-

Posts

422 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Everything posted by KinchStalker

-

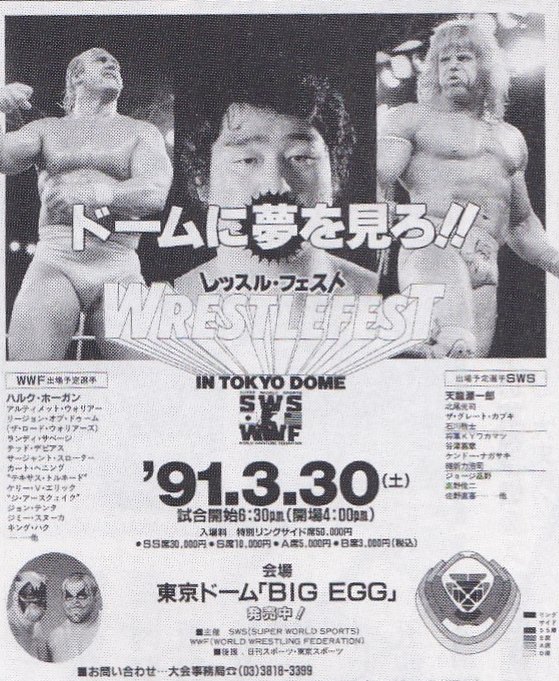

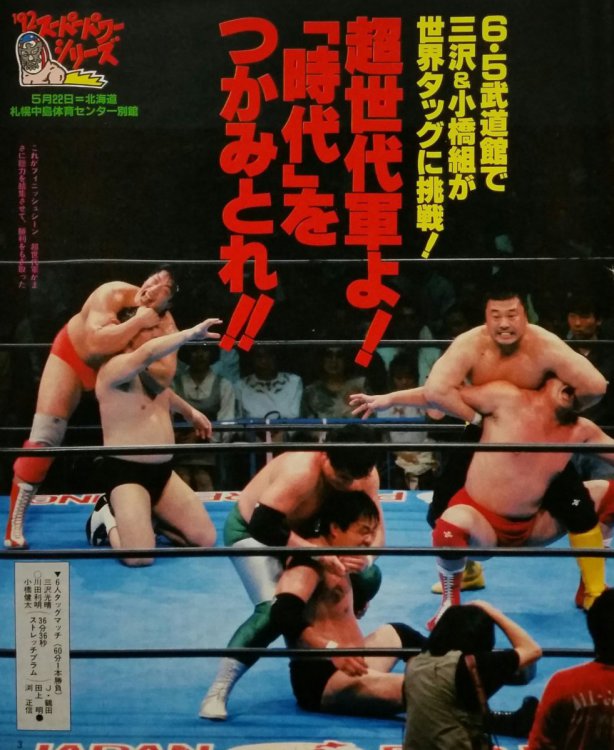

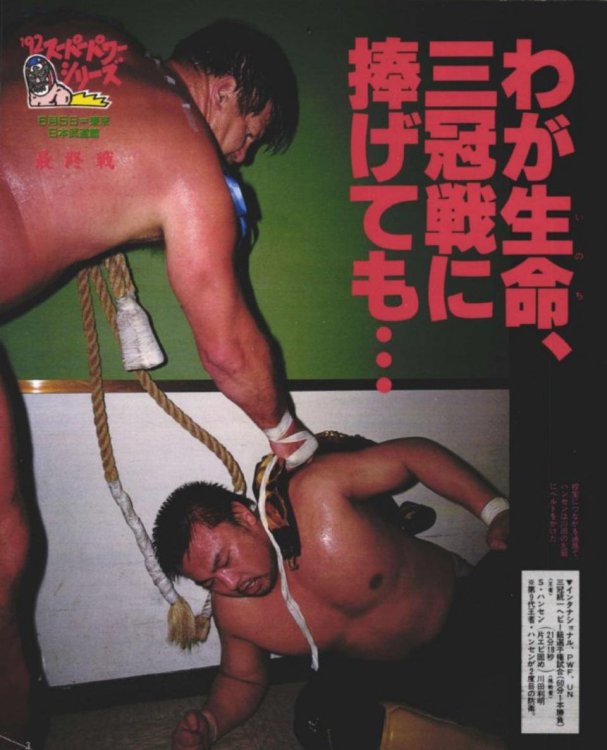

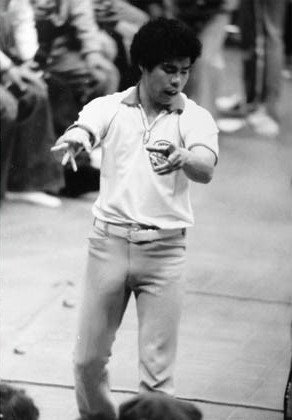

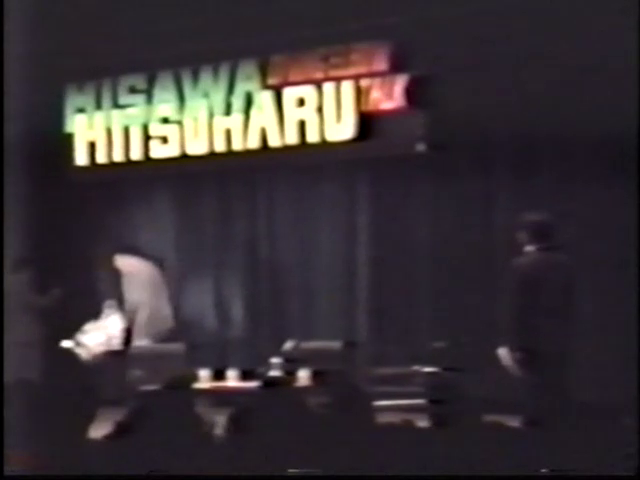

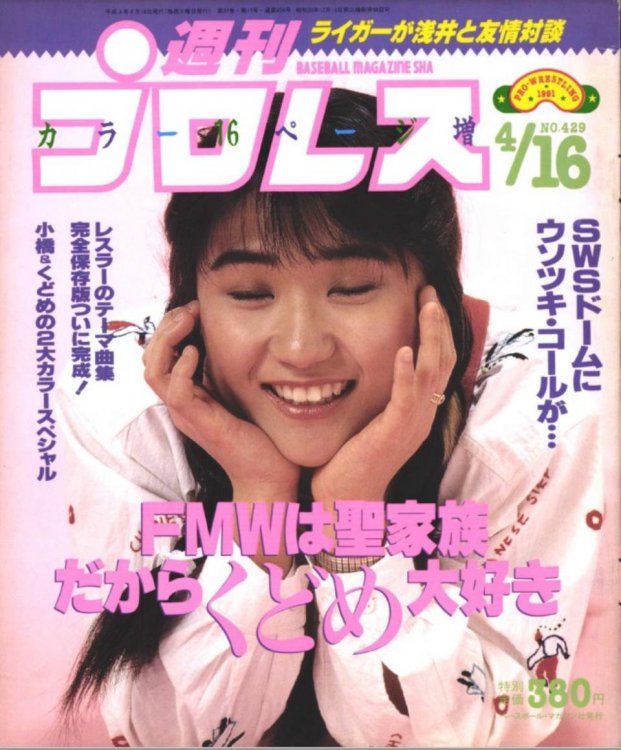

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 18-21, PART THREE (THE NIGHT THE PILLARS WERE BUILT) With nearly two million residents as of a 2020 census, Sapporo is Japan’s largest city north of Tokyo, and is the political, cultural, and economic center of Hokkaido, the northernmost of the Japanese archipelago’s five main islands. It became the first Asian host of the Winter Olympics in 1972 (and would have been so 32 years earlier, had the second Sino-Japanese War not forced them to relinquish the hosting rights to an event that never happened anyway). It was the first city that my hometown of Portland, Oregon established a sister city relationship with. It holds an annual snow festival. Sapporo has been familiar to puroresu since 1954, when the nascent JWA booked a three-night run that August. It’s seen its share of big shows and title matches in the decades since, from the Sharpe brothers winning the NWA World tag titles back from Rikidozan & Kokichi Endo in 1956 to NJPW’s two-night Summer Struggle just a few months before I wrote this. But like most cities in the world, it isn’t Tokyo, and building a loyal audience in a large but ultimately regional city is a difficult matter. In the summer of 1985, Masahito Hino opened what seems to have been a wrestling merch store in Sapporo called Ring Palace. He was to be the promoter of a UWF show at the Sapporo Nakajima Sports Center. This, however, put him in the crosshairs of the AJPW sales department, who harassed him for arranging an event to be held just one night before All Japan’s stop in Sapporo. It was a moot point, as it turns out. The show was set for November 25; the UWF’s final show would be on September 11. Almost three years later, the Newborn UWF selected Sapporo to host their second event. UWF Starting Over would draw 5,200 to the Nakajima Sports Center.1 One week earlier, All Japan had run the same building with a show headlined by Revolution and the Olympians duking it out for the just-unified AJPW World tag titles. They had drawn 4,400. AJPW wouldn’t work Sapporo again until the following July. Before a show that saw Tenryu & Hansen beat the Olympians for the tag titles, Baba held a talk event where he spoke directly to the crowd for two hours. Hino recalls how this gesture reflected an All Japan that sought to form a more direct audience with its fans, and by extension sought to puncture the atmosphere around professional wrestling that had made mens’ puroresu less approachable for women and children. They drew 3,800 that night, which was fifty more than NJPW had drawn two weeks earlier. According to Hino, while good matches had been held in Sapporo over the years, the impression that it wouldn’t hold great matches had prevailed; he recalls when an announced singles match between Akira Maeda and Bruiser Brody was cancelled, and notwithstanding the general opinion on Brody in these circles, that’s the kind of cancellation that can hurt a market. Meanwhile, AJPW would make incremental progress in the market by holding infrequent but consistent events. UWF’s Fighting Art show on October 25 was the top-drawing Sapporo show of 1989, but when AJPW returned for a televised date in that year’s RWTL, they drew a thousand more than they had last time. Those 4,800 certainly made the right call, as they were the first Japanese audience in a quarter-century to watch Giant Baba get pinned by a native wrestler, in a great, subversive match. It would be six years until AJPW drew under 5,000 again. The Nakajima Sports Center held four wrestling shows in 1990. NJPW was first, putting on a January 25 show headlined by a Vader/Chono singles match; they drew 3,860. AJPW returned on the 1st of June, as 5,250 came to a show headlined by a Jumbo/Kabuki vs. Misawa/Kobashi tag. A third and final UWF show in the Center came the following month, and 5,600 came to see Maeda/Fujiwara and Takada/Yamazaki matches. Finally, AJPW came back for a RWTL date on December 1. This show featured the second-ever Misawa-Kawada/Miracle Violence Connection match, as well as a novel six-man which saw the Funks team up with Andre the Giant to wrestle Stan Hansen, Danny Spivey & Joel Deaton. The show was quite likely dampened by the broken leg which had hospitalized Baba the previous night, but All Japan’s consistency in Sapporo was rewarded by an attendance of 6,100. Hino speculates that the dissolution of Newborn UWF might have helped AJPW’s Sapporo audience grow, though I’m skeptical that this was a significant factor; all three of its splinter promotions held Sapporo shows in 1991 and drew about 5,000 each. But despite NJPW drawing 6,350 on a July show headlined by Vader/Hashimoto, AJPW would draw the largest crowd of the year yet again, with a November 29 show headlined by the Misawa-Kawada/ Tsuruta-Taue RWTL match bringing 6,600 through the doors. On May 22, 1992, the three top members of Chosedaigun all made their Tsurutagun counterparts submit in a Sapporo six-man. [The formatting and font gives this away as a Weekly Pro page, but I cannot confirm the source issue.] Five months after All Japan’s previous stop in Sapporo, they would outdo themselves. The Chosedaigun/Tsurutagun six-man of 4/20/91 was already legendary, and the city was privileged to hold a rematch on May 22. A whopping 7,800 came to see yet another early-90s AJPW classic. Their annual RWTL stop on November 27 drew 6,450, with a show headlined by the Misawa-Kawada/Baba-Kobashi tournament match. Emboldened by three years of strong attendance, AJPW booked the Nakajima Sports Center for two consecutive nights: May 20-21, 1993. --- The 1993 Super Power Series tour would begin in Korakuen on May 14, but there would be a preamble. Weekly Pro Wrestling parent company Baseball Magazine (BBM) had purchased Korakuen shows from NJPW in 1986 and 1993, but this would be their first AJPW show. While he was “in charge” of the event, Ichinose was not there to cover it; he had been pulling double duty since the formation of JWP (which would lead to a commentary job on their WOWOW program), and was accompanying them on a trip to Saipan. Due to the special circumstances, Kawada’s first match against the Super Generation Army was not alongside Taue; rather, he wrestled Kikuchi in the semi-main, winning with a stretch plum. When the