-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

Ah yes, I thought about that one too. One does not simply forget two luchadors dressed as Threepio and Artoo entering the AJPW ring to the Alan Parsons Project.

-

The earliest Fuchi rec that comes to mind (though of course everyone should see the Concession Stand Brawl once) is the 1983.08.31 junior title match against Chavo, which I enjoyed more than anything from the '82 Onita/Chavo series. Also seconding the praise for his work in the 2000-1 run. I thought Fuchi/Liger was the best match on the 2001.01.28 Dome show.

-

I definitely agree, but I think it must be noted that there was a transitional period. IMO the switch doesn't flip until that buildup tag in January 1986, where Jumbo ambushes Choshu beforehand. The volatility of the first phase of the AJPW vs JPW feud (that is, 1985) is a deliberate reflection (or at least a consequence, if the implications are too premeditated there) of the stylistic and ideological disconnect between the two factions, and a fulcrum of that narrative was Jumbo's maddening unflappability. There's a recurring thread in the biography I transcribed about how stubborn Jumbo was in this period to break his composure, and when Choshu called Jumbo "kaibutsu" ("monster") after their singles draw, it was a comment on his inhuman stamina. For as frustrating as that match may be, there is not a single doubt in my mind that it was exactly the match it was intended to be, because it is the fullest expression of that theme. Choshu had to play Jumbo's game, and may or may not have been exposed on those terms in the process...but Jumbo's game was not the way of the future. I won't say that the fact that there was this transitional period meant Jumbo was 'lazy' at some point, but what I will say is that I think the whole "he was almost caught napping [in this era]" thing in the Meltzer obituary is something of a misunderstanding of the role Jumbo played during the feeling-out process.

-

When Akiyama got his push in the late 90s the term actually shifted to Gotsuyo, or "Five Strengths", but that never spread.

-

A few years ago I know OJ commented on how the "chase" narrative Western fans applied to Kawada w/r/t Misawa was not shared among the native fanbase. I specifically recall him bringing up Bret and Owen as the closest Western equivalent he could think of for what the story was intended as.

-

I don't wish to derail this thread too much, but OJ has a point. This isn't to say that 90s AJPW booking lacked its distinctive qualities, but Shitenno puroresu and oudou were marketing (or at least journalistic) terms first and foremost, just as "strong style" had been. I know that Tarzan Yamamoto (for those who don't know, the Weekly Pro Wrestling editor-in-chief who offered his services as a creative consultant to Baba) is cited specifically for propagating the former. The story that I've read is that Shitenno (which I'm presuming is just a standard cultural allusion, just as we might use "Big Four" - hell, I've seen Chosedaigun, which we know as Super Generation Army, used in Japanese articles to refer to baseball players, so that probably wasn't special either) was popularized after 1993.05.21, when all four went over the "gaijin Shitenno" in singles matches (Taue def Spivey, Kobashi def Gordy, Kawada def Williams, Misawa def Hansen). And there's a roster photo from 1996 where everyone has "King's Road" patches on their tracksuit jackets. Again, this doesn't mean that their product was not distinct. But I think that people can get carried away with the oudou talking points to imply certain things that weren't necessarily the case. I'm sure that Kawada's choker reputation did indeed end up biting the company in the ass when he finally went over Misawa. But as satisfying as the moments when Kawada triumphed against him might have been, implying that oudou was leading to a point where he was going to be number one for an extended period doesn't ring true to me. Tenryu may very well have gotten the Triple Crown once or twice more had he stayed, but he and Jumbo were booked as a pair, not as one man eventually overtaking the other on some relay race to carry the company along the King's Road. And in that pair, Tenryu was the underneath, just as Kawada would be.

-

Neither are particularly revelatory, but YouTube recently saw uploads of Jack's 1981 Champion Carnival matches against Baba and Jumbo, albeit both with some clipping. I thought both were minor but enjoyable little nostalgia trips. I don't think that Jumbo's UN title defense against him from soon after made tape, though, which is a real shame.

-

Much appreciated. Grand Prix probably was Mad Dog's doing, or at least due to the connection previously established through him (he was the reason Tetsunosuke Daigo did one last tour in Montreal before he was to return from excursion, which ended up being when he lost his leg).

