-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

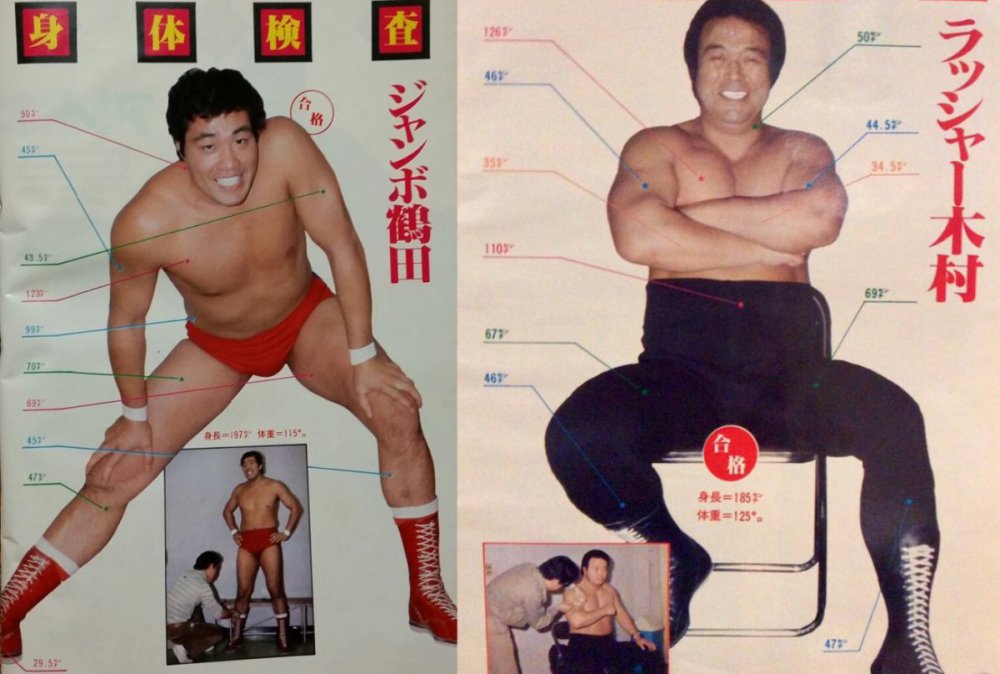

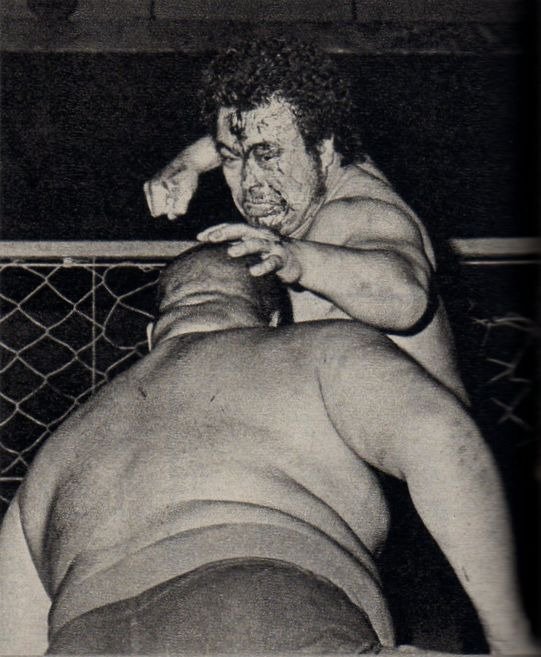

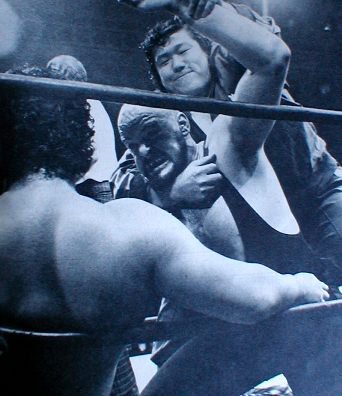

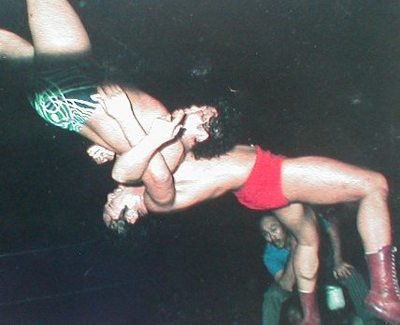

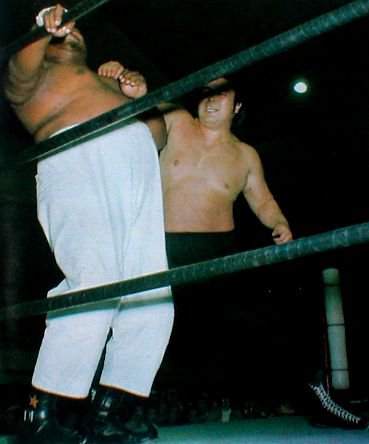

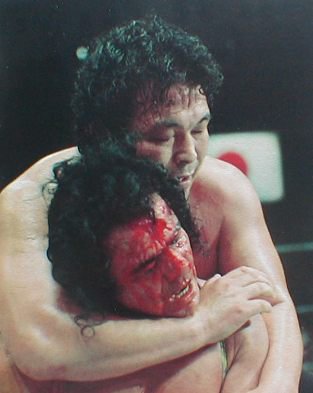

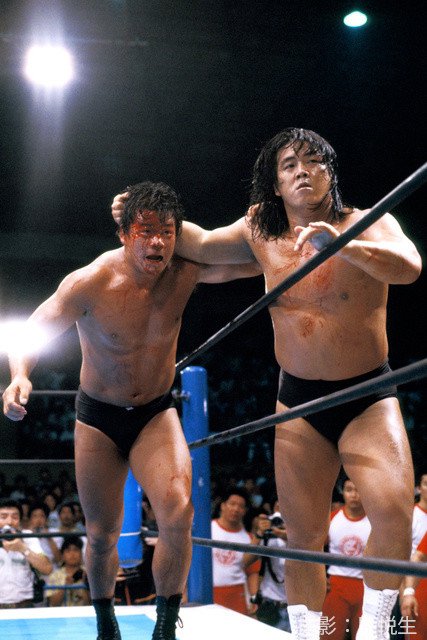

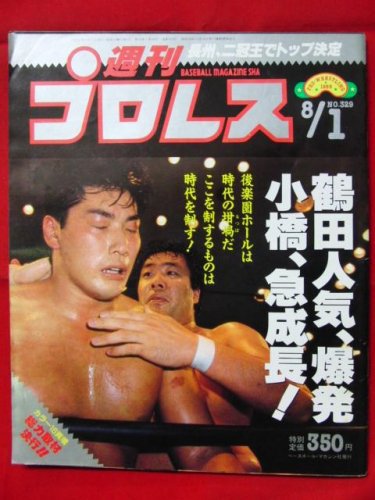

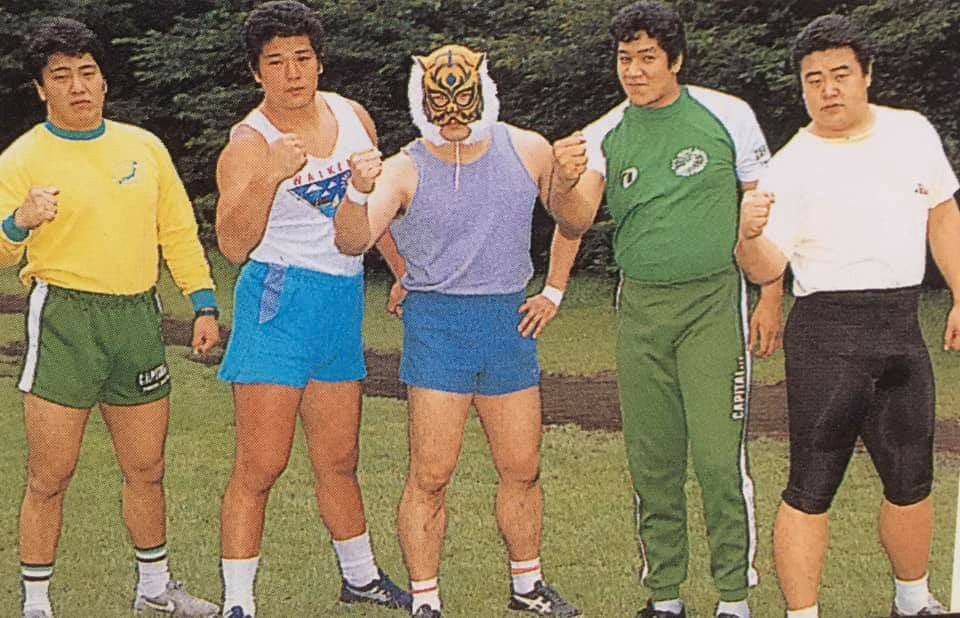

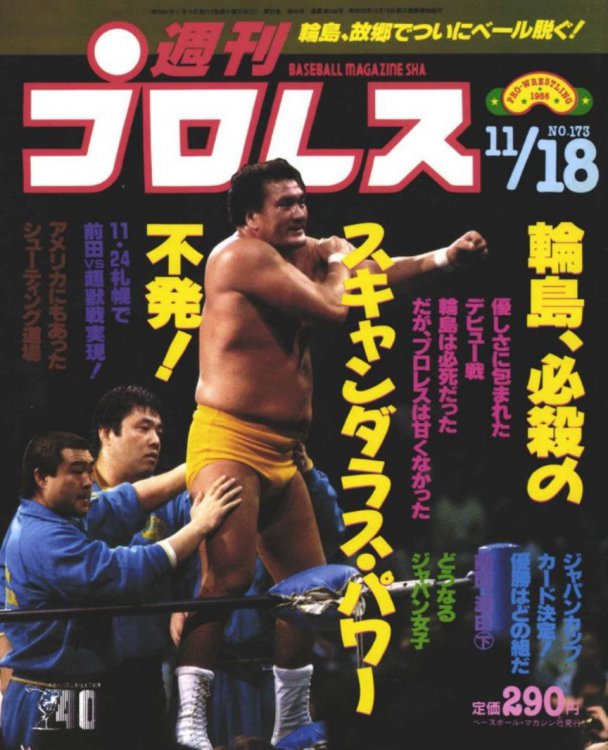

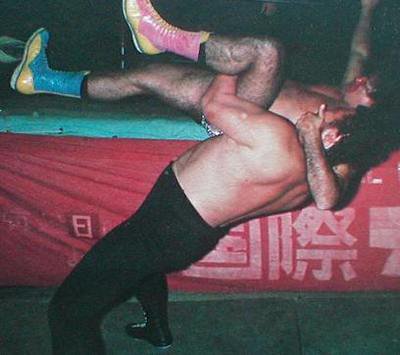

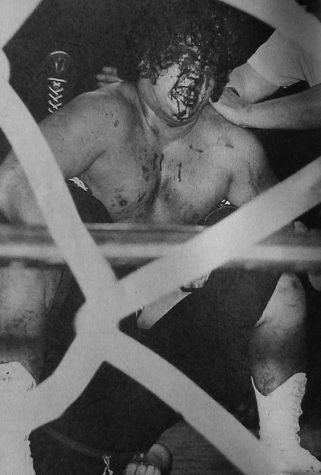

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 10-17, PART TWO (BATTLE LINES AND SHIFTING TIDES) Above: Tsuyoshi Kikuchi, Mitsuharu Misawa, Toshiaki Kawada, Kenta Kobashi, and Akira Taue at Ichinomiya beach, August 1990. [Weekly Pro Wrestling, Issue #392 (8/21/1990)] As covered at the end of the post at the top of this page in the thread, the Great Kabuki was the last in a string of AJPW departures connected to the formation of SWS. The day after the Summer Action Series tour had ended, the then co-world tag team champion turned in his notice. On August 1-4, the younger wrestlers held a training camp under Baba’s supervision at Ichinomiya beach. Misawa, Kawada, Kobashi, Taue, and Tsuyoshi Kikuchi were joined by trainee Satoru Asako; Yoshinari Ogawa would have shown up as well, were he not still on the shelf from elbow surgery. They brought training equipment (and Taue had to drive back to Tokyo to get proper footwear after arriving oblivious in flip-flops), but the primary aim was to increase unity.[1] Tokyo Sports reportage tentatively dubbed the group Misawagun, and Ichinose followed suit in his earliest coverage. The failure of Kekkigun was still fresh, but this new group was marked early on by Misawa’s firm refusal to act as a leader for the group. After all, that had been the undoing of the earlier faction. At this juncture, though, the extent to which native vs. native programs would play into the company product was still uncertain viewing from the outside. In his contemporaneous coverage of the training camp, Ichinose pointed out that there may be a point where Tsuruta might need to work with Kobashi or Taue against a major foreign team [Author's note: for reasons of cultural and linguistic sensitivity, I've recently decided to wean myself off of the standard use of 'gaijin' in my writings, either for 'gaikokujin' or other verbiage] in for practical purposes, or even wrestle alongside this group. He was, at least, correct about one of those things, albeit to a greater extent than he realized. However, there was no angle that tied into Taue’s switch in sides for the Summer Action Series II tour. It was a rearrangement that Baba made, obviously for the simple reason that with the departures of Yatsu and Kabuki, Jumbo only had Masanobu Fuchi and Mighty Inoue as allies. It was at this point that the Super Generation Army/Tsurutagun feud began its shift into something more complex than a simple intergenerational feud, although Yoshinari Ogawa would not return to the ring until October, and would not join Tsurutagun proper until February 1991. Speaking of Taue, he had made progress in the second half of 1989 into the new decade. But this saw him continue to work with Tenryu. In fact, half of Tenryu’s last six matches for the company (though that’s seven if you count the Randy Savage match at the Wrestling Summit) were singles matches with Taue. And while Tenryu meant well in his attempts to imbue in Taue the rhythms of pro wrestling, and work with him in a stiff manner to compel Taue to return in kind–as Tenryu had done for fellow ex-sumo Hiroshi Wajima and Isao Takagi–it was an incompatible approach.[2] Taue does not go so far as to call Tenryu abusive or openly begrudge him, but he is frank about the fact that working with him was his primary source of workplace anxiety, and that on some level he was scared of him. As established in a previous post, Taue left sumo because of the physical abuse he received from his stablemaster, so his feelings about Tenryu made sense: “He only taught me how to hit people.” Jumbo would have more to teach him. The Summer Action Series II tour began on August 18, in Korakuen Hall. In the main event, Misawa, Kawada & Kikuchi took on Tsuruta, Taue & Fuchi. It was on this night that Chosedaigun (“Super Generation Army”) was coined by AJPW commentator Kenji Wakabayashi. Ichinose actually resisted the use of the term in his Weekly Pro write-ups at first; the disappointment of the aborted generational feud in New Japan (which was part of TV Asahi’s 1987 attempt to reinvigorate a declining program) still loomed large in his mind. Tsuruta would lean further into his function as a heel in the coming days. On August 19, in an untelevised Korakuen main event between he & Fuchi and Misawa & Kawada, Jumbo *snapped* on Misawa, assaulting him with a chair and hitting three backdrops. While untelevised, photos of this incident and comments from both men in response were shown in a report segment in the middle of an AJPW TV episode, so this angle was part of the primary canon. Two days later, during a Misawa/Kobashi/Kikuchi vs. Tsuruta/Fuchi/Inoue six-man (see previously linked episode), Jumbo immediately requested a tag when Misawa hit his left ear with a flurry of elbows. Tsuruta would