tour began, though, so did Seikigun (the Holy Demon Army).2 Debuting with a victory over Misawa & Kikuchi, Kawada & Taue symbolized their equality on this tour by alternating which member entered first and whose name was called first, night by night, on top of their entrance theme mashup. The latter had been seen in the Hansen/Brody and KakuRyu teams, but the alternating name order was novel, even if “Kawada & Taue” was always how the team was referred to by fandom and the like. The two Sapporo shows were dates 6-7 of the tour. AJPW would not beat the previous year’s attendance record, but they had not expected to. The first night would draw 6,100, and the second 6,400. According to Hino, 1,000 of those tickets were sold on the day/s of, and about 10% of the total attendance had bought their tickets at his shop. On the first night, Kawada & Taue defeated the Miracle Violence Connection to end the final AJPW World Tag Team title reign of what had been the definitive foreign team of the early decade in the promotion. Misawa & Kobashi, meanwhile, beat Hansen & Spivey in the semi-main. The second night was even more significant. After the Can-Am Express lost an All Asia #1 Contendership match against the Patriot & the Eagle the previous night, Dan Kroffat made up for it by defeating Fuchi for the junior title, and thus ending what will quite likely always be the final 1000+-day title reign in puroresu. Even this, though, would pale in significance compared to what followed. Photos from the four singles matches that built the legend of the Four Pillars. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #555, dated June 8, 1993 (photograph included in free preview of the issue’s archived digital copy)] Mitsuharu Misawa, Toshiaki Kawada, Kenta Kobashi, and Akira Taue all wrestled singles matches against the four top All Japan gaikokujin of the early 90s. All four would win. Taue was first, wrestling Danny Spivey in the first of three matches officiated by Kyohei Wada. Taue suffered a laceration under his left eyebrow, but he hit the nodowa otoshi to win his first singles match against Spivey, after four attempts. Next up was Kobashi, wrestling a former Triple Crown champion in Terry Gordy. Kobashi had already pinned Spivey on February 28, but had not beaten Gordy, just as Taue had beaten Gordy in a 1993 Champion Carnival match, but not Spivey. In just over nineteen minutes, he changed that. After a Baba-style neckbreaker drop didn’t do the trick, a moonsault did. A detail Ichinose notes is Kobashi’s clenched fist in the postmatch, which he appears not to notice at first. The fist pump before a moonsault was already a Kobashi trope by this point, and much later on, the so-called ‘Fist of Youth” would become part of Kobashi’s brand in another sense; just from looking at his social media (seriously, he ends like 40% of his tweets with 『いくぞー』!!) you can tell that he uses the gesture in his motivational speaking. Kobashi bowed to all four sides of the Nakajima Sports Center, and when he returned to the waiting room, he took questions from reporters and shook hands with all of them. Ichinose only gives Kawada and Misawa’s matches against Steve Williams and Stan Hansen a cursory mention, but the latter was Misawa’s third successful Triple Crown defense, coming off of his loss to Hansen in the previous month’s Carnival final. Above: Misawa at the 1988 wedding of Tokyo Sports reporter Soichi Shibata (right). Five years later, Shibata would be the first journalist to refer to Misawa, Kawada, Kobashi and Taue as the Shitenno (“Four Heavenly Kings/Four Pillars”). [This photograph was shared by Shibata himself on Twitter on the day of NOAH's 2021 Misawa tribute show.] After getting his law degree in 1982, Soichi Shibata became a reporter for Tokyo Sports. He worked for the publication for three decades until his 2015 retirement, and he has been mentioned earlier in these recaps. However, a Western puroresu fan is most likely to recognize him for over a quarter-century of commentary work for NJPW, which ended on the first night of Wrestle Kingdom 15 in 2021.3 Shibata was the first one to refer to Misawa, Kawada, Kobashi & Taue as Zen Nihon Shitenno, and he did so in his report on the May 21 show. Not every name thought up by a puroresu journalist took root, but some did. Ichinose claims credit for coining “Doctor Bomb” to name Steve Williams’ spinning powerbomb. When Taue began doing a chokeslam off the apron, the name he had come up with was “Nabiki Nodowa Otoshi”, but Weekly Gong’s name “Cliff Nodowa” was the one that stuck with fans. I need to get something out of the way now; shitenno is not a distinct term. It is a standard Buddhist cultural reference that had been invoked before in puroresu, and has been since. Trying to look deeper into the symbolism of the Four Heavenly Kings to see parallels to Misawa, Kawada, Kobashi & Taue, or perhaps even holding onto the term Four Pillars as hard as we in the West do (I’m thinking of OJ’s annoyance with the term, which he expressed in one of the GWE threads), would be a bit like Japanese fans of Western wrestling trying to determine which of the Four Horsemen were Pestilence, War, Famine and Death. In fact, the four men that the Pillars beat on that second night in Sapporo had themselves been called the foreign Shitenno of the period. And grumbling about whether Akiyama “deserved” to be a Pillar more than Taue is particularly silly; from what I understand, after Jun got his main-event push,the term gotsuyo (五強, “Five Strengths”) emerged, which is another Buddhist reference. Just because it’s a standard cultural reference, though, doesn’t mean that it didn’t take root in the domestic fandom, or that AJPW didn’t immediately run with it. In Misawa & Kawada's first Budokan main event as enemies, the Holy Demon Army double-teams the Triple Crown champion. "From the legend of Sapporo to the myth of Budokan. Four young people look at their dreams, embrace the future, and fight. This is the World Tag Title match. [...] Another new chapter in the history of King’s Road Pro Wrestling4 is about to begin.” Those were Kenji Wakabayashi’s words as the Nippon Budokan was bathed in green, orange, red and yellow for the first time. On June 1, Kawada & Taue held their first defense against Misawa & Kobashi; it would be the first of eight tag matches between the four over the next two-and-a-half years. Before the match began, Wakabayashi told Baba that he’d heard the media had already started to call the four the Shitenno. Baba, as Ichinose recalls, seemed to be trying not to shake with joy. Taue would powerbomb Kobashi to retain by pinfall in 29:12.