-

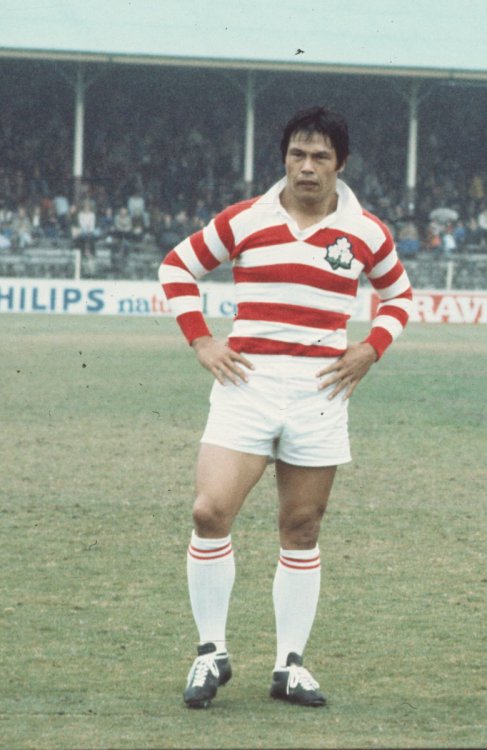

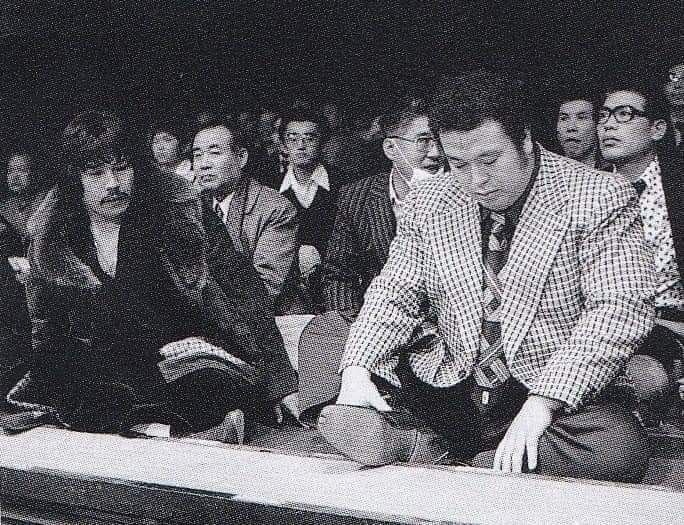

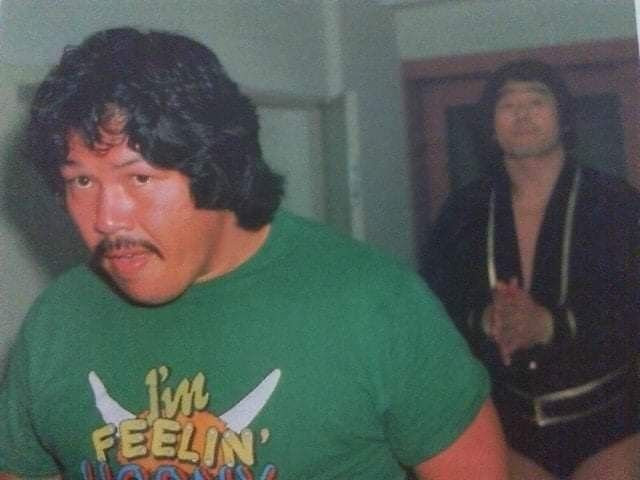

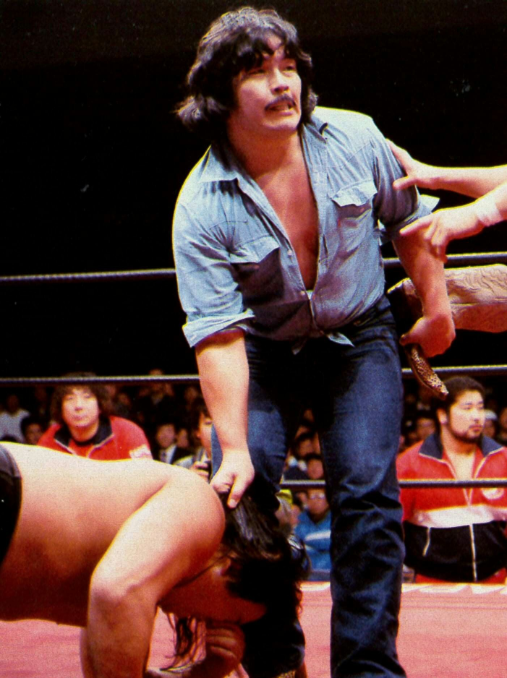

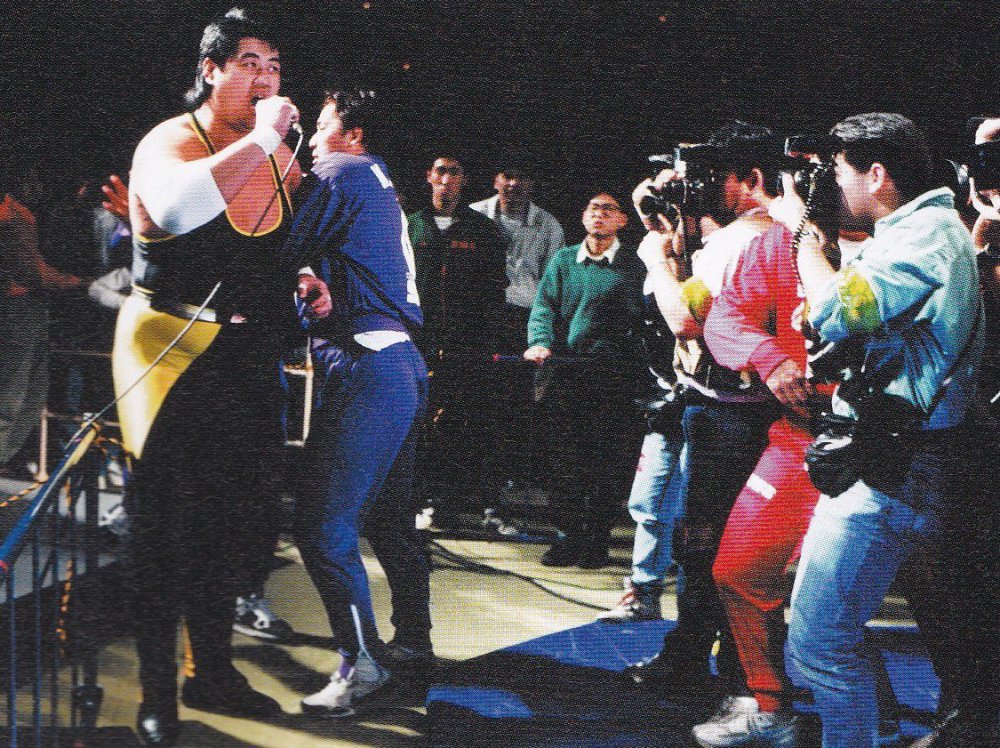

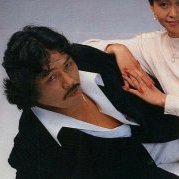

As I stated at the top of the previous post, this extended biography precedes part two of Part Two of the SWS series. To commemorate this, I am changing my avatar for the third time since my account was created, to the image which to this point I had only used as my profile picture on the DVDVR board. I already explained it over there, but I shall do so again in a footnote. [1] On with the story. My next post will recount the circumstances around Hara’s return to professional wrestling and the reformation of Ryuharagun as the second half of Part Two of the SWS history. ASHURA HARA Rugby career Susumu Hara took to rugby in his sophomore year of high school after dabbling in judo and sumo, and after his graduation from Toyo University in 1969, he would be drafted by the Kintetsu Liners, owned by the Kintetsu railroad company (aka Kinki Nippon Railway). Hara spent years working for Kintetsu in his day job as well as his athletic one. He was by all accounts a quite good player, and even became the first Japanese player selected for the World Championships in 1976. However, his day job and training to become a train conductor and driver got in the way of his sports career, and this compounded with Kintetsu’s refusal to give him preferential treatment for working for them in two contexts led him to retire, and then leave the company entirely in 1977. After this, Hara would coach an amateur team owned by author and rugby fan Akiyuki Nosaka (most famous in the West for writing Grave of the Fireflies). However, an interest in professional wrestling was sparked through the scouting of ex-rugby player the Great Kusatsu of the International Wrestling Enterprise. New Japan was also attempting to scout him, but Hara wound up preferring Kusatsu’s offer. On November 29, 1977, Hara announced he would join the IWE, with Nosaka sitting to his right. IWE (1978-1981) Since Hara’s physical conditioning from professional rugby still remained, the IWE put him on the fast-track as far as training went, having Animal Hamaguchi coach him to debut as early as possible. After working the opening match on 1978.06.24 in a Devil Murasaki mask (as revealed in G Spirits #36, the real Murasaki took that day off), Hara’s proper debut would come two days later, in an exhibition match against Isamu Teranishi which was wrestled to a fifteen-minute time-limit draw. In July, Hara was sent on excursion to Calgary for seasoning and further training under Tetsunosuke Daigo and Kazuo Sakurada. As Fighting Hara, he would enjoy a five-day reign that same month with the Stampede Wrestling British Commonwealth Mid-Heavyweight Championship, winning from and then dropping back to Norman Frederick Charles III. In September, Hara moved to West Germany to complete the second phase of his excursion, working for Otto Wanz’s Catch Wrestling Association Edmund Schober in Hannover. Hara returned to Japan on December 7. Much had changed since he had left; I laid this out a few months back in a historical post in the Fujinami/Hara thread on the Matches subforum, but I can give a condensed version here. The IWE had burned their bridge with All Japan during the November Japan League tour when they booked New Japan talent in the undercard of the 1978.11.25 Kuramae Kokugikan show without Baba’s knowledge or consent. While the IWE had formed an alliance with All Japan in 1975, the power disparity of that relationship had ultimately turned the former into, functionally, a satellite organization, and had thus damaged their reputation. Meanwhile, when IWE president Isao Yoshihara unsuccessfully attempted to get the Tokyo District Court to prevent NJPW from booking Ryuma Go, whom they had lured from the IWE, he established contact with NJPW business head Hisashi Shinma, and offered him his presidential seat. By this point New Japan was handily ahead of All Japan in popularity, and Yoshihara thought he could get a relationship with the other side that better favored his company. (Long story short, he was wrong.) So it was that, nine days after his return, Hara accompanied Rusher Kimura to a surprise appearance at NJPW’s 1978.12.16 Kuramae Kokugikan show, where he greeted Tatsumi Fujinami from ringside and announced his intent to challenge him. Fujinami’s reign with the WWF Junior Heavyweight Championship, which had begun in January when he defeated Jose Estrada in Madison Square Garden, had made him a major star in Japan (not to mention that he attracted a periphery demographic – women – to an extent which paralleled and perhaps even surpassed that which his AJPW foil Jumbo Tsuruta had done), and the IWE wanted to market Hara as a junior heavyweight in response. Hara appeared again at Fujinami’s fan gathering at Korakuen Hall on December 26. The next day, at what I am presuming was a press event, he would receive his stage name, Ashura Hara, from none other than Nosaka. Hara began wrestling for the IWE at the start of 1979. Not much is notable about his first few months, but from the footage I’ve seen he did manage to get television time from the start. He would gradually also be incorporated into the cage and chain matches that the IWE built their brand for brutality on. Hara would also, for the only time in IWE history [2], have entrance music commissioned for him. While “Don’t You Know How Much I Love You” by the Love Unlimited Orchestra (but produced, arranged, conducted and orchestrated by Barry White) was used for him at some point, the theme that he would take with him to All Japan was “Ashura”, performed by a group identified as Minotaur which I cannot find any other leads on and which I am convinced was just a one-off session musician gig. On 1979.05.06, Hara defeated Mile Zrno to win the WWU World Junior Heavyweight title, which had been created for him the previous year when Zrno won it in Berlin in December. I don’t know why the title which the IWE already had, the IWA World Mid-Heavyweight title, was not used for Hara, but by this point it had been gathering dust around Isamu Teranishi’s waist for years. A rematch the following night (which exists on tape, but which I have not seen) ended in double countout. Hara’s next pair of defenses would take place two months