January 10 Observer, native interpromotional cooperation finally seemed to be a real possibility for SWS. After Japanese postage company Sagawa Express, which had been backing Inoki’s “political adventures” (I know Sagawa was sold NJPW stock several years before), decided to cut back on such expenses, Inoki had approached Hachiro Tanaka to sponsor him. [1] Meltzer reported that the two had reached a deal which included a secretly booked Dome show in the future, with rumblings of a Choshu/Tenryu headliner. This was supported by Choshu’s backstage promo after the Dome main event, in which he had defeated Tatsumi Fujinami to unify the IWGP Heavyweight and Greatest 18 Club championships. In what Meltzer described as a “Jerry Lawler-type interview”, Choshu challenged wrestlers from other promotions and directly name-dropped Tenryu. However, this would go up in smoke the following month. NJPW president Seiji Sakaguchi met with Tanaka to try to negotiate an out-of-court settlement to New Japan’s lawsuit against SWS regarding Sano and Takano, after which Sakaguchi publicly admitted he had done so, but denied that a co-promotional show would happen, or that Inoki had even spoken to Tanaka. [2] On 1992.01.06, at the Nagoya Conference Center, Ryuharagun defeated Fuyuki & Ishikawa, Smith & Sano defeated Nakano & Kitahara, and the Natural Powers went to a no-contest with the Takanos. 1992.01.08 saw SWS’s first 1992 event in a major market, running the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium. As for the tag tournament, Smith & Sano went over the Takanos, and the Natural Powers avenged their August 1991 loss to Ryuharagun, when Tenryu himself took the pinfall. However, this event would perhaps become most infamous for its opening match. In a tag match alongside Nobukazu Hirai against Apollo Sugawara and Toshiyuki Nakahara, the ex-NJPW junior Akira Katayama botched a tope, fracturing his fourth cervical vertebrae and permanently losing the use of his legs. It may as well have been an omen of things to come. At a Korakuen show four days later, their last of January, Ryuharagun defeated Nakano and Kitahara to further the tournament. SWS began February with a 1992.02.09 show at the Isesaki Civic Gymnasium. As far as (presumed) tournament matches went, Ryuharagun went over Nagasaki & Oya and the Natural Powers beat Fuyuki & Ishikawa, but that wasn’t the only interesting thing to happen on the card. For one, Marty Jannetty showed up for his SWS Junior Heavyweight title shot against Naoki Sano, despite Meltzer having reported that his suspension from Titan Sports had thrown a wrench in these plans. Elsewhere, Ultimo finally had some luchadors to work with, as Kato Kung Lee, Blue Panther, and Emilio Charles Jr. came over from CMLL. [3] The following night, the tag tournament continued in the Aizuwakamatsu Prefectural Gymnasium, as the Takanos defeated Nagasaki & Oya, the Natural Powers suffered what would be their only loss of the tournament against Nakano & Kitahara, and Ryuharagun went over Smith & Sano. On 1992.02.12, at SWS The Battle Hall VII in a sold-out Korakuen, Smith & Sano defeated Nagasaki & Oya by DQ, the Natural Powers beat the Takanos, and Nakano & Kitahara defeated Fuyuki & Ishikawa. The tournament ended on 1992.02.14, at the Kyoto Prefectural Gymnasium. Ryuharagun defeated Nakano & Kitahara, and the Natural Powers defeated Smith & Marty Jannetty. (Sano was nowhere to be found on this card and the contemporaneous Observers don’t say anything about it, so my best guess is that this was tied to the circumstances behind the 1992.02.12 DQ win.) As was to be expected, the tag title tournament went to a Ryuharagun-Natural Powers rematch when both finished the round-robin with 5-1 records, and the Natural Powers won. ROAD TO THE BATTLE OF KINGS The Feburary 10 Observer had reported that Tenryu was pursuing a deal for a singles match against either the Undertaker or Ric Flair, to headline a major event at the Tokyo City Gymnasium on 1992.04.18. Over the following weeks, the plans took shape. Taker would work dates on 1992.03.18 and 03.22, and the March 2 Observer confirmed that Flair would make his SWS debut in April. March began for the company on 1992.03.14 at the Aomori Prefectural Gymnasium. Perhaps the most notable thing about this show was that El Dandy returned to SWS for the first time since January 1991 to make Ultimo do his first job for the company. Elsewhere, Tenryu and Ishikawa were defeated by Nagasaki and the Berzerker, the latter of whom would be pushed during this tour as a Brody clone, and the Natural Powers defeated the Takanos in 23:24. Four days later in Niigata, Taker debuted with a singles win over Ishikawa, and