-

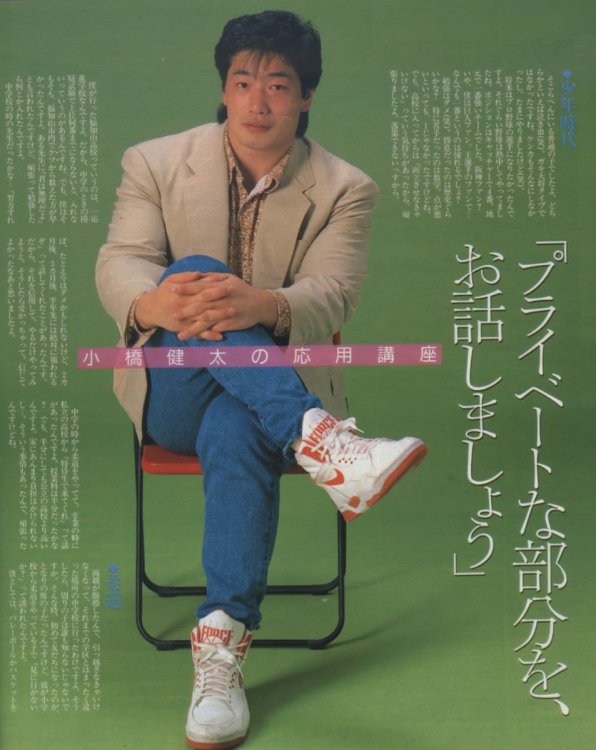

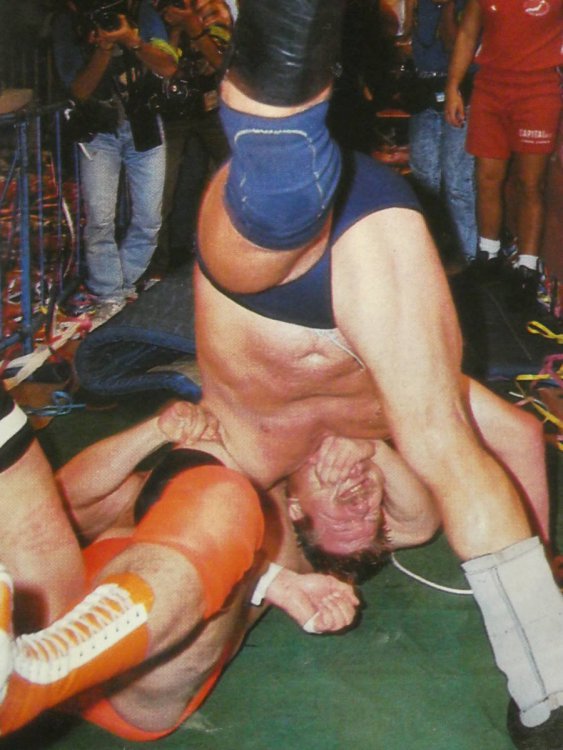

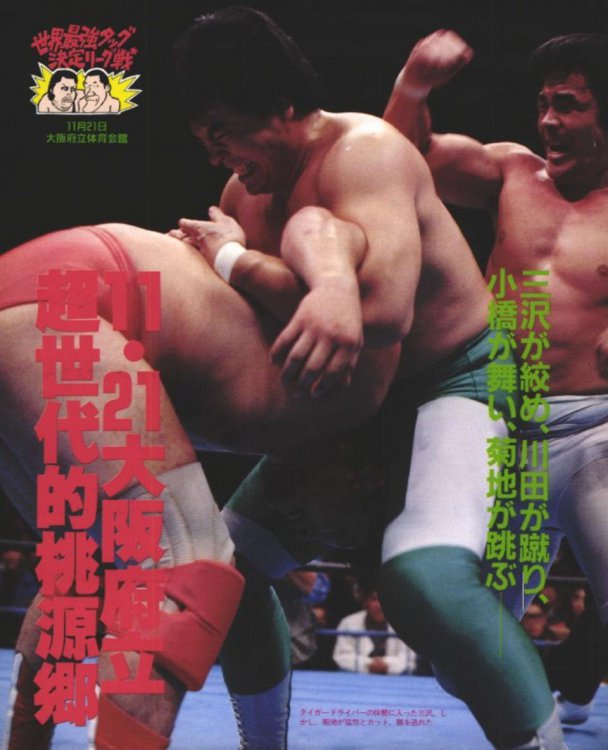

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 18-21, PART TWO For the second post of this batch, we will look at Kenta Kobashi’s arc in the early 90s. ------------ On September 7, 1990, Kenta Kobashi & Johnny Ace defeated the Fantastics to win the tournament for the All Asia Tag Team titles, which had been vacated in the wake of co-champion Shinichi Nakano’s departure from the company. Ace had worked three tours for AJPW in the late 1980s, but that summer he had signed an unusual deal to work fulltime for the promotion [Wrestling Observer Newsletter, 7/9/90]. Ace & Kobashi would enter the 1990 RWTL as a unit, and made their first successful All Asia title defense against the Wild Bunch the following January. Two months later during the Champion Carnival tour, they retained against the Southern Rockers. However, two days later Ace reportedly suffered an avulsion fracture to his left elbow when doing a moonsault on Cactus Jack in a midcard tag match. A second title defense against the Dynamite Kid & Johnny Smith had been scheduled for that tour, and Tsuyoshi Kikuchi was substituted therein; the #4 of the Super Generation Army took a diving headbutt from his idol to end the reign. As Ace made a handful of Stateside appearances which cast doubt on the legitimacy of his injury, from a WWF house show job in West Palm Beach to Col. Mustafa to a street fight against Terry Gordy at UWF Beach Brawl (which went to a double countout), Kobashi & Kikuchi unsuccessfully challenged the Can-Am Express for the All Asia belts in June. When Ace returned in July, he and Kobashi would win the belts back on the 8th before dropping them to the Wild Bunch ten days later, who in turn were transitional champions for the Can-Am Express to swoop in and beat eight days later. Many years later, Kobashi would admit in a book that he had been frustrated by how Kikuchi had been relegated to a fill-in partner. Two days after the All Asia loss, Kobashi teamed up with Misawa to wrestle Stan Hansen and Danny Spivey in Yokohama. While it was the semi-main event of a show in a major market, it would not be broadcast; between the Jumbo/Williams Triple Crown match and a JIP of two-thirds of a Kawada/Taue singles match, I guess Puroresu Newzzzzz cut into whatever time it might have otherwise gotten. However, Ichinose cites this match as a notable one for Kobashi. He recalls that it was a match “without any particular theme”, but Kobashi made it memorable when he broke rank, said “Hey, Stan!”, and went for Hansen’s injured left eye. Misawa followed suit, and soon enough Hansen had juice. Blood had become an unusual sight in the wake of the decree of tanoshiku puroresu (“fun/cheerful pro wrestling”),1 but sure enough, there it was. As for the “Hey, Stan!” part, Kobashi claims he was inspired by how Richard Slinger would greet Hansen like that. He couldn’t go “Hey, Jumbo!” to Tsuruta, but against a foreign wrestler he could drive a wedge in tradition and forego honorifics. Kobashi would pay for his disrespect, earning an assault by chair upon his lower back and submission by crab from Hansen. Deputy Editor Kiyonori Shishikura, who was in charge of the Weekly Pro match report that night, headlined it with “This is the most humiliating way to lose!” However, Kobashi was confident in his postmatch comments: “I was beaten up by Hansen, but I’m young, so all I have to do is train my body to withstand his attacks.” On August 24, All Japan held a b-show at the Sandanike Park Gymnasium in Kobashi’s hometown of Fukuchiyama. It was rare that the promotion came to this northern Kyoto town, as they had not done so since July 1987. It was that year that Kobashi had moved to Tokyo to start his new life, and he had not returned to Fukuchiyama since. Ichinose had asked Kobashi on several occasions if he would do so, but he always got the same answer. Kobashi had resolved not to return to the place of his birth until he had made it. Well, by the time they held that show Kobashi was a regular presence on AJPW television; in other words, he had made it. They rolled out a reliable Chosedaigun/Tsurutagun six-man that night, and in 30:06, Kobashi got the pinfall with a moonsault to Fuchi. The hometown boy bowed deeply to his fans in all directions. Next time he came back, he vowed to himself that he would be a top star.2 Kawada and Kikuchi help Kobashi back to his feet after a postmatch Hansen lariat on August 29, 1991. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #453, dated September 17, 1991 (photograph included in free preview of the issue’s archived digital copy)] Five days later, Kobashi tagged alongside Kawada for a televised (if JIP) tag against Hansen & Spivey. While he was not involved in the result as it was written, he had made it possible by shoving Spivey into the path of a Western Lariat that the gaikokujin had been holding Kawada in place to receive, allowing Kawada to get the pinfall. Despite being scheduled to face Kobashi at the Budokan show in six days, Ichinose recalls that the match started as if Hansen was ignoring his opponent. However, Kobashi’s work upon his arm redirected his attention, and Hansen would brutalize our orange boy. In the aftermath of Kobashi’s clutch save, Hansen would lariat him in revenge. Before September 4, 1991, Kobashi had wrestled Hansen five times in a singles context. The first time, at a February 1990 Korakuen show, he hadn’t even lasted long enough to get on the Cagematch matchguide, as he fell to a lariat in 4:08. Kobashi wrestled Hansen twice that July, losing a televised match at the start of the tour in 12:09 and an untelevised rematch in 11:34. At a Korakuen show the following January, he hadn’t even made it ten minutes. When he entered the Budokan arena that late summer night, the longest that Kobashi had lasted against Hansen was 13:41, in their Champion Carnival encounter on April 15. Kobashi DDTs Hansen onto the exposed floor of the Nippon Budokan on September 4, 1991. [I got this from a Japanese Yahoo! auction listing of photographs from this and another match that just happened to be active while I was writing this.] This time, it would take Stan twenty minutes to put him down. He’d started it in ruthless fashion, ambushing Kobashi with a Western Lariat as referee Joe Higuchi was still checking Kobashi’s person for foreign objects. Hansen hooked his leg for the pin but the match had not begun, and an argument ensued, but by the time Higuchi signaled to Yoshihiro Momota to ring the bell, Kobashi had recovered just enough to begin a roll to the outside. The match which proceeded would present an essential early Kobashi babyface performance, with him surviving two more lariats before the pinfall. They laid it out well enough that the Western Lariat’s reputation as a one-hit kill move was not subverted past credulity, but Kobashi’s perseverance and endurance were nevertheless what defined this match. Their next significant encounter, an untelevised Kobashi/Ace vs. Hansen/Spivey tag on October 24, saw them again mine the outside brutality that had marked their Budokan match, with Kobashi repeating the DDT-to-concrete spot which had consolidated the comeback he had earned then, and Hansen hitting Kobashi’s neck with three connected chairs. That would be the last time Kobashi worked alongside Johnny Ace for half a decade. Not that Laurinaitis would be any less of a presence on AJPW cards in the years to come, but starting with his 1991 RWTL entry alongside Sunny Beach, ol’ People Power would be booked alongside foreign talent until he and Kobashi reunited as GET in 1997.3 When the participants of the 1991 RWTL had been announced six days earlier, Kobashi was nowhere to be seen. This had been Baba’s call, as he was deeply hesitant about booking the 90kg Kikuchi in the tournament. However, Ichinose claims he insisted at a subsequent creative meeting that Kobashi & Kikuchi be added. Even if they had not even won the All Asia titles together, and even if Kikuchi would inevitably drag Kobashi down as far as the results were concerned, Ichinose maintained that fans would want to see them participate. Baba would acquiesce, and after Tsuruta defended his Triple Crown against Kawada in the main event of the October 24 show, Baba gathered the press to announce the last-minute addition of a thirteenth team. The team would only win two league matches, but they did so against teams that had held the All Asia belts that year. On November 28, they avenged their April loss to the Dynamite Kid & Johnny Smith with a Kobashi moonsault to Smith. On the final date, they would beat the Wild Bunch with a Kikuchi bridging German to Billy Black. Ichinose’s confidence in Kobashi & Kikuchi’s connection to the fans would be vindicated even before their first win. On November 21, they faced their Chosedaigun teammates Misawa & Kawada in a block match at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium. This match was mentioned earlier in the book for the Misawa eye injury, sustained during a bar fight with Kawada, that would officially (and extremely dubiously) be blamed on this match. What Ichinose did not mention, though, was that Osaka had been a difficult market for AJPW to attract large audiences. For some time, Osaka residents had clearly known they were playing second fiddle to Tokyo, and attendance had suffered. The November 21 show, though, saw the building filled to capacity. The Super Generation Army match must have been a significant factor in ticket sales. 1992 didn’t see Kobashi reach the highest echelon, but he did show some growth. On one hand, he won the same amount of matches in the Champion Carnival that he had the previous year—three; he got two freebies this year because Billy Black had to cancel last-minute for personal reasons and Taue got hurt—but on the other hand, the one match where he survived long enough for a time-limit draw was against Steve Williams. Two months later, the chase for the All Asia titles would end in Kikuchi’s hometown of Sendai on May 25. The Can-Am Express had held the belts for ten months, with three successful defenses against the Blackhearts, the Wild Bunch, and the State Police. But in a match that the hometown boy would call the best memory of his career, one which he knew had been rated the best match of the year in “some American magazine”, Kobashi hit the moonsault on Furnas to win in 22:11. At the end of the tour, Kobashi received his first shot at the AJPW World Tag Team titles. With Kawada challenging for Hansen’s Triple Crown in the main event, Kobashi was called up to team with Misawa against Tsuruta & Taue. One could bemoan the fact that the last match ever wrestled by a totally healthy Jumbo was arguably more about the relatively fresh Kobashi/Taue matchup than about him; then again, Taue needed a win, and against Kenta he got it. Like the Can-Ams before them, Kobashi & Kikuchi’s lengthy reign would only have three successful defenses; against Fuchi & Ogawa on July 5, against the returning Express on October 17, and against Akiyama & Ogawa on January 24, 1993. However, Kobashi is proud of this chapter in his career. He had always thought that the lower-ranked All Asia titles had had their “own charm”, and he was happy to elevate them alongside his friend. He recounts that the show-stealing January match had been particularly successful at this aim. Kobashi tries to keep Hansen in control on July 8, 1992. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #505, dated July 28, 1992 (photograph included in free preview of the issue’s archived digital copy)] In the meantime, Kobashi would manage once again to make it twenty minutes against Hansen. In a televised warmup match to Hansen’s Triple Crown defense against Taue, the #3 of the Super Generation Army. While he had fallen to the lariat in just under fifteen minutes during their Carnival match back in March, here Kobashi lasted just one second less than he had at the Budokan. Kobashi & Kikuchi would be split up for the 1992 RWTL. Rusher Kimura and Andre the Giant would work that tour, but neither would enter the tournament. Instead, Baba would team up with Kobashi, almost four years after he had worked alongside the then-rookie in Kobashi’s first title shot. Meanwhile, Kikuchi entered alongside Dory Funk Jr, for what would be his final stint in the tournament until he and Tamon Honda went 1-8 in 2010. While Kikuchi would get the same number of wins he had last year, Kobashi & Baba would place fourth, only losing to Misawa & Kawada and the Miracle Violence Connection. Between tours in March 1993, Ichinose conducted an interview with Kobashi, in which he asked him about “taking a step forward”. The journalist knew that someday, Kobashi would be the biggest star in puroresu; it was just a matter of when. But for all of Kobashi’s ambition, 1992 had seen him in what, on some level, seemed like a holding pattern. Kobashi responded that he wanted to “move forward with his fans”. This interview was printed in the Weekly Pro issue dated April 6, and in an excerpt, Kobashi discussed how he wished for his fans to forget about their daily worries when they saw him wrestle: how he wanted to “encourage them” through his fights. Ichinose asked Kobashi whether he believed a main-eventer needed charisma, to which Kobashi responded that he was unsure. Just as the interview ended, though, and as Ichinose was about to stop the cassette recorder, Kobashi said “it’s never a waste of time to think about charisma, is it?” Kobashi won four of his matches in the 1993 Champion Carnival, and went the distance against both the Patriot and Terry Gordy. A freebie due to Jun Akiyama’s early injury brought him to twelve points.