claim that this caused temporary deafness, but Misawa dismissed that complaint, in “spiky” post-match comments which also saw Misawa declare that Jumbo “deserved to lose” their upcoming Budokan rematch for what he had done in the Korakuen match two days before. Misawa had called the matter of the company’s ace into question, defeating Tsuruta in that unforgettable first Budokan match three days after his opponent had dropped the Triple Crown to Gordy. Of course, if one considered that Tsuruta worked in 13 of the subsequent tour’s 17 main events, while Misawa only appeared in four, it was clear which way Baba still saw the pecking order. But Misawa had sewn some doubt…a doubt which was vanquished upon Tsuruta’s dominant victory on the 1st of September (it’s not on YouTube at the moment, but it’s an easy match to find). Eleven days after winning this rematch, Tsuruta declared that he, and not the Super Generation Army, would carry the banner of “intense pro-wrestling”. “Of the goals of All Japan, which are to be bright, fun, and fierce, the fierce part has been perceived as if Tenryu is the only one who is responsible for it. But this is not true, and I have been thinking to emphasize the "fierce" part a little more deliberately in order to respond to the feelings of All-Japan’s fans. […] I might not be able to do intense matches as I get older, and if that happens, you can give way to Misawa, Kawada and the others. But until then, I will carry the intensity of All Japan.” Back in the last year and change of the 1980s, when Toshiaki Kawada had been called up to be Tenryu’s Revolution tag partner in the wake of Ashura Hara’s dismissal, Tsuruta had been clear about his own interest in helping Kawada grow. He wanted Kawada to grow up and acquire the skills to be Tenryu’s partner, because he was the company’s future. Appropriately, Ichinose recalls that in his match report for the first Tenryu/Kawada vs. Olympians match of 1989, which ended in 34:48 with a Jumbo backdrop to Kawada, that the Olympians had attacked Kawada slowly and deliberately, “as if they were teaching schoolchildren how to write kanji”. In the immediate aftermath of Tenryu’s departure, Jumbo had spoken of his intent to work with the next generation along these lines, to make them ready to face the top gaikokujin. But by the summer’s end, something had changed in Tsuruta for sure. Back in August, Baba had asked Ichinose for ideas on what to do for his 30th Anniversary show on September 30, to which Ichinose suggested a match against Andre the Giant. He doesn’t mention how Baba made it happen, but I wonder if this was one last trade that he pitched to Sakaguchi: Andre for Tiger Jeet Singh, who would team with Inoki in the main event of his own 30th Anniversary show. All Japan, for their part, would see Baba team up with Abdullah to take on Andre and Hansen. The All Japan show was held at Korakuen, while New Japan booked the Yokohama Arena. The NJPW show started at 3:00PM, while the All Japan show began at 6:30. Under normal conditions it was only a fifty-minute train ride between the venues’ respective nearest stations, but a typhoon struck the Kanto area, causing delays. Ichinose recalls a flood of exhausted photographers and reporters finally entering the venue during the semi-main event. That match was the first proper, 2-on-2 battle between Misawa & Kawada and Tsuruta & Taue. Famously, the match would go to a 45-minute time-limit draw. Ichinose makes an aside that he feels it was unlikely that both sides went all-out, as they likely wanted to be able to watch the main event, but in his match report, Ichinose’s coworker Kazuhiro Kojima claimed that he had never seen such a hot and intense time-limit draw. (This would also be the promotion’s second Wrestling Observer five-star match of the year.) On the 30th anniversary of his debut match, in which he had lost to Kintaro Oki, Antonio Inoki pinned Animal Hamaguchi in a tag match, working alongside Tiger Jeet Singh, the first foreign heel that New Japan Pro Wrestling made an icon, against Hamaguchi and Big Van Vader, the definitive gaikokujin of the promotion in the present. On the 30th anniversary of his debut match, in which he had defeated Yonetaro Tanaka, Giant Baba did not even factor into the final result of his respective tag match. Rather, Andre the Giant pinned Baba’s teammate, Abdullah the Butcher, in 10:13. As Ichinose puts it, Inoki rode a horse which his Three Musketeers had made with their fighting spirit, while Baba quietly resisted the spotlight. It’s also worth noting that this show happened to have been held one day after SWS’s first event. In his September 12 interview with Ichinose, though, Tsuruta was fully confident that he and All Japan would be vindicated in the end. “I think the conclusion will come in 5 years or even 10 years. From now on until that conclusion is reached, I will work hard to be better than the wrestlers who went to SWS in every way, socially, humanly, and of course in terms of treatment, so that I can say, ‘I'm glad I stayed in All Japan after all.’” The immediate reception of the match may as well have been a response to Tsuruta. For when the semi-main was over, the Korakuen crowd did not just chant his name, nor the name of his partner or even those of his opponents. They chanted “Zen Nippon”. --------