later, on 1979.07.20 and 1979.07.21, and the latter was a double title match for a belt he’d already held. In his first major Japanese appearance (a draw against Isamu Teranishi on 1979.07.19 was also broadcast in clipped form, though the first Hara match wasn’t), the Dynamite Kid was also defending the Stampede Wrestling British Commonwealth Mid-Heavyweight Championship in their second match, a European-style bout which consisted of eight four-minute rounds. This draw is a frontrunner for the best Hara match of the IWE era, and one of the promotion’s surviving matches which I can most easily and highly recommend. [2021.05.06 correction: A below comment by DGinnetty indicates that the first Dynamite/Hara match was televised as well, but tape has not surfaced.] Dynamite deeply impressed both IWE president Isao Yoshihara and the executives at Tokyo 12 Channel, who exclaimed that he was even better than Billy Robinson. Plans were made for Dynamite to appear again on the next tour, but NJPW’s interest had been piqued enough for them to secure a deal with Stu Hart through Mr. Hito. Stu could not resist the booking fee, nor could he turn down the invitation for his sons Bret and Keith to work for New Japan. As you may know, the 1979.08.17 Stampede show held three NJPW title matches: Seiji Sakaguchi’s defense of the NWF North American Heavyweight title against Tiger Jeet Singh; Fujinami’s defense of the WWF Junior Heavyweight title against Dynamite; and Antonio Inoki’s defense of the NWF Heavyweight title against Stan Hansen. For the IWE Dynamite Series tour, Hara had a pair of defenses on 1979.09.28 and 1979.10.04 against Mark Rocco, making his Japanese debut with this tour; both ended in double countout. According to an Igapro article on Hara’s IWE career which I am using as a primary source (drawn from issues #3 and #11 of the magazine 日本プロレス事件史), the televised Rocco match, alongside the second Zrno one, was considered to have somewhat exposed Hara. The following night, he wrestled NWA World Junior Heavyweight champion Nelson Royal in a double title match to a double knockout. This is most interesting for its aftermath; after All Japan and New Japan, NWA members both, protested that this made Royal’s title invalid, he retired and vacated it. Afterwards, Eddie Graham, Mike LaBelle, and Hisashi Shinma, who were unhappy that Leroy McGuirk held the right to promote the title, banded together to create another version, but this would not be accepted by the whole of the Alliance and would be renamed the NWA International Junior Heavyweight Championship. (The World Junior Heavyweight title was revived in early 1980.) Hara’s last defense of the WWU title in 1979 took place on 1979.11.07, in a cage match against Gypsy Joe, in which he retained after DKO. One week later, he received what would be his only match (albeit non-title) against a current holder of the IWA World Heavyweight title, wrestling Verne Gagne to a loss. (Thirty-six years later, the two would die just one day apart.) The IWE New Pioneer Series would see the Hara/Joe feud continue. Two untelevised WWU title defenses took place on 1980.01.07 and 1980.01.14; the latter would be Hara’s first decisive victory as champion in a 2/3-falls match. Hara defeated Joe once again two days later, in a televised cage match. Hara would finally get his match against Tatsumi Fujinami on 1980.04.03, after a successful WWU title defense against IWE defect Ryuma Go on 1980.03.31. (I know the latter match exists in circulation but it is not publicly uploaded as of writing.) In his shot at Fujinami’s WWF Junior Heavyweight title, Hara lost by submission. Hara was humiliated in what was, besides a two-week IWA World Tag Team title reign for Strong Kobayashi and Haruka Eigen, the last NJPW/IWE interpromotional angle. Hara vacated the WWU title to graduate to the heavyweight division. Although he continued to work for the company on its following tours, he would not appear on television for the rest of 1980. In January 1981, Hara went on an excursion to Mid-South to train as a heavyweight; he was originally going to leave in October, but it took two months to obtain a work visa. During this excursion he wrestled the Super Destroyer Scott Irwin, whose signature maneuver, the superplex, would be taken by Hara. He debuted the new finisher to win his return match against Steve Olsonoski on 1981.04.18. One month later, on 1981.05.16, he and Mighty Inoue defeated Paul Ellering and Terry Nathan to win the IWA World Tag Team titles; Animal Hamaguchi, Inoue’s usual partner, was out of commission to treat his liver. Hara and Inoue would hold the belts until the promotion’s closure, and in fact the first of their two successful defenses, against Gypsy Joe and Carl Fergie on 1981.06.25, was the last IWE match ever broadcast. (Puroresu.com and Cagematch both claim that a Hara/Joe cage match immediately followed this, but I’m skeptical.) Hara and Inoue’s last defense was on 1981.08.08, the IWE’s penultimate show, against Terry Gibbs and Jerry Oates. I’m going to end this section by quoting the final paragraph of my historical post on the Fujinami/Hara match thread: Sixteen months after wrestling Fujinami, Hara found himself on the grounds of an elementary school in Rausu, for a hastily arranged show which would be the ignoble end of the IWE. For their final tour, they hadn't even managed to book Korakuen; the best they could do so far as Tokyo was concerned was a parking lot in Machida. The company's funds were so depleted that the entourage couldn't even pay their own way all the way back to Tokyo, relying on the generosity of a bus driver on the Tōhoku Expressway. Hara had no interest in joining Kimura, Hamaguchi, and Teranishi in NJPW, despite Yoshihara's recommendation. He was still genuinely bitter about this match, and had intended to retire and take over his family farm. But then, Giant Baba would contact IWE commentator Tadao Monma to express interest in him, and the rest is history. AJPW (1981-1988) Yasei no Danpugai (“Wild Dump Guy”) [Yes, this was his actual nickname. There must be some context I’m missing, because I’m getting real “Loose Explosion” vibes.] Signed to a freelance contract, Hara was one of the ex-IWE performers who, in defiance of Isao Yoshihara’s wishes, went to All Japan instead of New Japan: the others were Mighty Inoue and rookies Hiromichi Fuyuki and Apollo Sugawara. [3] Hara was asked if he would be interested in a #4 spot