the Natural Powers retained the tag titles against, once again, the Takanos. SWS The Battle Hall VIII took place in Korakuen on 1992.03.22, as a Sunday noon show since All Japan had the hall booked for 6:30, and was topped by two singles matches in which Yoshiaki Yatsu and Taker defeated Ashura Hara and Haku respectively. More trouble arose for the promotion that month when WOWOW declined to renew their one-year television deal. After all, the station was drawing higher ratings with their broadcasts of Fighting Network RINGS. Their last broadcast of SWS material was on March 28. However, the promotion would reach a deal with TV Tokyo for a monthly one-hour slot. (An uncited claim on the Japanese Wikipedia SWS page claims that the Nishimatsu construction company sponsored the program which would be called “Gekito SWS Pro-Wrestling”.) SWS held three events in April, from 04.16 to 04.18. On top of now-former WWF Champion Ric Flair’s participation on all three dates, these shows also saw the Natural Disasters (whom I neglected to mention had unsuccessfully challenged for the Road Warriors’ WWF tag titles at SuperWrestle In Tokyo Dome) look to challenge for the SWS tag titles, and El Satanico represented CMLL to put his NWA World Light Heavyweight title on the line against Ultimo. The first of two SWS BATTLE MESSAGE ’92 shows was on 1992.04.16, drawing an announced 3,919 to the Minamiashigara Research and Development Center. In a six-man tag pitting Ryuharagun and Takashi Ishikawa against Flair and the Natural Disasters, Flair went over Ishikawa with a back suplex. In the main event, the Takanos finally overcame the Natural Powers to win the SWS Tag Team titles when Shunji pinned Yatsu. The second BATTLE MESSAGE was the following night. As reported in the April 27 Observer, the announced sellout of 3,960 in the Yokohama Cultural Gymnasium had a paid crowd less than half that. For the main event, Flair went over Tenryu in a buildup singles match. Elsewhere, the Natural Disasters beat the Takanos for the SWS tag titles, and Naoki Sano retained his SWS junior title against Chavo Guerrero. As expected, SWS THE BATTLE OF KINGS took place on 1992.04.18 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium, with an announced crowd of 9,019. After a double pin, Satanico retained his title against Ultimo with a countout victory. The Natural Disasters traded the SWS tag titles back to the Takanos. Sano retained against Guerrero in a title rematch. And finally, Tenryu defeated Ric Flair in a 2/3-falls match. It would be the last time that SWS could claim to project any semblance of stability. FRACTURE According to Igapro, Kabuki resigned as booker back in March; I initially assumed this was an error since the press conference didn’t occur until May, but Igapro had also said that Kabuki had “disappeared” for a time after quitting, and the April 27 Observer states that he was gone as part of an angle. Anyway, he had continued to emphasize Revolution in his work, and dealing with the other factions, as well as Hachiro Tanaka (to whom they always appealed to intervene), drove him to quit the post. He wouldn’t leave the company entirely, but he also left Revolution to perform for the company as a freelancer, in an attempt to prevent Tenryu from being rallied against by the rest of the company by keeping his distance. [4] The May 18 Observer reported that Takashi Ishikawa took over booking, but an uncited claim on SWS’s Japanese Wikipedia page, which I am taking at face value for the time being, is that the position was taken over by the joint efforts of Ishikawa and Goro Tsurumi. Each represented the pro-Tenryu and anti-Tenryu contingents (this is the phrasing that the Igapro SWS articles eventually just switch to, with “anti-Tenryu faction” meant as shorthand for the amalgamation of Palaistra and Dojo Geki), and would draw up their own cards and then present them to each other to negotiate the final card. On May 14, one week after the press conference where Kabuki announced he had stepped down, Yoshiaki Yatsu, who had taken over as head of Dojo Geki after Ichimasa Wakamatsu departed to grieve his wife’s death, [5] announced that he would resign from his position. [6] He also revealed a deep conflict between the warring factions of the company, but he didn’t tell the full story, and it would be years before we got the entire context. SWS had failed to turn a profit, and beyond the upfront investment Tenryu had spent a lot of money since he became president in order to increase its status. Put this on top of the exorbitant WWF booking fees, and all this debt had led to Hachiro Tanaka’s ouster from Megane Super proper. (There was also speculation among