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 10-17, PART ONE My summaries of Part Two (Chapters 10-17) of the Pillars bio begin here. I settled into a two-chapters-per-post groove early on in these recaps, but I decided to transcribe some more this time before posting again. Part of this was psychological; the time when this process drains me most, outside of especially long chapters, is when, having finished a recap, I have to start from square one of a whole new chapter. But the thing about this book (particularly compared to Osano’s Jumbo bio) is that it likes to subsequently bring up details that I often wish I’d had at my disposal when writing a previous recap. I must have come to get down, because Ichinose loves to jump around. Another factor is purely personal; I will be spending Labor Day week in Vegas for my cousin’s wedding, so I wanted to work extra hard on transcription to compensate for time that I very much intend to devote to myself and to my family. The next few posts, which I will spread out over the next few days so that I can polish them, will span chapters 10-13 (I haven’t finished transcribing 13 yet, but it’s not that long and I know that it ends in April 1991, like the rest of the chunk I’m covering), but due to my approach this time I’m switching around the order of topics in a way that doesn’t represent the order in which Ichinose brought them up. For instance, this post about Tsuyoshi Kikuchi is mostly based on information in chapter 12, which jumps back to the 80s in the middle of a bunch of stuff set in early 1991. That’s why, for the next few posts, I will be titling them differently in my Table of Contents Google Doc for this thread, like so: “Chapters 10-13, Part 1”. --- THE BIRTH OF THE FIREBALL BOY Above: Weekly Pro Wrestling coverage of the debut singles matches of Tsuyoshi Kikuchi (against Mitsuo Momota) and Kenta Kobashi (against Haruka Eigen) on February 26, 1988. [Issue #248 (3/21/1988)] Tsuyoshi Kikuchi was born in Sendai on November 21, 1964. Like many an All Japan recruit, he didn’t see his father much in his early life, but this was the case of a working man rather than a broken home. Tsuyoshi had a vague aspiration for police work in his youth, motivated by his sense of justice and duty as an eldest son to protect a vulnerable mother. Kikuchi’s motive for joining the wrestling club was impure, but charming in its naivete. He didn’t get in to impress a female classmate, though; rather, he had his eye on recently retired figure skater Emi Watanabe, an eight-time national champion who had won Japan its first womens’ medal at the 1979 World Championships. Tsuyoshi figured that if he became a top amateur wrestler, he could go to Tokyo and “get close to her”. The crush didn’t last long, but he found that wrestling suited him. “I imagined myself doing such a hard thing, such a good thing, and I got drunk on it.” It wasn’t until his second year of high school that he became interested in professional wrestling. It should not surprise you that New Japan caught his eye first, nor that Tiger Mask and particularly the Dynamite Kid were responsible for getting him hooked. He would later state that what attracted him to Kid was that “he had such a great power that he made you feel it was ok even if he blew himself up” (to be clear, Kikuchi meant that in the sense that Dynamite was like a bomb). He was interested in becoming a pro wrestler upon his graduation, but his parents persuaded him to continue his studies at Daito Bunka University. It was here that Kikuchi began to watch All Japan, whose junior division caught his eye. After Atsushi Onita lost his first retirement match against Mighty Inoue on December 2, 1984, Inoue said something to the effect that, if Onita wanted to return, he’d be willing to wrestle him anytime. His words “shook Kikuchi’s heart”, and the transfer of the British Bulldogs to the company further compelled him. The deciding factor, though, was Jumbo Tsuruta. Kikuchi’s wrestling team captain was an old acquaintance of Tsuruta’s from his collegiate wrestling days, and he asked for an introduction. As covered in a much earlier post in the thread, he was told that due to his size, he could only feasibly join All Japan if he won a national championship. At this point, Kikuchi weighed less than 85 kg, but he went up two weight classes to compete in the 100kg freestyle class. By his senior year, four-time division winner and future AJPW/NOAH coworker Tamon Honda had graduated, so in August 1986, Kikuchi won student nationals. He attended an AJPW Korakuen show soon afterward to meet Tsuruta and state his intent. He submitted his resume to the office, to no reply. Eventually he made the trip to another Korakuen show: that of March 24, 1987. The Japan Pro Wrestling boycott was in swing, so the show was understaffed backstage. Kikuchi ended up getting a job because there were no trainees to perform chores. The following week, he began training camp and was assigned as Tsuruta’s valet. Alongside Kenta Kobashi and Tatsumi Kitahara, he was known as one of the “three crows” (Japanese expression) that made up the new crop of trainees. It would take Kikuchi ten months to make his official debut. Despite his amateur success and conditioning, Kikuchi struggled deeply with this early training. The stress brought upon a case of gastritis two months in. However, Kikuchi would make his unofficial debut at the end of the year, as part of a ten-man battle royal at the Haru Sonoda memorial ceremony. Two months later, he made his singles debut on February 26, 1988, on the same night as Kenta Kobashi. However, his fellow crows would “flutter far ahead” in 1989: Kitahara abroad to work for Stampede, and Kobashi into the Asunaro Cup and subsequent upper-card work. Meanwhile, Kikuchi was stuck curtainjerking with Mitsuo Momota. Like Kawada before him, however, Kikuchi would later express gratitude for the time he spent on the bottom, with great praise for Momota as a mentor. His trademark Hinomaru tights, which he would adopt at the start of the new decade, were an aspirational nod to the British Bulldogs’ use of the Union Jack. On the first two dates of a three-night string of Korakuen shows at the end of the New Year Giant Series tour, Kikuchi would get to work alongside and against his idol. First, on January 26, he wrestled Dynamite in a singles match, losing by pinfall in 3:47 after a diving headbutt. The following night, he won a six-man tag with the Bulldogs against the Fantastics and Masanobu Fuchi. Even with the debut of Masao Orihara in February though, Kikuchi remained an undercarder in the coming months. The SWS exodus would change that. On June 30, 1990, All Japan held a special Korakuen event a week before the start of the Summer Action Series tour. An understaffed heavyweight division thrust Kikuchi into the main event, a six-man tag in which he wrestled alongside Mitsuharu Misawa and Akira Taue against Jumbo Tsuruta, the Great Kabuki, and Masanobu Fuchi. At 5’10” and 202 lbs. (177cm; 92 kg), Kikuchi was an unattractive wrestler in the eyes of the first component of Baba’s wrestling philosophy, primarily centered as it was around “the clash of big bodies”. However, in a starmaking performance, with face swollen and nose bloodied, Kikuchi fulfilled the second half of Baba’s philosophy, in that he “[did] things which ordinary people cannot do”. In a January 1988 Weekly Pro interview, Tsuruta explained that he adjusted the angle of his backdrop depending on the wrestler he was facing. If he was wrestling a Jumbo or a Choshu, he was confident that they could take the stiffer variation, and so he would administer it. However, he admitted that his nature was too gentle to go all-out all the time, and stated that there should never be a situation in which a wrestler has to be hospitalized. As I believe I have covered elsewhere, Jumbo always considered himself by nature to be the technical, “horizontal” wrestler that he was trained to be in the 1970s, and that his work in a more Japanese vs Japanese “vertical” idiom was a reactionary impulse. In other words, you had to be the one to provoke him, as Tenryu often was, and as Misawa had. But on this night, as the company ethos of “intense pro-wrestling” seemed to be in jeopardy in the wake of the SWS exodus, Tsuruta delivered a then-uncharacteristically violent performance that made Kikuchi’s babyface appeal shine. [This match appears to have been out of circulation for a long time, but Roy Lucier recently uploaded it on a rough but watchable rip of a commercial tape.] "It's up to Misawa and the others to show something different about themselves every day, and I'm just going to do my best for the moment. I don't try to do this or that, I just try my best to connect and stay until the end. My style is to be the receiver, not the aggressor." Kikuchi would never be a true main eventer. He wasn’t even really the junior that Baba had wanted: more Billingston than Sayama, you could say. As Ichinose puts it, in getting this spot in the Super Generation Army Kikuchi got his Cinderella story…but his foot was too small for the glass slipper. In an interview for this book, though, Tsuyoshi claimed that he only had one regret; he never got to take the Western Lariat. On September 1, in a famous match with Joe Malenko against the Fantastics (part of a tournament for the vacant All Asia tag titles), Kikuchi suffered a ruptured testicle when the back of Tommy Rogers’ head accidentally hit his groin on the landing of a Doomsday Device. [1] After surgery, he returned in November. In an August 1990 Weekly Pro interview, Kikuchi said that he wanted to be the Keith Richards of pro wrestling. That’s not important, it’s just something I wanted to share.

-

[1987-06-12-NJPW] Antonio Inoki vs Masa Saito

KinchStalker replied to Superstar Sleeze's topic in June 1987

This was to be the start of an (ultimately aborted after Maeda's departure) intergenerational feud, as part of the initiative taken by TV Asahi (see spoiler tag below for a digression on the other component of their campaign) to reinvigorate the declining TV program. The Ganryujima match wasn't something that was proposed until August (interestingly, it was originally an idea that Fujinami had had for his first match against the returning Choshu, but Inoki aide Tetsuo Baisho told Inoki about the idea), when Inoki stated that, rather than fighting the new generation, he wanted to "fight the ultimate fight that only [he] and Saito could do," and show their strength "not only to Choshu and the others, but to the network that wanted to put [him] down". The heat between Inoki and Saito would get turned back up in the 9/17 gauntlet match. -

[1987-03-26-NJPW] Antonio Inoki vs Masa Saito

KinchStalker replied to Superstar Sleeze's topic in March 1987

I browsed the Japanese internet to see if I could be of assistance. NJPW referee Mr. Takahashi wrote a kayfabe-breaking autobiography-cum-expose about his time in New Japan a few years back, and if we're to take him at his word, the pirate man (played in this instance by Black Cat) messed up and handcuffed the wrong guy. If it's any consolation, you weren't alone in your dissatisfaction. 35 cops, five fire trucks, and two ambulances were dispatched to quell the riot that ensued. -

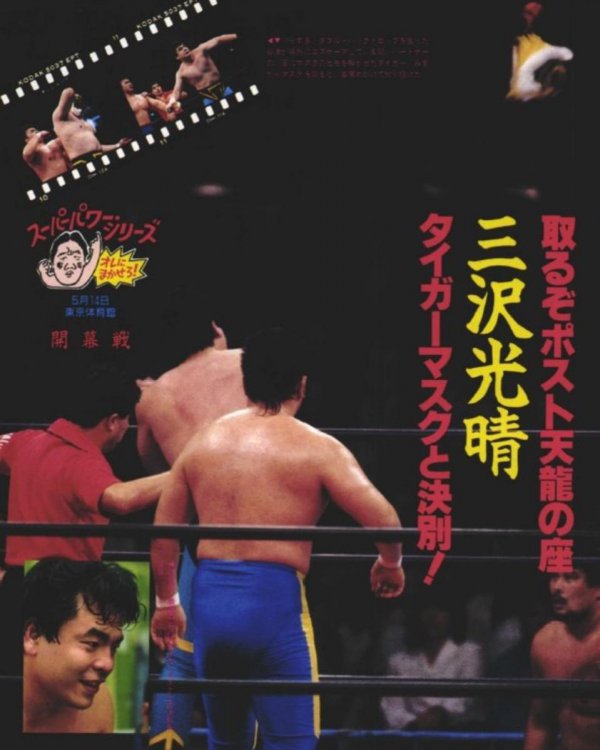

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 1-9, PART FIVE I crushed my finger closing a cot during a camping trip (no bone or nerve damage, but still painful), but that didn’t actually hurt my workflow much. Most of this transcription work is pressing CTL+C->CTL+V, after all. Anyway, here’s what I’ve gleamed from Chapters 8-9. ---------- “There was a time when I used to think that [that was] the way it should be. But now I've changed, and I'm thinking, "This is better.” In a sense, I used to be a professional wrestler. I used to cheat my fans and do whatever I could. But now, I think that I won't cheat my fans anymore.” - a roughly translated remark by Baba, during a 1990 Weekly Pro interview with Tarzan Yamamoto Chapter 8 gives some context than the Jumbo bio didn't about the backstage frustrations which must have influenced Genichiro Tenryu to leave for SWS. It does not appear that he nor the rest of the company’s talent knew at this point about the meetings Baba was having with the Weekly Pro guys, but Tenryu sure sensed the change. Ryu Nakata told the author back then that, on the March 1989 Korakuen show when Baba & Kobashi wrestled for Footloose’s All Asia tag titles, Tenryu could be heard muttering “who the hell put this match together?” Ichinose recalls that he was not allowed to approach Tenryu and notify him of what was happening in advance, as his duty was to remain in the background. That year, Tenryu also expressed irritation with his tag team with Stan Hansen. He saw his style of wrestling as a two-way street, and was frustrated by the styles clash that the very one-way Hansen presented. In a section which turns back the timeline to 1987-88, Ichinose recalls, among other things, how he was compelled by the Tenryu Revolution. Still, he believed that, no matter how wonderful the contents of a match, if the result was uncertain – as it was in the third Jumbo/Tenryu match – All Japan had no future. We also get a bit more insight into how AJPW was covered by Weekly Pro. Despite the secret involvement of its staff in the promotion’s creative shift, All Japan did not receive disproportionate coverage in their magazine. On the contrary, while higher-quality shows would naturally give them more coverage, they did not receive the luxury of special issues for their biggest matches, unlike their competitors. This was the decree of the sales division, who did not believe that All Japan special issues were commercially viable. There’s one important piece of info from Chapter 6 that I skipped over in its respective recap post, because it happened a bit further along in the timeline. Now it’s time to address it, although if you’ve been reading Matt D’s 1989 AJPW watchalong thread over on DVDVR, I already dished on it. The AJPW vs NJPW match of Genichiro Tenryu & Tiger Mask II vs. Riki Choshu & George Takano at the 1990.02.10 Tokyo Dome show wasn’t the original plan. As the card was first announced on January 24, Tenryu was set to team up with Kawada, and Choshu was to wrestle alongside Kuniaki Kobayashi. In the coming days, though, Choshu decided to switch Kobayashi out for George Takano, which NJPW president Seiji Sakaguchi was reportedly quite unhappy about. On February 5, it was announced that Kawada would be snubbed to make room for Tiger Mask II. When it comes time to cover Tenryu’s last show before leaving AJPW, Ichinose does not offer nearly as much insight as the Jumbo bio did. However, he does make a personal observation that, while he believed Tenryu still had a role to play in the revitalization of the company, he surmises that Tenryu felt that his job was over in light of Baba and Yamamoto’s efforts. (This implies that Tenryu knew of Weekly Pro’s creative influence at this point, but there’s nothing I can find in the text that confirms this one way or the other.) The first show without Tenryu was the May 14, 1990 show at the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium. Ichinose notes that many matches had taken place here, most notably the May 24, 1963 Rikidōzan-Destroyer match, but that this was the first wrestling card to have been held at the venue since renovations had begun three years earlier. Ichinose recalls that the atmosphere of the show never congealed into a hopeful one. Above: Mitsuharu Misawa unmasks after nearly six years. [From Issue #380 of Weekly Pro Wrestling, 6/5/1990] Famously, Tiger Mask II unmasked in the antepenultimate match. Ichinose disputes that this directly correlated to Tenryu’s departure, as he had actually told a Weekly Pro reporter in March about his intent to unmask. He concedes that it was a great moment, but notes that the semi-main event, in which Davey Boy Smith wrestled Dustin Rhodes (billed here as Dusty Rhodes Jr.), was one of the most mediocre AJPW matches of the decade, and completely failed to maintain the crowd heat that the ray of light that was Misawa’s unmasking had finally given the show. The main event, in which Giant Baba and Jumbo Tsuruta reunited as main-event tag partners for the first time in years (Yoshiaki Yatsu hadn’t left the company at this point, but had been injured in his March singles match against Steve Williams), saw Baba get pinned clean by the Miracle Violence Connection. This didn’t do much at all to help the mood – with a moment where Baba collapsed “as if electrocuted” when Gordy whipped him into the corner being an especially bleak one – but there was one significant symbolic detail to the whole affair. When it came time for Ryu Nakata to announce the native participants, he announced Baba’s name first, an admission that Jumbo was the top dog now. Boy, no wonder Jumbo took the Misawa loss as such an existential threat. On their way back to the Capitol Tokyu Hotel for a meeting, Yamamoto and Ichinose weren’t optimistic about the company’s prognosis. There seemed no surefire way for AJPW to recover. Without Tenryu, the intensity of “bright, fun, and intense pro wrestling” was all gone, as the show had plainly displayed. They quickly agreed, however, that Misawa was the only chance they had. During the meeting, they told Baba that Misawa was the only way to go. Baba was quite reluctant. For all the implications of the ring announcement before the match he had just worked, he was still thinking in that old mode of seniority-based hierarchy. The way forward seemed to him to be as it has always been; a challenge for the ace against a gaikokujin at the end of the tour. His consultants were firm in their conviction, though, and while Ichinose cannot recall exactly what he said to make Baba agree in the moment, he remembers that he at least got that out of him. Regardless, Tsuruta vs. Misawa would not be announced as the tour’s final match until the May 26 Korakuen date. Shockingly, Ichinose recalls that Shunji Takano, and not Misawa, was slated for the main event of this Korakuen date, but injury changed those plans, and the six-man tag that we all know and love as the pre-coming out party of the fully-formed Misawa was allowed to happen. Chapter 9, and by extension the first part of the book, ends with a bit of information about the June 30 One Night Special in Korakuen and the following Summer Action Series tour. Ichinose notes that he considers the former show’s semi-main event, a singles match between Kawada and Kobashi, to be Kawada’s “starting point” as a fully formed wrestler. Ichinose then moves to the subject of Yoshiaki Yatsu’s final tour for All Japan. He recalls the brawl that he and Misawa got into during a Misawa/Kawada vs. Olympians match, and also addresses a rumor that’s circulated on the Japanese Internet that, during a house show, Misawa and Kawada pulled a Tenryu and took it to Yatsu (not in an “beat to a pulp” way, more a “stiff the guy to motivate them to return in kind” way) after the man had said they could cut corners for the provincial crowd. Ichinose excerpts an interview from 1998 in which Yatsu remarks that, as he'd instructed both Misawa and Kawada during their days at the Ashikaga Institute of Technology high school, that it would've been a pity if he hadn't left, as they still would've called him "Yatsu-senpai" and had held back as a result. (It reads to me as an unconvincing, "Sure, Jan"-worthy statement, but whatever helps get that guy through the day with all the bridges he burned in the business.) On July 19, after Yatsu had already left, Jumbo and the Great Kabuki won the AJPW World Tag Team titles from the Miracle Violence Connection on a televised B-show, as a new “veteran duo” after Yatsu’s departure. Alas, Kabuki himself bounced for SWS at tour’s end. On July 30, he turned in his notice to Baba.