in the company, behind Baba, Jumbo Tsuruta, and Genichiro Tenryu. He made his AJPW debut on 1981.10.02, with a singles match against Tenryu. It’s not a masterpiece or anything, but it’s worth seeing because, outside of an early glimmer or two that comes to mind [4], I think that it’s the earliest Tenryu performance on tape to show recognizable if inchoate shades of his later personality. The two would reach a mutual understanding through this match, and formed a tag team which would compete in the next two iterations of the RWTL. Another theme of the first phase of Hara’s AJPW career was his utilization as a jobber to the foreign stars. Most famously, he was the first opponent of post-NJPW run Stan Hansen in All Japan, falling to the Western Lariat in 2:25. However, there are other matches I would put in this category during this era, against the likes of Terry Funk and Rick Martel. While Hara’s team with Tenryu would continue on-and-off in this first incarnation through 1984, he found his greatest kayfabe success with others. On 1983.02.23, he teamed up with fellow ex-IWE star Mighty Inoue to challenge for the All Asia Tag Team titles, which had been vacated by Akio Sato and Takashi Ishikawa the previous month following Sato’s injury, and defeated the Great Kojika and Motoshi Okuma by disqualification. A rematch on 1983.03.02 saw them go clean over the men who had been synonymous with the belt in the latter half of the previous decade. They would hold the belts for nearly a year, as well as enter the 1983 RWTL together, until they vacated them so that Inoue could focus on chasing the NWA International Junior Heavyweight title, after which Hara would team with Ashura Hara to defeat ex-IWE gaikokujin Gerry Morrow (who had interestingly been booked like a native by the company, as Jiro Inazuma) and Thomas Ivy to win them again on 1984.02.16. Outside of this reign, the last notable matches of Hara’s first run with All Japan were a pair of shots at Tenryu’s NWA United National title, on 1984.04.11 and 1984.04.16. It’s time to get into the story behind Hara’s first departure from All Japan. He had been assigned the task of promoting a show on 1984.10.22 in his hometown of Nagasaki, but had entrusted a friend with the task. When said friend vanished, Hara suddenly went off the grid in shame. It’s said that no posters had even been put up in the city, and Cagematch records the eventual show’s attendance as a paltry 1,800. Because this was a television taping the show could not be canceled. Hitman No word would be given publicly of Hara until 1985.04.03, when he interrupted a singles match between Riki Choshu and Takashi Ishikawa to attack and challenge the former. Igapro states that Hara was brought back into the fold by his (unnamed) sponsor, who was also one of AJPW’s promoters, and who served as his guarantor to bring him back in what I presume due to later information was a pay-per-appearance capacity. Hara began training at Mount Inasu that month, which was reported on by Tokyo Sports. After interfering in another Choshu match on 1985.04.19, Hara was to team up with his old pal Tenryu on 1985.04.24 against Choshu and Animal Hamaguchi, but this would end up being the stage for a breakup angle. Tenryu was frustrated that Hara had refused to talk to him before the match, and Hara eventually blew up, hit Tenryu with a chair, and walked out. Motoshi Okuma stepped in as a replacement, and predictably got eaten alive in 1:27. At the first show of the next tour, on 1985.05.17 (one night after the second JPW tour had ended), Hara interfered again, this time in Tenryu’s match. Hara acquired the nickname “Hitman” due to these actions, and Baba set up a singles match for him against Motoshi Okuma in Hokkaido on 1985.05.19. [5] In his first match in seven months, Hara rolled out his new finisher, the Hitman Lariat, to win in 0:48. His next three matches would likewise be sub-minute squashes against, respectively, Haruka Eigen, Masanobu Kurisu, and Haru Sonoda. On 1985.05.29, he appeared on late-night NTV program 11PM to send a message to Tenryu. At Special Wars in Budokan on 1985.06.21, Hara interfered in the postmatch of the second Tenryu/Choshu singles match. (His involvement was a matter of confusion for several brothers on that match’s thread on this forum, where I explained the matter late last year.) One week later, on the first date of the 85 Heat Wave! Summer Action Wars tour, Hara wrestled his first match of any relative substance since his return, a singles match against Tenryu which predictably spiraled out of control into a no-contest. Soon afterward, Hara would officially sign with the company as a freelancer. While Hara would wrestle alongside his former IWE coworkers, now configured as Kokusai Ketsumeigun (“International Blood Army”), he never actually joined their faction. [Edit: this is worded misleadingly, as not every ex-IWE guy in All Japan was a member. Mighty Inoue wasn't aligned, nor was Fuyuki when he returned. Hamaguchi and Teranishi were Ishingun guys.] It was under these circumstances, though, that he would serve as Rusher Kimura’s partner in the 1985 RWTL. Kokusai Ketsumeigun basically died in March 1986 when, after the Calgary Hurricanes officially joined AJPW, faction members Ryuma Go, Apollo Sugawara, and Masuhiko Takasugi were dismissed from the company (although Go would later work the 1987 Summer Action Series tour as Kimura’s jobber tag partner). Hara would continue to wrestle alongside Kimura and Tsurumi, which also occasionally aligned him with Tiger Jeet Singh and the Great Kabuki. In the last couple months of the year, Hara would also wrestle alongside members of the Calgary Hurricanes, most notably faction leader Super Strong Machine. The two would win the All Asia Tag Team titles on 1986.10.30, and would enter the 1986 RWTL together, although an SSM injury partway through would take them out of the picture by forfeit. Revolution The first five months of 1987 were generally unremarkable for Hara, as SSM’s return to New Japan led to his final All Asia tag reign ending by vacation. However, things picked up when he reunited with Genichiro Tenryu, when their tag team would finally become known as Ryuharagun. As I covered earlier in this thread, Tenryu asked Baba to let him split up from Tsuruta, because he wanted to challenge the complacency that he had seen his partner fall back into in the wake of Choshu and company’s departure back to