the talent that Tenryu, Kabuki, and Akio Sato were pocketing the margin.) With all this pushback from the parent company, as well as the fact that Tanaka had given up his SWS presidential seat, he plotted to break up SWS. That wording is important. To disband SWS would mean a mass liquidation that was sure to damage its parent company’s corporate image, so Tanaka needed to drive SWS’s factions apart. As has been mentioned before, Dojo Geki was originally meant as a buffer between Revolution and Palaistra, with Wakamatsu and Kazuo Sakurada working as mediators between the respective ex-AJPW and ex-NJPW factions. But what was originally intended as a suture to keep SWS together would become the scalpel that cut it open. Yatsu was the best man to play both sides against each other, as he had worked for both AJPW and NJPW, but had a “cold view” of Tenryu as well as Choshu. (The source mentions the latter even though he was never in SWS, so I think it’s meant to mean that that his feelings about Choshu had bled into his general distrust of NJPW back when most of JPW returned there. Also, note that Yatsu was brought into NJPW as an elite from the start, as he had basically been Hisashi Shinma's unsuccessful attempt to have a Jumbo Tsuruta of their own, so the likes of George Takano had not been fond of him to begin with.) To paraphrase Vince McMahon, if anyone was gonna kill Tanaka’s creation, he was gonna do it! Him…and Yoshiaki Yatsu. At some point the two met in Tanaka’s office. His plan was to put words in Yatsu’s mouth suggesting that the stables become independent promotions. Tanaka would be willing to pay them 200 million yen (roughly 212 million yen now, or 1.94 million dollars) a year, but he didn’t even suggest a condition that they would work any joint shows. Yatsu hesitated, as he was tired of wrestling itself and not just SWS, but accepted on the condition that he would receive 200 million yen of hush money so as not to implicate Tanaka and then leave the business. Yatsu went to work, and made proposals to Tenryu and George Takano. Takano agreed that he and Tenryu had irreconcilable differences, but Tenryu wasn’t convinced. He had worked so hard to build their promotion against the slings and arrows of the locker room and the press, and he considered this proposal tantamount to splitting the company up just as it had found its groove. Tenryu and Yatsu’s first meeting went to a dead end, and they agreed to meet at a later date to discuss the matter calmly while promising not to divulge the contents of the meeting. However, Yatsu then concluded on his own that Tenryu would not be convinced by further discussion, and proceeded to call a spontaneous press conference, where Yatsu resigned and revealed the internal situation. As Yatsu must have seen it, shining a light on the matter would be the easiest way to drive the factions to go independent, and he would thus have done his job. But then, Tanaka threw Yatsu under the bus, stating that he had done this on his own, and tying up that loose end. (I presume he never got that hush money either.) He asked Yatsu to “bow down” to him, even if only formally, but Yatsu refused after this betrayal. Now that the matter was public, Tanaka approached Tenryu about cancelling SWS’s upcoming dates so that they could split the promotion, as he had intended. By this time, though, Tenryu had already announced the events for May and June, and had sold tickets, so he couldn’t back out now. He protested that, if necessary, he would book these events with only Revolution and loaned WWF talent. Tenryu probably knew he couldn’t salvage the promotion by this point, but he probably still insisted on fulfilling these obligations in order to thank the fans which had supported them. The anti-Tenryu faction decided to participate in these last events because Yatsu had been contracted to do so, on the condition that they were not involved in matches with Revolution and WWF wrestlers, which would be granted. The last stretch of SWS dates began on 1992.05.18 in the Katsuyama Municipal Gymnasium, drawing a “full house” of 2,630 according to the June 1 Observer. Not much is notable about it except that the delineation between factions so far as the booking was concerned was quite clear. The following night’s show at the Toyama Gymnasium was apparently more notable. According to a last-minute addition to the May 25 Observer, during this show all of the ex-New Japan talent (Takanos, Sano, Oya and Arakawa) entered the ring together to declare that they could not get along with Tenryu. While Meltzer wasn’t aware of the full extent of Tanaka’s plans (the account given in the June 22 Observer was that Yatsu and Nakano were