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

Misawa tried as hard as he could, to the deficit of NOAH's resources, to keep people hired and continue the family culture that he had known in All Japan. As we all know, the less idealistic people in the company won out and made cuts after his death. Morishima fell the hardest, though it took a while for him to bottom out. NOAH wasn't just his job, it was his entire support system, and his case makes the failure of Misawa's late-life plans to develop some sort of vocational rehab program for his wrestlers (as well as to build a steakhouse, which his widow got defrauded for when the Yakuza wife who'd been sponsoring NOAH claimed she would finally make it happen) especially painful. -

This catalog is the closest thing I can think of. ClassicsPuro83 uploads are ripped from domestic DVD sets, though.

-

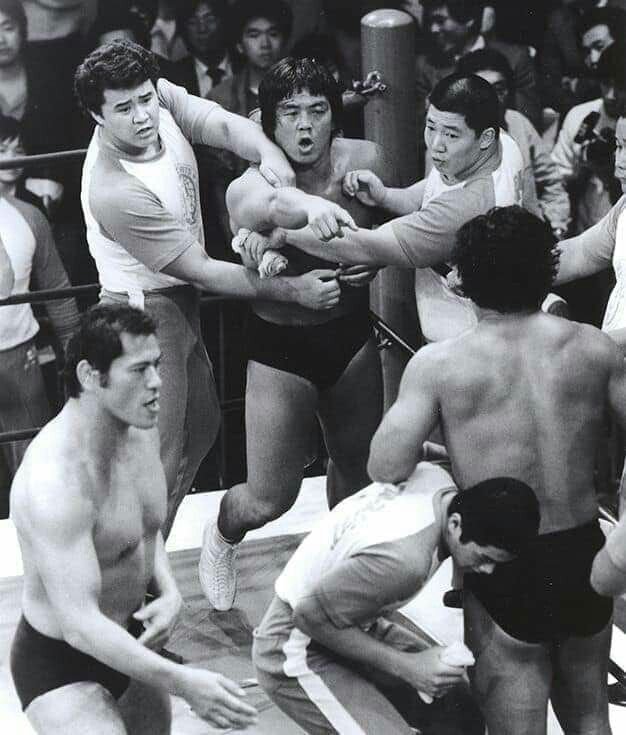

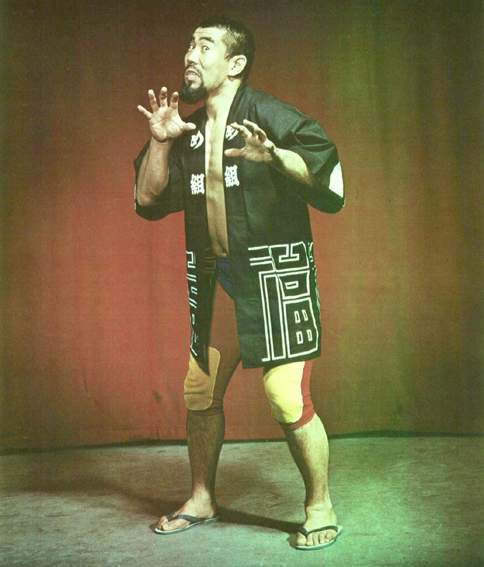

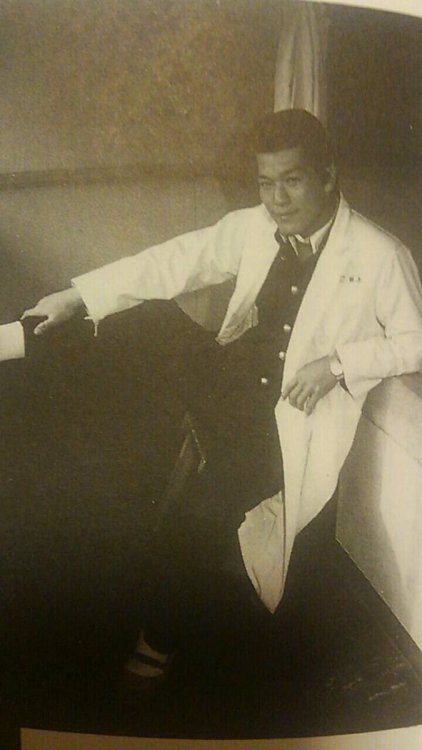

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 1-9, PART FOUR (KEKKIGUN AND THE ASUNARO CUP) Sorry for the slowness. I transcribed over 60 pages this time, deciding to bundle Chapters 6-7 together after the first wasn’t as meaty as I wanted it to be. Personal engagements, existential dread in the wake of my 25th birthday, and the malfunction of my laptop keyboard also contributed to delays. Broadly, these chapters are about the struggle of the younger generation to break through in All Japan in the late 80s. They both essentially cover the same stretch of time from different angles, so I’m not going to bother with splitting them up in my recap. (There's a little bit of stuff it covers later in the timeline, which I skipped for the next post in order to keep things cohesive; I wanted to keep this post strictly 80s.) --- This stretch of the book starts with Misawa’s frustrating transition to the heavyweight division. His seven-match Trial Series was set to begin in July 1986 with a match against Ric Flair, but Flair’s bookings were cancelled and Yoshiaki Yatsu, who had ranked seventh in the fan poll (one spot below Flair), was put in his place. Then, his second match in the series was booked to be against Ashura Hara, but Hara couldn’t reach the venue in a snowstorm and gaikokujin-of-the-tour Frank Lancaster was subbed in his place. By his August 1987 victory over Ted DiBiase Misawa was 3-3, but as contemporaneous Weekly Pro coverage put it, “DiBiase was suffering from WWF Syndrome […] and lost the match without a care in the world”. The final match of the Series, against Jumbo Tsuruta, ended up being delayed for the better part of a year due to the Tenryu Revolution, and in the meantime, Tiger Mask II lost his spot as Jumbo’s tag partner to Yoshiaki Yatsu. The Olympians would win their only RWTL as a unit in 1987, while TM teamed with Yatsu’s old JPW partner Shinichi Nakano in a mediocre 3-7-1 performance. On March 5, 1988, four days before the final Trial Series match, TM attacked Tsuruta after his singles match against Jerry Oates. His comments to the press in the waiting room denied that he was splitting from Tsuruta outright, and the author notes that this outburst was something that the future Mitsuharu Misawa would never have done. TM got his match against Jumbo, and it was a good one, but he lost in 14:38. Tsuruta commented afterward that “Tiger can do anything; he just needs to perfect his rhythm.” Above: Kekkigun (“Rising Army”) was a short-lived faction of midcarder talent led by then-masked Mitsuharu Misawa, an oft-forgotten predecessor to Chosedaigun (“Super Generation Army”). (Left to right: Shinichi Nakano, Akira Taue, Tiger Mask II (Mitsuharu Misawa), Shunji Takano, Isao Takagi). That June, Tiger Mask II formed Kekkigun (“Rising Army”), a five-man faction of native midcard talent which sought to prove their mettle to Tenryu’s Revolution. Isao Takagi and Akira Taue were then, alongside John Tenta, the latest young ex-sumo talent that All Japan had recruited. Shinichi Nakano was the faction’s lone junior heavyweight, and had been among the few JPW personnel to remain with All Japan in the wake of Choshu’s u-turn back to New Japan. [1] Finally, Shunji Takano had been among the Calgary Hurricanes who controversially transferred to AJPW in 1986, and was the only one to stick with the company beyond his obligations. At 200cm, he was the tallest native talent in the company barring Baba, and while I’ve never been a huge fan of his work, if framed in his proper context it is understandable why he was considered a top prospect. Kekkigun was a frustrating enterprise, which you might have been able to infer since, while its spiritual successor Chosedaigun (“Super Generation Army”) is common knowledge to Western puro fans, I am willing to bet money that you hadn’t heard of Kekkigun by name until this thread. The faction unofficially debuted on June 7, 1988, in an six-man tag between Tiger Mask/Nakano/Takano and Tenryu/Hara/Kawada. Cagematch doesn’t even have the complete card for this show! Their televised debut came two days later in Kiryu, a six-man with Takagi in Takano’s place which Tenryu won with a cobra twist to Takagi. Their first match under the Kekkigun banner was at the start of the following tour, with Tiger Mask teaming up with Taue against Tenryu & Hara in Korakuen on July 2. Taue lost to a Tenryu sleeper hold, after which Tenryu coldly berated him: “You don’t know anything, and you don’t show any technique.” In contrast, Tenryu would praise Takagi for his progress made two weeks later. On August 20 in Korakuen, the next tour began. Kekkigun, this time in the configuration of TM & Takano, wrestled Tenryu & Hara. Before the match (timestamped), Hara took the mic to provoke Shunji: “Hey, Takano. You’re a big guy, so don’t be a pussy.” Takano would job to the Tenryu powerbomb in 14:21, after which he prostrated in the ring with tears of frustration. Five days later, in Yoshikawa, another tag was booked with Taue in Takano’s place, which ended in the bloodied ex-sumo eating Hara’s Hitman Lariat for the pinfall. Taue showed some progress, but it wasn’t enough. On September 1, during a show in Kurayoshi, Tiger Mask injured his left knee on a diving plancha in a tag match alongside Nakano against Johnny Ace & Tom Zenk. He was sidelined for the next three shows, returning to duty on the 7th. His ACL tear seven months later was well-known, but this knee injury continued to affect Tiger Mask afterward; “every time he fought, his knee would give out”, forcing him to put it back into place. Kekkigun arguably never recovered. TM was the only component that made the faction even register as adversaries of Tenryu. For his part, Tenryu commented in a backstage interview on September 6 that the four men needed to realize that Tiger was holding them back. Three days later, the faction achieved its greatest kayfabe success when Takano & Nakano defeated Footloose in Korakuen to win the All Asia Tag Team titles. Meanwhile, Tiger Mask would be involved in a postmatch angle after the main event. Abdullah the Butcher was disqualified in his NWA International Heavyweight title match against Jumbo Tsuruta, and TM and Jimmy Snuka followed one another to stop Abby’s assault. TM and Snuka would team up after this, and it was clear in a matter of days that they were intended to enter the 1988 RWTL as a unit. Add this to Takano & Nakano’s loss of the titles back to Footloose in Korakuen on September 15, and Kekkigun’s future was in limbo. Yet another humiliation came on October 28. In what would be his final match for AJPW, Ashura Hara faced Taue in a singles match at the end of the Giant Series tour. As Weekly Pro reported, Hara took sixteen strikes from Taue before downing the ex-sumo with only three. Hara’s dismissal from All Japan on Nov. 19 was another blow to Kekkigun’s prospects, as they had a better chance of bringing him down than Tenryu. As you all know, Hara’s dismissal led to Kawada’s appointment as Tenryu’s partner in the 1988 RWTL. In his 1995 autobiography, he stated that he didn’t know why Baba had selected him over Fuyuki despite Fuyuki’s seniority, only speculating that his greater mass than his partner at that point had influenced the decision. It had only been as a part of Revolution that Kawada had truly found a place for himself in AJPW, and his performance in the tournament was a revelation. He admitted that in the first half, he was fighting “against Hara’s shadow”, but after a December 4 tournament match against the team of Giant Baba & Rusher Kimura, in which Baba took Kawada’s offense “with his chest out”, he apparently experienced a breakthrough. On December 10, two days after his 25th birthday, Kawada faced the Olympians alongside Tenryu, and secured an upset victory with an outside dive to Jumbo and some ankle-grabbing to ensure Tenryu and only Tenryu got back into the ring before the countout. Compared to the mediocre showings put forth by the Kekkigun-adjacent teams of Tiger Mask & Jimmy Snuka, and Shinichi Nakano & John Tenta, Kawada’s work during the RWTL, culminating in one of the most acclaimed final matches in tournament history, was a shining beacon towards the company’s future. His left knee, already hurt during the tour, was