New Japan. Tenryu and Hara wrestled their first match alongside each other in three years on 1987.06.05, defeating Hiroshi Wajima and Motoshi Okuma. The night before, the photo at the head of this section was taken, as Tenryu’s Gong reporter (and later, Jumbo biography author) Kagehiro Osano was taken out to dinner by the two. [6] Interestingly, these two still considered themselves rivals in kayfabe, at least at first, so they traveled separately. Tenryu rode with the ring setup crew, while Hara used his old knowledge of the railroad to get around. Revolution as we know it began to take shape in the late summer. As I have previously written, Samson Fuyuki took his time joining the faction, after a swerve in August which saw him split up from his excursion buddy Toshiaki Kawada. However, through the mediation of his old IWE mentor and co-trainer Hara, Fuyuki would join back up with Kawada by the end of the next tour. This would pay off in the following years when the two, wrestling as Footloose, built the foundation for the early-90s golden age of the All Asia tag titles. [7] (Tenryu’s valet Yoshinari Ogawa would also join the faction.) Revolution would become known for bucking the trend of phoned-in B-shows, continuing to deliver quality performances on the provincial circuit: “The TV show is the trailer. If you want to see the real show, come to the region. We'll show you plenty!” [8] As for the core of the group, Tenryu and Hara would win the PWF Tag Team titles on an untelevised 1987.09.03 show against Stan Hansen and Austin Idol. (According to this page which purports to have the results for the tour, Idol was counted out at 12:18.) Nine days later, they successfully defended against Hansen and Joel Deaton, and on 1987.10.16, they retained once again against Jumbo Tsuruta and Hiroshi Wajima. In between those matches, Hara also had the last significant singles match of his AJPW tenure, wrestling Jumbo Tsuruta to a loss in a buildup to the second match in the 1987-1990 Jumbo/Tenryu series. Entering the 1987 RWTL together, Tenryu and Hara went to a three-way tie for second place, after their final match against Hansen and Terry Gordy went to a double countout, and the Olympians defeated Bruiser Brody and Jimmy Snuka in the main event. Ryuharagun’s first match of the new year was (not counting their first encounter in the RWTL) the first of six matches against the Olympians, which they lost when Hara was counted out. This series would be an important factor in the unification of the PWF and NWA International Tag Team championships, and it is to put it mildly a career highlight for Hara. Between the first and second of these matches, though, Ryuharagun would make two successful defenses of the PWF belts. The first was against Abdullah the Butcher and TNT (Savio Vega) on 1988.01.09, and their second was against Bruiser Brody and Tommy Rich on 1988.04.22, in what would be Brody’s last match for All Japan. And while this objectively isn’t that important, I would be remiss not to mention Ryuharagun’s 1988.03.05 buildup tag to the Tenryu/Hansen PWF Heavyweight/NWA United National double title match, which Hansen would derail in an amazing worked shoot outburst, immortalized in Botchamania, after a knockout from Tenryu and Hara’s sandwich lariat. (“NOBODY POTATOES ME!!!”) On 1988.06.04, Ryuharagun dropped the PWF Tag Team titles to the Olympians, who unified them with the NWA International Tag Team titles six days later upon defeating the Road Warriors by DQ. Two months later, Ryuharagun would have their day. The 1988.08.29 Budokan show had been planned to feature the fan-voted main event of Jumbo Tsuruta and Bruiser Brody vs. Genichiro Tenryu and Stan Hansen. However, Brody’s murder in Puerto Rico would obviously end these plans, and the card was retooled into what would become known as the Bruiser Brody Memorial Night. In the main event, Ryuharagun defeated the Olympians for the AJPW World Tag Team titles, in the best iteration of their matchup to date, the best AJPW tag match since the end of the KakuRyu/Ishingun feud, and to this point the best match of Ashura Hara’s career. When I said Ryuharagun would have their day, I meant that literally. For the following night, they dropped the belts back. But their kayfabe loss was our gain, because this match was even better. While I am largely unfamiliar with Hara’s SWS/WAR work – the only thing I have seen is the 1993.02.16 NJPW/WAR ten-man, which I thought was great when I saw it and plan to rewatch in sequence with the full feud but which I don’t remember being this great – I am comfortable calling this the peak. Much of that is down to having the best Jumbo vs Tenryu stuff up to that point, sure, but Hara’s supporting performance is close to perfection. If you come away from this post deciding to watch just one match, well, it would be really cool if you watched the BBMN tag first, but if you must, make it this one. Another pair of Olympians matches followed, on 1988.09.15 (I think Roy Lucier's upload of the AJPW TV episode is geoblocked in the US so I can't find it to link) and 1988.10.26, but they would be the last significant matches of this phase of Hara’s career. The common story behind Ashura Hara’s dismissal from All Japan depicts him as a man deep over his head in debts incurred from gambling. This has been the story told in Western narratives for many years, but it’s not quite the full story. Hara was generous to a fault, and it appears that hanging out with the famously giving Tenryu was a bad decision for his financial health. As I wrote on DVDVR, “Tenryu was in a position where he could afford to, for instance, stuff an envelope filled with ¥10,000 bills into Shiro Koshinaka's pocket as a parting gift after personally convincing Baba to let him start a new life in New Japan. Hara's pockets, however, weren't that deep, and all the drinks he bought for the younger guys hit his wallet hard.” Whatever the reasons, it became too much to handle. Shady debt-collector types started hanging around All Japan events, eventually getting bold enough to show up at major shows where network executives were present. Baba had already been writing Hara’s paychecks out to his wife in order to try not to be as much of an enabler, but as you all know, he eventually had to cut him loose. The night before the 1988 RWTL, Baba announced Hara’s dismissal during a press conference at the Hotel Pacific Tokyo…to which Hara was in debt.