trying to get Palaistra to quit SWS, but that they instead went to Tanaka to form their own group, leaving Yatsu and Nakano out in the cold), by this point he was openly reporting that Tanaka was sick of all the losses he’d accrued, and that he’d realized that the WWF partnership was a mistake, since a Tenryu/Fujiwara singles match likely would've outdrawn Tenryu vs. Hogan. The 1992.05.20 show at the Ishikawa Industrial Hall in Kanazawa drew a “full house” of 3,050. Most notably, Sano defended his junior title against Rick Martel, and the anti-Tenryu faction’s refusal to work with WWF talent meant that, instead of teaming with Haku (and to be clear, Haku worked these dates), Yatsu had to settle for ol’ Kendo Nagasaki as his partner against the Takanos, to predictable results. The May shows ended at Korakuen on 1992.05.22, with an announced crowd of 2,015. By far the most interesting thing about this show was what was billed as Yatsu’s retirement match, in which he faced the Takanos alongside his old JPW chum Shinichi Nakano (who was also quitting SWS). In a display of the turn of public sentiment against the anti-Tenryu faction which is sure to remind readers of One Night Stand 2006, Yatsu threw shirts into the crowd as a parting gift, only for them to throw them back into the ring while mockingly doing Yatsu’s “orya” chant. (Apparently, Nakano was genuinely hurt by this reception.) The next day, SWS held an emergency board meeting. Here, it was decided that the two factions would split into different promotions starting in July. Two days later, at the ANA Hotel in Tokyo, this was announced. SWS ended with four shows in June. The first was at Korakuen on 1992.06.05, drawing 1,980. Then, on 1992.06.16, they ran the Kumamoto Gymnasium to an announced sellout of 3,070. Following this were two shows on 1992.06.18-19, at the Sasebo City Gymnasium (announced sellout of 3,620) and the Nagasaki International Gymnasium (announced sellout of 3,860). Not much is notable except that Shunji Takano was absent for the last three, having suffered a car accident as reported by the June 29 Observer. Hachiro Tanaka would keep his promise to the groups in that he gave both of them financial support for a limited time. WAR would receive the backing of Megane Super for two years, and NOW for one (apparently cut short due to lack of success). Humorously, he would also pay off Tarzan Yamamoto for one year not to slag him in Weekly Pro Wrestling. However, while an SWS postmortem is beyond the scope of what I set out to write (to be clear, I am interested in at least writing something about WAR eventually, if I find stuff that I think might expand the Western narratives, but that’s too major an undertaking for now), I should note that in September, just one month after NOW held its debut show, the Takanos left to form Pro Wrestling Crusaders while lambasting SWS and Megane Super in an article published by Shukan Bunshun. (NOW would replace them with Ishinriki and Umanosuke Ueda, the latter of whom was thirty years deep into his career by that point.) CONCLUSION I’ve seen the SWS called the kurofune (“black ship”) of puroresu, and I’ve evoked this imagery in the titles of these posts. To explain the historical allusion, the black ships were the Western vessels which ended Japan’s isolation at two points in history: first, the Portuguese carracks with pitch-painted hulls, which linked Goa to Nagasaki in the 16th century; then, the American steam-powered warships, which were commanded by Matthew Perry on his 1852-4 expedition of gunboat diplomacy. It’s an apt metaphor for SWS, actually, because the most consequential things that both kurofune incidents sparked came from within Japan. Whatever one might say about Christian expansionism, the external stimuli of Portuguese missionaries ultimately provoked the Japanese peasantry themselves to dissent in the Shimabara Rebellion. And when the kurofune came again, the Bakumatsu which ended the feudal period of Japan also came from within. Similarly, Tanaka could only buy his way into the wrestling business due to the internal tensions already present during the Baba/Inoki era of puroresu. SWS might not have lasted long, and it might not have reached its potential – the NJPW/WAR feud would end up fulfilling the implied promise of the Revolution vs. Palaistra setup of SWS, to a greater degree than SWS itself ever could have – but it was a necessary chapter in early Heisei puroresu. From what it itself entailed, to what it drove its competitors to adopt in the wake of the exodus that gave it shape (especially All Japan), SWS pulled a major trigger on what made the 1990s such an important era in Japanese wrestling history.