-

As for Akiyama's amateur pedigree, I was surprised to find that the JWF database has no records of him (and I checked both his legal and ring name). It could be a gap in their records, but if he'd been an Olympic alternate I am certain that he would have done well enough in collegiate tournaments to be on there. Edit: according to this he was a runner-up in the All Japan Student Amateur Wrestling Championship.

-

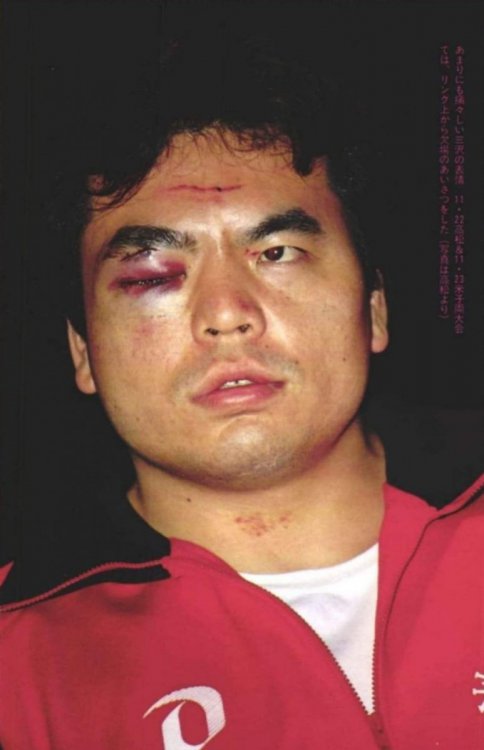

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 18-21, PART ONE I finished the transcription of chapters 18-21, whose 125 pages cover 1993 but make a lot of digressions. This continues to be a book that I cannot recap simply, but I think that what I’ve taken from it will be illuminating. This first post will set the table for the formation of the Holy Demon Army and cover the debut of Jun Akiyama. Ichinose held off on covering a lot of this stuff to streamline the narrative in Part Two, so this goes over a lot of the same ground, albeit from different angles. ------ On March 4, 1992, Akira Taue celebrates the first top title of his career, while Jumbo Tsuruta celebrates his last. 1991-2 were difficult years for Akira Taue. He had grown immeasurably whilst working alongside Tsuruta, and his performances against Kawada in their 1/15/91 and 4/18/91 singles matches had been encouraging. However, Tsuruta and Taue had also lost three tag title matches in 1991, with Taue being booed at the June 1 match against Hansen & Spivey. At year’s end, they were unable to win the Real World Tag League. Taue was the first partner who had failed to notch Tsuruta a RWTL win after two attempts; with Baba and with Yatsu it took him one try (though that’s two for Baba if you count the 1977 Open League), and with Tenryu it took him two. Taue finally won the AJPW World Tag Team titles alongside Jumbo on March 4, 1992, against the Miracle Violence Connection. Jumbo got the pinfall, but Taue had pulled his weight, and for the first time since the summer of 1990, when he had held the All Asia tag titles with Shinichi Nakano before Nakano’s departure for SWS, he had gold around his waist. [2021.10.25 addition: Ichinose later explains how Tsurutagun had earned this title match. For the first tour of 1992, Ichinose pitched a special gimmick to determine the #1 contenders, the New Year Three Team Tournament. Three four-member factions—Chosedaigun, Tsurutagun, and the "Foreign Army" (Hansen, Ace, and the Wild Bunch)—would have all their matches against each other in all configurations tracked, and the team with the highest winning percentage at tour's end would get the contendership. Ichinose admits that he doesn't know how effective it was, but the concept was his attempt to give even local events some modicum of weight in the storyline of the tour, as each would have 1-3 matches which counted towards this percentage.] In the Champion Carnival, Taue would only notch eight points in his block before a neck contusion and ankle ligament injury, suffered during an untelevised Jumbo/Taue vs. Kawada/Kobashi tag, caused him to sit out the rest of the tour and the expanded two-night AJPW Fan Appreciation Day afterward.1 At the end of the following tour, though, Taue pinned Kobashi in Budokan to retain in his first tag title defense. Toshiaki Kawada had received his first shot at the Triple Crown in the wake of Misawa’s nose injury. Likewise, Taue would challenge for Hansen’s belts during the Summer Action Series, where Tsuruta was out with an “ankle injury”. Like the Kawada match, as well as Misawa’s first Triple Crown shot in July 1990, Taue’s first challenge for AJPW’s top prize was held at a medium-sized venue as per Baba policy. Anyway, a buildup tag on a July 5 Korakuen show had seen Taue and Hansen square off, respectively partnered with Rusher Kimura and Billy Black. During this match, about half of which aired joined-in-progress, Hansen fractured Taue’s left orbital bone, dislodging his eye. (To this day, Taue says that when his eyes are in motion, “it’s like he’s only seeing out of his right side”.) However, perhaps due to the pressure that Tsuruta’s absence had brought upon the tour, Taue would not miss a single date, even though Hansen took the July 20 show off due to back problems. At tour’s end, at the Athletic Park Gymnasium in Matsudo, Taue fell to the Western Lariat in 14:41. As covered in my previous batch of posts recapping this book, Taue lost a #1 contendership match to Kawada on September 9, but postmatch comments suggested that Kawada had reached a certain respect for his rival. Eight days later, AJPW booked Korakuen for a 20th Anniversary show in between tours. This five-match card saw Taue team with Mitsuo Momota to go over Motoshi Okuma & Haruka Eigen in the third match, due to Giant Baba taking what would have been his spot in the main-event Chosedaigun/Tsurutagun main event. Alas, the show would best be remembered for the match in between. SUPER ROOKIE Above: On February 3, 1992, Giant Baba held a press conference at Senshu University to announce his signing of Senshu wrestling team captain Jun Akiyama. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #479, dated February 18] Jun Akiyama1 was born in Izumi on October 9, 1969. Not much about his family is disclosed, but we learn that, like Kawada, Akiyama’s first exposure to pro wrestling was through his grandpa’s television. He didn’t loathe wrestling like Kawada originally did, having pleasant memories of watching all the primetime wrestling there was, and he as so many others was struck by Tiger Mask’s rivalry against the Dynamite Kid. Akiyama was a swimmer until he entered Takaishi High School, at which point he switched to judo. However, the school’s wrestling coach invited him to train with them. By his sophomore year, he was a member. The early stretch of Akiyama’s Wikipedia biography, which cites a 2016 magazine of wrestler biographies, contains a recollection that his advisor, Shunji Shiraishi, had been trying to lead him and his friends towards the wrestling team from the beginning, as when they asked him to talk about the judo club he changed the subject. The wrestling team practiced far more than the judo club, but Akiyama stuck with it. Akiyama competed in the junior division of the 41st National Sports Festival2 in 1986, wrestling freestyle at the 81kg class. According to a PDF of 1946-2010 festival results, he would place third in the division, which was won by future Pancrase fighter Kazuo Takahashi. Upon his graduation, Akiyama enrolled at Senshu University and joined its wrestling team. As a freshman he shared a dorm with senior year teammate Manabu Nakanishi, about whom Akiyama has nothing but good things to say. Unfortunately, Akiyama would not see the same amateur success as his four-time national champion and Olympian roommate. A knee injury would derail his junior year, and the Senshu team would be knocked down a division. The early 1990s saw NJPW recruit several successful collegiate wrestlers. The aforementioned Nakanishi was joined by Hiroshi Nagata of Nittatsu University and Waseda’s Tsunemitsu Ishizawa. Riki Choshu’s increased backstage importance appears to have been the impetus, and Akiyama recalls that, while he wasn’t aware when it happened, the promotion had dispatched Hiroshi Hase as a talent scout. Akiyama was not as successful as any of those three. Although he would become team captain as a senior, his attention was divided by the shukatsu system of job-hunting. He was considering a job offer from an unnamed Osaka company, which planned to start its own wrestling team. However, another option arose one night in July 1991, when head coach Kenshiro Matsunami invited Akiyama to a dinner at the Capitol Tokyu Hotel. This was the first time Akiyama met Giant Baba. “He talked to me about wrestling, money, and all sorts of things, but the thing I remember most was, ‘Don't worry about anything, just come.’” Baba would meet with Akiyama’s parents and give a talk at his high school, in a rare amount of effort to gain a new recruit. Jun was not immediately swayed, and would continue to consider his job offer. His old high school advisor had suggested he look into pro wrestling, having held the dream himself in his youth, but Akiyama had never truly considered it. But after an interview with a top executive, the two happened to take the same bus back home, and Akiyama saw how much the salaryman lifestyle had worn this man down. He thought that he didn’t want to be like that when he was forty, and the experience compelled him to give pro wrestling a chance. On February 3, 1992, Akiyama’s signing was announced in a press conference at his alma mater. Not since Hiroshi Wajima had AJPW gone to such trouble to display a new member, and it made Baba’s high expectations clear. Akiyama’s training was apparently a smooth process. The grounding in ukemi4 that Baba considered paramount in the All Japan training pipeline usually took a trainee three to four months to master, but Akiyama had it down in less than one. About four months in, Baba would assign him to supplemental pre-show practice sessions with foreign wrestlers such as Johnny Smith. Such sessions did take place between fellow native wrestlers, but it was rare that a foreign talent would participate in the process; Akiyama suspected then that this was special treatment. Ichnoise points out that, up to this point, AJPW debut matches had followed one of three templates. The most common was a preliminary singles match; most start from the bottom, and Akiyama had figured that he would as well. For the select few who had been groomed to immediately become major players, All Japan had taken two paths. The first was a match against a foreign wrestler, usually a midcarder. Jumbo Tsuruta had debuted in Amarillo by going over El Gran Tapia, and his first AJPW match repeated this pattern against Moose Morowski. The second and much more common approach was a tag match alongside Baba against two gaikokujin. This had first been done with Anton Geesink in 1973, against the team of Bruno Sammartino and Caripus Hurricane (AKA Ciclon Negro). Although Tenryu had debuted in an Amarillo singles match the previous winter, his first AJPW match was a 1977 tag with Baba against Mario Milano and Mexico Grande. Hiroshi Wajima’s first matches were tags abroad alongside Baba, which were contemporaneously broadcast in Japan, although his debut match in AJPW itself was against Tiger Jeet Singh. Finally, Akira Taue debuted in a tag match with Baba against Buddy Landel and Paul Harris, on the first show of 1988. If the plan was to debut Akiyama at the 20th Anniversary Korakuen show on September 17, 1992, and they weren’t going to relegate him to a curtainjerker bout, they would have no foreign talent to book him against due to the show’s placement in between tours. The pressure was on to book a memorable match to mark the occasion, and though Ichinose could only go by Ryu Nakata’s word that Akiyama would be a good wrestler, he pitched a semi-main singles match between Akiyama and Kobashi during one of the secret creative meetings. Ichinose admits that he was inspired by NJPW’s Yume Kachimasu, a special show first held in 1989 that gave Young Lions the chance to wrestle veteran talent. Baba was quite reluctant, but despite the certainty that Akiyama would start his career with a loss, Ichinose would not be deterred, and the match was approved. Akiyama was told that he was debuting at the 20th Anniversary show two weeks in advance, and informed of his opponent two days in advance, but the outside world would not know about it until the show itself. I attached this photograph to