-

Showing Older Wrestling to Newer Fans (or Vice Versa?)

KinchStalker replied to funkdoc's topic in Pro Wrestling

Seconding this. I've frequently observed it myself amongst my online circle. -

Here's the first part of Part Two of the SWS series, which goes up to the 1991.04.02 Wrestle Dream in Kobe show. The source I've been consulting only tells much of the rest of the story in 1991 through the lens of the reformation of Ryuhara-gun, Tenryu's tag team with Ashura Hara, so that will be its own post, preceded by an extended Hara biography up to that point. SWS Part Two: Black Ship Docks (1/2) ROAD TO WRESTLEFEST 1991 The first SWS show with loaned WWF talent was (according to Cagematch) their eighth event, which took place on December 6, 1990, at the Welfare Hall in Himeji. The WWF representatives were the tag teams of Ted DiBiase and Greg Valentine, the Bushwhackers, and the Rougeaus, as well as half of the constituents of the opening six-man tag (the Brooklyn Brawler, Beef Wellington, and Rochester Roadblock). All these men also worked the following night’s show at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium, which drew 6,390, though the January 8 Observer reported under 3,000 paid. According to the December 7 Observer, the WWF had control of the booking of all their wrestlers, and while Meltzer doesn’t state this I presume Akio Sato was heavily involved in the process; he and Titan Sports business VP Dick Glover had both visited Japan in November to announce the partnership. SWS began the new year with their 1991.01.04 show at the Tokyo Bay NK Hall in Urayasu. While announced as a sellout of 5,909, the 1991.01.21 Observer reported that, at 3,500 with less than half paid, the actual crowd was the smallest that a wrestling event at the venue had ever drawn. The show itself was said to have been Japan’s worst in years, with a Rockers vs Fuyuki/Kitahara tag being the sole three-star match on the card as it was reported to Meltzer. The main event, which saw Tenryu and Kitao go over Tito Santana and Haku, reportedly saw the crowd laughing at Kitao. At this point in the company, Kitao had a second-place tournament performance (1990.12.07, losing to Tenryu), a main event tag victory (1990.11.22, w/Tenryu over Sano/Shunji Takano), and three squash matches to his name, but it wasn’t shaking off his poor reputation. And as reported in a later Observer, this show gave Tarzan Yamamoto and Weekly Pro Wrestling plenty of ammunition. On January 22, Isao Takagi (Dojo Geki) was dismissed. According to the February 18 Observer, this was because he was skipping too many training sessions due to his claimed injuries and gambling habits. February would see SWS block Weekly Pro from ringside and interview access completely, though ironically this appears to have arisen from an honest error, rather than Yamamoto’s antics. SWS purchased a full-page ad in the magazine for the 1991.03.30 Tokyo Dome show, and upon seeing it complained and requested corrections. However, the revised version of the ad did not make it to the presses. Yamamoto revealed in subsequent years that this was a printer’s mistake, and that he tried to tell Hachiro Tanaka what had happened, but considering all he had printed about SWS up to that point he was perhaps understandably not believed. The Weekly Pro ban was reported in the March 11 Observer, though Dave was unaware of the straw that had broken the camel’s back. This same issue reported that other outlets heaped praise upon the 1991.02.24 SWS Korakuen Hall show (which featured no WWF talent) in response, wishing to curry favor with the promotion which had just bared its fangs to their biggest competitor, though Meltzer’s “unaffiliated sources” reported that the card wasn’t that good. A second round of auditions was held on 1991.02.24, with two passing: future WAR junior champ Yuji Yasuraoka and Toshiyuki Nakahara (both Revolution). That same day, two other signings were announced, one of whom was Hikaru Kawabata (Dojo Geki). As far as new talent went, however, the most important thing going was obviously SWS’s partnership with Shin UWF Fujiwara Gumi, later to be renamed Professional Wrestling Fujiwara Gumi. (See the post above for the rundown on the fracture of Newborn UWF, which led to FG’s formation.) The timeline in the SWS’s Japanese Wikipedia page places the announcement at March 13, 1991, but it was a foregone conclusion long before even if one wasn’t following the money. According to the February 11 Observer, Nikkan Sports reported that Fujiwara, Funaki, and Suzuki were SWS-bound, and the March 11 issue stated that Funaki/Sano had been announced for the Dome show. My guess is that the March 13 announcement was that Fujiwara-gumi were partnering with SWS as their own room. We should probably address that now. As stated in part one, the heya system was Tenryu’s idea, a transplant from sumo, and its “rooms” were not just kayfabe factional entities, but distinct units within the company structure. To Tenryu’s credit, it was a pretty good idea; the differences between AJPW and NJPW company culture probably would have been irreconcilable had he tried to push those same-sided magnets together into a single locker room. And the third faction, Wakamatsu and Sakurada’s Dojo Geki, was intended to serve as a mediating party between Revolution and Palaistra. However, to skip ahead just a bit, Sakurada and Wakamatsu would soon depart: Sakurada back to America, and Wakamatsu to his seriously ill wife. The appointment of Kabuki as booker was an asymmetrical arrangement, as his booking favored those who had left All Japan alongside him, and was even done with Tenryu’s consultation. This was not an arrangement that George Takano, or indeed many others, were happy with. They also saw that the WWF partnership was hinged on ex-All Japan buddies Tenryu, Kabuki, and Akio Sato, and that Revolution were favored in the booking of WWF-loaned talent. (In fact, as had been reported in the November 19 Observer it had only been Tenryu and Kabuki accompanying Hachiro Tanaka to negotiate to secure the WWF partnership in the first place.) The wrestlers would appeal directly to Tanaka, who then stepped in and interfered with Kabuki and Tenryu’s decisions. SWS/WWF Wrestlefest in Tokyo Dome took place on 1991.03.30. The claimed attendance was a sporting event record for the venue, at 64,618. The April 8 Observer reported that the real attendance was somewhere from 42-45,000, with an estimation of around half of that paid. The following week, Dave would get the real juicy details. 30,000 of that attendance was what the Dome’s box office had reported “out” – as in, the individual tickets bought directly from them as well as bulk tickets ordered by ticket sellers (the paid attendance was reported as “probably near” that amount) – but the show had been papered by a massive freebie campaign from Megane Super, in which they distributed 50,000 coupons in the Tokyo area which could be redeemed for two tickets. The WWF had also done a trade-off campaign with Armed Forces Radio, in order to get stationed US personnel and their families to get crowd reactions for the “American spots”, but this campaign wasn’t as successful as their previous one for the 1990.04.13 Dome show. SWS Wrestle Dream in Kobe, held two days later, would be the stage for one of the most infamous shoot incidents in modern wrestling history…Apollo Sugawara walking out of his match against Minoru Suzuki. Nah, I’m just screwing with you. Let’s get to what you came here for. THUNDER STORM BREAKS DOWN Above: Koji Kitao makes an infamous comment on the microphone after his disastrous rematch against Earthquake. At the Dome show, Koji Kitao had put over Earthquake: that is, the Canadian former rikishi John Tenta, who had retired from sumo in 1986 [1] to join All Japan Pro Wrestling, before signing with the WWF in 1989 to perform somewhere closer to home. A 2021 web article for Sports Graphic Number by writer Genki Horie, published on the thirtieth anniversary of the Kobe show, advances a couple theories about the incident at the Kobe show. The first is that Kitao’s head got gassed up by Don Arakawa and others backstage; Apollo Sugawara claims that Kitao had called him afterwards and threatened to no-show Kobe. The second theory is given much more real estate in the article since it is sourced from an interview the author himself conducted with Tenta. According to Tenta, the intent was not to trade wins between the ex-yokozuna and ex-makushita, but for Earthquake to beat Kitao both times. However, Kitao complained that Tenta had injured his breastbone with his Earthquake Splash, although Tenta found that ridiculous (nobody he’d worked with in the WWF had complained about the move). Then, as Tenta told it, Kabuki flew into the dressing room to tell him his intentions. What he said to Tenta translated as “let’s give Kitao some flowers today.” (As a supplement to DeepL, I checked RomajiDesu’s translation feature, which breaks down smaller passages into romaji and translates the individual units, in order to see whether this was wrong. But no, this is what was written; I don’t know a specific colloquial meaning, but my tentative guess is that Kabuki decided at the last minute to put Kitao over to keep things running smoothly. However, apparently in an episode of Between the Sheets Bixenspan and Zellner interpreted/reported this as Kabuki telling him to actively provoke Kitao.) Tenta stated that he wanted to have a good match at the start, so he began working in good faith. However, Kitao unsuccessfully tried to blindside him with a Fujiwara armbar attempt out of the collar-and-elbow. What ensued famously manifested as a minute or so of uncooperative shoot-ish working between the two until, as captured in this photo, Kitao refused to lock up, instead giving a certain gesture to Tenta. (I have seen this commonly called an “eyepoke” gesture, but Japanese Wikipedia interprets it as a handgun gesture. This had been seen in Japan around this time to indicate a gachinko/”cement match”.) According to Tenta’s testimony, this was the point when he no longer took the match seriously, and sure enough, the rest of the match saw the two staring each other down and talking shit until Kitao got disqualified by kicking the referee. As you likely know, Kitao grabbed the microphone afterwards (fancam footage) and exposed ‘da business. Tenta was not proud of the match, but he did note that when he returned to America, the rumor had grown to the proportion that he had actually beaten Kitao in a shoot, which boosted his reputation backstage. (That’s not to imply that Tenta wasn’t tough; I recently learned that we might have him to thank for sparing our timeline from a full-on Raja Lion run in AJPW, after they sparred in the dojo and Tenta trounced him.) Honestly, what I find more interesting for the purposes of our narrative is not the circumstances which led to the incident, but what happened immediately afterward. After Kitao’s death in 2019, Masakatsu Funaki uploaded a vlog to his YouTube channel, where he aired out some laundry that I have to mention. Hachiro Tanaka’s wife was working as an on-site supervisor, and when she warned him about his behavior, Kitao threw a chair at her during his backstage tantrum. It didn’t hit her, but from Funaki’s testimony she would have been injured if it had. This went unreported, but Funaki claims that it was a turning point in Hachiro Tanaka’s attitude towards his wrestlers, and understandably so. Tenryu and Kabuki took responsibility for the incident, and so Tenryu asked Tanaka to demote both of them from their respective roles as director and booker. Initially Kitao was punished with a fine and suspension, but Palaistra and Dojo Geki objected to such leniency. In an emergency meeting, Tenryu and Kabuki asked for Kitao’s resignation, and Tanaka was forced to fire him. Then, Tanaka would step down from his presidential role, deciding to give the seat to Tenryu to “take care of everything”. Under the Tenryu regime, Kabuki would not step down as booker after all, but changes were implemented that temporarily suspended the heya system, and it appears that all the respective heads were, for a time, allowed to be involved in the booking. (Note: Tanaka would try to bring Kitao back at some point as a member of Fujiwara Gumi, but the meeting went nowhere after Kitao took out his laptop, where he had written his pitch for how he wanted his matches to go, and well, let's just say it wasn't PWFG-compatible.) Above: President Tenryu.