exploited by Stan Hansen & Terry Gordy, and Tenryu was isolated to fall to the Western Lariat. Nevertheless, Tenryu was deeply proud of Kawada’s performance, as he expressed to reporters afterwards: “Now we just have to win.” At the awards ceremony afterwards, where Tenryu & Kawada won the Fighting Spirit Award, the crowd roared its approval. Tiger Mask & Snuka, meanwhile, made do with the Technical Award after a disappointing 3-6-1 performance. On December 27, Hiroshi Wajima and Takashi Ishikawa announced their retirements from professional wrestling; Ishikawa would return to the business in the wake of SWS’s launch, but Wajima stuck to his. Then, on January 7, 1989, the Emperor died after months of poor health. The Showa period was over, and the cultural significance of this could not help but reverberate in puroresu. Showa puroresu, as it has come to be called, was over. Around this time, AJPW got the ball rolling with the marketing campaign I covered in my previous recap. It’s worth noting here that oudou (“King’s Road/Royal Road”) was not being used as a marketing term at this point. Instead, the nomenclature used to describe All Japan’s new direction was akaruku, tanoshiku, hageshī puroresu – “bright, fun, and intense pro wrestling”. I explained the metaphor of “brightness” in my previous recap, used to express the clean booking approach in contrast to the opacity of Showa puroresu. Kekkigun’s prognosis wasn’t good, clearly being already seen as a relic of Showa puroresu. When the author went to interview Tenryu in Los Angeles that February, en route to his brief alliance with the Road Warriors, the topic of the faction didn’t even come up. On February 25 in Korakuen, Takano got a singles match against Tenryu. He lost, but he showed an uncharacteristic aggression, most notably manifesting in a piledriver spot on a table, that garnered praise. He continued to show promise in a six-man tag at Budokan on March 8, in which he wrestled alongside the Olympians against Tenryu & the Road Warriors. A March 27 Korakuen show saw Taue get his own singles match, and though he didn’t perform nearly as well there was still some small improvement. But by then, of course, Kekkigun was dead in spirit if not in name. On the March 8 Budokan show, Tiger Mask II received the final NWA World Heavyweight title match in AJPW history, against Ricky Steamboat. It wasn’t a great match, and the writing was on the wall even then about AJPW’s future collaborating with the NWA. That November, when Baba was asked during a university lecture why he had not booked Tsuruta or Tenryu to wrestle Steamboat for the belt, he claimed that the NWA had limited the number of challengers and vetoed the two. Of course, the more pertinent issue was the ACL tear that TM suffered during the match. He would spend the rest of the year on the shelf, as he decided in April to get knee surgery. Above: Mitsuharu Misawa recovers from knee surgery with his wife, Mayumi, and his daughter, Kaede. On June 5 at Budokan, Takano wrestled a singles match against Yatsu. He professed that “since Tiger Mask isn’t coming back, this match is very important [to Kekkigun]!” Alas, in 9:35 he took the pinfall to a Yatsu backdrop, having shown none of the fire he’d given Tenryu three months before. On June 7, at a press conference after the conclusion of the tour, Baba announced that Kekkigun was dissolved: “It’s rare that a year goes by and no progress has been made.” There was now another plan to display the youthful side of All Japan. But let’s get up to speed on Kobashi first. There had been speculation in 1988 that Kobashi would join Kekkigun, but despite how special Kobashi was considered by all as a symbol of a bright tomorrow, the hierarchical leap was just too great to make at that point. Kobashi dreamed of an American excursion, and repeatedly expressed his desire to Baba. As mentioned in the previous recap, Kobashi got a shot at Footloose’s All Asia tag titles in March, teaming with none other than Baba. That month, Tatsumi Kitahara began an excursion to Calgary, having been personally requested by the Dynamite Kid. While Baba had told Kobashi before that he would send him to Dory Funk Jr., Baba’s bridge with the NWA was burned just as Kobashi would have crossed it. He told Kobashi that “the time of America is over,” and that he would raise him. “Don’t talk about America anymore! Don’t say America anymore!” On May 16, at a show held in a parking lot, Kobashi got his first singles win against Mitch Snow. The Asunaro Cup (often translated as “Tomorrow League” in Western accounts) was the idea of Tarzan Yamamoto, who also came up with its name. Essentially, it was a successor to the Lou Thesz Cup of 1983, a midcard round-robin tournament between six younger talent. Three ex-Kekkigun members – Takano, Takagi, and Taue – and both members of Footloose were joined by a sixth man: Kobashi, who would make his first televised appearances through this tournament. In a July interview with Tenryu, the newly crowned Triple Crown Heavyweight champion opined that it had been best to disband Kekkigun, since he felt they played things too safe, and were “kind of like a friend’s club.” [2] He suggested that the other five men in the tournament “think about why Kobashi is in the league, [and] take a hard look at themselves.” The tournament began on July 1, the first date of the Summer Action Series. On the 8th, after winning his first tournament match against Fuyuki, Takagi was sidelined with a knee injury; he would not return until the RWTL tour. This gave everyone except Fuyuki a two-point freebie. On July 11, Kobashi would manage to wrestle Fuyuki to a time-limit draw (which G+ recently unearthed from the NTV archives), and on July 22, he got a countout victory against Takano, his first against a native wrestler. Kobashi wound up with five points, just one shy of the three-way tie between Kawada, Takano, and Fuyuki which would be handled in a three-match decision league. On July 25, Kawada won the Cup with a moonsault to Takano. The original plan was to give the winner a shot at the Triple Crown title (as would consistently be reported afterwards in the Observer), but Tenryu actually shot this down, and Kawada’s singles match against his faction leader would just be an untelevised (but fancammed, and really good) Korakuen match in October. Above: Kenta Kobashi takes the fall in his first televised main event, but he gets his first Weekly Pro cover photo in the process. Of the future Pillars, only Misawa had been a cover story to this point, and that was as Tiger Mask II. Elsewhere on this tour, Kobashi would wrestle his first televised main event, teaming with Jumbo against Tenryu & Hansen on July 15 in Korakuen. Before the match, Tenryu, the champion of the company, boasted that he would finish the match in ten minutes. It took him twenty. Ten days later, Baba remarked that “he had high hopes for [the finalists in the Asunaro Cup], […] but Kobashi is working the hardest”. Chapter 7 winds down with more insights behind the scenes. This is where Ichinose discloses that, beginning in the second half of 1988, he began to be included in what were essentially creative meetings with Baba. As a representative of the AJPW fanbase, when Yamamoto had suggested the idea that became the Asunaro Cup, Ichinose recalled to Baba how, as a schoolboy, he would plan his own round-robin tournaments in his notebook during boring classes. From here on out, Ichinose would write event cards with the advice of ring announcer Ryu Nakata to propose to Baba. Yamamoto envisioned a “macro-strategy” in which the company was determined to sell out Korakuen Hall and “develop a myth”. Ichinose, meanwhile, would focus on the provincial tours; while reporting at ringside, he would talk with Nakata about his ideas and opinions while listening to the customers around them. The “Korakuen myth” found its starting point in the January 25, 1989 match between the British Bulldogs and the Malenkos. While the four wrestlers did not have the size that Baba preferred in his wrestlers, and thus could not provide the “clash of big bodies” which Baba felt was the “true joy of wrestling”, Baba’s reluctant approval of the match was vindicated when it tore the house down. Subsequent Korakuen matches would develop the promotion's reputation for quality shows at the venue, such as beloved career undercarder Mitsuo Momota’s shots at the junior title, the aforementioned Baba/Kobashi vs. Footloose and Baba/Kimura vs. Olympians tag title matches, the Kawada/Kobashi opening match of the Asunaro Cup, and the July 15 Jumbo/Kobashi vs. Tenryu/Hansen main event. However, it appears that Ichinose fucked up or suffered miscommunication pertaining to the date of the Asunaro Cup final. There is no coverage of the moment when Kawada won the tournament, because Ichinose had falsely assumed that the tournament would end on July 28. He claims he would have flown to the show with a camera himself, but this was not possible because Ichinose was obligated to cover whether Antonio Inoki would win a seat in the impending House of Councilors election results. He recalls being chewed out by Yamamoto for his screwup, and refers to the Asunaro Cup as a bitter memory because of it.