-

[1985-09-03-AJPW] Kuniaki Kobayashi vs Tiger Mask II

KinchStalker replied to cactus's topic in September 1985

I think you got the year and month switched up there. -

KinchStalker's Puroresu History Thread Leftover Posts - Prt 2

KinchStalker replied to DGinnetty's topic in Pro Wrestling

Thanks for the tip, I've edited accordingly. -

Finally, I have completed (part two of) Part Two of my SWS narrative. (Also, check footnotes for a bonus tangent following up on Koji Kitao and his infamous UWFi tenure.) SWS Part Two: Black Ship Docks (2/2) HIGHWAY TO HARA The Igapro article I am drawing from is not specific as to when this took place, but what we do know is that, at some point after SWS’s formation, there was a discussion amongst the journalists who reported on Tenryu about what could be done to revitalize his career, after the bashing of Weekly Pro and the internal politics had sapped his momentum. The idea was pitched to bring back Ryuharagun, and the journalists, chief among them Kagehiro Osano, began to search on their own for Ashura Hara, who had fallen off the grid since his dismissal from All Japan Pro Wrestling in November 1988. Osano received a lead from an All Japan sales representative that Hara was staying at a sushi restaurant in Sapporo, and asked an acquaintance in the area to visit. However, the owner refused and said that Hara was no longer staying there. Osano told Tenryu this, and while he was sad that he would not be seeing his old friend again, Tenryu reasoned that, perhaps, Hara was happy now that he was free from wrestling. Hara had a lot of mileage on his body coming into professional wrestling from rugby, and according to Tenryu’s 2016 autobiography LIVE FOR TODAY as cited by Japanese Wikipedia, he was struggling to walk by the twilight of his AJPW tenure. He had never let it show in the ring, but even before he was dismissed, Hara had told Tenryu that he believed the spring of 1989 “was [his] limit”. Osano then received another lead to a karaoke bar where Hara was said to be a frequent customer, and gave his business card to the owner to pass to him. He waited to hear back until, in the dead of night, he got a call. The man on the other end said, “You’re looking for Ashura Hara? What on earth do you want with him? He’s become a Yakuza.” Osano had a hunch, and replied “You’re Hara! You called me, didn’t you? Thank God!” Indeed, the caller was Susumu Hara, talking about himself in the third person (and, in my imagination, trying to put on a tough-guy voice). Hara admitted it was him, and told Osano that he had been trying to pay his debts for the past two years so that he could return to the ring, but that he still had them hanging over him and thus had had to remain in seclusion. As he saw it, if he returned to wrestling without resolving this matter, he would “only cause trouble for Gen-chan”. Osano informed Tenryu that he had established contact, but despite Tenryu’s wishes, SWS’s internal strife and Tenryu’s place in the company hierarchy would make bringing Hara into the fold difficult. However, as covered in the end of part one of Part Two, the aftermath of the Koji Kitao incident at SWS Wrestle Dream in Kobe had led to restructuring. Hachiro Tanaka had given his presidential seat to Tenryu to try to right the ship (the July 29 Observer reported that Tenryu’s promotion had been announced ten days earlier), and to resolve the internal conflicts between the roster’s “rooms”, Tenryu had shelved that system for the time being. NATURAL POWERS The kayfabe pretext for Ashura Hara’s return took would take shape in the months which followed. Haku, now King Haku after his defeat of Harley Race, became a frequent SWS gaijin in 1991. The 1991.05.22 SWS show saw the debut of one of the defining tag teams of SWS’s run when Haku formed the Natural Powers with Yoshiaki Yatsu. After wins against Tenryu & Ishikawa, and Naoki Sano & Randy Savage, Haku and Yatsu defeated Tenryu and Savage on 1991.06.07 in the Ryogoku Kokugikan. The Natural Powers racked up a dominant record early on as, until August, they only suffered two losses. [1] Tenryu would be exercising executive authority in bringing Hara into the fold, as everyone outside of Revolution objected to it. Nevertheless, he did so, traveling to Kotoni personally to ask Hara to return. Hara is quoted as saying something to this effect: “If I’m not worth it, please don’t bother. But if I can really help, I’ll put my life in Gen-chan’s hands.” Tenryu ordered Koki Kitahara, who had been Hara’s valet in the (AJPW) Revolution days, to keep all of Hara’s gear so that Ashura could return at any time. It was reported in the July 22 Observer that Tenryu was trying to bring Hara back for a tag match against the Powers on 1991.08.09. The next day, it was announced that Hara had signed with SWS. But, before the money match, Hara would debut for the company on 1991.08.04, in a tag match alongside Ishikawa against Tenryu and