-

The saturation of the matchguide since they opened up submissions last July (I'm definitely guilty of that, having taken a completist approach to catalog AJPW tape) might affect that. If so, I apologize for my part in it.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

AJPW has established a junior wrestling club. 全日本プロレスジュニアレスリングクラブ (@ajpw.jr) • Instagram photos and videos -

I might experiment with YouTube's autocaption feature, downloading them as .srt's and feeding them into DeepL.

-

I'm going through the IWE footage right now myself. I'm only just about done with July 1979 so I'm only a couple defenses into Hara's junior title reign, but both of his defenses I've seen thus far were good: the 1979.05.06 Mile Zrno match, and *especially* the 1979.07.21 Dynamite Kid title vs title match. The latter is unique in that it's an eight-round bout. I'm not going to participate in GWE myself but as I watch this stuff I'll be happy to point out more Hara matches. Also the 1980 Fujinami match, while being the end of Hara's junior run, is of a piece with that era of his work.

-

His Japanese Wikipedia entry has an entire section dedicated to it with extensive quotes, which I've ran through DeepL before. A lot of it is very culturally specific, but an easily accessible subject was his frequent attempts to "help" eternal bachelor Fuchi get laid. "Fuchi, did you see Taue's vigorous fighting? Hey, Fuchi, do you know why he's doing that? Because he got married, motherfucker! It's time for you to get married too, you son of a bitch! You know what? If you don't have a matchmaker, I'll be one for you." Kimura "considered" introducing one of his relatives to Fuchi, but decided against it because he didn't want to be related to him. Putting over the local women: ""Fuchi, how about an Akita beauty? Akita beauties are good, Fuchi! Get an Akita beauty as a wife, you bastard!" "I'm going to find your wife in this hall." Then he proceeds to ask an elderly woman in the crowd to marry Fuchi. Advising Fuchi to sing "Bésame Mucho" at karaoke to seduce someone. Also, on the day that he was supposed to face Tenryu in a singles match, but Tenryu had already left the company, Kimura told the audience never to buy from Megane Super even if they developed presbyopia, and the audience erupted.

-

The Mad Dog Vachon match from 1977 is also a fun brawl. I gave it a **3/4(5/10) but that was more due to it being clipped. (I tend not to deal in hypotheses about how good matches were in the building from edited versions when I rate them, at least not in terms of my submissions on that site.)

-

[1979-02-19-WWWF-MSG, NY] Bob Backlund vs Greg Valentine

KinchStalker replied to Superstar Sleeze's topic in February 1979

I don't have much to add, but I just want to say that this absolutely floored me when I sat down to watch it three weeks ago. Having only seen three Backlund matches to that point (the 1974 AJPW tag, the October 78 Ernie Ladd defense, and the WWF Superstars match against Bret), I had liked what I'd seen thus far but I was completely unprepared for this. I currently have it at a ****3/4, part of a four-way tie for my top-rated MOTD. I surely thought Jumbo/Bockwinkel would be my MOTY, and I still love that match dearly (and can at least rationalize that as my self-imposed rule not to go above ****1/2 for matches we have less than 90% of), but upon seeing this it couldn't even settle for being MOTM. Damn. -

Yeah, those tags are great. I actually think it was you proselytizing about them on a different message board a while back that made me check them out. There's also a 1977 Jumbo singles match from his Trial Series that popped up on YouTube at literally the very end of 2020 (in my timezone, at least). It's not major but it's worth seeing.

-

[1969-12-3 JWA] Dory Funk Jr. vs Giant Baba

KinchStalker replied to Superstar Sleeze's topic in 1969

It was among that last new wave of JWA footage in 2019. -

Have you seen the 1980 Jumbo/Bock AWA match? It's more heavily clipped than the others (from 20:05 to around 14:45), but it's at the very least novel in that it's the only one we have between them on Bock's home turf, and which has Heenan as a factor.