the mention of Akiyama’s debut in my last recap post, but I need to discuss the moment it captured directly. Akiyama was highly praised for his performance at the time, and the match continues to be quite respected in the Western fan community as one of the best debut matches in wrestling history. However, it was not a genuine expression of Akiyama’s self. Akiyama strongly implies that the moment in the photograph, in which he “barks” at Kobashi on one knee after having taken a string of chops and kicks, was a Kobashiism that the two had come up with beforehand to “bring out Akiyama’s expression”. From the comments excerpted here, Akiyama will be the first person to tell you that the match was a Kobashi carryjob, and though they crafted a satisfying match, Akiyama knew that that hadn’t been the real him out there. In keeping with his superrookie status, Akiyama would work every date of the ensuing October Giant Series tour. Due to the odd-numbered roster of the time, Akiyama was being booked more consistently in his first tour than Satoru Asako and Masao Inoue, both of whom had debuted in the spring of 1991, or even twenty-year veteran Mitsuo Momota. Booked exclusively in regular and six-man tags, Akiyama would share the ring with most of the significant talent to work that tour. From the top native stars of Chosedaigun and Tsurutagun (Akiyama mainly worked as an unaffiliated teammate of the former, though he did work one six-man on the other side during the tour’s antepenultmiate show), to the foreign stars of today (Stan Hansen) and yesterday (Dory Funk Jr, Abdullah the Butcher), Akiyama worked with more big names in a single tour than most puro rookies do in their first two years. As the last-debuting AJPW wrestler to work against a relatively healthy Tsuruta, Akiyama took his backdrop for the pinfall on October 13; five days earlier, he had been “baptized” by the Western Lariat. All the while, Baba fed him high-calorie dishes, likely insisting that Akiyama be an ebisu as he had Kobashi. As covered in the previous post, Akiyama was thrust into Tsuruta’s spot in the 1992 RWTL after Tsuruta’s hepatitis struck. By his own recollection, Akiyama didn’t stop to think about it, and just did what he had to do. He felt he had no choice, which wasn’t helped by his feeling that he was, in a sense, Tsuruta’s understudy. (As mentioned in a much earlier post on this thread, Akiyama claims that he suspected that Tsuruta’s health would go south.) Akiyama & Taue would have a 6-3 record at the tournament before advancing to the finals. On a November 17 b-show, Akiyama won his first match by pinning the Eagle in a six-man. It was only his 22nd match, which by AJPW rookie standards was doing pretty well. He even got to win one of the tournament matches, as he pinned Kendall Windham with a bridging German suplex on November 21. However, hierarchy would rear its ugly head for all three of their tournament losses; Akiyama was felled by Hansen’s Western Lariat on November 20, by Steve Williams’ Oklahoma Stampede on November 27, and by Kobashi’s moonsault on November 30. On December 6, 1991, Akiyama was one of 15,900 Budokan spectators to witness the last RWTL show, in which Misawa & Kawada and Tsuruta & Taue competed. He could never have fathomed that, just one year later, he would take the place of one of those four at the same venue. On December 4, 1992, he had 16,300 eyes on him. Three months earlier, he had wrestled his first match, and twelve years later, he would headline the Tokyo Dome, but Akiyama states that this was the most nervous that he would ever be in his career. It was a match that was destined to be a deflating experience from the moment Akiyama took Tsuruta’s place, but he had a good showing in his 36th match. (Note that Misawa and Kawada were both putting over Yoshihiro Momota in the undercard on their 36th matches.) If Cagematch is to be believed, the 1993 New Year Giant Series tour was when Akiyama was first officially billed as a member of Tsurutagun. This tour would also give him his first title match, a shot alongside teammate Yoshinari Ogawa at Kobashi & Kikuchi’s All Asia tag titles. Finally, it would give him the platform to have some more singles matches, through the seven-match Trial Series. Like Kobashi at the start of 1990, Akiyama would go 2-5, with wins against Al Perez and Johnny Smith to punctuate losses to Misawa, Kawada, Hansen, Gordy, and Williams. The longest of these matches was against Kawada, at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium on January 26. Five days earlier, after a Taue/Akiyama vs Kawada/Kikuchi tag, Kawada had criticized Akiyama as a mechanically sound but inexpressive wrestler, not cut out for the elite. After pinning Akiyama with a powerbomb in 14:37, Kawada maintained his position: “You’ve got all these moves; now it’s time to learn to wrestle.” Kawada’s criticisms clearly were not spiteful. Four years earlier, when Ashura Hara’s dismissal had forced him to step up to the main event, Tsuruta had subjected him to a similar trial by fire. But Akiyama was cursed by his superrookie status, and though he commented after the Kawada match that he now understood that the “feeling that you put into each and every move” was the most important part of wrestling, he would be slow to implement this. Much later, Akiyama would admit that he had also been affected by the persistent criticisms in Ichinose’s Weekly Pro writeups, which stated, again and again, that Akiyama had shown “no color”. On March 11, one week after the end of the 1993 Excite Series, Ichinose interviewed Akiyama for the first time. This would be published in the Weekly Pro issue dated March 30, under the title “A Letter from the Spring Breeze”. Akiyama expressed his self-consciousness about his position. It appeared that the 1993 Champion Carnival would give Akiyama a chance to further grow as a wrestler. However, in the second match of the tour’s first date on March 25, Akiyama injured his right arm. He would not wrestle for two months, and would return to a much different landscape. A PARTNERSHIP OF RIVALS “I always hated pro wrestling. Really, I hated it. I wonder to myself why I fell in love with it so much. [...] I don't have any feelings of love or hate right now. But the fans still come back, so it must be attractive.” (Toshiaki Kawada, June 1992) The book continues to frame Toshiaki Kawada’s departure from the Super Generation Army as his own decision. Whether or not this is kayfabing the matter, Ichinose’s narrative lays out Kawada’s anxieties convincingly. In his February 28, 1993 postmatch interview with Ichinose, during which he stated that there was a “50/50 chance” that he would leave Chosedaigun, Kawada admitted that he felt pigeonholed by the success of the Super Generation Army in the media and among the fans. He expressed no resentment towards his teammates themselves, but he clearly felt he had gone as far as he could alongside them. Kawada also brought up his belief that wrestling had a three-year cycle. Ichinose points out that the Super Generation Army had formed in 1990, and Revolution three years before that. (You could take this back even further. Japan Pro Wrestling was formed in 1984. 1981 had seen three of the biggest foreign names in puroresu—Abdullah the Butcher, Stan Hansen, and Tiger Jeet Singh—change allegiances, on top of the IWE’s demise and its fallout. As for 1978...uh, I mean, that’s the year that Fujinami became a star, as well as when the IWE burned their bridge with Baba and got into what would be an even more asymmetrical partnership with NJPW. Not as great an example, but you get the idea.) While he brought up his three-year cycle theory, Kawada had openly worried about the potential staleness of the AJPW product as early as 1991. In an interview with the author after that year’s August 11 Korakuen show, after he and Tsuyoshi Kikuchi defeated the Blackhearts, Kawada said that a few shows that tour had not sold out, which made him nervous. As he would say in the February ‘93 postmatch interview, Kawada did not want to go back to the days when he would wrestle for fifty people. AJPW’s momentum insofar as box office was concerned had not yet stalled, but Kawada’s fears were not unfounded. Ichinose compares the first tours of 1992 and 1993 to demonstrate this, going by official statements. In 1992, All Japan held 19 shows; only two of these shows were “unmarked”, and 14 of the remaining 17 were not just full, but sold out. Meanwhile, the 1993 tour held 23 shows. 12 of them were sold out, and four were full, but this time almost a third of the tour’s events were “unmarked”. The greatest indictment was a comparison of the respective tours’ shows at the Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium. On January 21, 1992, a card headed by four Chosedaigun vs. Tsurutagun singles matches drew 6,150. On January 26, 1993, with a Kobashi/Taue main event, a Miracle Violence Connection tag title defense against Hansen & Spivey, and the Akiyama/Kawada trial match, AJPW only drew 4,100. Once again, Baba entrusted Ichinose with booking the 1993 Champion Carnival; this time, though, Baba lifted the two-block compromise that he had imposed upon the tournament’s revival two years earlier. Ichinose thought that he had done a good job, but complaints came early. On the first show of the tour, a March 25 Korakuen date, a Kawada-Williams match was the last of the three tournament matches. It went to a thirty-minute time-limit draw, despite a Williams backdrop hurting Kawada’s neck halfway through. After a Chosedaigun/Tsurutagun six-man tag on the following night’s untelevised Korakuen show, Kawada spoke to reporters while nursing his neck with an ice pack. He recalled how, in the 1992 Carnival, he had been forced to wrestle Williams just one day after Hansen in consecutive block matches, which had been difficult for him. He stated that he didn’t blame the powers that be for booking him against Williams to start the tournament, because they clearly needed to elevate someone. Ichinose took this comment as a reporter—none of the talent save for Baba knew of his creative influence—but he and the other reporters in the room were shocked by it. Ichinose compares it to Riki Choshu’s famous (if allegedly apocryphal) comment in 1982 that he “wasn’t Fujinami’s bait dog”. After Misawa won his tournament match that night against the Patriot, he responded to Kawada’s remarks: “There's a part of you, Kawada, that's not quite brave enough. If you're leaving, why don't you just say so? He can't make that final decision. He can do it if someone else does it for him, but he can't do it himself. It's always been that way.” The following night, Misawa and Kawada faced each other in a Kyoto tournament match, which Misawa won with an elbow in 22:00. At the April 12 show in Osaka, Kawada and Taue wrestled as members of opposing factions for the last time. It was on this show that Kawada announced he would leave the Super Generation Army, although he expressed gratitude for their support. Two days later, during a press conference held at a Nagoya show, Baba confirmed that he would be joining Taue’s team, and stated that he wanted the two to challenge for the tag titles. Kawada had requested one last six-man tag alongside Kobashi and Kikuchi, and in the semi-main of the tour’s final show (April 21, Yokohama), they wrestled Tsurutagun in a match that saw Fuchi sit down on a Kikuchi sunset flip attempt for the pinfall. By Kawada’s own admission, the match was uninspired. Afterwards, he asked Wada if he had counted a bit fast, to which the referee responded: “I think it’s good that your last match was so dull.”