-

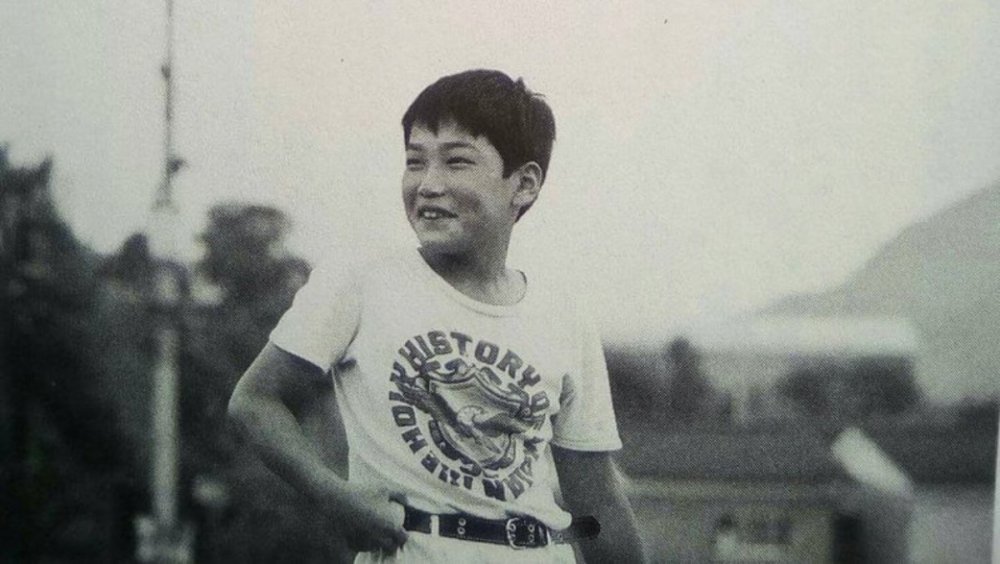

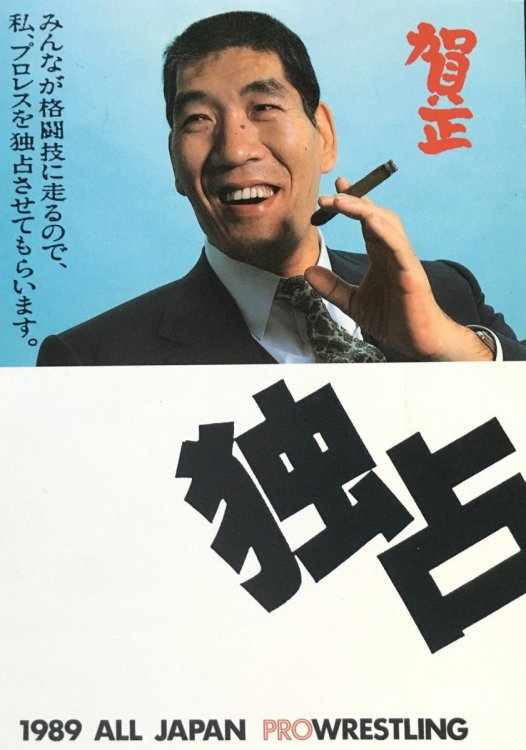

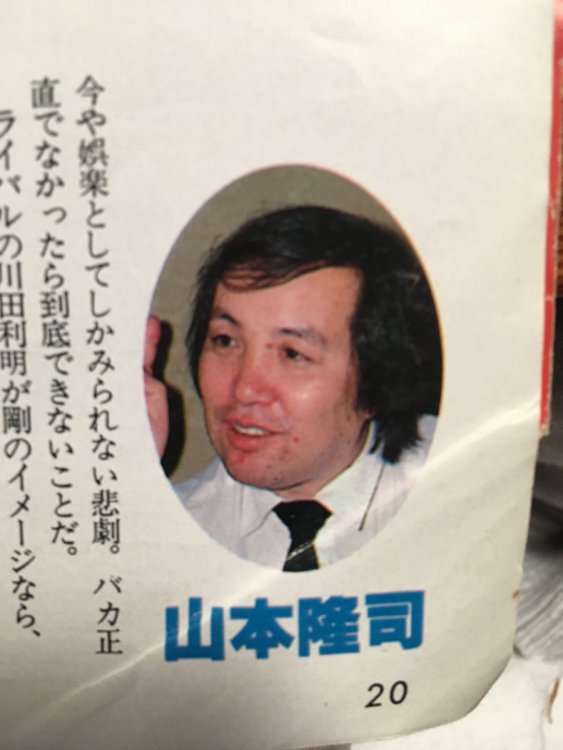

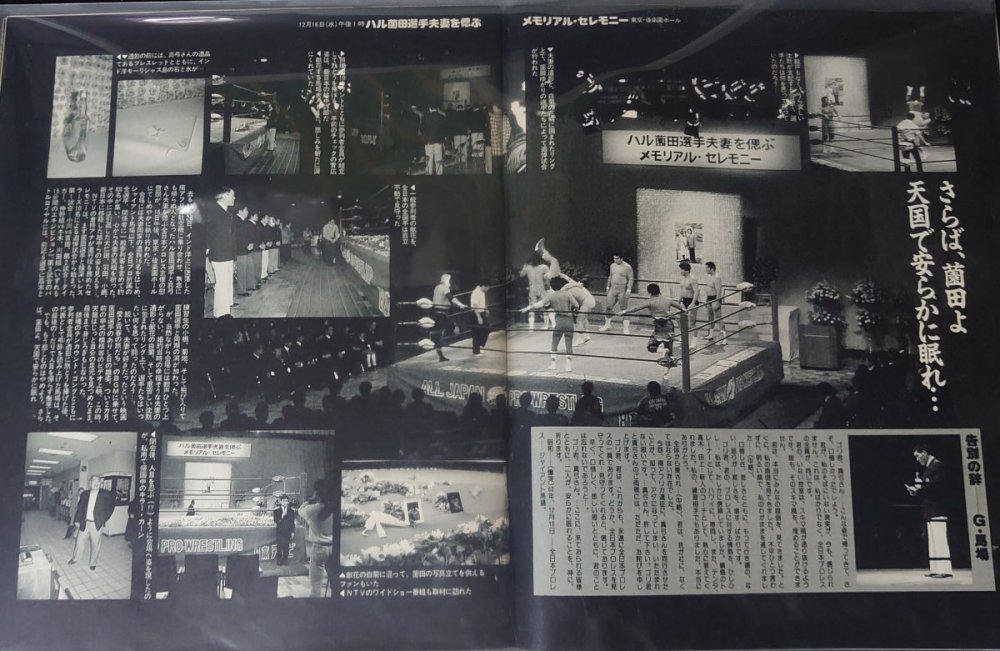

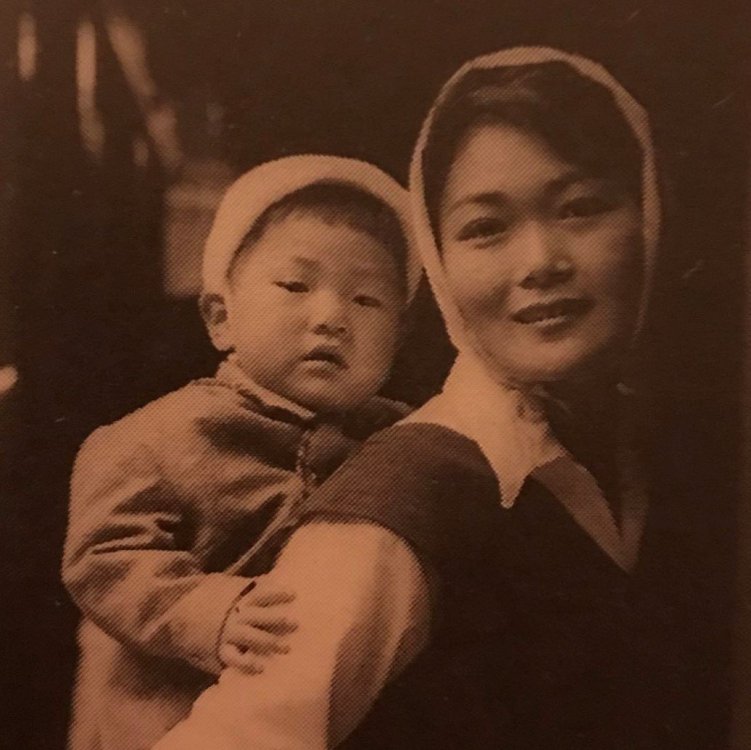

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 1-9, PART THREE Above: Kenta Kobashi, circa 1977. Chapter Four follows Kenta Kobashi’s path to pro wrestling. He was born and raised in Fukuchiyama. Like Kawada, the then fifth-grader’s interest in wrestling started with the August 25, 1977 Jumbo Tsuruta/Mil Mascaras match, which he watched on television with his older brother. Both brothers dreamed of becoming wrestlers, as they would playfight over a makeshift NWA title they had constructed out of cans. The following year, when his parents divorced, he and his brother moved with their mother to a different school district. While he was considering basketball (as well as volleyball) because Tsuruta had claimed in an interview that playing it had made him taller, Kobashi wound up joining the junior high judo club instead at the suggestion of a classmate who was looking for recruits, under the logic that direct martial arts experience would probably serve him better when looking for employment in wrestling. At some point during his junior high tenure, Kobashi attended an NJPW show, and he claims that he was struck by Stan Hansen’s bullrope for what wouldn’t be the last time. By this time AJPW had explicitly stated that they would only consider applicants with a high school education, so Kobashi had no qualms about entering. However, despite the offers of some private schools after he placed third in a judo competition, Kobashi entered the public school so as not to put financial strain on his mother, as his third-place performance would have only waived one-third of the tuition fee for the private institutions. To get into Fukuchiyama High School, though, he would have to place in the top 200 of the entrance exam, and on his first attempt he ranked a measly 658th. He took the advice of his homeroom teacher that “if you do not accumulate efforts day by day, you will not blossom”, and passed the bar on a subsequent attempt, though his eyesight deteriorated as a result. Kobashi thought he might switch to basketball or volleyball, but the judo club advisor gave an enthusiastic invitation, which he accepted. Unlike Misawa and Kawada with amateur wrestling, his achievements in judo at the high school level were relatively unremarkable. In his senior year, he placed third in the qualifying round at nationals, having been outweighed by his opponent in the semifinals by fifty kilograms. Upon graduation, Kobashi chose financial independence over wrestling because, once again, he did not wish to burden his mother. He took a factory job at a Yokaichi plant of Kyoto-based manufacturing company Kyocera. He had wanted to work in the General Affairs department, which he imagined was the “heart and soul” of the factory; unfortunately, he was given the tough work of cleaning the machines used to make copier parts. He recalls the dust being what made the job most difficult. Half a year into his new life, Kobashi found hope when he came across a newspaper article about Mike Tyson. Inspired by the young boxer’s success, Kobashi “wondered what his life’s purpose was”, and then realized it was wrestling. Kobashi would continue to work for Kyocera through the end of 1986, transferring to a plant in Kagoshima. This was to pay off the debts he owed for earning his driver’s license and vehicle. Then, he told his mother about his plan to quit and apply to become a wrestler. She did not like the decision, but she knew that he couldn’t change his mind once it was made, so she relented. It would fall to Kobashi’s brother to give him the encouragement he’d probably been seeking. The elder Kobashi had laid his own dream to rest, but he told Kenta that he was rooting for him from the bottom of his heart. Kobashi turned in his notice to Kyocera in 1987, and sent his resume to All Japan. Sadly, he was rejected. When Kobashi called the office, the person who picked up told him that he had no accomplishments. “Did you quit your job? Get a new job and work hard." He called again and again, but the answer never changed. And yet, still there was hope. Kobashi happened to be a customer of a gym owned by bodybuilder Mitsuo Endo, who had contacts in the wrestling business due to, among other things, his tenure as a referee for the International Wrestling Enterprise. He told Endo that, although he had already been rejected once, he really wanted to see if Endo could get his foot in the door of All Japan specifically. Kobashi would be willing to apply to New Japan if it didn’t work out, but he liked All Japan better. As he put it, while he admired Inoki’s strength, he “liked” Baba for his dignity and composure. In retrospect, Kobashi wonders aloud if he’d always looked to Baba as a father figure in a parasocial sense, before the two had ever met. Endo got his foot in the door. On May 26, 1987, All Japan held a show at the Shiga Prefectural Gymnasium in Otsu, and Kobashi was informed that an interview would be conducted there. When he arrived, the interviewer was revealed to be Baba himself. Kobashi expected the interview to go ahead, but before he could even talk to Baba, he was told by Shohei that he would be called when the tour was finished, but that he should say hello to everyone in the meantime, and move to Tokyo. Just like that, Kobashi was admitted. And yet, it seemed that Baba didn’t really care whether Kobashi was there or not. After the tour’s end, Kobashi was not in fact given a call, so he got fed up and called the office. Whoever picked up said “oh yeah, Baba-san told me about you. So why don’t you come?” In June, Kobashi moved to Tokyo, and then went to the AJPW office in Roppongi. As he entered, he was approached by reporters from Weekly Gong and Daily Sports (including future Jumbo biography author Kagehiro Osano), who requested that he take off his shirt and pose for photographs taken by a fellow reporter in the office. Kobashi was initially amazed that even a trainee would be given such attention by the press, but alas, this was a case of mistaken identity. Osano had mistaken Kobashi for Tamakirin: that is, Akira Taue. (In a 2020 interview translated by NOAH superfan Hisame, Kobashi recalls that he later asked if he could at least get one of the photographs that had been taken due to the misunderstanding, but they had long since been disposed of.) This incident and Baba’s apparent antipathy towards Kobashi are reflective of the regard, or lack thereof, in which he was held early on. Ichinose’s first memories of Kobashi date from the second half of the year where, as was customary for trainees, he would accompany wrestlers to the ring and then remain at ringside to spectate. He was just another new trainee as far as the reporter was concerned, but still the author recalls being struck by the intensity with which he observed the ring. However, near the end of the year, Kobashi would disappear from Ichinose’s view. On November 28, 1987, South African Airways Flight 295 was en route from Taipei to Johannesburg when it broke apart over the Indian Ocean, killing all 159 people on board. Two of these people were newlyweds Kazuharu & Mayumi Sonoda. Alongside Masanobu Fuchi and Atsushi Onita, Kazuharu was one of the “three crows” which had been the AJPW dojo’s first full products (as in, they didn’t go to Amarillo) in the seventies. He is perhaps best known to readers for his 1981-1985 stint as Magic Dragon, a sister gimmick to the Great Kabuki which spread to All Japan, but which was stripped from Sonoda in a mask vs hair match, as a sacrificial lamb to put over the “Mask Hunter”, Kuniaki Kobayashi, in his feud against Tiger Mask II. Sonoda had remained as an upper midcarder with occasional appearances on television (usually eating tag pinfalls), and was the head trainer of the dojo behind the scenes. He and Mayumi were on the plane at Baba’s suggestion, set to spend a honeymoon in South Africa as Sonoda did some work on shows promoted by Tiger Jeet Singh. Sonoda had taken this job after the Great Kabuki, Ashura Hara, and Takashi Ishikawa had all turned it down. As the Japanese press pursued Baba for comment, the Great Kabuki decided that his valet Isao Takagi needed to be replaced for poor performance. Without consulting Baba, he asked Kobashi if he was already serving this function for another, then assigned him to Baba. When Baba returned to the hotel, Kobashi told him he was to be his new valet. The uninformed and grief-stricken Baba angrily rejected Kobashi, telling him to “go back to Fukuchiyama”, under the impression that Takagi had used the trainee so he could skimp on his duties. Kobashi felt that he could not reveal Kabuki’s involvement, because it would sound like he was tattling on him. The two would not speak for the next two months, but Kobashi continued to perform as Baba’s valet in silence. He was also saddled with the laundry of senior wrestlers, and since coin-operated laundries were not as common back then, Kenta often had to wash their clothes by hand. Kobashi and Ichinose both believe that Baba’s treatment was a test of the young man’s fortitude; the man himself compares it to that stock scene in Japanese period drama wherein a samurai patiently sits before a gate, waiting to be allowed inside. Kobashi would make his unofficial debut in the meantime, though. On December 16, five days after the Real World Tag League final, a memorial ceremony for Sonoda was held at Korakuen Hall. [1] During this event, three matches were booked, ending with a ten-man battle royal. Here, Kobashi and Tsuyoshi Kikuchi made their first public