Fuyuki. The Igapro article that is my primary source on the subject of Hara’s return noted that Hara struggled with his three years of ring rust in this match, but for what it’s worth the August 19 Observer reported that Hara “was said to have looked about as good as he did when he was fired.” After winning a six-man alongside Ishikawa against the Natural Powers with Shinichi Nakano on 1991.08.05, Ryuharagun faced with the Natural Powers in a proper two-on-two within the context of a one-night tag team tournament on 1991.08.09, at New Revolution For SWS in the Yokohama Arena. After both teams won the first round (Ryuharagun against Nakano and Kazuo Sakurada working under the Kendo Nagasaki gimmick, Natural Powers against Fuyuki and Ishikawa), they met in the semi-final. This time, Tenryu finally pushed through to pin Haku with a powerbomb. But alas, then Ryuharagun were fed to the Road Warriors – oh, I’m sorry, “Legion of Doom” – after only a sub-5:00 Sano/Rick Martel match’s worth of rest time, and the results were predictable for anyone familiar with Animal and Hawk’s Japan work. [2] However, Ryuharagun received a round of applause for their efforts. ROAD TO SUPERWRESTLE IN TOKYO DOME The various Igapro articles on SWS essentially skip the last few months of 1991, so I am pulling from various sources to fill in this gap. If you’re looking for insight on, say, the November singles match between Tenryu and Yatsu, I’m sorry, we’re sold out. The September 6 Observer reported that Hachiro Tanaka had stepped in to bankroll yet another wrestling promotion: the bankrupt UWFi. [3] Around this time, it was announced that SWS would hold a tournament over the following months, beginning on 1991.09.16, to crown a WWF Junior Heavyweight champion, which would culminate at SWS SuperWrestle In Tokyo Dome on 1991.12.12. Meltzer speculated in the September 16 Observer that this would be a tournament between SWS and WWF talent. However, SWS had plans to broaden their juniors division, and on September 30, Kabuki traveled to Mexico to begin negotiations with EMLL (soon to change their name). By this point, EMLL planning department head Antonio Peña had scouted Yoshihiro Asai of Universal Pro-Wrestling. Asai was dissatisfied with how the organization which would later be known as FULL had stuck to running small venues, and had attracted many young wrestlers through Asai’s success, and yet had kept his salary low. In response, his employer had pushed Gran Hamada as their ace instead, and as Asai observed the promotion’s decline, alongside that of its Mexican partner the UWA, Asai decided to join EMLL. Asai debuted as Ultimo Dragon in Mexico on 1991.10.18. Initially having wanted to become the third Tiger Mask, this gimmick was created as per the instructions of Peña, who wanted a more Orientalist gimmick. Four days earlier, SWS had announced their partnership with EMLL. Contrary to Japanese journalism which reported that SWS had pulled Asai out – including, you guessed it, Weekly Pro Wrestling (whether this was an innocent factual error or more partisanship on the part of Tarzan Yamamoto is unknown) – this was not the case. Asai would debut for SWS on 1991.10.28. Overall, the prevailing impression in this period was that SWS was finally getting things on track. According to the November 18 Observer, most SWS tickets were still freebies, but the 1991.10.03 Korakuen show had been a legitimate sellout, and the promotion was winning Tokyo crowds over with the improved workrate. According to the December 16 Observer, Akio Sato arranged a meeting early that month, as All Japan’s 1991 RWTL was concluding, with five unnamed gaijin talent to arrange a jump to the WWF (which by proxy would obviously see them work Japan for SWS). The same issue reported heat between SWS and unnamed reporters for claiming that Hulk Hogan, set to wrestle Tenryu in the SuperWrestle In Tokyo Dome main event, had won back the WWF title from the Undertaker on the 3rd at This Tuesday in Texas. Some of the reporters were aware that the belt would be held up that weekend to continue the Hogan/Taker angle, and considered this deceptive advertising. According to the December 23 Observer, SuperWrestle In Tokyo Dome legitimately drew just over 30,000 of their claimed attendance figure of 61,500, with a card which featured the combined talents of SWS, the WWF, PWFG, and EMLL. Most significantly: the SWS Light Heavyweight title tournament concluded when Naoki Sano went over Rick Martel; the Legion successfully defended their WWF World Tag Team titles against the Natural Disasters; and, in the main event, Hogan went over Tenryu. The SWS looked to be back on track, and a weekly television deal was set to begin in April. However, the burst of the Japanese asset price bubble would soon see Hachiro Tanaka sour on his wrestling enterprises. Part Three of this narrative will cover the fall of SWS.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