-

Comments that don't warrant a thread - Part 4

KinchStalker replied to TravJ1979's topic in Pro Wrestling

Fujinami didn't adopt the ring name with different kanji until he came back from the hernia, so I think it's him; sure, he's now wrestled longer under it than not, but he wrestled under his real name for the entirety of the Showa period phase of his career (that is, the stretch of his career when wrestling had the most cultural relevance). Kobashi also did his kanji change later on. -

NEW INFO ON EARLY IWE I've finished transcribing the next four chapters of the Pillars bio, and am currently sifting through the material to figure out the best way to distill and arrange it. In the meantime though, Igapro just posted a historical post with a couple new pieces of info on the earliest days of the IWE. I put my IWE history project on indefinite hold when I managed to get a copy of the Pillars book—and after Herr Sitemeister tweeted this, I fear that it may become my brand—but this shit is too good to keep to myself. I plan to eventually incorporate it into a rewrite of the first IWE history post It looks like Hiro Matsuda had ulterior motives during his short tenure for the IWE. He had been made director of the promotion upon its formation, and on top of making the merger with the flailing Tokyo Pro Wrestling happen due to his connection to Antonio Inoki, Matsuda''s link to Eddie Graham (who wasn't running Championship Wrestling From Florida yet, but was already involved in its booking according to the Hornbaker NWA book) made him an effective booker. (Note that I am using "booker" in the classical puro industry sense; a booker scouts and secures foreign talent to work a tour, while a matchmaker puts the shows together. It's possible that Matsuda was also the matchmaker, but the word "booker" is always used in the former context in these stories.) Graham himself worked on the IWE's first tour, and it was he who allowed the Danny Hodge NWA junior title defense against Matsuda to take place. As it turns out, Graham had Sam Muchnick's approval for all of this. Like Al Karasick, the Hawaiian promoter who sought to wrest control of the JWA from Rikidozan, Graham's ambition was to take over the IWE. Apparently, Matsuda was in his corner because he was disappointed in how his original plan to break from the sumo-inherited hierarchy of JWA puroresu in favor of an American-style freelance system had been abandoned. Graham applied on Kokusai's behalf for NWA membership, the plan being to become a stockholder and eventually oust Isao Yoshihara. However, the combination of Inoki's departure, TBS's cold feet in going ahead with a broadcast deal, and Kokusai's already large debts due to talent salaries led to Matsuda and Yoshihara's fallout over the handling of said debt, though it is unknown whether Yoshihara was aware that Matsuda had sought to betray him. The JWA would maneuver to acquire NWA membership that year, and whatever Muchnick's reasons for approving them instead, Graham would order Matsuda to withdraw and return to the States when his plans failed.

-

I can't find any direct answer on who made the call. It's clear that the superteam was necessary for hierarchical purposes; if Jumbo vs Tenryu is your main program, you need Tenryu to have a good chance of beating him in tag title matches as well as singles, and they just were not going to book Kawada that strong. That being said, the original card for the 1988 Budokan show that became the Bruiser Brody Memorial Night came to the fan-voted dream tag of Jumbo/Brody vs. Hansen/Tenryu, and I see the decision partially as a way to make at least half of that a reality.

-

Bix said I should start a blog to make this stuff easier to organize, and I agree. I was going to put this off until I had some more content in the pipeline, but fuck it. From Milo To Misawa will start with an expanded and rewritten Jumbo biography, and the first part is already live. Eventually I would like to transfer all the content here onto the blog, but the Jumbo redux will honestly be the main attraction for a while. I probably need a break from the transcription game because, while pushing myself to complete the remaining 400 pages before the New Year is a bad idea, it's a seductive bad idea, and forcing myself to revisit what I now consider to be my worst work on this thread will be ample distraction. However, I will post other new content to this thread when I have some, at least for the foreseeable future.