appearances between the ropes. Above: A spread of coverage of the Haru Sonoda memorial show, on which Kobashi made his informal debut. On February 26 in Ritto, Kobashi made his proper debut. In the second match on the card, he wrestled Motoshi Okuma, who had dominated the All Asia tag title division in the late Seventies alongside the Great Kojika, but after television appearances as a jobber to the stars in the mid-80s had wound down into an undercard role. Kobashi was pinned in 4:48 after a diving headbutt, but as he went backstage, Baba told him that a surprise was waiting for him at the hotel, and finally invited him to dinner, from which he had been snubbed as a trainee. As Kobashi recalls, all of the hardship and distress he had weathered was washed away in an instant. From this day forward, Baba would demand that Kobashi always be an ebisco, a term for “glutton” used in sumo. Kobashi would not get to work the first Budokan show after his debut, which was the second card of the Champion Carnival tour. AJPW had an odd-numbered roster at that point, and he and Kikuchi alternated opening matches against Mitsuo Momota in the first five dates of the tour. Not long after this, however, Kobashi would become an “indispensible part” of the company. One of Weekly Pro’s recurring features at the time was a page titled Chūmoku! Kono ichiban (“Attention! This first”), in which ringside reporters spotlighted young talent in undercard matches. Ichinose had been assigned to the All Japan beat since the ban of 1986, but Chūmoku! Kono ichiban had remained “a remote page” to the journalist, who recalled being frustrated by how the promotion’s bland undercards made him feel that he was being denied the right to do his job. Not since the era of 1982-3, which had seen the likes of Mitsuharu Misawa, Shiro Koshinaka, and Tarzan Goto blossom under the guidance of Akio Sato, had All Japan displayed any of the underneath vitality which made NJPW and the UWF so stimulating. When Ichinose had been covering the company, even the “new” guys weren’t really new, but ex-sumo guys; John Tenta was almost 24 when he debuted, and Takagi and Taue were both two years his senior. But then, on April 9, Ichinose was in attendance for the thirteenth show of the Carnival tour in Kumamoto. In the third match on the card, for the first of many times (not counting the Sonoda memorial battle royal, in which both had worked), Kobashi would wrestle Toshiaki Kawada, who at that time was exactly one month deep into his first All Asia tag title reign as one-half of Footloose. Kobashi would lose to a lariat in 7:46, but his performance finally put Ichinose on the page which had long eluded him. On the April 26 issue of Weekly Pro, the entire Chūmoku! page was devoted to this match. Ichinose’s recollection of how Kobashi was so refreshing for the company, whether or not he was earmarked to reach the top, does much to contextualize his 1989 Newcomer of the Year award from Tokyo Sports. Yes, these are mark awards, but this still feels reflective of how wrestling journalists were endeared to him. [2022.11.05 ADDITION: I also believe that Kobashi's early acclaim from wrestling journalists was far more important to his trajectory than his losing streak. This has long been credited in the West as a brilliant plan to get him over, but a young wrestler losing a year of matches before their first win had not been unique in Japan before. Kawada didn't win a singles match until 14 months after his debut, and there are JWA-era cases that went winless for even longer. It was the attention Kobashi earned that made that loss streak special. This was not unique to him either, as the likes of Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki got ample early coverage in Weekly Pro.] One year later, Kobashi received his first title shot. At Korakuen Hall on March 27, 1989, he challenged Footloose for their All Asia tag titles with none other than Baba as his partner. Footage has sadly not surfaced, as this show did not receive a television taping, but the result I found was that Kawada pinned Kobashi with a dragon suplex in 18:07. Ichinose calls this match, alongside Baba & Rusher Kimura’s February 25 shot at the Olympians’ AJPW World Tag Team titles, the birth of the “New Baba”. We transition into Chapter Five, which gives us some insights into the AJPW reform plan developed with the collaboration of Weekly Pro editor Tarzan Yamamoto. --- Above: The “dokusen poster”, released in January 1989, is emblematic of the image strategy which ushered in this new era of All Japan Pro Wrestling. In the top half, Baba smiles with a cigar in hand, with text on his right that roughly translates to: “Since everyone else is getting into martial arts, I’m going to monopolize pro wrestling.” Red text to Baba’s left reads “happy new year”. On the bottom half, the two-character word dokusen (“monopoly”) is written in giant boldface. Tarzan Yamamoto was assigned editor-in-chief of Weekly Pro Wrestling after Hideo Sugiyama’s transfer to sister publication Martial Arts News. The AJPW ban had been lifted for five months, and with the return of much of Japan Pro Wrestling to NJPW, Yamamoto felt a dangerous imbalance of power in the wrestling world. Knowing that he wouldn’t be able to get an interview with Choshu anyway, Yamamoto approached Baba for one, which was granted. In the April 27 issue of Weekly Pro, Baba spoke honestly about his feelings in the wake of Choshu and company’s U-turn back home. “Two years ago, when Choshu and his friends wanted to come to All-Japan, I accepted. When I accepted them, I cleared up all the problems and made sure that they would not complain. So I told them to do the same. I'm not trying to take their lives. There's nothing in the contract about taking lives.” All Japan was resuscitated by the start of the Tenryu Revolution that June, with former tag partners Jumbo Tsuruta and Genichiro Tenryu now embroiled in a feud. But there were still deeper problems beneath. The first Jumbo/Tenryu singles match of the feud had drawn well, bringing 12,100 to the Nippon Budokan. However, despite the October rematch in the same venue having an announced attendance only 300 below, fans in the second floor could be seen lying down across multiple seats as if on a couch. When the first Triple Crown unification match was booked six months later, between Tenryu and Bruiser Brody, old tendencies won out and the match ended in a double countout at thirty minutes. Ichinose was at ringside, and “was just frustrated”. It was now mid-1988. At what I am guessing was a press conference after the end of the Super Power Series tour, Baba displayed the major matches of the following tour for reporters, before offhandedly asking that they let him know if they had any good ideas. Most did not respond, but Tarzan, who recognized that the company still had major problems, could be heard saying “alright”. This wasn’t the first time that Baba had asked for ideas. Four years earlier, around the same time of year, he was drinking tea with Gong editor-in-chief Kosuke Takeuchi and NJPW president/future JPW head Naoki Otsuka at the Capitol Tokyu Hotel in Akasaka. When Baba spoke of his desire to somehow sign Satoru Sayama to get Tiger Mask, Takeuchi was the one who pointed out to him that his best bet was to get Ikki Kajiwara’s blessing to just make a new Tiger Mask. [2] [2022.11.05 ADDITION: In the early years of All Japan, Baba was helped by Monthly Pro editorial advisor Satoshi Morioka, who was indirectly involved in Jumbo Tsuruta's courtship and is credited with pitching the 1975 Open League.] Once again, Baba would have a meeting at the Capitol Tokyu Hotel. Yamamoto was accompanied by illustrator colleagues Shiro Sarashina and Haruo Matsumoto. Over six hours, the four men analyzed the current state of AJPW and brainstormed how to change the promotion’s image. Sarashina made an unflattering comparison of the company to the baseball team the Lotte Orions, whose spectators in Kawasaki Stadium often entertained themselves by playing catch and mahjong. Nobody was throwing balls in Budokan at least, but the sluggish attendance and atmosphere made it a fair comparison. The “dokusen poster” at the head of this section is representative of the fruit of this meeting. All Japan would not be seduced by martial arts, be that the shoot-style of the now-Newborn UWF or NJPW’s contemporaneous work with Soviet amateur wrestlers. However, the pro wrestling that Baba sought to monopolize was itself different. It was to be a “bright” wrestling whose fundamental sportsmanship did away with the opacity of so much of Showa puroresu. In July issues of Weekly Pro, Baba espoused his ideals of sportsmanship, and stated a belief that the “restoration of trust in professional wrestling” was the only way to earn the support of the modern fan. Ichinose does not try to suggest that Yamamoto had any direct influence on what would later be called oudou/”King’s Road” (in fact, Ichinose hasn’t used that term yet, so I hope that he will get to its origin later in the book). However, he also admits that any speculation on his part that Baba had always had reservations about being a star in an era of wrestling that was far from his idea of sport is just that. However, there was one point before 1988 where Baba had clearly expressed his sensibilities. On March 13, 1986, Jumbo Tsuruta wrestled Animal Hamaguchi as part of a one-night best-of-5 series between AJPW and JPW wrestlers. Baba was moved by the grace with which Hamaguchi accepted his defeat, and commented to the press that he wanted all of the others to learn from him. This would not stick, however, and even the third Jumbo/Tenryu match of October 1988 paid such ideals no mind with its DQ finish.