I found a clip of a Japanese TV comedian doing a Fujinami impression on a karaoke bit. -

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

I've had Fujinami's attempt to sing his own entrance theme ("Magic Dragon", a lyrical rewrite and rearrangement of an Eddy Grant song) stuck in my head for the past three days. I had to know more about this song, which conjured images of Fujinami laying it down in a recording studio whilst Inoki cheered him on in the booth (à la Boogie Nights). So I looked into it, and found out some funny stuff. 1. The vocal version was only used once (oh, to have been in that crowd), after which an instrumental version was hastily substituted. Fujinami refused to release it on CD a few years later, so it languished in obscurity until it was released on a 1999 King Records compilation. 2. Kengo Kimura said "that's not singing, that's noise." Ever hungry to outshine his tag partner in something, he put out a pair of his own singles (here's one of them). However, as Inoki told him, “there is a difference between ability and popularity,” and sure enough, Fujinami’s single outsold his. 3. Kendo Kashin used it as entrance music during a 2004 European excursion and the 2005 G1 Climax, and remarked that “no matter where in the world you play it, it will make the audience laugh.” 4. According to an uncited claim on its Japanese Wikipedia page, it has gained a minor resurgence in recent years through being featured on “Tatsuro Yamashita’s Sunday Songbook”, the radio show of the King of City Pop himself. It wouldn't fit on this forum (maybe DVDVR?), but I think there's some potential for a tongue-in-cheek thread evaluating the musical forays of vintage puroresu. Though of course, joshi made an entire cottage industry out of it and any examination of the subject would be incomplete without them. -