-

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 10-17, PART EIGHT This will be the final post covering the second half of part two of the Pillars book. --------- Tarzan Yamamoto’s suggestions to make Korakuen Hall a priority of the company had paid off. By early 1992, these events were selling out so quickly that AJPW began to cater to those who weren’t fast enough, through a postcard lottery system for a certain number of seats. “I CAN’T REST ANYMORE” Above: after Mitsuharu Misawa was legitimately injured in a Korakuen six-man tag on July 21, Toshiaki Kawada was substituted in his place. Three nights later, a local promoter threatened to lower his payment for the AJPW show he had purchased if Misawa took the night off, and Misawa was pressured to work the rest of the tour in a sling. On the March 4 Budokan show, which reportedly set an attendance record of 16,300, Misawa lost his third shot at the Triple Crown to Stan Hansen. Six weeks later, in the final match of the Champion Carnival, he lost to Hansen again. The August 22, 1992 Budokan main event would be Misawa’s fourth Triple Crown shot, his fifth singles match against Hansen. Yet, it would also be Hansen’s fourth defense of his titles. In his comments before the match, Misawa vowed that he would not challenge for the titles for a full year if he lost again. One month earlier - on the July 21 Bruiser Brody memorial show in Korakuen, to be exact - Misawa had led Chosedaigun in another six-man tag against Tsurutagun. Jumbo Tsuruta was absent from the tour, for what was then reported as a reaggravation of an old leg injury, so they had the advantage going in. However, this was derailed when Taue legitimately injured Misawa’s shoulder (specifically, Misawa suffered a dislocated acromioclavicular joint). Kawada was substituted in to restart the match. Misawa would take the following night off, a show in Tsushima; however, when the local promoter for the July 24 Izumo event threatened to dock his fee for the show due to Misawa’s absence, Baba asked him to return. At that point, Misawa would later recall his feeling that “he couldn’t rest anymore”. Misawa would work the last seven dates of the tour in a sling. At the very least, he would get a little rest before his title shot, as the Summer Action Series II tour would start nearly three weeks after the Summer Action Series I tour had ended on July 31. However, his title match would only be his third of the tour. Above: Misawa hits Hansen with the hardest elbow he has to win the Triple Crown Heavyweight Championship. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #511, dated 9/8/1992] Ichinose recalls arriving at the Budokan on August 22. What struck him was that the long, long line that he had seen upon his entrance was not for the ticket office, but for advance ticket sales for the next AJPW Budokan event: the promotion’s 20th anniversary show on October 21. Ichinose was genuinely moved by how far the promotion had come since the bleak aftermath of the SWS departures. As you likely know if you’re reading this, this was when Baba finally put the belts on Misawa. Ichinose’s remarks on the match aren’t particularly revealing, though he was as surprised as anyone by the elbow strike finish. Misawa's postmatch comments frame the match as being as much his battle against his own body as that against Hansen. ROAD TO THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY Above: On September 9, 1992, Kawada and Taue face off in a #1 contendership match to be Misawa’s first challenger. In an August 28 interview with the author during an Osaka show, Misawa admitted that he had not yet proven to himself that he deserved to be the champion, a statement which was in keeping with remarks he made after his victory over Hansen. Misawa’s first defense was scheduled for the October 21 Budokan show, but a #1 contendership match in Chiba on September 9 would determine whether his challenger was Kawada or Taue. In his postmatch comments on August 22, when asked which of those he would rather face, he responded “...you're waiting for me to say Kawada, aren't you? Then write that down. I think Kawada is the one worth wrestling at this point.” There was, however, hesitation baked into his remarks. Meanwhile, Kawada stated at the 8/22 show that, if he won the contendership match, he wished to use a separate locker room before their title match, because he believed that he would need to isolate himself from his partner to have a match that would satisfy their audience. Misawa disagreed, as at the August 28 show he responded that the two could save their feelings until the day of the match. It was a difference in ideologies; Misawa believed that they did not need to take this measure because they had a smooth relationship, while Kawada believed that it was because they had a smooth relationship that he had to do this. Ichinose recalls how Revolution had gotten their own tour bus to reinforce their separation from the main unit of the roster, and how in the faction’s earliest days as just a tag team, Genichiro Tenryu and Ashura Hara traveled separately to smooth their transition from rivals to partners. Ichinose also notes that Kawada’s belief that distance was necessary was sympathetic to Baba’s own sensibilities. After all, the “ippon hanamichi”, the single entrance stage and ramp, was a development in the presentation of professional wrestling that Baba despised and kept out of his product for as long as he lived; whether post-Baba All Japan was to continue the tradition of having wrestlers enter through the first and third doors of the venue would be one of the irreconcilable differences between Misawa and Motoko which brought about the NOAH exodus. Ichinose became anxious that Kawada might not give a comment if he were to win the Chiba match, so he decided to interview him at the b-show in Nagano on September 8. It was here when Kawada gave further insight into his anxieties. In their interview, which would be published in the Weekly Pro Wrestling issue dated September 29, 1992, Kawada admitted that he was worried that, if he won the #1 contendership and then challenged Misawa, then that would be the end of it. He would still be a member of the Super Generation Army. He didn’t see where the story could go from there. In short, he was afraid that, ultimately, “nothing would happen”. The following night, Kawada wrestled Taue as planned. This match appears to have been (Ichinose doesn’t mention it) the debut of Kawada’s signature entrance theme, the original composition “Holy War”; this was after two years of using “The Last Battle”, a minute-long piece of music from the anime adaptation of motorbike racing manga Bari Bari Densetsu. As for the match itself, Kawada won in 18:46 with a stretch plum. In his postmatch comments, Kawada declined to comment on his thoughts about wrestling Misawa, proving Ichinose’s hunch correct; instead, Kawada was interested in expressing his gratitude that he and Taue got to wrestle the main event of the last show of the tour. Both of them had worked hard, and he hoped that they could both make it to the top. Above: Jun Akiyama debuts at the 20th Anniversary show in Korakuen. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling Issue #515, dated October 6, 1992] After a September 17 Korakuen show to celebrate the actual 20th anniversary of the company, which saw the debut of Jun Akiyama as well as a unique Chosedaigun/Tsurutagun six-man with Giant Baba tagging alongside Tsuruta and Fuchi, the 20th Anniversary Giant Series tour began with another Korakuen show on October 2. 10/21/92 As has already been established, the seventeen-date tour ended at Budokan. While not contemporaneously broadcast in full, it was a relatively early example of an AJPW show that we know was professionally taped in full, as it would be broadcast many years later. Besides the main event, the most interesting match was the semi-main event. While it was a six-man tag with mostly old and/or limited performers, the Baba/Hansen/Dory vs. Andre/Jumbo/Gordy match was positively received when announced due to the twist of trading Hansen and Tsuruta. Ichinose claims credit for the idea. In his recollection of the match itself, Ichinose points out a “mischievous” detail: Baba’s use of the Mongolian chop against Andre, which recalled Andre’s NJPW/WWF feud(s) with Killer Khan.[1] Kagehiro Osano’s 2020 Jumbo biography features claims from Masanobu Fuchi that one of the plans for this match’s finish was to have Jumbo finally pin Baba. However, they settled on having Tsuruta finally go over his teacher Dory. Kawada’s request for a separate waiting room had not been granted until this last show. From the start of the event, he had declined all interviews, though Akira Fukuzawa predicted that he would be very talkative in the ring. Before his Mexican excursion, Mitsuharu Misawa had wrestled Toshiaki Kawada four times in a singles context. He had won all four matches: the first three by pinfall, the last via submission (single-leg crab). That had been on October 18, 1983, almost exactly nine years before this match. Above: various photographs from Misawa and Kawada's first singles match in nine years. Thirteen minutes into this match, a spin kick gave Misawa a concussion. This match too would see Misawa battle himself, and he would admit that he could not remember the second half of it, or even the precise point at which his memory faltered. Misawa would also admit in postmatch comments to NTV interviewer Shigeru Kaneko that he didn’t feel like he had won the match. The copy for Weekly Pro’s feature on the match, in what may have been the first AJPW special issue printed by the publication, read “The Door of Dreams”. Their coverage read that this match, or perhaps more accurately, the fact that Misawa and Kawada could have had that match without the heat of rivalry to draw upon, had opened such a door for a new era of professional wrestling. And yet, the match would not be chosen for Tokyo Sports’ Match of the Year, which instead went to Kawada’s June 5 title shot against Hansen. Whether or not this was influenced by Misawa’s attitude towards the ceremony, Ichinose cannot confirm. POSTSCRIPT Above: Misawa & Kawada win the Real World Tag League on their third attempt together. This photograph may have been a candidate to be the cover photo for the Weekly Pro Wrestling issue covering the tournament final; however, in an indictment of the disappointing year-end show, Tarzan Yamamoto instead decided to give the cover to new UWF International signing Naoki Sano. This photo would instead be featured on the cover of a calendar feature (or included calendar, I don't know) in the last issue of the year, dated for the first two weeks of 1993. This section of the book ends with light coverage of the next four or so months, and the picture of stagnation they painted. With Tsuruta’s post-tour hospitalization, Taue was partnerless as the 1992 RWTL approached. While Fuchi, Mighty Inoue, and Rusher Kimura were seen as options, Ichinose and Yamamoto recommended that rookie Jun Akiyama be called up instead, to establish him as a valuable future asset. Baba hesitated but eventually agreed. Taue & Akiyama reached the finals, where they were defeated by Misawa & Kawada. The match itself was decent, and Ichinose’s Weekly Pro recap was favorable on those terms, but Yamamoto’s commentary in an editorial forty pages earlier was harsh, writing that “[the year-end Budokan show] scored zero as an entertainment event”. As Tsuruta’s absence continued into the new year, the product remained stale, and by late February, Kawada’s dissatisfaction was visibly bleeding into his performances. After the Excite Seres' Budokan event on February 28, in which he had wrestled Hansen, Kawada was frank with Ichinose: “It's boring. It's boring for me, it's boring for you. For them, it's like watching the sequel of the same movie over and over again. They can see what's coming, and it's not interesting. If I were a customer, I wouldn't want to see it again.”