-

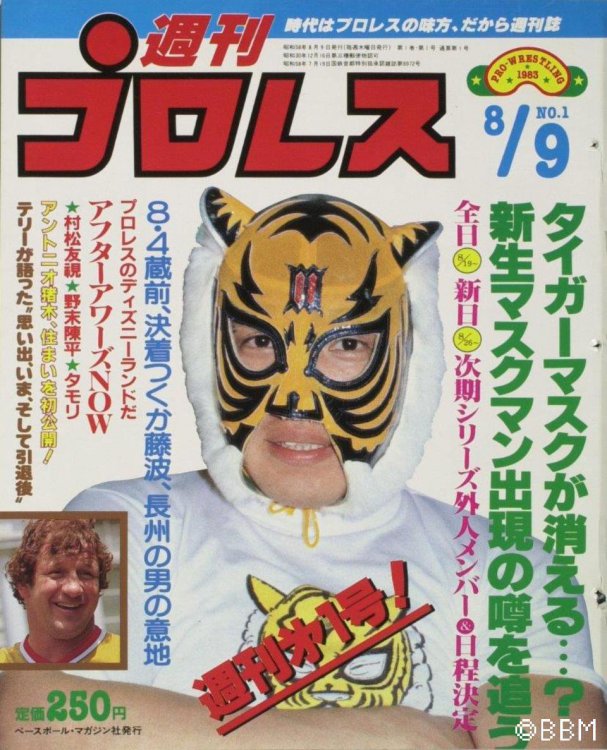

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 1-9, PART TWO Chapters 2-3 were 16 and 12 pages, respectively, so I decided to transcribe and cover them together. 4-5 are of similar length, so I will probably combine them as well. ---- Chapter Two starts by talking about the UWF. Initially I was annoyed at what seemed like a drawn-out digression (this is not to disparage the book’s craft – it was not meant to be consumed the way that I, an illiterate, am doing), but when I quickly realized where it was going this became fascinating. This chapter is a snapshot of puro journalism politics in the 1980s, specifically the tensions between Weekly Pro Wrestling and AJPW(+JPW) in the period before Takashi "Tarzan" Yamamoto became editor-in-chief, a position from which he would ingratiate himself to Baba and become an important creative consultant. From the photos in the book I can tell that it’s going to take 500+ pages to get to the actual Shitenno/Gotsuyo era of 1993-, but a digression like this at least promises some interesting context along the way. Monthly Pro Wrestling, a magazine published by BASEBALL MAGAZINE SHA Co., Ltd (henceforth abbreviated as BBM) whose history went back to the mid-1950s, rebranded as Weekly Pro Wrestling in 1983. I don’t know if his tenure extended before the rebrand, but Weekly Pro’s first editor-in-chief was Hideo Sugiyama, a position he also held for sister BBM magazine Martial Arts News. [2021.07.26 correction: this post implied he was pulling double duty, but he actually switched to running Martial Arts News after handing the Weekly Pro chair off to Tarzan Yamamoto in April 1987.] In his coverage of the circumstances behind Tarzan Yamamoto’s step down from editor-in-chief, Dave Meltzer wrote that Yamamoto was credited with “bringing mainstream coverage of pro wrestling in Japan from the Apter-mag level almost to Observer level” (Wrestling Observer Newsletter, July 8, 1996). (The term Tarzan would coin for the style of coverage that Weekly Pro provided was “print wrestling”. [1]) This should not be taken to mean just his EIC tenure, though, as this section establishes that even during Sugiyama’s tenure – during which Yamamoto was head of the editorial team – the magazine was much bolder than that Apter mag comparison would indicate. As author Hidetoshi Ichinose notes, in some respects Weekly Pro was like the UWF itself, in that it “rejected traditional wrestling and created new values”. Sugiyama “did not listen to the logic of the old industry, but the voice of fans who had nowhere else to go, swirling around venues all over Japan. ‘Let me find out who’s the strongest! Let me see who’s the strongest!’” (The riot at the Kuramae Kokugikan in the aftermath of the Inoki/Hogan IWGP match and Choshu angle on 1984.06.14 is presented as a manifestation of the discontent of this shifting fanbase.) In his 2017 book 1984年のUWF (“UWF in 1984”) as cited by Japanese Wikipedia, Ken Yanagisawa accuses Sugiyama of deceiving his readership into thinking the UWF was legit to boost sales. This is how you shift the culture of wrestling fandom. This is how you get Korakuen pelting garbage into the ring when Jumbo vs. Hansen (1989.04.16) has a fuck finish. This is how you make King’s Road not only a feasible creative direction, but perhaps a necessary one. Weekly Pro’s first issue, for the week of August 9, 1983, sent a message from the jump. Despite Terry Funk’s retirement tour, he was only given a square of real estate on a cover which primarily featured Tiger Mask. Sugiyama’s reasoning was that Tiger Mask could change professional wrestling from a “world of fans” to “a universal world”. The age of B-I Cannon was over; the future was now. Things get really interesting in early 1986. In the wake of the NJPW/UWF angle, New Japan got the Weekly Pro cover for the first six issues. At or around the time the 2/25 issue (released the second week of the month) hit shelves, BBM president Tsuneo Ikeda received a letter signed by Giant Baba and Riki Choshu. This letter alleged unfair coverage, and declared a boycott of the publication. Ichinose claims that this was unreasonable and that the coverage was not so disproportionate; in 1985, NJPW got 21 cover stories, AJPW got 18, and the UWF got 6. In response, Weekly Pro adopted guerilla tactics to report on them. Reporters and photographers bought tickets to provide ringside coverage (the author, who was in his early twenties at the time, started reporting on AJPW in this capacity). When necessary, photos of the ringside area and waiting room were provided by Weekly Fight magazine. Ichinose notes that this strategy was met with “silent approval”, and that he believes that AJPW were thus not primarily responsible for the boycott. Choshu’s animosity towards the wrestling press was so pronounced that an entire subsection of his Japanese Wikipedia page is devoted to it, so I’m inclined to guess that this indeed was his doing. Ichinose remarks that the battle between Choshu and Yamamoto, the only Weekly Pro reporter who had been banned before the magazine as a whole had been, would continue for many years. The boycott was lifted after seven months, but Weekly Pro were still not allowed to send ringside photographers to the 1986.11.01 event, where Hiroshi Wajima would be making his professional wrestling debut against Tiger Jeet Singh. Weekly Pro had to make this the cover story, though, so they settled for a shot taken from the second row. The last few pages of the chapter are about Kawada’s miserable excursion and return. By the time he came to San Antonio, Chavo wasn’t there. As you may know, the Kawada/Fuyuki team started here. However, when visa issues forced Fuyuki to return home, Kawada was fired as there was no use for him in a singles capacity. Kawada called Akio Sato, who told him to go to Calgary. There, he finally got experience as a singles worker, and wrestled under a mask for the first time as Black Mephisto, on a meager $200 a week. Stampede wanted Kawada to play a Shogun Wakamatsu-style heel, but Kawada couldn’t do expressions as a masked performer, so he just “barked viciously”. After being sacked there, Kawada went to Montreal on Sato’s direction. Here, he performed in a high-flying style which got him praise in some corners but also had a ceiling at that time. Kawada’s excursion ended abruptly when visa issues forced him to return home. When he arrived, it was as if he’d never left. Once again, he didn’t even get his own name stamp for the tour pamphlets. The makeshift one just read “Kawada”, likely a composite of the “川” on Takashi Ishikawa’s stamp and the “田” on Jumbo Tsuruta’s. The chapter ends recapping 1987 up to August 21, when Kawada finally made his move in an angle which saw him join Revolution. --------- Chapter Three is about Taue. Taue seems to have come from the poorest family of the Pillars. Like, “roast a snake in soy sauce for dinner" poor. He recalls carrying salt and miso paste in his pockets when playing outside after school, to season the cucumbers and turnips that neighbors would give to him. Taue was a mischievous kid. He recalls playing hide-and-seek in elementary school and climbing into the ceiling, only to fall through a panel into a classroom. Once, he accidentally set a shrine on fire playing with firecrackers. During his junior year in high school, he recalls knocking out the leader of a gang of delinquents with a headbutt, after which the guy got 12 of his friends to come beat him up. Taue didn’t back down, and broke the leader’s collarbone. Taue reached 1st dan in judo, but didn’t actually like fighting that much. His athletic dreams laid in baseball for much of his youth, although he also did long jump and shot out in junior high. He joined his high school baseball team, but they were far from the national level. Despite the suggestion of the advisor of his high school sumo club, he was very resistant to the idea of wearing a mawashi. However, when his dream of being a collegiate athlete was dashed by his lackluster academic performance and his poverty, Taue went into sumo. He did so partially to make his sumo-loving momma Mitsuko proud after having been such a punk kid. He joined the Oshigawa stable, headed by Oshigawa Oyakata, whose training camps he had already attended during high school. Long story short, he was promising, and had a considerable amount of natural athletic ability. However, it appears that he retired as a response to the abusive culture. Taue claims that Oshigawa would strike him with his shinai (wooden sword), hurting him to the point that he could not perform well, and then complain when he lost. Taue was at a crossroads. He was already married, so he had to find work somewhere. He considered driving a truck until ragoku comedian Yasumichi Ai (now known by his stage name San'yūtei Enraku VI), a friend of Genichiro Tenryu’s from junior high, suggested that he enter professional wrestling. As I covered before in this thread, Taue was initially signed through JPW. It was essentially a paper organization at this point, but it cushioned the appearance of the signing in the eyes of the sumo association, which was already tense with AJPW after the signings of Isao Takagi, John Tenta, and especially Hiroshi Wajima. (As I have earlier noted, this kind of political game wasn’t even new to AJPW. In the late 70s, Takashi Ishikawa originally worked as a freelancer after All Japan had recruited Tenryu and Tonga.) Baba would later write that an old reporter was critical of Taue’s build and slowness, making an unflattering comparison to Umanosuke Ueda. However, Baba saw that he had better spring and flexibility than Ueda, and really believed in him as a potential late-blooming major talent. Of course, he was also attracted to Taue’s 190cm height. “What is the best part of pro wrestling? There are many wrestlers in the world who are as big as Choshu. The appeal of professional wrestling is that when big bodies collide and splash each other, the power of the collision attracts the audience. In short, professional wrestling is about doing things that ordinary people cannot do. In our case, it would be Tenta, Jumbo (Tsuruta), Tenryu and Yatsu. That kind of power has been the selling point of All Japan. New Japan probably doesn't have it.” [2] The chapter basically ends with the formation of Kekkigun – Taue, Tiger Mask, Shunji Takano, Isao Takagi, Shinichi Nakano – the (ultimately short-lived) proto-Super Generation Army faction of young guys who sought to overtake Revolution. --- From titles, it looks like Chapter 4 will be about Kobashi, and Chapter 5 will be about Tarzan Yamamoto’s reform proposal that saw him become a creative consultant to Baba in the wake of JPW’s return to NJPW.

-