Honestly I wouldn't be surprised if Baba went over those times so that Brody would have to only do a clean job to him in the finals, which is how both tourneys ended. I know the Osano biography said that Tsuruta's reputation wasn't helped all that much by winning the 1980 Carnival, because he'd done so over Dick Slater instead of the guy who Slater (or, as my friend Rose calls him, Filthy Phallus) was obviously functioning as a proxy of, and who was even *in* said Carnival. I'm not saying Jumbo wasn't more in need of the rub at that point than Baba, but I do suspect that the maneuvering was as much to keep certain gaijins happy as it was to not put Jumbo over Baba.

-

They just weren't thinking in that mode back then. Baba and Jumbo had their own belts, so they were on parallel singles trajectories that would only ever intersect in tournament situations, which of course weren't a factor for the last handful of years that Baba was still prominent in singles matches. For what it's worth I also get the impression that Baba's big singles matches went on for a bit longer than NTV initially planned for them to because of how big a draw the Hansen feud was. Before Ishingun, Japanese vs Japanese was just a difficult proposition to get Japanese promoters to gamble on outside of tournament situations except for special circumstances (Kimura vs Ueda, Inoki vs Kobayashi/Matsuda).

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

Oh wow, I see it. And yeah, as a borderline zoomer, I only know the Jerky Boys through my retrograde musical tastes: specifically, Slowdive's second album title referencing one of their bits. -

With a cursory search I was unable to find this anecdote anywhere, because my results were all either about when Tsuruta was hospitalized later on or, get this, a 2011-2015 manga called Town Doctor Jumbo!!, which got a 13-episode live-action TV adaptation in 2013. This shit is too wild not to share. Apparently, a doctor named Masayoshi Tsuruta returns to work at the Baba Clinic after its founder Kohei Baba dies, and alongside another nurse named Chigusa Nagayo (I think this is an homage to a certain variety show appearance Nagayo and Jumbo did together in 1986) he helps Baba's nurse daughter Asuka, a childhood friend of his, undergo some character development. And there are also such characters as Ichiro Tenryu, Tsuruta's classmate turned professor with "mixed feelings" towards him. Looking at the official episode synopses for the TV series, and the last episode is about getting a liver transplant for someone with hepatitis. It turns out his one surviving relative is his half-brother Tenryu, who refuses to donate his own when Tsuruta and Baba ask him to until he changes his mind...but then Tenryu gets stabbed by a vengeful medical journalist!?!? Okay, it looks like Jumbo was so good that he saved both their lives anyway, and the series ends with Jumbo and Chigusa leaving the clinic, with the new director being a side character I didn't mention earlier...named Mitsunari Misawa. In conclusion, someone made a living for almost half a decade writing an AJPW hospital alternate-universe fanfic manga. Not much to do with GWE, but they earned my respect.

-

His chonmage-cutting ceremony took place on the same event as the second tag, the last show of the year. I know he was given a second row seat for Jumbo vs Terry but I don't think the camera caught him.

-

Gotcha. I'll see if I can look into it to at least figure out where the anecdote might have come from.

-

Thank you for articulating the full implications of the Jumbo/Tenryu rivalry. It's something that ran through the relevant section of the Jumbo bio I transcribed, but you did a better job communicating it there than I ever did. I was also unaware of the IV drip story.

.thumb.jpg.0548c426b882cba794af63adef252446.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.9342cd351a37f60b7a458cd9a8b49db8.jpg)

.png.9a91b867afc223b587b2eba5a36a1e5a.png)