-

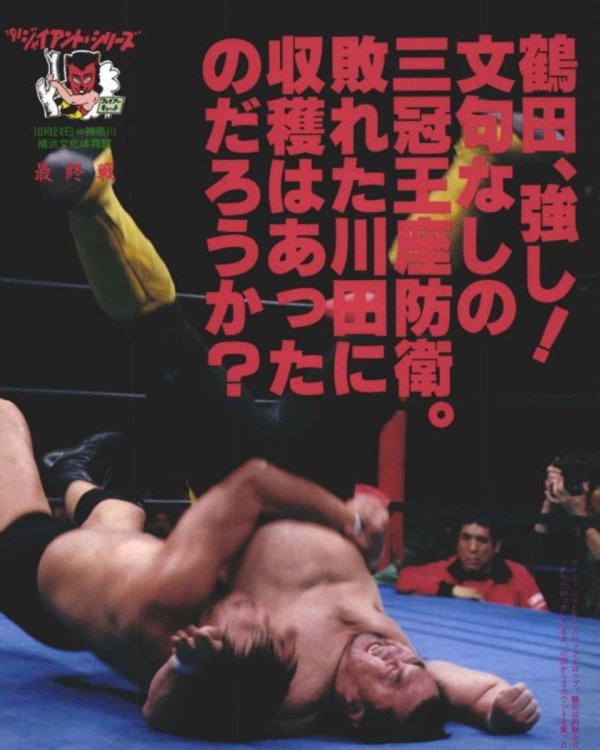

2019 FOUR PILLARS BIO: CHAPTERS 10-17, PART SEVEN “WHEN HE FIGHTS LIKE THAT, HE’S BETTER THAN MISAWA” Ichinose cites a handful of 1991 matches in the context of Toshiaki Kawada’s efforts to develop his own style. The earliest of these is his Champion Carnival match on April 6 against Jumbo Tsuruta, a match whose finishing stretch hinged on Kawada’s persistent kicks to Tsuruta’s face. After winning in decisive fashion, Tsuruta was nevertheless encouraging of Kawada. “When he fights like that, he’s better than Misawa.” On July 6, during a Misawa/Kawada vs Tsuruta/Ogawa tag match in Yokosuka, Kawada was injured by Ogawa’s step kicks (Ichinose reports it as a broken left orbital bone, though in the broadcast one sees a bloodied mouth). Two weeks later, Kawada faced Taue in their first singles match in three months, which broadcast as a joined-in-progress clip of approximately the last ten minutes. Much of this match saw Kawada fight with “primitive striking”, before finishing the match with a choke sleeper hold after a powerbomb kickout. After this match, Kawada made a comment that Ichinose considers reflective of the wrestler he was becoming: “I wonder if wrestling is not about techniques. Sometimes, you get better results when you can’t execute your moves.” When Kawada was called up to challenge for the Triple Crown in Misawa’s place, though, he tried a different approach. Ichinose’s match report noted that Kawada moved away from the kick-heavy approach he had been developing, in favor of repeated use of strangulation techniques. In a November 9 interview with Ichinose, Kawada stated that he mixed up his approach because he wanted to minimize his mistakes, feeling that Tsuruta would be able to read his moves and neutralize him if he went to the kick well. But to paraphrase Kawada, he only ended up strangling himself. Eight months later, Kawada received his second shot at the Triple Crown. On June 5, 1992, Kawada challenged Stan Hansen at Budokan. Almost exactly two years before, Kawada had wrestled Hansen in a Sapporo squash match. That match had also seen Kawada adopt a kick-based approach early on, though everything had gone wrong for him when he tried to counter an apron suplex with an O’Connor roll. In 5:03, was pinned after a Western Lariat. The Budokan match would see him last four times as long. In contrast with 10/24/91, Ichinose writes that Kawada succeeded in expressing his style and philosophy in this match. Kawada’s wrestling throughout the match was most certainly not about techniques, taking it to Hansen with a strike-heavy approach. Hansen responded in kind, as Hansen is wont to do. While Kawada stated after the match that “Hansen was not the man he wanted to fight”, as “he didn’t like to fight foreigners”, Hansen’s meat-and-potatoes approach satisfied Kawada. “It meant that he had been accepted, or rather, forced to accept himself. Hansen places the NWA United National title belt upon Kawada's shoulder after their June 1992 match. [Source: Weekly Pro Wrestling #399 (dated June 23, 1992)] As Hansen left the ring, Kawada went after him while selling the damage he had sustained. When he finally caught up to Hansen, he offered a handshake, which Hansen took. Just then, Kawada collapsed, and Hansen responded with a respectful gesture, lightly placing one of his Triple Crown belts—the NWA United National title, the secondary singles title which had chiefly been held by Jumbo Tsuruta and then Genichiro Tenryu in the thirteen years before the Triple Crown unification—upon Kawada’s shoulder. "When I fought Hansen in Sapporo, I felt that I wasn't worthy. To be able to fight Hansen at the Budokan was unthinkable in the past, so I guess I wanted to go toe-to-toe with him. No other foreign wrestler had ever responded to me in that way, and that's why, after the fight, I wanted to go see Hansen. I hadn't thought much of Hansen before that. I hadn't had a good image of him since I was a new apprentice, because he knocked me down by a lariat when I came in to stop a brawl, but when he fought me head-on at the Budokan, I was grateful.” When he recovered, Kawada called an ambulance to further sell the effects of the match. His comments in a June 10 interview with Ichinose make it clear that, by this point, the expression of accumulated damage had become a focal point of Kawada’s performances, comparing his efforts to “convey the pain of a wrestler” to a television audience to how a cooking show may attempt to convey the smells and tastes of the dishes. During his third Triple Crown reign, Hansen would successfully defend his belts against three of the future Shitenno: first against Misawa in March, then the Kawada match, and finally against Taue in July. This led some to say that “the four pillars were raised by Hansen”, but in The Sun Rises Again, a 2003 book published for the Japanese market, Hansen claimed that he wasn’t trying to do so consciously. He was trying to protect his spot and hold them down, but they kept getting back up.[1] -------------- And now for something a little different. This doesn’t directly pertain to this narrative, but I think it’s a valuable piece of context for this era of AJPW. PRO WRESTLING NEWS Above: AJPW commentator Akira Fukuzawa interviews the Dynamite Kid in a comedic segment from an unconfirmed episode of AJPW TV. Fukuzawa’s pet segment Pro Wrestling News was a controversial staple of early-90s AJPW television. On April 18, 1989, Jumbo Tsuruta defeated Stan Hansen to unify the NWA International Heavyweight, PWF Heavyweight & NWA United National titles to create the Triple Crown Heavyweight Championship. Upon his victory, Tsuruta was interviewed in the ring by a Nippon TV presenter making his debut for AJPW television: Akira Fukuzawa. Fukuzawa would continue to make appearances in this capacity until April 1990. When longtime commentator Takao Kuramochi stepped down to work behind the scenes at Nippon TV, Fukuzawa would take his place...just as AJPW was moved to the 12:30am Sunday timeslot. Fukuzawa was an inexperienced commentator, and his early performances definitely showed it, but where Fukuzawa would shine was a segment developed after the timeslot change: “Pro Wrestling News”. The stated purpose was to communicate extratextual information such as match results, wrestler comments, and brief introductions to new foreign talent. The earliest appearance of the segment that I could find was on the July 23, 1990 episode. It’s played mostly straight, appearing to cover Yatsu’s mid-tour departure, establish the also soon-to-depart Great Kabuki as Tsuruta’s new tag partner, and briefly touch on Misawa. Even in this first go-around, though, Fukuzawa was reading their quotes in what seemed to be vocal impressions. In the next episode’s segment, though, Fukuzawa went even further. In a segment addressing Danny Spivey’s mid-tour departure, Fukuzawa went off-script and added his own comment (something along the lines of “I caused a lot of trouble for all of you. I'm fine now, I just want to get out of here!”) in an approximation of a foreign accent. In the coming months, “Pro Wrestling News” would stretch further into comedic interview segments with foreign wrestlers. On the October 14, 1990 episode, Fukuzawa asked Abdullah the Butcher for his thoughts on the company’s new tour bus. In an episode I could not find on YouTube but from which I found the header screenshots on a Japanese blog, Fukuzawa interviewed the Dynamite Kid about his attempts to learn Japanese, to which Dynamite responded with phrases in a manner that the blogger compared to actor Yusaku Matsuda. Fukuzawa’s irreverent approach was controversial. There were some fans who found it disrespectful of pro wrestling, and that disdain could be seen among both Fukuzawa’s colleagues (when once forced to host the segment in Fukuzawa’s absence, co-commentator Kenji Wakabayashi openly stated his contempt for it) and the wrestling industry itself (NJPW’s Hiroshi Hase threatened violence upon Fukuzawa[2]). However, Ichinose notes that “Pro Wrestling News” was popular with the younger audience that AJPW was catering to in the early 90s. On the first episode of 1991, in the wrestling equivalent of “if you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog”, Fukuzawa vowed that he would take a moonsault from Kobashi if the program did not draw a 10% viewership rating by the end of the year. He would eventually walk back on this due to the program having gotten a 10% rating for a segment, but they did show growth. The average rating was in the 3-4% range, but the February 10, December 8, and December 22 shows drew 6.7%, 7.0%, and 8.2% respectively. Around this time, “Pro Wrestling News” even had its own set built, although this would eventually be scrapped for a travelling approach. When the timeslot cut to thirty minutes took effect in March 1994, the segment ended with a skit. In what may have been a farcical reference to the 1960 assassination of Japan Socialist Party chairman Inejirō Asanuma, a crazed fan stabbed Fukuzawa in the chest. Fukuzawa said “I knew this day would come” as he fell to his death...before someone offscreen yelled the Japanese equivalent of "Cut!", upon which Fukuzawa broke character, got back up, and walked out of the room with the rest of the crew.

-