-

I started this as Part Two of the SWS history posts, but there is no way that I could do justice to the fracture of the Newborn UWF, and consequent formation of Fujiwara Gumi, while packing it in with the next main part of the narrative. I promise not to go all Kingdom Hearts on you guys with interquel after interquel to put off proper sequels, but sometimes you need to spin chunks off into separate pieces for your own sanity. This is primarily sourced from a 2018 Igapro article. The Dissolution of Newborn UWF ------------------------ After his victory over Masakatsu Funaki in the main event of UWF Atlantis on October 25, Akira Maeda, the company’s biggest star and the cofounder of its revived incarnation, made comments to backstage reporters. The gist of these, from what I was able to gleam through DeepL, was that Maeda believed that the performances of Nobuhiko Takada and Kazuo Yamazaki (the latter of whom did not work UWF Atlantis) were compromised by “being in an environment” where they could not concentrate fully on their fights. Maeda stated his intent to protect his younger talent in that sense, and declared that any force which attempted to interfere or meddle with them, be it from outside or within, would be crushed without mercy. Four days later, UWF president Shinji Jin made a surprise announcement that Maeda would be punished for his damaging comments with a five-month suspension. This executive decision had been made with no input from the rest of the board. Meltzer’s breakdown of the tensions between Maeda and Jin which led to this, which he published at the head of the November 12, 1990 Observer which reported on Jin’s announcement, states that they started in March 1989, when Jin handed Maeda a contract, with a clause “that is in all wrestlers’ contracts in Japan”, which read that he would have to pay twice the amount of the contract itself in order to break it. Maeda did not sign it. Meltzer reported that Maeda and Jin, who had known each other since Jin had worked in the NJPW front office in 1983, were such close friends that Maeda had never worried about business affairs – which were left entirely in Jin’s hands, even if the ownership of the Newborn UWF was a five-way split between the two of them as well as Takada, Yamazaki, and managing director Suzuki (I only have the surname at present) – and had not even wrestled under contract for the promotion until this. However, the 2018 Igapro article this is mostly sourced from ties this thread back even further. On August 13, 1988, after the company held its third event (UWF The Professional Bout), Maeda was approached by his karate teacher and mentor Shogo Tanaka, who wished to look into the company books. It doesn’t state whether Jin let him (I doubt it), but either way, there were definitely suspicions on Maeda’s end regarding company finances before the tensions began to be exacerbated due to Hachiro Tanaka. The aforementioned Observer reported that Jin felt obligated to send Yoshiaki Fujiwara, Masakatsu Funaki, and Minoru Suzuki to work SWS shows. On top of his sponsorship of Newborn UWF, Tanaka had footed the bill for the penalty fees attached to Funaki and Suzuki’s NJPW contracts. This was, as anyone familiar with the then-legitimate reputation of this era of shootstyle can guess, absolutely unacceptable to Maeda. This was not a matter of pride or some romanticized ideology; Maeda was absolutely correct to object as he had, because the perception of Newborn UWF’s legitimacy was contingent on its insulation from the rest of the professional wrestling industry. A subsequent request from Maeda to look into the books was denied. As Meltzer reported, Maeda hired an accountant and lawyer in response, with serious intent to depose Jin before he was suspended. Jin assigned Fujiwara to organize the talent on Maeda’s behalf for the next event, UWF Energy in Matsumoto on 1990.12.01, and a meeting was scheduled to determine the card. However, Fujiwara was absent from this meeting, as were Takada and Yamazaki. Fujiwara no-showed because he didn’t want to get involved in anything messy, while Takada and Yamazaki did not attend because, if they entered the Matsumoto show, that meant that they were implicitly approving of Jin’s executive overreach in suspending Maeda. Jin responded ruthlessly, claiming that they would have to pay a penalty fee four times (!) their salary if they boycotted. Of course, Jin was really planning to drive out Takada and Yamazaki as well as Maeda, and functionally replace them with the young Funaki and Suzuki. [2021.04.20 addition: according to the November 26 Observer, Fujiwara had creative differences with Maeda's ideals and wished to bring more traditional wrestling elements into the company's product.] However, Funaki and Suzuki were no great fans of Jin themselves, and in a discussion with fellow wrestler Shigeo Miyato came to the conclusion that “if Maeda is not wrong, it is not right for him not to participate [in the Matsumoto event]”. Takada agreed with them, and the four secretly met with Maeda, convincing him to attend the event. This led to a pretty famous moment, if one that was deeply ironic in retrospect. After Funaki’s defeat of Ken Shamrock, then professionally known as Wayne Shamrock, in the main event, he called Maeda up to the ring, and the rest of the locker room followed to shake hands with him one by one. On December 7, 1990, Jin announced the dismissal of all Newborn UWF talent and his withdrawal from the industry to become a concert promoter. [1] As reported in the Observer ten days later, Jin was going to prevent them from using the UWF name in their new endeavors, but for now, worries that a messy legal case would expose the UWF were abated. It was expected that they would reconfigure as a new company and reach a television deal with WOWOW. However, tensions within the promotion would prove its undoing. Maeda thought that all the wrestlers were united with him. But, if DeepL is steering me right, it seems that tensions emerged from his having met with Takada and Yamazaki beforehand to coordinate a meeting. Fujiwara and Tatsuo Nakano did not appear at this meeting. Fujiwara had already received his invitation from Megane Super to form what would become PWFG, but did not want to negotiate to pull Funaki and Suzuki out with him, so he withheld his answer to Hachiro Tanaka while taking a step back from the situation. Nakano, meanwhile, didn’t want to get involved in something he predicted would get messy, because he knew about the discontentment of Shigeo Miyato. Miyato was disgruntled by Maeda using Takada and Yamazaki as liaisons to arrange this meeting, as he claimed he was the one who arranged the unity, and that he should therefore have the right to speak. This snowballed into an argument where Miyato accused Maeda of treating him like he was still his little apprentice. In response, Maeda told the wrestlers to disband as an attempt at “shock therapy”. If the translation is coming out correctly, Takada at least understood what Maeda was trying to do, but nevertheless the wrestlers began moving “according to their own agendas”. The first plan, which Miyato, Yuji Anjo and others moved towards, was to establish a promotion centered around Funaki. Funaki, who felt that Maeda had abandoned him, went with Suzuki to talk to Fujiwara about their plans, and it was at this point when Fujiwara accepted Megane Super’s offer. Funaki tried to invite some other UWF talent to join, but Miyato refused because he did not want any sponsors. At this point, Miyato moved to form what would become the UWFi, centered around Takada. As written at the beginning of the paragraph, Takada understood that Maeda had just been trying to splash some figurative cold water in their faces, but he ultimately went along with this plan because he felt obligated to take care of Miyato, Anjo, and the others, but also wanted the chance to be the ace of a promotion, which he would never become over Maeda. Maeda, for his part, realized the error he had made, and visited Funaki’s house in a last-ditch attempt to at least salvage him. But Funaki was not there, and even if he had been, he would not have agreed to a meeting. So it was that the Newborn UWF splintered into the UWFi and PWFG, leaving Maeda, for the moment, alone.

-

If you want some more info about the Toyonobori era of the JWA, and an interesting tidbit about this match specifically, I have a post in my puro history thread to pimp.

-

I can't say I know about any specific incident but I do know that the Ishingun era in general was a deeply frustrating time for AJPW's foreign crop.